Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 530, January 21, 1832

THE NOVELIST

THE CONFESSION OF SERVENTIUS

From the Latin of an ancient Paduan ManuscriptBy Miss M.L. Beevor(For the Mirror.)The hours of my weary existence are fast verging to a close: already have the dreadful preparations commenced. Heavily falls the sound of the midnight bell upon my shrinking ear; upon my withered, quailing heart, it is felt in every stroke like a thunder-bolt; and the rude, reckless shout, heard, though far distant, as distinctly as the fearful throbbings of that miserable heart, tells but too eloquently that the faggots have reached their place of destination, and that the fearful pile is even now erecting. Once I believed myself one of the most courageous of men; I have beheld death in many terrible shapes, and feared it in none; but, oh! to burn,—to burn! this is a thing from which the startled spirit recoils in speechless horror, and vainly, vainly strives to wrench itself by forceful thought from the shuddering, encumbering frame! Even now, do I seem to behold the finger of scorn pointed at me;—ay,—at ME! whilst bound to the firm stake with thongs, strong as the iron bands of death, I cannot even writhe under the anguish of shame, wrath, and apprehended bodily torture! The pile is lighted,—the last words of the reckless priest have died upon mine ear, and his figure and countenance, with the myriad forms and faces, of the insulting multitude around me, are lost in suffocating volumes of uprising, dense, white smoke! The blaze enfolds me like a garment! my unspeakable tortures,—my infernal agonies have commenced!—the diabolical shouts and shrieks of the fiendish spectators—the crackling and hissing of my tender flesh—the bursting of my over swollen tendons, muscles, and arteries, with the out-gush of the crimson vital stream from every pore,—I hear,—I see,—I feel,—and in my morbid imagination, die many deaths in one! I fancied myself brave; alas! I never fancied myself—burning! But, no more; since I have taken up my pen solely to wile away these last, brief, melancholy hours, in narrating those circumstances of my past life, which shall have tended to shrivel ere long, amidst diabolical agonies, the trembling hand that records them, like a parched scroll, and to scatter the ashes of this now vigorous body, to the winds.

ROME,—the beautiful—the Eternal,—was my birthplace; and those, whom I was taught to consider as my parents, said, that the blood of its ancient heroes filled my veins. If so,—and if Servilius and Andrea, were indeed my progenitors, our family must have suffered the most amazing reverses of fortune; they were venders of fruit, lemonade, and perfumed iced waters, in the streets, but a kind-hearted pair, and for their station, well-informed.

In the clear moon-light of our Italian skies, in those soft nights, when, instead of ingloriously slumbering away the cool calm hours, all come forth who are capable of feeling the beauties and sublimities of nature, and of inhaling inspiration with the rich, odorous breeze,—in those fresh, fragrant, and impassioned hours, did Servilius and Andrea delight to lead me through ROME, and to read the Eternal City unto me, as a book; and then fell upon me, in that most sacred place, a portion of divine enthusiasm, of holy inspiration, until, in a retrospect of the thoughts, feelings, schemes, and aspirations of that infantile era, freely could I weep, and ask myself, were such things in sober earnest, ever?

It was singular, that Servilius and Andrea, never suffered me to toil; their sole care seemed to be, to bestow upon me, during their intervals of labour, all the instruction and accomplishments which their limited means allowed; and without vanity I may affirm, that my mind richly repaid them for the trouble of cultivation. I trust I was not haughty in my childhood, but when I observed other boys of my age and station, water-carriers, labourers in the vineyards, and engaged in various menial occupations from which I was exempted, the knowledge that in something I was regarded as their superior, soon forced itself upon me; I felt a distaste for the society of little unlettered, and unmannered boors, and in silence and solitude made progress in studies, which, mere matters of amusement to me, would have been hailed by many youths as tasks more severe than daily manual labour.

Servilius and Andrea associated with but few in their own rank of life; but now and then received visits from their superiors; amongst these were two, whom I shall never, never cease to remember, and to lament, and to whom, as I look backwards through the vista of five-and-thirty years, I still cannot forbear imagining that I was related by no common ties. Of this interesting pair, one was a lady, young, pale, but strikingly beautiful, and the other, a cavalier, her senior but by a very few years, handsome, noble, graceful and accomplished.

Artemisia, so was the lady called, always wore the costume of a religious house when she visited Andrea, but whether this were merely assumed for convenience, or whether she were actually one of the holy sisterhood, I had then neither the desire, nor the means of ascertaining; I only know, that she used sometimes to call me her "dear child," and seemed to vie in affection for me, with the cavalier. Serventius,—yes—the noble gentleman bore my name, for which I liked him all the better, used occasionally to meet her at the house of Servilius and Andrea; and their affection for each other struck even my childish spirit as being more than fraternal; shall I also confess, that I indulged myself in the indistinct idea—the sweet dream—that this noble, virtuous, accomplished, and beautiful pair, (whose only object in visiting our humble residence seemed to be to behold me) were my real parents, and that of Servilius and Andrea, I was only the foster-child.

One evening Serventius and Artemisia having concluded their usual repast of bread, honey, eggs and fruit, amused themselves by asking me a thousand different questions concerning the history, biography, geography, customs, religion, and arts of the ancient Romans, to all of which, my replies were, it seems, extremely satisfactory. Serventius warmly thanked Servilius and Andrea for the pains they had bestowed upon my education, and then said, turning to me:

"My son, the time is coming when we must begin to think of some profession for you; what do you desire to be?"

"A soldier," said I.

"Then ask that lady."

I flew to Artemisia, who shook her head at me. "She will not—she will not, Sir," I exclaimed, "let me be a soldier like you."

"No, my dear, I know she will not; she cannot spare you to go to the wars and get killed, so you must make up your mind never to be a soldier."

"Then," answered I proudly, "I will be a poet." Hereupon Artemisia and Serventius laughed, and informed me that the profession of a poet, if such it might be termed, was the most laborious, thankless, and ill requited of any, and that to be a poet, was in fact little better than being an honourable mendicant. The Church and the Bar were mentioned, but as I expressed a decided antipathy to them, Serventius named the medical profession.

"Yes," said I, with great glee, "I like that, and I will be a doctor;" for the bustle, importance, visiting, and gossiping of the honourable fraternity of physicians, had given me an idea that the profession itself was one of unmingled pleasure! Hapless choice! Miserable infatuation! And shall I most blame myself for selecting that which has caused my present fatal situation, or the foolish fondness which placed in the hands of a child, the decision of his future fate? But, let me proceed; the first faint glimmerings of dawn are stealing into my grated cell, and, at noon—I shudder…

Shortly after this memorable conversation, Andrea and Servilius appeared overwhelmed with affliction, and one evening brought home with them a large package, containing as I supposed, new clothes; next morning, I found that those which I had been accustomed to wear had been removed whilst I slept, and in their stead, suits of the very deepest mourning appeared. I dressed myself in one of these, and upon asking Servilius and his wife the meaning of this change, was answered by Andrea with so wild a burst of grief, and incoherent lamentation, that I durst inquire no further. After they had gone forth to their daily employment I also quitted the cottage for a stroll, and detected a woman pointing me out to her children as "a poor, little boy, who had probably lost both his parents." "That I have not," said I, sharply, "for I breakfasted with them not half an hour ago!" The woman stared at me with an expression of doubt, and muttering something that sounded extremely like "little liar," turned from me, and went her way.

(To be concluded in our next.)

SPIRIT OF DISCOVERY

ORIGIN OF PRAIRIES

The origin of prairies has occasioned much theory; it is to our mind very simple: they are caused by the Indian custom of annually burning the leaves and grass in autumn, which prevents the growth of any young trees. Time thus will form prairies; for, some of the old trees annually perishing, and there being no undergrowth to supply their place, they become thinner every year; and, as they diminish, they shade the grass less, which therefore grows more luxuriantly; and, where a strong wind carries a fire through dried grass and leaves, which cover the earth with combustible matter several feet deep, the volume of flame destroys all before it; the very animals cannot escape. We have seen it enwrap the forest upon which it was precipitated, and destroy whole acres of trees. After beginning;, the circle widens every year, until the prairies expand boundless as the ocean. Young growth follows the American settlement, since the settler keeps off those annual burnings.

American Quarterly Review.

SUTTON WASH EMBANKMENT

This is said to be one of the grandest public works ever achieved in England. It is an elevated mound of earth, with a road over, carried across an estuary of the sea situated between Lynn and Boston, and shortening the distance between the two towns more than fifteen miles. This bank has to resist, for four hours in every twelve, the weight and action of the German Ocean, preventing it from flowing over 15,000 acres of mud, which will very soon become land of the greatest fertility. In the centre the tide flows up a river, which is destined to serve as a drain to the embanked lands, and has a bridge over it of oak, with a movable centre of cast iron, for the purpose of admitting ships.

BRITISH IRON TRADE

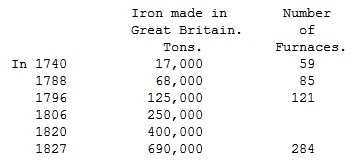

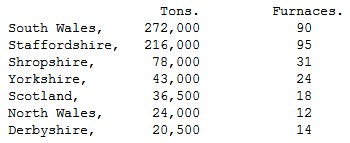

The following view of the progressive and wonderful increase of the iron-trade is extracted from the Companion to the Almanac for 1829:—

The difference iron districts in which it is made are as under, in 1827:

"About 3/10ths of this quantity is of a quality suitable for the foundry, which is all used in Great Britain and Ireland, with the exception of a small quantity exported to France and America. The other 7/10ths is made into bars, rods, sheets," &c. It will be seen that the make of the Welsh furnaces is much greater with reference to their number, than that of any other district. By a Parliamentary paper, it is stated that in 1828, of "Iron and Steel, wrought and unwrought," there were exported from Great Britain, 100,403 tons, of the declared (under real) value of 1,226,617l. In the same year 15,495 tons of bar iron was imported from abroad. We believe since 1828, the export of iron has greatly increased. Our foreign trade, however, is likely to receive a check in a short period. Both the French and Americans are beginning to manufacture extensively for themselves; a result that might naturally be anticipated. An extensive new joint-stock company has been established in the former country, one of the principal proprietors of which is Marshal Soult, and works on a great scale are forming near Montpellier. We have always thought that it was excessively injudicious to permit our machinery to be exported abroad; and it appears that the British iron masters are now constructing the machinery for these very works, where it is stated that pig iron can be made for half the price it now costs to manufacture it in this country. The exportation of machinery is continually increasing, for we find by a Parliamentary paper, the declared value in 1824 stated at 129,652l., while the machinery exported in 1829, amounts to 256,539l. Time will exhibit the policy of such proceedings.—VYVYAN.

THE GATHERER

FREDERICK I. OF PRUSSIA,

Whose chief pleasure was in the proficiency of his troops in military discipline, whenever a new soldier made his first appearance in the guards, asked him three questions. The first was, "How old are you?" the second, "How long have you been in my service?" and the third, if he received his pay and his clothing as he wished.

A young Frenchman, who had been well disciplined, offered himself to enter the guards, where he was immediately accepted, in consequence of his experience in military tactics. The young recruit did not understand the Prussian language; so that the captain informed him, that when the king saw him first on the parade, he would make the usual inquiries of him in the Prussian language, therefore he must learn to make the suitable answers, in the form of which he was instructed. As soon as the king beheld a new face in the ranks, taking a lusty piece of snuff, he went up to him, and, unluckily for the soldier, he put the second question first, and asked him how long he had been in his service. The soldier answered as he was instructed, "Twenty-one years, and please your Majesty." The king was struck with his figure, which did not announce his age to be more than the time he answered he had been in his service. "How old are you?" said the king, in surprise. "One year, please your Majesty." The king, still more surprised, said, "Either you or I must be a fool!" The soldier, taking this for the third question, relative to his pay and clothing, replied, "Both, please your Majesty." "This is the first time," said Frederick, still more surprised, "that I have been called a fool at the head of my own guards."

The soldier's stock of instruction was now exhausted; and when the monarch still pursued the design of unravelling the mystery, the soldier informed him he could speak no more German, but that he would answer him in his native tongue.

Here Frederick perceived the nature of the situation, at which he laughed very heartily, and advised the young man to apply himself to learning the language of Prussia, and mind his duty.

I.B.D.

HALF-HANGED.—ANNE GREEN

Derham, in his Physico-Theology on Respiration, says—"The story of Anne Green, executed at Oxford, December 14, 1650, is still well remembered among the seniors there. She was hanged by the neck near half an hour, some of her friends in the mean time thumping her on the breast, others hanging with all their weight upon her legs, sometimes lifting her up, and then pulling her down again with a sudden jerk, thereby the sooner to dispatch her out of her pain, as her printed account wordeth it. After she was in her coffin, being observed to breathe, a lusty fellow stamped with all his force on her breast and stomach, to put her out of her pain; but, by the assistance of Dr. Piety, Dr. Willis, Dr. Bathurst, and Dr. Clark, she was again brought to life. I myself saw her many years after, after she had (I heard) borne divers children. The particulars of her crime, execution, and restoration, see in a little pamphlet, called News from the Dead, written, as I have been informed, by Dr. Bathurst (afterwards the most vigilant and learned President of Trinity College, Oxon), and published in 1651, with verses upon the occasion."

P.T.W.

ENIGMATICAL REPLIES

A pleasant young fellow, about half-seas-over, passing through the Strand at a late hour, was accosted by a watchman, who began with all the insolence of office to file a string of interrogatories, in the hope of being handsomly paid for his trouble.

"What is your name, sir?"—"Five Shillings."

"Where do you live?"—"Out of the king's dominions."

"Where have you been?"—"Where you would have been with all your heart."

"Where are you going?"—"Where you dare not go for your ears."

The officious guardian of the night thought these answers sufficient to warrant him to take the young man to the watch-house. The next morning, on being brought before the magistrate, he told his worship, "that as to the first question, his name was Thomas Crown; with regard to the second, he lived in Little Britain; with respect to the third, he had been drinking a glass of wine with a friend; and that as to the last," said he, "I was going home to my wife." The magistrate reprimanded the watchman in severe terms, and wished Mr. Crown a good morning.—I.B.D.

SMUGGLING EXTRAORDINARY

General Anstruther, having made himself unpopular, was obliged, on his return to Scotland, to pass in disguise to his own estate; and crossing a frith, he said to the waterman, "This is a pretty boat, I fancy you sometimes smuggle with it." The fellow replied, "I never smuggled a Brigadier before."

A NOBLE COUNT

Amadeus the Ninth, Count of Savoy, being once asked where he kept his hounds, he pointed to a great number of poor people, who were seated at tables, eating and drinking, and replied, "Those are my hounds, with whom I go in chase of Heaven." When he was told that his alms would exhaust his revenues, "Take the collar of my order," said he, "sell it, and relieve my people." He was surnamed "the Happy."

P.T.W.

EPITAPHS

In Stratford Churchyard, near Salisbury.

To the memory of Elizabeth, wife of

William Brunsdon, who died Dec. 31,

1779, aged 101 years.

Freed from the sorrows, sickness, pain, and care,To which all breath-inspired clay is heir,The tend'rest mother, and the worthiest wife,Reaps the full harvest of a well-spent life.Here rest her ashes with her kindred dust—Death's only conquest o'er the favoured just:Her soul in Christ the tyrant's power defied,And the Saint triumphed when the woman died.In Amesbury Churchyard, Witts.

When sorrow weeps o'er virtue's sacred dust,Then tears become us, and our grief is just;Such cause had she to weep who gratefully paysThis last sad tribute of her love and praise,Who mourns a sister and a friend combined,Where female softness met a manly mind:Mourns, but not murmurs—sighs, but not despairs—Feels for her loss, but as a Christian bears.COLBOURNE.

FAMILIAR SCIENCE

On January 31st will be published, with many Engravings, price 5s.,

ARCANA OF SCIENCE,

AND

ANNUAL REGISTER of the USEFUL ARTS,

for 1832:

Abridged from the Transactions of Public Societies, and Scientific Journals, British and Foreign, for the past year.

*** This volume will contain all the Important Facts in the year 1831—in the

MECHANIC ARTS,

CHEMICAL SCIENCE,

ZOOLOGY,

BOTANY,

MINERALOGY,

GEOLOGY,

METEOROLOGY,

RURAL ECONOMY,

GARDENING.

DOMESTIC ECONOMY,

USEFUL AND ELEGANT ARTS,

GEOGRAPHICAL DISCOVERIES,

MISCELLANEOUS SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION.

Printing for JOHN LIMBIRD, 143, Strand; of whom may be had volumes (upon the same plan) for 1828, price 4s. 6d., 1829—30—31, price 5s. each.

1

Singapoor is derived from Sing-gah, signifying to call or touch at, bait, stop by the way; and poor, a village (generally fortified), a town, &c.—(Marsden's Malay Dictionary). It is considered at this island, or rather at this part of the island where the town is now situated (the name, however, has been given by Europeans to the whole island), there was formerly a village, inhabited principally by fishermen. The Malays, who traded from the eastward to Malacca, and others of the ports to the westward, touched at this place. Singa also signifies a lion (known by name only in the Malay countries), from which the name of the island has been (no doubt erroneously) supposed to be derived.

2

Kampong Glam, near Sincapore, has its flame derived, it is said, from Kampong, signifying a village; and Glam, the name of a particular kind of tree.

3

"He snatched lightning from heaven, and the sceptre from tyrants."

4

"Thou canst lead kings and their silly nobles."

5

"One out of many."

6

"They are called owls (striges) because they are accustomed to screech (stridere) by night."

7

Mr. Simeon's. None of our well-beloved renders, we presume, are so fresh as not to know this gentleman's name.

8

One of the sage and momentous injunctions of this pastoral charge.