Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 546, May 12, 1832

"I don't wonder that that should surprise you, my dear; but he was not aware of what he was doing. It was in the dark."

"In the dark! But I could see very well who it was, though I did not know her so well as he did, and was so much farther off."

"I am afraid you are in the dark, too, a little as yet," said Lady Gayland, (tapping her gently with her fan.) "But, tell me, did you not admire the singing, though you could not understand the story."

"Why, I should, perhaps, if I had known the language; but even then they seemed to me more like birds, than men and women singing words. I like a song that I can make out every word that's said."

"The curtain then rose for the ballet; at first, Lucy was delighted with the scenery and pageantry, for the spectacle was grand and imposing. But at length the resounding plaudits announced the entrée of the perfect Taglioni. Lucy was a little astonished at her costume upon her first appearance. She was attired as a goddess, and goddesses' gowns are somewhat of the shortest, and their legs rather au naturel; but when she came to elicit universal admiration by pointing her toe, and revolving in the slow pirouette, Lucy, from the situation in which she sat was overpowered with shame at the effect; and whilst Lady Gayland, with her longnette fixed on the stage, ejaculated, 'Beautiful! inimitable!' the unpractised Lucy could not help exclaiming, 'O that is too bad! I cannot stay to see that!' and she turned her head away blushing deeply."

"Is your ladyship ill?" exclaimed Lord Stayinmore. "Castleton, I am afraid Lady Castleton feels herself indisposed."

"Would you like to go?" kindly inquired Castleton.

"O so much!" she answered.

"Are you ill, my dear?" asked Lady Gayland.

"Oh, no!" she said.

"Then you had better stay, it is so beautiful."

"Thank you, Lord Castleton is kind enough to let me go."

(They get into the carriage.)

"And how do you find yourself now, my dear Lucy?" tenderly inquired Castleton, as the carriage drove off.

"Oh, I am quite well, thank you."

"Quite well! are you? What was it, then, that was the matter with you?"

"There was nothing the matter with me, it was that woman."

"What woman? what can you mean? Did you not say that you were ill; and was not that the reason that we hurried away?"

"No! YOU said I was ill; and I did not contradict you, because you tell me that in the world, as you call it, it is not always right to give the real reason for what we do; and therefore I thought, perhaps, that though of course you wished me to come away, you liked to put it upon my being ill."

"Of course I wished you to come away! I was never more unwilling to move in all my life; and nothing but consideration for your health would have induced me to stir. Why should I have wished you to come away?"

"Why, the naked woman," stammered Lucy.

"What can you mean?"

"You couldn't surely wish me to sit by the side of those people, to see such a thing as that?"

"As to being by the side of those people, I must remind you, that it was Lady Gayland's box in which you were; and that whatever she, with her acknowledged taste and refinement, sanctions with her presence, can only be objected to by ignorance or prejudice. You have still a great deal to learn, my dear Lucy," added he, more kindly; "and nothing can be so fatal to your progress in that respect, as your attempting to lead, or to find fault, with what you do not understand."

"But surely I can understand that it is not right to do what I saw that woman do," interrupted Lucy, presuming a little more doggedly than she usually ventured to do on any subject with her husband; for this time she had been really shocked by what she had seen.

"Wrong it certainly is not, if you mean moral wrong. As to such an exhibition being becoming or not in point of manners, that depends entirely upon custom. Many things at your father's might strike me as coarseness, which made no impression upon you from habit, though much worse in my opinion than this presumed indecorum. Those things probably arose from ignorance on your parts, which might be corrected. This, on the other hand, from conventional indifference, consequent on custom, which it is not in you to correct. Depend upon it you will only get yourself laughed at, and me too, if you preach about dancers' petticoats."

"I don't want to preach to any body; and you know how much it fashes me to contend with you."

"Don't say FASHES, say distresses, or annoys, not fashes, for heaven's sake, my dear Lucy."

"Oh, dear, it was very stupid of me to forget it. That was one of the first things you taught me, and it is a many days since I said it last; but it is so strange to me to venture to differ with you, that I get confused, and don't say any thing as right as I could do. Even now I should like to ask, if modesty is a merit, whether nakedness ought to be a show; but I'll say no more, for I dare say you won't make me go there again."

"No, that will be the best way to settle it."

The plot of the Contrast is not, as the reader may perceive, one of fashionable life: it has more of the romance of nature in its composition: the characters are not the drawling bores that we find in fashionable novels, though their affected freaks are occasionally introduced to contrast with unsophisticated humility, and thus exhibit the deformities of high life. The whole work is, however, light as gossamer: we had almost said that a fly might read it through the meshes, without endangering his patience or liberty.

THE LIBRARY OF ENTERTAINING KNOWLEDGE

Maintains its rank in sober, we mean useful, literature. The volume before us contains such matter as is only to be found in large and expensive works, with a host of annotations from the journals of recent travellers and other volumes which bear upon the main subject. This part of the series, describing vegetable substances used for the food of man, is executed with considerable minuteness. A Pythagorean would gloat over its accuracy, and a vegetable diet man would become inflated with its success in establishing his eccentricities. The contents are the Corn-plants, Esculent Roots, Herbs, Spices, Tea, Coffee, &c. &c. In such a multiplicity of facts as the history of these plants must necessarily include, some misstatements may be expected. For example, the opinion that succory is superior to coffee, though supported by Drs. Howison and Duncan, is not entitled to notice. All over the continent, succory, or chicorée, is used to adulterate coffee, notwithstanding which a few scheming persons have attempted to introduce it in this country as an improvement, by selling it at four times its worth. Why say "it is sometimes considered superior to the exotic berry," and in the same page, "it is not likely to gain much esteem, where economy is not the consideration." We looked in vain for mention of the President of the Horticultural Society under Celery; though we never eat a fine head of this delicious vegetable without grateful recollection of Mr. T.A. Knight. All preachment of the economy of the Potato is judiciously omitted, though we fear to the displeasure of Sir John Sinclair; nor is there more space devoted to this overpraised root than it deserves. Truffles are not only used "like mushrooms," but for stuffing game and poultry, especially in France: who does not remember the perdrixaux truffes, of the Parisian carte. The chapter on coffee, cacao, tea, and sugar, is brief but entertaining. We may observe, by the way, that one of the obstacles to the profitable cultivation of tea in this country is our ignorance of the modes of drying, &c. as practised in China.

Another volume of the Entertaining Series, published since that just noticed, contains a selection of Criminal Trials, amongst which are those of Throckmorton and the Duke of Norfolk, for treason. They are, in the main, reprints from the State Trials, which the professional editor states to contain a large fund of instruction and entertainment. We have been deceived in the latter quality, though we must admit that in judicious hands, a volume of untiring interest might be wrought up from the State records. As they are, their dulness and prolixity are past endurance. As the present work proceeds in chronological order, it will doubtless improve in its entertaining character, since no class of literature has been more enriched by the publication of journals, diaries, &c., than historical biography, which will thus enable the editor to enliven his pages with characteristic traits of the principal actors. This has been done, to some extent, in the portion before us, and in like manner fits the volume for popular reading.

MANNERS & CUSTOMS OF ALL NATIONS

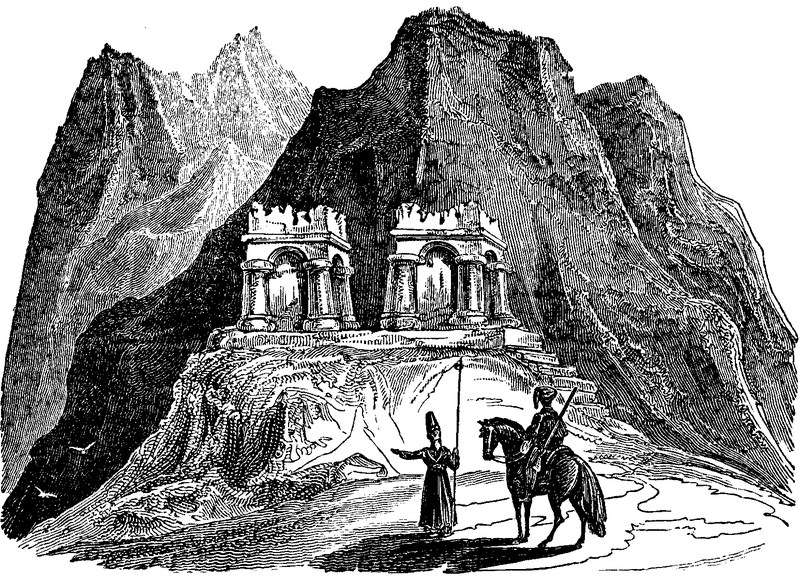

FIRE TEMPLES IN PERSIA

Persian Temple

These mystical relics are but a short journey from the celebrated ruins of Persepolis. Mr. Buckingham describes them in his usual picturesque language: "Having several villages in sight, as the sun rose, with cultivated land, flocks, trees, and water, we arrived at the foot of the mountain, which forms the northern boundary of the plain of Merdusht. The first object we saw on the west was a small rock, on which stood two fire altars of a peculiar form: their dimensions were five feet square at the base, and three at the top, and they were five feet high. There were pillars or pilasters at the corners, and arches in the sides. In the centre of each of these, near the top, was a square basin, about eight inches in diameter, and six in depth, for the reception of the fire, formerly used by the disciples of Zoroaster in their worship."

Like Pythagoras, it may be here observed, Zoroaster, the inventer of Magic, or the doctrines of the Magi, admitted no visible object of devotion except fire, which he considered as the most proper emblem of a supreme being; these doctrines seem to have been preserved by Numa, in the worship and ceremonies which he instituted in honour of Vesta. According to some of the moderns, the doctrines, laws, and regulations of Zoroaster are still extant, and they have been lately introduced in Europe, in a French translation by M. Anquetil.

Mr. Buckingham notices an existing custom, which he attributes to this reverence to fire. "Throughout all Persia, a custom prevails of giving the salute 'Salami Alaikom,' whenever the first lighted lamp or candle is brought into the room in the evening; and this is done between servants and masters as well as between equals. As this is not practised in any other Mahommedan country, it is probably a relic of the ancient reverence to fire, once so prevalent here, though the form of the salute is naturally that of the present religion."

THE NATURALIST

WHALE CHASE

A Scottish journal, the Caledonian Mercury, describes the following animated scene, which lately took place off the town of Stornoway, in the island of Lewis. An immense shoal of whales was, early in the morning, chased to the mouth of the harbour by two fishing-boats, which had met them in the offing.

"The circumstance was immediately descried from the shore, and a host of boats, amounting to 30 or 40, and armed with every species of weapon, set off to join the others in pursuit. The chase soon became one of bustle and anxiety on the part both of man and fish. The boats arranged themselves in the form of a crescent, in the fold of which the whales were collected, and where they had to encounter incessant showers of stones, splashing of oars, with frequent gashes from a harpoon or spear, while the din created by the shouts of the boats' crews and the multitude on shore, was tremendous. On more than one occasion, however, the floating phalanx was broken, and it required the greatest activity and tact ere the breach could be repaired and possession of the fugitives regained. The shore was neared by degrees, the boats advancing and retreating by turns, till at length they succeeded in driving the captive monsters on a beach opposite to the town, and within a few yards of it. The gambols of the whales were now highly diverting, and, except when a fish became unmanageable and enraged while the harpoon was fixed, or the noose of a rope pulled tight round its tail, they were not at all dangerous to be approached. In the course of a few hours the capture was complete, the shore was strewed with their dead carcases, while the sea presented a bloody and troubled aspect, giving evident proofs that it was with no small effort they were subdued. For fear of contagion, the whole fish amounting to ninety-eight, some of them very large, were immediately towed to a spot distant from the town, where they were on Thursday sold by public roup, the proceeds to be divided among the captors. An annual visit is generally paid by the whales to the Lewis coast, and besides being profitable when caught, they generally furnish a source of considerable amusement. On the present occasion, the whole inhabitants of the place, male and female, repaired to the beach, opposite to the scene of slaughter, where they evidently were delighted spectators, and occasionally gave assistance. A young sailor received a stroke from the tail of one of the largest fish, which nearly killed him."

AUDUBON

The Philadelphia journals communicate some particulars of the journey of this enterprising naturalist into E. Florida. He has discovered, shot, and drawn a new Ibis, which he has named Tantalus fuscus. In a letter, he says

"I have discovered three different new species of Heath, one bearing a yellow blossom, the two others a red and purple one;—also, a beautiful new Kalmia, and several extraordinary parasitical plants, bearing some resemblance to the pineapple plant, growing on the eastern side of the cyprus tree in swamps, about 6 or 10 feet above the water.

"During my late excursion I almost became an amphibious being—spending the most of my days in the water, and by night pitching my tent on the barren sands. Whilst I remained at Spring Garden, the alligators were yet in full life; the white-headed eagles setting; the smaller resident birds paring; and strange to say, the warblers which migrate, moving easterly every warm day, and returning every cold day, a curious circumstance, tending to illustrate certain principles in natural economy."

Six boxes of prepared skins of birds, &c. as well as a number of choice shells, seeds, roots, &c. the result of Audubon's researches, have been received in Charleston.

"In this collection there are between four and five hundred skins of Birds, several of them rare in this part of the United States—some that are never found here, and a few that have not yet been described. Of these are two of the species of Pelican (Pelicanus) not described by Wilson. The Parrot (psittacus Carolinensis); the palm warbler of Buonaparte (Silvia palmerea), and the Florida Jay, a beautiful bird without the crest, so common in that genus.

"Among the new discoveries of Audubon in Florida, we perceive a noble bird partaking of the appearance both of the Falcon and Vulture tribes, which would seem to be a connecting link between the two. His habits too, it is said, partake of his appearance, he being alternately a bird of prey, and feeding on the same food with the Vultures. This bird remains yet to be described, and will add not only a new species, but a new genus to the birds of the United States. We perceive also in Mr. Audubon's collection, a new species of Coot (Fulica).9

REMARKABLE JAY

A lady residing at Blackheath has in her possession a fine Jay, which displays instinct allied to reason and reflection in no ordinary degree. This bird is stated by a Correspondent, (A.T.) to repeat distinctly any word that may be uttered before. She can identify persons after having once seen them, and been told their names; the latter she will pronounce with surprising clearness. She has a strong affection for a goldfinch in the same apartment, the latter bird appearing to return this fondness by fluttering its wings and other demonstrations of delight. The Jay has also been seen playing with two kittens, while the old cat looked composedly on at their gambols. This bird is in beautiful plumage, and is about twenty years of age. She is well known to the residents of Blackheath and its vicinity.

ENTOMOLOGY

I have lately observed a curious fact, which I have never seen noticed in any book which has fallen in my way, viz. that it is the tail of the caterpillar which becomes the head of the butterfly. I found it hard to believe till I had convinced myself of it in a number of instances. The caterpillar weaves its web from its mouth, finishes with the head downwards, and the head, with the six front legs, are thrown off from the chrysalis, and may be found dried up, but quite distinguishable, at the bottom of the web. The butterfly comes out at the top. Is this fact generally known?—Corresp. Mag. Nat. Hist.

THE RIVER TINTO

The river Tinto rises in Sierra Morena, and empties itself into the Mediterranean, near Huelva, having the name of Tinto given it from the tinge of its waters, which are as yellow as a topaz, hardening the sand and petrifying it in a most surprising manner. If a stone happen to fall in, and rest on another, they both become in a year's time perfectly united and conglutiated. This river withers all the plants on its banks, as well as the roots of trees, which it dyes of the same hue as its waters. No kind of verdure will flourish where it reaches, nor any fish live in its stream. It kills worms in cattle, when given them to drink; but in general no animals will drink out of the river, except goats, whose flesh, nevertheless, has an excellent flavour. These singular properties continue till other rivulets run into it, and alter its nature; for when it passes by Niebla, it is not different from other rivers. It falls into the Mediterranean six leagues lower down, at the town of Huelva, where it is two leagues broad, and admits of large vessels, which may come up the river as high as San Juan del Puerto, three leagues above Huelva.—From a Correspondent.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

THE GALLEY SLAVES

About a mile distant from one of the southern barriers of Paris, a palace was built during our Henry the Sixth's brief and precarious possession of French royalty, by the Bishop of Winchester. It was known by the name of Winchester, of which, however, the French kept continually clipping and changing the consonants, until the Anglo-Saxon Winchester dwindled into the French appellation of Bicêtre. The Bishop's old palace was treated as unceremoniously as his name, being burnt in some of the civil wars. But there is this advantage in a sumptuous edifice, that its very ruins suggest the thought and supply the means of rebuilding it. Bicêtre, accordingly, reared its head, and is now a straggling mass of building, containing a mad-house, a poor-house, an hospital, and a prison.

To see it is a matter of trifling difficulty, except on one particular day—that devoted to the rivetting of the chaine. A surgeon, however, belonging to the establishment, promised to procure me admission, and on receiving his summons, I started one forenoon for Bicêtre. Mortifying news awaited my arrival. The convicts had plotted a general insurrection and escape, which was to have taken place on the preceding night. It had been discovered in time, however, and such precautions taken, as completely prevented even the attempt. The chief of these precautions appeared in half a regiment of troops, that had bivouacked all night in the square adjoining the prison, and were still some lying, some loitering about. Strict orders had been issued, that no strangers should be admitted to witness the ceremony of rivetting; and the turnkeys and gaolers, in appearance not yet recovered from the alarm of the preceding evening, refused to listen to either bribe, menace, or solicitation. It was confoundedly vexatious. Whilst expostulating with the turnkey, I caught a glimpse through a barred window of the interior court, athwart which the chains lay extended, whilst in one railed off even from this the convicts were crowded, marching round and round—precaution forbade their remaining still—and uttering from time to time such yells and imprecations as might deafen and appal a Mohawk. "I have caught a glimpse at least," thought I, as we were unceremoniously turned out.

My friend, the surgeon, bade us, however, not despair. When the man of influence arrived he hoped to prevail; and in the mean time he led us to view the other curiosities of Bicêtre. There was the well, the kitchen, the anatomical theatre. The courts were crowded with aged paupers, who each well knew that his carcass would undergo what laceration the scalpel of my friend and his comrades chose to inflict upon it. But the thought seemed not to affect them so much as it did us. Methought the business of dissecting dead subjects might have been carried on more remote from the living candidates; but I was wrong, for mystery and secrecy always beget fear.

The mad-house was another curiosity. It contains many whose brain the revolution of July, 1830, had turned. One man, a fine youth, had travelled on foot from a distant part of the kingdom, to shed his blood as a sacrifice to the memory of Napoleon. He gave his last franc to obtain admission within the pillar of the Place Vendôme, and when there opened the veins of both his arms, crying out, "I offer the blood of the brave to the manes of Napoleon." His rolling black eye was now contrasted with a face pale as death. He had lost so much blood that few hopes were entertained of his recovery.

But by far the most curious patient of the mad-house, was a young man who imagined himself to be a woman. He was handsome, but not feminine in appearance. He adored a little mirror, with which he was gratified. Rags of all colours were his delight; and he had made a precious collection. His coquetry was evident; and he answered pertinently all questions, never belying at the same time his fixed opinion, that he was endowed with a maiden's charms.

We looked over the book of reports, and found seven-eighths of the female patients to have become deranged from love; whilst, with the majority of the males, the hallucination proceeded from disappointments of ambition. Surprised, I could make out no case of a religious maniac; glad, I could discover none of a student.

We now returned to machinations for the purpose of entering the forbidden prison. Aprons were handed us, not unlike a barber's. They were surgeons' aprons, always worn by those of the establishment when on duty. Might not then the barbers' aprons be a tradition of the barber-surgeons? I refrained from asking the question in that company. The scheme was, that we should pass for Carabins—such is the nickname of French students in chirurgery—and in this quality demand admission. The Cerberus of the prison grinned at the deceit, but wearied and amused by our importunities, he actually opened the quicket and admitted us. There are two grated doors of this kind, one always locked whilst the other is opened. In an instant we were in Pandemonium.

The buildings, which surrounded and formed the courts, evidently the oldest and strongest of Bicêtre, harmonized in dinginess with the scene. At every barred window, and these were numerous, about a dozen ruffianly heads were thrust together, to regard the chains of their companions.—What a study of physiognomy! The murderer's scowl was there, by the side of the laughing countenance of the vagabond, whose shouts and jokes formed a kind of tenor to the muttered imprecations of the other. Here and there was protruded the fine, open, high-fronted head,—pale, striking, features, and dark looks, of some felon of intellect and natural superiority; whilst by his side, ignominy looked stupidly and maliciously on. A handsome little fellow at one of the grates, was dressing his hair unconsciously with most agitated fingers, evidently affected by the scene. Our question of "What are you in for?" aroused him. "False signing a billet of twenty thousand francs," replied he, with a shrug and a smile. "And he, your neighbour?" asked we cautiously, concerning one of a fine, thoughtful, philosophic, and passionate countenance. "Ha! you may ask—he gave his mistress a potion, for the purpose of merely seducing her, and it turned out to be poison—a carabin like yourselves." But these made no part of the chaine.