Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 479, March 5, 1831

Confinement and solitude do not always kill. The Dutchman, accustomed, perhaps, to a life of indolence, existed twenty years in his cage, never enjoying the satisfaction of beholding "the human face divine," or of hearing the human voice, except when the individual entered who was charged with the duty of bringing him his provisions and cleaning his cell. Some faint rays of light, just such as enable cats and owls to mouse, found their way into the dungeon; and, by their aid, Dubourg, whom accident or the humanity of his keeper had put in possession of an old nail, and who inherited the passion of his countrymen for flowers, contrived to sculpture roses and other flowers upon the beams of his cage. Continual inaction, however, though it could not destroy life, brought on the gout, which rendered the poor wretch incapable of moving himself about from one side of the cage to the other; and he observed to his keeper, that the greatest misery he endured was inflicted by the rats, which came in droves, and gnawed away at his gouty legs, without his being able to move out of their reach or frighten them away.

Having examined the principal objects of curiosity at the mount, and learning that the tide was rising rapidly on the Grève, I descended from the fortress, and mounting my horse, set out on my return to Avranches.

My guide informed me that I had staid somewhat too long, and in fact, the sea, flowing and foaming furiously over the vast plain of sand, quickly surrounded the mount, and was at our heels in a twinkling. However, the guide sprang off with that long trot peculiar to fishermen, and was followed with great good will by the beast which had been so obstinate in the morning. We were joined in our retreat by a party of sportsmen, who appeared to have been shooting gulls upon the sands; but they could not keep up with the young fisherman, who stepped out like a Newmarket racer, and in a short time landed me safe at the Point of Pontorson, near the village of Courtils, where he resided.

By the way, we have just received Mr. St. John's Anatomy of Society, which we hope to notice in our next or subsequent number.

THE MONUMENT

Once the object of general praise, from its loftiness and beauty, and till now the subject of censure, even among Protestants, from that inscription of which the Papists always complained, was the offspring of this period, and realized one of those decorations which Wren had lavished upon his air-drawn Babylon. This lofty column was ordered by the Commons, in commemoration of the extinction of the great fire and the rebuilding of the city: it stands on the site of the old church of St. Margaret, and within a hundred feet of the spot where the conflagration began. It is of the Doric order, and rises from the pavement to the height of two hundred and two feet, containing within its shaft a spiral stair of black marble of three hundred and forty-five steps. The plinth is twenty-one feet square, and ornamented with sculpture by Cibber, representing the flames subsiding on the appearance of King Charles;—beneath his horse's feet a figure, meant to personify religious malice, crawls out vomiting fire, and above is that unjustifiable legend which called forth the indignant lines of Pope—

"Where London's column pointing to the skies,Like a tall bully, lifts his head and lies."4The shaft, deeply fluted, measures fifteen feet diameter at the base, and diminishing according to the proportion of its order, terminates in a capital, crowned with a balcony, from the centre of which rises a circular pedestal, bearing a flaming urn of gilt bronze. The various notions of the architect concerning a suitable termination, are worth relating:—"I cannot," said he, "but commend a large statue as carrying much dignity with it, and that which would be more valuable in the eyes of foreigners and strangers. It hath been proposed to cast such a one in brass of twelve feet high for a thousand pounds. I hope we may find those who will cast a figure for that money of fifteen feet high, which will suit the greatness of the pillar, and is, as I take it, the largest at this day extant. And this would undoubtedly be the noblest finishing that can be found answerable to so goodly a work in all men's judgments." The King preferred a large ball of metal gilt. A phoenix was introduced in the wooden model of the pillar, but afterwards rejected by the architect himself, "because it would be costly, not easily understood at that height, and worse understood at a distance; and lastly, dangerous by reason of the sail the spread wings would carry in the wind." A statue of Charles, fifteen feet high, on a pedestal of two hundred, would have looked small and mean; the King resisted the compliment. This work, begun in 1671, was not completed till 1677; stone was scarce, and the restoration of London and its Cathedral swallowed up the produce of the quarries. "It was at first used," says Elmes, "by the members of the Royal Society, for astronomical experiments, but was abandoned on account of its vibrations being too great for the nicety required in their observations. This occasioned a report that it was unsafe; but its scientific construction may bid defiance to the attacks of all but earthquakes for centuries."

Life of Wren.—Family LibraryG. MORLAND

H. Morland, wine merchant, brother of the painter, says, "that his brother died while his servant was holding a glass of gin (his favourite liquor) over his shoulder. And he was so prodigal at times that he had not enough to buy ultra-marine with, although a few hours before he had invited a great number of his associates to a general debauch."

GEO. ST. CLAIR

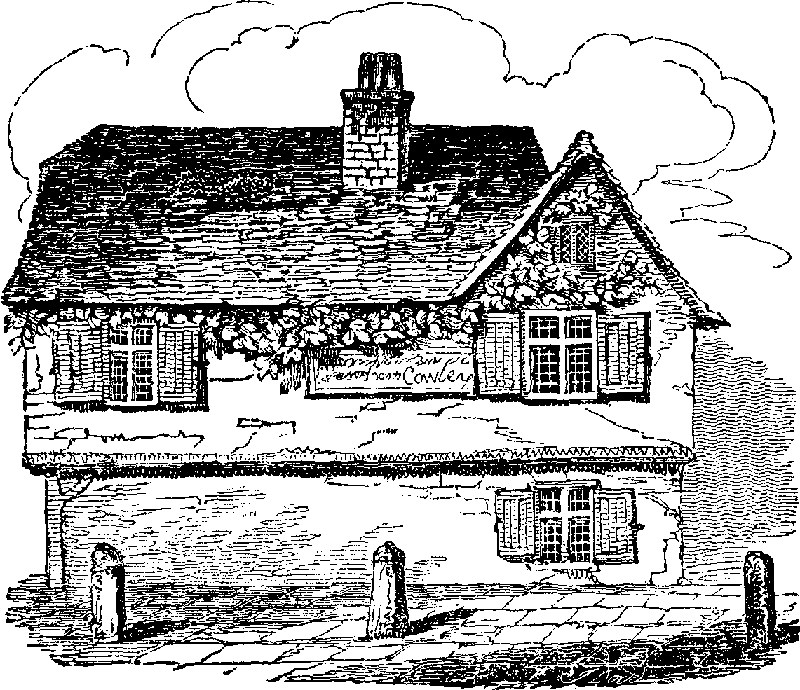

COWLEY'S HOUSE, AT CHERTSEY

Cowley retired to these premises at Chertsey, in Surrey, a few years before his death, which took place here in 1667, in his 49th year. The premises are called the Porch House, and were for many years occupied by the late Richard Clark, Esq., Chamberlain of London, who died a short time since. Mr. Clark, in honour of the Poet, took much pains to preserve the premises in their original state, kept an original portrait of Cowley, and had affixed a tablet in front, containing Cowley's Latin Epitaph on himself. In the year 1793, it was supposed that the ruinous state of the house rendered it impossible to support the building, but it was found practicable to preserve the greater part of it, to which some rooms have been added. Mr. Clark also placed a tablet in front of the building where the porch stood, with the following inscription:—"The Porch of this House, which projected ten feet into the highway, was, in the year 1792, removed for the safety and accommodation of the public.

"Here the last accents flowed from Cowley's tongue."We received the substance of this information from the venerable Mr. Clark himself, in the year 1822, about which time there appeared, in the Monthly Magazine, a view of the original premises, from a drawing by the late Mr. Samuel Ireland. The above view was taken by a Correspondent, in the summer of 1828, and represents the original portion of the mansion. Cowley's study is here pointed out, being a closet in the back part of the house, towards the garden.

How delightfully must COWLEY have passed his latter days in the rural seclusion of Chertsey! How he must have loved that earthly paradise—his garden—who could write thus for his epitaph:

From life's superfluous cares enlarg'd,His debt of human toil discharg'd,Here COWLEY lies, beneath this shed,To ev'ry worldly interest dead;With decent poverty content;His hours of ease not idly spent;To fortune's goods a foe profess'd,And, hating wealth, by all caress'd'Tis sure he's dead; for, lo! how smallA spot of earth is now his all!O! wish that earth may lightly lay,And ev'ry care be far away!Bring flow'rs, the short-liv'd roses bring,To life deceased fit offering!And sweets around the poet strow,Whilst yet with life his ashes glow.Again:

Sweet shades, adieu! here let my dust remain,Covered with flowers, and free from noise and pain;Let evergreens the turfy tomb adorn,And roseate dews (the glory of the morn)My carpet deck; then let my soul possessThe happier scenes of an eternal bliss.Then, too, the delightful chapter Of Gardens which he addressed to the virtuous John Evelyn.

We quote these few illustrations of Cowley's character from Mr. Felton's very interesting volume "on the Portraits of English Authors on Gardening."—By the way, at page 100, in a Note, Mr. Felton makes a flattering reference to one of our earliest works, which we are happy to learn has not escaped his observation.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

ORIGIN OF PAUL "PRY."

(By the Author.)The idea of the character of Paul Pry was suggested by the following anecdote, related to me several years ago, by a beloved friend:—An idle old lady, living in a narrow street, had passed so much of her time in watching the affairs of her neighbours, that she, at length, acquired the power of distinguishing the sound of every knocker within hearing. It happened that she fell ill, and was, for several days, confined to her bed. Unable to observe in person what was going on without, she stationed her maid at the window, as a substitute for the performance of that duty. But Betty soon grew weary of the occupation: she became careless in her reports—impatient and tetchy when reprimanded for her negligence.

"Betty, what are you thinking about? don't you hear a double knock at No. 9? Who is it?"

"The first-floor lodger, Ma'am."

"Betty! Betty!—I declare I must give you warning. Why don't you tell me what that knock is at No. 54!"

"Why, Lord! Ma'am, it is only the baker, with pies."

"Pies, Betty! what can they want with pies at 54?—they had pies yesterday!"

Of this very point I have availed myself. Let me add that Paul Pry was never intended as the representative of any one individual, but a class. Like the melancholy of Jaques, he is "compounded of many Simples;" and I could mention five or six who were unconscious contributors to the character.—That it should have been so often, though erroneously, supposed to have been drawn after some particular person, is, perhaps, complimentary to the general truth of the delineation.

With respect to the play, generally, I may say that it is original: it is original in structure, plot, character, and dialogue—such as they are. The only imitation I am aware of is to be found in part of the business in which Mrs. Subtle is engaged: whilst writing those scenes I had strongly in my recollection Le Vieux Celibataire. But even the little I have adopted is considerably altered and modified by the necessity of adapting it to the exigencies of a different plot.—New Monthly Magazine.

MAUREEN

The cottage is here as of old I remember,The pathway is worn as it always hath been;On the turf-piled hearth there still lives a bright ember;—But where is Maureen?The same pleasant prospect still lieth before me,The river—the mountain—the valley of green,And Heaven itself (a bright blessing!) is o'er me;—But where is Maureen?Lost! Lost!—Like a dream that hath come and departed,(Ah, why are the loved and the lost ever seen!)She has fallen—hath flown, with a lover false-hearted;—So, mourn for Maureen.And she who so loved her is slain—(the poor mother!)Struck dead in a day by a shadow unseen,And the home we once loved is the home of another,And lost is Maureen.Sweet Shannon, a moment by thee let me ponder,A moment look back at the things that have been,Then, away to the world where the ruin'd ones wander,To seek for Maureen.Pale peasant—perhaps, 'neath the frown of high Heaven,She roams the dark deserts of sorrow unseen,Unpitied—unknown; but I—I shall know evenThe ghost of Maureen.New Monthly MagazineTHE BURIAL IN THE DESERT

BY MRS HEMANSHow weeps yon gallant BandO'er him their valour could not save!For the bayonet is red with gore,And he, the beautiful and brave,Now sleeps in Egypt's sand.—WILSON.In the shadow of the PyramidOur brother's grave we made,When the battle-day was done,And the Desert's parting sunA field of death survey'd.The blood-red sky above usWas darkening into night,And the Arab watching silentlyOur sad and hurried rite.The voice of Egypt's riverCame hollow and profound,And one lone palm-tree, where we stood,Rock'd with a shivery sound:While the shadow of the PyramidHung o'er the grave we made,When the battle-day was done,And the Desert's parting sunA field of death survey'd.The fathers of our brotherWere borne to knightly tombs,With torch-light and with anthem-note,And many waving plumes:But he, the last and noblestOf that high Norman race,With a few brief words of soldier-loveWas gather'd to his place;In the shadow of the Pyramid,Where his youthful form we laid,When the battle-day was done,And the Desert's parting sunA field of death survey'd.But let him, let him slumberBy the old Egyptian wave!It is well with those who bear their fameUnsullied to the grave!When brightest names are breathed on,When loftiest fall so fast,We would not call our brother backOn dark days to be cast,From the shadow of the Pyramid,Where his noble heart we laid,When the battle-day was done,And the Desert's parting sunA field of death survey'd.Blackwood's MagazineTHE SNOW-WHITE VIRGIN

(Continued from page 125.)Her life seemed to be the same in sleep. Often at midnight, by the light of the moon shining in upon her little bed beside theirs, her parents leant over her face, diviner in dreams, and wept as she wept, her lips all the while murmuring, in broken sentences of prayer, the name of Him who died for us all. But plenteous as were his penitential tears—penitential, in the holy humbleness of her stainless spirit, over thoughts that had never left a dimming breath on its purity, yet that seemed, in those strange visitings, to be haunting her as the shadows of sins—soon were they all dried up in the lustre of her returning smiles! Waking, her voice in the kirk was the sweetest among many sweet, as all the young singers, and she the youngest far, sat together by themselves, and within the congregational music of the psalm, uplifted a silvery strain that sounded like the very spirit of the whole, even like angelic harmony blent with a mortal song. But sleeping, still more sweetly sang the "Holy Child;" and then, too, in some diviner inspiration than ever was granted to it while awake, her soul composed its own hymns, and set the simple scriptural words to its own mysterious music—the tunes she loved best gliding into one another, without once ever marring the melody, with pathetic touches interposed never heard before, and never more, to be renewed! For each dream had its own breathing, and many-visioned did then seem to be the sinless creature's sleep!

The love that was borne for her, all over the hill-region and beyond its circling clouds, was almost such as mortal creatures might be thought to feel for some existence that had visibly come from heaven! Yet all who looked on her saw that she, like themselves, was mortal; and many an eye was wet, the heart wist not why, to hear such wisdom falling from her lips; for dimly did it prognosticate, that as short as bright would be her walk from the cradle to the grave. And thus for the "Holy Child" was their love elevated by awe, and saddened by pity—and as by herself she passed pensively by their dwellings, the same eyes that smiled on her presence, on her disappearance wept!

Not in vain for others—and for herself, oh! what great gain!—for these few years on earth, did that pure spirit ponder on the word of God! Other children became pious from their delight in her piety–for she was simple as the simplest among them all, and walked with them hand in hand, nor spurned companionship with any one that was good. But all grew good by being with her–and parents had but to whisper her name—and in a moment the passionate sob was hushed–the lowering brow lighted—and the household in peace. Older hearts owned the power of the piety, so far surpassing their thoughts; and time-hardened sinners, it is said, when looking and listening to the "Holy Child," knew the errors of their ways, and returned to the right path, as at a voice from heaven.

Bright was her seventh summer—the brightest, so the aged said, that had ever, in man's memory, shone over Scotland. One long, still, sunny, blue day followed another; and in the rainless weather, though the dews kept green the hills, the song of the streams was low. But paler and paler, in sunlight and moonlight, became the sweet face that had been always pale; and the voice that had been always something mournful, breathed lower and sadder still from the too perfect whiteness of her breast. No need—no fear–to tell her thai she was about to die! Sweet whispers had sung it to her in her sleep, and waking she knew it in the look of the piteous skies. But she spoke not to her parents of death more than she had often done—and never of her own. Only she seemed to love them with a more exceeding love—and was readier, even sometimes when no one was speaking, with a few drops of tears. Sometimes she disappeared—nor, when sought for, was found in the woods about the hut. And one day that mystery was cleared; for a shepherd saw her sitting by herself on a grassy mound in a nook of the small, solitary kirkyard, miles off among the hills, so lost in reading the Bible, that shadow or sound of his feet awoke her not; and, ignorant of his presence, she knelt down and prayed—for awhile weeping bitterly—but soon comforted by a heavenly calm—that her sins might be forgiven her!

One Sabbath evening, soon after, as she was sitting beside her parents, at the door of their hut, looking first for a long while on their faces, and then for a long while on the sky, though it was not yet the stated hour of worship, she suddenly knelt down, and leaning on their knees, with hands clasped more fervently than her wont, she broke forth into tremulous singing of that hymn, which from her lips they now never heard without unendurable tears.

"The hour of my departure's come,I hear the voice that calls me home;At last, O Lord! let trouble cease,And let thy servant die in peace."They carried her fainting to her little bed, and uttered not a word to one another till she revived. The shock was sudden, but not unexpected, and they knew now that the hand of death was upon her, although her eyes soon became brighter and brighter, they thought, than they had ever been before. But forehead, cheeks, lips, neck, and breast, were, all as white, and, to the quivering hands that touched them, almost as cold, as snow. Ineffable was the bliss in those radiant eyes; but the breath of words was frozen, and that hymn was almost her last farewell. Some few words she spake, and named the hour and day she wished to be buried. Her lips could then just faintly return the kiss, and no more—a film came over the now dim blue of her eyes—the father listened for her breath—and then the mother took his place, and leaned her ear to the unbreathing mouth, long deluding herself with its lifelike smile; but a sudden darkness in the room, and a sudden stillness—most dreadful both—convinced their unbelieving hearts at last—that it was death!

All the parish, it may be said, attended her funeral—for none staid away from the kirk that Sabbath—though many a voice was unable to join in the psalm. The little grave was soon filled up, and you hardly knew that the turf had been disturbed beneath which she lay. The afternoon service consisted but of a prayer—for he who ministered, had loved her with love unspeakable—and, though an old grey-haired man, all the time he prayed he wept. In the sobbing kirk her parents were sitting, but no one looked at them—and when the congregation rose to go, there they remained sitting—and an hour afterwards, came out again into the open air—and parting with their pastor at the gate, walked away to their hut, overshadowed with the blessing of a thousand prayers!

And did her parents, soon after she was buried, die of broken hearts, or pine away disconsolately to their graves?—Think not that they, who were Christians indeed, could be guilty of such ingratitude. "The Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away—blessed be the name of the Lord!" were the first words they had spoken by that bedside; during many, many long years of weal or woe, duly every morning and night, these same blessed words did they utter when on their knees together in prayer—and many a thousand times besides, when they were apart, she in her silent hut, and he on the hill—neither of them unhappy in their solitude, though never again, perhaps, was his countenance so cheerful as of yore—and though often suddenly amidst mirth or sunshine, her eyes were seen to overflow! Happy had they been—as we mortal beings ever can be happy—during many pleasant years of wedded life before she had been born. And happy were they—on to the verge of old age—after she had here ceased to be! Their Bible had indeed been an idle book—the Bible that belonged to "the Holy Child,"—and idle all their kirk-goings with "the Holy Child," through the Sabbath-calm—had those intermediate seven years not left a power of bliss behind them triumphant over death and the grave!

Blackwood's MagazineNOTES OF A READER

FAMILIAR LAW

We cordially add our note of commendation to those already bestowed on a little Manual, entitled "Plain Advice to Landlords and Tenants, Lodging-house Keepers, and Lodgers; with a comprehensive Summary of the Law of Distress," &c. It is likewise pleasant to see "third edition" in its title-page. Accompanying we have "A Familiar Summary of the Laws respecting Masters and Servants," &c.

On looking into these little books we find much of the plain sense of law. There is no mystification by technicalities, but all the information is practical, all ready to hand, we mean mouth; so that, as Mrs. Fixture says in the farce of A Roland for an Oliver—"If there be such a thing as la' in the land," you may "ha' it." Joking apart, they are sensible books, and of good authority.

Suppose we throw ourselves back in our chair, and for a minute or two think of the good which the spread of common sense by such means as the above must produce among men: how much bile and bickering they may keep down, which in nine law-suits out of ten arise from want of "a proper understanding." The reader may say that in recommending those fire-and-water folks, landlords and tenants, and masters and servants, and those half-agreeable persons, lodging-house keepers and lodgers—to purchase such books, we advise every man to act with an attorney at his elbow. We can but reply with Swift:—

"The only fault is with mankind."CRUELTY TO ANIMALS

A very laudable work appears quarterly, entitled "The Voice of Humanity: for the communication and discussion of all subjects relative to the conduct of man towards the inferior animal creation." The number (3) before us, contains a paper on the Abolition of Slaughter-houses, and the substitution of Abattoirs, a point to which we adverted and illustrated in vol. xi. of the Mirror. The Amended Act to prevent the cruel and improper treatment of cattle, follows; and among the other articles is a Table of the Prosecutions of the Society against Cruelty to Animals, from November 1830, to January 1831, drawn up by our occasional correspondent, the benevolent Mr. Lewis Gompertz.

THE MUSE IN LIVERY

We have been somewhat amused with the piquancy and humour of the following introduction of a Notice of a volume of Poems, "by John Jones, an old servant," which has just appeared under the editorship of Mr. Southey and the Quarterly Review:—

Shakspeare has said, "What's in a name?—a rose, by any other name, would smell as sweet!" But here we have a convincing proof of the necessity of attending strictly to names, as the commonest regard to the fitting attributes of a "John Jones," would have kept the victim of such an appellation quite clear of poetry. It is next to impossible that a John Jones should be a poet;—and some kind friend should have broken the truth to the butler, before he endeavoured to share unpolished glory with uneducated bards.