Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 478, February 26, 1831

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 17, No. 478, February 26, 1831

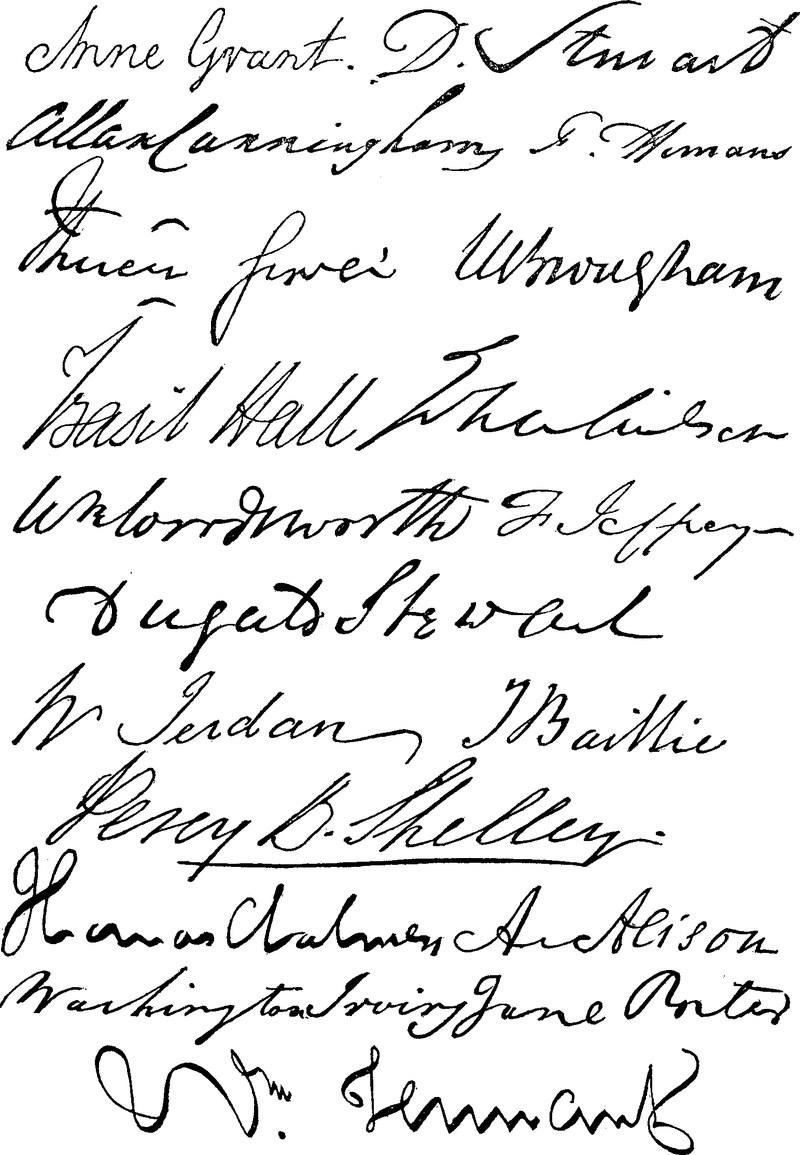

AUTOGRAPHS OF EMINENT PERSONS

AUTOGRAPHS OF EMINENT PERSONS.

AUTOGRAPHS

It is long since our pages were illustrated with such characteristic lineaments as those on the opposite page. The reader will, however, perceive that we have not entirely forgotten the quaint motto from Shenstone, in our earlier volumes—

"I want to see Mrs. Jago's handwriting, that I may judge of her temper."

Still the annexed Autographs have not been drawn from our own portfolio: they come "frae North," being selected from an engraved Plate of forty-three signatures, published with No. 28 of the Edinburgh Literary Journal, and prefixed to a pleasing chapter on "the connexion between character and handwriting"—from which we select only a few anecdotical traits.

ANNE GRANT: "We have given Mrs. Grant of Laggan's present hand, in which may be discovered a little of the instability of advancing life; but there is a well-rounded breadth and distinctness in the formation of the letters, which seems to carry along with it evidence of the clear and judicious mind of the talented authoress of 'Letters from the Mountains.'"

D. STEWART:—"General Stewart of Garth, a free, bold, military hand; his signature is taken from a letter complimenting in high terms Mr. Chambers's History of the Rebellion of 1745."

ALLAN CUNNINGHAM:—an easy flow of tasteful handwriting. "Allan Cunningham," observes the reviewer, "has raised himself like Hogg; but, instead of the plough, he has handled the chisel; and there is in his constitution an inherent love of the fine arts, which brings his thoughts into more grateful channels. We are well aware that there is a warmth and breadth of character about Cunningham which mark 'the large-soul'd Scot;' but looking forward to his forthcoming Lives of the British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, we do not conceive this to be in the least inconsistent with the easy flow of his tasteful handwriting."

F. HEMANS: "the very hand—fair, small, and beautifully feminine—in which should be embodied her gentle breathings of household love, her songs of the domestic affections, and all her lays of silvery sweetness and soft-breathing tenderness."

F. LEVESON GOWER, the distinguished translator of Goëthe's Faust.

H. BROUGHAM: "a good deal like his own style of oratory—impressive and energetic, but not very polished." We question the last; but, be this as it may, polish is only desirable so long as it does not impair truth and utility. Plain-speaking has been the best rule of conduct for public men in all ages.

BASIL HALL: the observant traveller and very ingenious writer.

JOHN WILSON (the reputed editor of Blackwood's Magazine); and beneath, F. JEFFREY (late editor of the Edinburgh Review), who took his seat in Parliament not many days since.—"These are two names which stand at the head of the periodical literature of Scotland. The periodical writer must have a ready command of his pen and a versatile genius; he must be able to pass quickly from one subject to another; and instead of devoting himself to one continuous train of thought, he must have a mind whose quick perception and comprehensive grasp enable him to grapple with a thousand. See how this applies to the handwriting of Jeffrey and of Wilson. The style of both signatures implies a quick and careless motion of the hand, as if the writer was working against time, and was much more anxious to get his ideas sent to the printer, than to cover his paper with elegant penmanship. There is an evident similarity in the fashion of the two hands—only Mr. Jeffrey, being much inferior to the Professor in point of physical size and strength, naturally enough delights in a pen with a finer point, and writes therefore a lighter and more scratchy hand than the author of 'Lights and Shadows.' It will add to the interest of Mr. Jeffrey's autograph to know that, as his hand is not at all altered, we have preferred, as a matter of curiosity, to engrave a signature of his which is twenty-three years old, being taken from a letter bearing date 1806."

W. WORDSWORTH: "a good hand, more worthy of the author of the best parts of 'The Excursion,' than of the puerilities of many of the Lyrical Ballads."

DUGALD STEWART: "a hand worthy of a moral philosopher—large, distinct, and dignified."

W. JERDAN: Editor of the Literary Gazette; free and facile as his vein of criticism, and one of the finest signatures in the page.

J. BAILLIE: "it will be perceived that it has less of the delicate feebleness of a lady's writing than any of the others. It would have been sadly against our theory had the most powerful dramatic authoress which this country has produced, written like a boarding-school girl recently in her teens. This is decidedly not the case. There is something masculine and nervous in Miss Baillie's signature; it is quite a hand in which 'De Montfort' might be written."

PERCY B. SHELLEY: Free as its author's wild and beautiful poetry; but it is not the hand of a very clear or accurate thinker.

THOMAS CHALMERS: "We know of few more striking examples of character infusing itself into hand writing, than that presented by the autograph of Dr. Chalmers. No one who has ever heard him preach, can fail to observe, that the heavy and impressive manner in which he forms his letters is precisely similar to the straining and energetic style in which he fires off his words. There is something painfully earnest and laborious in his delivery, and a similar sensation of laborious earnestness is produced by looking at his hard pressed, though manly and distinct, signature. It is in a small space, an epitome of one of his sermons."

A. ALISON; the author of "Essays on Taste," and other works of sound discrimination.

WASHINGTON IRVING; the graceful author of the "Sketch Book," free as a crayon drawing, with all its exquisite light and shade.

JANE PORTER: "a fully more masculine though less tasteful hand than Washington Irving, with whom she happens to be in juxtaposition; and the fair authoress of "Thaddeus of Warsaw," and "the Scottish Chiefs" certainly appears to have as masculine a mind as the elegant but perhaps somewhat effeminate writer of "the Sketch Book."

W. TENNANT: full of originality, and in this resembles his own 'Anster Fair.' The notion may be a fanciful one, but there seems to be a sort of quiet humour in the writing, which makes its resemblance to 'Anster Fair' still more complete. The principle upon which the letters are formed is that of making all the hair strokes heavy, and all the heavy strokes light."

HALCYON DAYS

(To the Editor.)The following account of the origin and antiquity of Halcyon Days will, I feel convinced, prove a valuable addition to that given by your intelligent correspondent P.T.W., in No. 471 of The Mirror:—

Halcyon Days, in antiquity, implied seven days before, and as many after, the winter solstice—because the halcyon laid her eggs at this time of the year, and the weather during her incubation being, as your correspondent observes, usually calm. The phrase was afterwards employed to express any season of transient prosperity, or of brief tranquillity—the septem placidae dies of human life:

The winter solstice just elapsed; and nowSilent the season, sad alcyoneBuilds near the sleeping wave her tranquil nest.Eudosia.When great Augustus made war's tempest cease,His halcyon days brought forth the arts of peace.Dryden.The halcyon built her nest on the rocks adjacent to the brink of the ocean, or, as some maintain, on the surface of the sea itself:

Alcyone compress'dSeven days sits brooding on her wat'ry nest,A wintry queen; her sire at length is kind,Calms every storm, and hushes every wind.Ovid, by Dryden.It is also said, that during the period of her incubation, she herself had absolute sway over the seas and the winds:

May halcyons smooth the waves, and calm the seas,And the rough south-east sink into a breeze;Halcyons of all the birds that haunt the main,Most lov'd and honour'd by the Nereid train.Theocritus, by Fawkes.Alcyone, or Halcyone, we are informed, was the daughter of Aeolus (king of storms and winds), and married to Ceyx, who was drowned in going to consult an oracle. The gods, it is said, apprized Alcyone, in a dream, of her husband's fate; and when she discovered, on the morrow, his body washed on shore, she precipitated herself into the watery element, and was, with her husband, metamorphosed into birds of a similar name, who, as before observed, keep the waters serene, while they build and sit on their nests.

Romford.

H.B.ARANSOMS

(To the Editor.)In a late number, you gave among the "County Collections," with which a correspondent had furnished you, the old Cornish proverb—

"Hinckston Down well wrought,Is worth London dearly bought."Possibly your correspondent was not aware that the true reading of this proverb is the following:—

"Hinckston Down well wrought,Is worth a monarch's ransom dearly bought."The lines are thus quoted by Mr. Barrington, in his elaborate work on the middle ages, and refer to the prevailing belief, that Hinckston Down is a mass of copper, and in value, therefore, an equivalent for the price set on the head of a captive sovereign. Perhaps, as some elucidation of so intricate a subject as that of the ransoming prisoners during the middle ages, the following remarks may not be deemed altogether unworthy of insertion in your pages.

Originally, the supposed right of condemning captives to death rendered the reducing of them to perpetual slavery an act of mercy on the part of the conqueror, which practice was not entirely exploded even in the fourteenth century, when Louis Hutin in a letter to Edward II. his vassal and ally, desired him to arrest his enemies, the Flemings, and make them slaves and serfs. (Mettre par deveres vous, si comme forfain à vous Sers et Esclaves à tous jours.) Rymer. Booty, however, being equally with vengeance the cause of war, men were not unwilling to accept of advantages more convenient and useful than the services of a prisoner; whose maintenance might be perhaps a burden to them, and to whose death they were indifferent. For this reason even the most sanguinary nations condescended at last to accept of ransom for their captives; and during the period between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries, fixed and general rules appear to have been established for the regulating such transactions. The principal of these seem to have been, the right of the captor to the persons of his prisoners, though in some cases the king claimed the prerogative of either restoring them to liberty, or of retaining them himself, at a price much inferior to what their original possessor had expected. On a similar principle, Henry IV. forbade the Percies to ransom their prisoners taken at Holmdown. In this case the captives consisted of the chief Scottish nobility, and the king in retaining them, had probably views of policy, which looked to objects far beyond the mere advantage of their ransom. It is mentioned by a French antiquary that the King of France had the privilege of purchasing any prisoner from his conqueror, on the payment of 10,000 livres; and as a confirmation of this, the money paid to Denis de Morbec for his captive John, King of France, by Edward III. amounted to this exact sum. The English monarch afterwards extorted the enormous ransom of three millions of gold crowns, amounting, as it has been calculated, to £1,500,000. of our present money, from his royal captive. The French author censures Edward somewhat unjustly for his share in this transaction; here as in the case of the Percies, state reasons interfered with private advantages. John yielded up to his conquerors not only the abovementioned sum, but whole towns and provinces became the property of the English nation; to these De Morbec could have no right. It was, however, notwithstanding the frequent mention in history of ransoms, still in the power of the persons in possession of a prisoner to refuse any advantage, however great, which his liberty might offer them, if dictated by motives of policy, dependant principally on his personal importance. Entius, King of Sardinia, son of Frederic II. was esteemed of such consequence to his father's affairs, that the Bolognese, to whom he became a prisoner in 1248, would accept of no price for his manumission; and he died in captivity, after a confinement of twenty-four years. Such was the conduct of Charles V. of France towards the Captal de Buche, for whose liberty he refused all the offers made to him by Edward III.

On this principle the Duke of Orleans and Comte d'Eu, were ordered by the dying injunctions of Henry V. to be retained in prison until his son should be capable of governing; nor was it until after a lapse of seventeen years, that permission was given to these noblemen to purchase their freedom.

If no state reason interfered, the conqueror made what profit he could of his prisoners. Froissart, in speaking of Poictiers, adds, that the English became very rich, in consequence of that battle, as well by ransoms as by plunder, and M. St. Palaye, in his "Mem. sur la Chevalrie," mentions that the ransom of prisoners was the principal means by which the knights of olden time supported the magnificence for which they were so remarkable. In the next century, the articles of war drawn up by Henry V. previous to his invasion of France, contain the condition, "that be it at the battle or other deeds of arms, where the prisoners are taken, he that may first have his Faye shall have him for a prisoner, and need not abide by him;" by Faye, probably the promise given by the vanquished to his captor to remain his prisoner, is understood; as the expression donner sa foi, occurs in various French historians. The value of a ransom is sometimes estimated at one year's income of a man's estate, and this opinion is supported by the custom of allowing a year's liberty to captives to procure the sum agreed upon. By the feudal law, every tenant or vassal was bound to assist his lord in captivity, by a contribution proportionate to the land he held. As, however, the amount received for prisoners is very various, personal importance had no doubt great weight in the determination of a captive's value. Bertrand du Guescelin who had no property, valued his own ransom at 100,000 livres; and Froissart, at the same period mentions the ransom of a King of Majorca, of the house of Arragon, as being exactly that sum.

(To be continued.)THE FATHERLAND. 1

(FROM THE GERMAN OF ARNDT.)(For the Mirror.)What is the German's Fatherland?On Prussia's coast, on Suabia's strand?Where blooms the vine on Rhenish shores?Where through the Belt the Baltic pours?Oh no, oh no!His Fatherland's not bounded so.What is the German's Fatherland?Bavaria's or Westphalia's strand?Where o'er his sand the Oder glides?Where Danube rolls his foaming tides?Oh no, oh no!His Fatherland's not bounded so.What is the German's Fatherland?Tell me at length that mighty land.The Swilzer's hills, or Tyrolese?Well do that land and people please,Oh no, oh no!His Fatherland's not bounded so.What is the German's Fatherland?Tell me at length the mighty land.In noble Austria's realm it lies,With honours rich and victories?Oh no, oh no!His Fatherland's not bounded so.What is the German's Fatherland?Tell me at length that mighty land,Is it what Gallic fraud of yore,From Kasier2 and the empire tore?Oh no, oh no!His Fatherland's not bounded so.What is the German's Fatherland?Tell me at length that mighty land,'Tis there where German accents raise,To God in heaven their songs of praise.That shall it beThat German is the home for thee.This is the German's Fatherland,Where vows are sworn by press of hand,Where truth in every forehead shines,Where charity the heart inclines.This shall it be,This German is the home for thee.This is the German's Fatherland,Which Gallic vices dares withstand,As enemies the wicked names,Admits the good to friendship's claims.This shall it be,This German is the home for thee.God! this for Fatherland we own,Look down on us from heaven's high throne,And give us ancient German spirit,Its truth and valour to inherit.This shall it be,The whole united Germany.HOf the author of this song some account was given in a preceding number of the Mirror. It was written on the same occasion as the Patriot's Call, when Napoleon invaded Germany, and was intended to tranquillize all petty feelings of jealousy between the separate German states. The translator believes that Messrs. Treuttel and Würtz published this song in an English dress some few years since; he has, however, never seen a copy of that work.

THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

PLUNDER OF A SPANISH DILIGENCE

(From the "Quarterly" Review, of "A Year in Spain." Unpublished.)The author takes his seat about two in the morning in the cabriolet or front part of a diligence from Tarragona, and gives many amusing particulars concerning his fellow travellers, who, one after another, all surrender themselves to slumber. Thus powerfully invited by the examples of those near him, the lieutenant catches the drowsy infection, and having nestled snugly into his corner, soon loses entirely the realities of existence "in that mysterious state which Providence has provided as a cure for every ill." In short, he is indulged with a dream, which transports him into the midst of his own family circle beyond the Atlantic; but from this comfortable and sentimental nap he is soon aroused by the sudden stopping of the diligence, and a loud clamour all about him.

There were voices without, speaking in accents of violence, and whose idiom was not of my country. I roused myself, rubbed my eyes, and directed them out of the windows. By the light of a lantern that blazed from the top of the diligence, I could discover that this part of the road was skirted by olive-trees, and that the mules, having come in contact with some obstacle to their progress, had been thrown into confusion, and stood huddled together, as if afraid to move, gazing upon each other, with pricked ears and frightened aspect. A single glance to the right-hand gave a clue to the mystery. Just beside the fore-wheel of the diligence stood a man, dressed in that wild garb of Valencia which I had seen for the first time in Amposta: his red cap, which flaunted far down his back, was in front drawn closely over his forehead; and his striped manta, instead of being rolled round him, hung unembarrassed from one shoulder. Whilst his left leg was thrown forward in preparation, a musket was levelled in his hands, along the barrel of which his eye glared fiercely upon the visage of the conductor. On the other side the scene was somewhat different. Pepe (the postilion) being awake when the interruption took place, was at once sensible of its nature. He had abandoned the reins, and jumped from his seat to the road-side, intending to escape among the trees. Unhappy youth, that he should not have accomplished his purpose! He was met by the muzzle of a musket when he had scarce touched the ground, and a third ruffian appearing at the same moment from the treacherous concealment of the very trees towards which he was flying, he was effectually taken, and brought round into the road, where he was made to stretch himself upon his face, as had already been done with the conductor.

I could now distinctly hear one of these robbers—for such they were—inquire in Spanish of the mayoral as to the number of passengers: if any were armed; whether there was any money in the diligence; and then, as a conclusion to the interrogatory, demanding La bolsa! in a more angry tone. The poor fellow meekly obeyed: he raised himself high enough to draw a large leathern purse from an inner pocket, and stretching his hand upward to deliver it, said, Toma usted, caballero, pero no me quita usted la vida! "Take it, cavalier; but do not take away my life!" The robber, however, was pitiless. Bringing a stone from a large heap, collected for the repair of the road, he fell to beating the mayoral upon the head with it. The unhappy man sent forth the most piteous cries for misericordia and piedad. He might as well have asked pity of that stone that smote him, as of the wretch who wielded it. In his agony he invoked Jesu Christo, Santiago Apostol y Martir, La Virgin del Pilar, and all those sacred names held in awful reverence by the people, and the most likely to arrest the rage of his assassin. All in vain: the murderer redoubled his blows, until, growing furious in the task, he laid his musket beside him, and worked with both hands upon his victim. The cries for pity which blows at first excited, blows at length quelled. They had gradually increased with the suffering to the most terrible shrieks; then declined into low and inarticulate moans; until a deep-drawn and agonized gasp for breath, and an occasional convulsion, alone remained to show that the vital principle had not yet departed.

It fared even worse with Pepe, though, instead of the cries for pity, which had availed the mayoral so little, he uttered nothing but low moans, that died away in the dust beneath him. One might have thought that the extreme youth of the lad would have ensured him compassion; but no such thing. The robbers were doubtless of Amposta; and, being known to him, dreaded discovery. When both the victims had been rendered insensible, there was a short pause, and a consultation in a low tone between the ruffians, who then proceeded to execute their plans. The first went round to the left side of the diligence, and, having unhooked the iron shoe and placed it under the wheel, as an additional security against escape, opened the door of the interior, and mounted on the steps. I could hear him distinctly utter a terrible threat in Spanish, and demand an ounce of gold from each of the passengers. This was answered by an expostulation from the Valencian shopkeeper, who said that they had not so much money, but what they had would be given willingly. There was then a jingling of purses, some pieces dropping on the floor in the hurry and agitation of the moment. Having remained a short time at the door of the interior, he did not come to the cabriolet, but passed at once to the rotunda. Here he used greater caution, doubtless from having seen the evening before, at Amposta, that it contained no women, but six young students, who were all stout fellows. They were made to come down, one by one, from their strong hold, deliver their money and watches, and then lie flat upon their faces in the road.

Meanwhile the second robber, after consulting with his companion, returned to the spot where the zagal Pepe lay rolling from side to side. As he went towards him, he drew a knife from the folds of his sash, and having opened it, placed one of his naked legs on either side of his victim. Pushing aside the jacket of the youth, he bent forward and dealt him repeated blows in every part of the body. The young priest, my companion, shrunk back shuddering into his corner, and hid his face within his trembling fingers; but my own eyes seemed spell-bound, for I could not withdraw them from the cruel spectacle, and my ears were more sensible than ever. Though the windows at the front and sides were still closed, I could distinctly hear each stroke of the murderous knife, as it entered its victim. It was not a blunt sound as of a weapon that meets with positive resistance, but a hissing noise, as if the household implement, made to part the bread of peace, performed unwillingly its task of treachery. This moment was the unhappiest of my life; and it struck me at the time, that if any situation could be more worthy of pity, than to die the dog's death of poor Pepe, it was to be compelled to witness his fate, without the power to aid him.

Having completed the deed to his satisfaction, this cold-blooded murderer came to the door of the cabriolet, and endeavoured to open it. He shook it violently, calling to us to assist him; but it had chanced hitherto, that we had always got out on the other side, and the young priest, who had never before been in a diligence, thought, from the circumstance, that there was but one door, and therefore answered the fellow that he must go to the other side. On the first arrival of these unwelcome visitors, I had taken a valuable watch which I wore from my waistcoat pocket, and slipped it into my boot; but when they fell to beating in the heads of our guides, I bethought me that the few dollars I carried in my purse might not satisfy them, and replaced it again in readiness to be delivered at the shortest notice. These precautions were, however, unnecessary. The third ruffian, who had continued to make the circuit of the diligence with his musket in his hand, paused a moment in the road a-head of us, and having placed his head to the ground, as if to listen, presently came and spoke in an under tone to his companions. They stood for a moment over the mayoral, and struck his head with the butts of their muskets, whilst the fellow who had before used the knife returned to make a few farewell thrusts, and in another moment they had all disappeared from around us.