Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 471, January 15, 1831

Before twelve o'clock, I left a pleasant circle, revelling in all the delights of Twelfth-cake, pam-loo, king-and-queen, and forfeits, to pack my portmanteau,

"And inly ruminate the morning's danger!"The individual who, at this time, so ably filled the important office of "Boots," at the hotel, was a character. Be it remembered that, in his youth, he had been discharged from his place for omitting to call a gentleman, who was to go by one of the morning coaches, and who, thereby, missed his journey. This misfortune made a lasting impression on the intelligent mind of Mr. Boots.

"Boots," said I in a mournful tone, "you must call me at four o'clock."

"Do'ee want to get up, zur?" inquired he, with a broad Somersetshire twang.

"Want indeed! no; but I must."

"Well, zur, I'll carl 'ee; but will 'ee get up when I do carl?"

"Why, to be sure I will."

"That be all very well to zay over-night, zur; but it bean't at all the zame thing when marnen do come. I knoa that of old, zur. Gemmen doan't like it, zur, when the time do come—that I tell 'ee."

"Like it! who imagines they should?"

"Well, zur, if you be as sure to get up as I be to carl 'ee, you'll not knoa what two minutes arter vore means in your bed. Sure as ever clock strikes, I'll have 'ee out, dang'd if I doan't! Good night, zur;" and exit Boots.

"And now I'll pack my portmanteau."

It was a bitter cold night, and my bed-room fire had gone out. Except the rush-candle, in a pierced tin box, I had nothing to cheer the gloom of a very large apartment—the walls of which (now dotted all over by the melancholy rays of the rush-light, as they struggled through the holes of the box) were of dark-brown wainscoat—but one solitary wax taper. There lay coats, trousers, linen, books, papers, dressing-materials, in dire confusion, about the room. In despair I set me down at the foot of the bed, and contemplated the chaos around me. My energies were paralyzed by the scene. Had it been to gain a kingdom, I could not have thrown a glove into the portmanteau; so, resolving to defer the packing till the morrow, I got into bed.

My slumbers were fitful—disturbed. Horrible dreams assailed me. Series of watches, each pointing to the hour of FOUR, passed slowly before me—then, time-pieces—dials, of a larger size—and at last, enormous steeple-clocks, all pointing to FOUR, FOUR, FOUR. "A change came o'er the spirit of my dream," and endless processions of watchmen moved along, each mournfully dinning in my ears, "Past four o'clock." At length I was attacked by night-mare. Methought I was an hourglass—old Father Time bestrode me—he pressed upon me with unendurable weight—fearfully and threateningly did wave his scythe above my head—he grinned at me, struck three blows, audible blows, with the handle of his scythe, on my breast, stooped his huge head, and shrieked in my ear—

"Vore o'clock, zur; I zay it be vore o'clock."

"Well, I hear you."

"But I doan't hear you. Vore o'clock, zur."

"Very well, very well, that'll do."

"Beggin' your pardon, but it woan't do, zur. 'Ee must get up—past vore zur."

"The devil take you! will you—"

"If you please, zur; but 'ee must get up. It be a good deal past vore—no use for 'ee to grumble, zur; nobody do like gettin' up at vore o'clock as can help it; but 'ee toald I to carl 'ee, and it bean't my duty to go till I hear 'ee stirrin' about the room. Good deal past vore, 'tis I assure 'ee, zur." And here he thundered away at the door; nor did he cease knocking till I was fairly up, and had shown myself to him, in order to satisfy him of the fact. "That'll do, zur; 'ee toald I to carl 'ee, and I hope I ha' carld 'ee properly."

I lit my taper at the rush-light. On opening a window-shutter I was regaled with the sight of a fog, which London itself, on one of its most perfect November days, could scarcely have excelled. A dirty, drizzling rain was falling; my heart sank within me. It was now twenty minutes past four. I was master of no more than forty disposable minutes, and, in that brief space, what had I not to do! The duties of the toilet were indispensable—the portmanteau must be packed—and, run as fast as I might, I could not get to the coach-office in less than ten minutes. Hot water was a luxury not to be procured: at that villanous hour not a human being in the house (nor, do I believe, in the universe entire), had risen—my unfortunate self, and my companion in wretchedness, poor Boots, excepted. The water in the jug was frozen; but, by dint of hammering upon it with the handle of the poker, I succeeded in enticing out about as much as would have filled a tea-cup. Two towels, which had been left wet in the room, were standing on a chair bolt upright, as stiff as the poker itself, which you might, almost as easily, have bent. The tooth-brushes were rivetted to the glass, of which (in my haste to disengage them from their strong hold) they carried away a fragment; the soap was cemented to the dish; my shaving-brush was a mass of ice. In shape more appalling Discomfort had never appeared on earth. I approached the looking-glass. Even had all the materials for the operation been tolerably thawed, it was impossible to use a razor by such a light.—"Who's there?"

"Now, if 'ee please, zur; no time to lose; only twenty-vive minutes to vive."

I lost my self-possession—I have often wondered that morning did not unsettle my mind!

There was no time for the performance of any thing like a comfortable toilet. I resolved therefore to defer it altogether till the coach should stop to breakfast.

"I'll pack my portmanteau: that must be done." In went whatever happened to come first to hand. In my haste, I had thrust in, amongst my own things, one of mine host's frozen towels. Every thing must come out again. "Who's there?"

"Now, zur; 'ee'll be too late, zur!"

"Coming!"—Every thing was now gathered together;—the portmanteau would not lock. No matter, it must be content to travel to town in a deshabille of straps. Where were my boots? In my hurry, I had packed away both pair. It was impossible to travel to London, on such a day, in slippers. Again was every thing to be undone.

"Now, zur, coach be going."

The most unpleasant part of the ceremony of hanging (scarcely excepting the closing act) must be the hourly notice given to the culprit, of the exact length of time he has yet to live. Could any circumstance have added much to the miseries of my situation, most assuredly it would have been those unfeeling reminders. "I'm coming," groaned I; "I have only to pull on my boots." They were both left-footed! Then must I open the rascally portmanteau again.

"What in the name of the—do you want now."

"Coach be gone, please zur."

"Gone! Is there a chance of my overtaking it?"

"Bless 'ee, noa, zur; not as Jem Robbins do droive. He be vive mile off be now."

"You are certain of that?"

"I warrant 'ee, zur."

At this assurance I felt a throb of joy, which was almost a compensation for all my sufferings past. "Boots," said I, "you are a kind-hearted creature, and I will give you an additional half-crown. Let the house be kept perfectly quiet, and desire the chambermaid to call me—"

"At what o'clock, zur?"

"This day three months, at the earliest."

P—.

New Monthly Magazine.* * * A welcome re-action seems to have taken place in the conduct of the New Monthly Magazine. The present is an auspicious New-year's Number. It is, moreover, embellished with a fine Bust Engraving of Sir Walter Scott, Bart.

THE PENITENT'S RETURN

By Mrs. HemansCan guilt or misery ever enter here?All! no, the spirit of domestic peace,Though calm and gentle as the brooding dove,And ever murmuring forth a quiet song,Guards, powerful as the sword of Cherubim,The hallow'd Porch. She hath a heavenly smile,That sinks into the sullen soul of vice,And wins him o'er to virtue.WILSON.My father's house once more,In its own moonlight beauty! Yet around,Something, amidst the dewy calm profound,Broods, never mark'd before.Is it the brooding night?Is it the shivery creeping on the air,That makes the home, so tranquil and so fair,O'erwhelming to my sight?All solemnized it seems,And still'd and darken'd in each time-worn hue,Since the rich clustering roses met my view,As now, by starry gleams.And this high elm, where lastI stood and linger'd—where my sisters madeOur mother's bower—I deem'd not that it castSo far and dark a shade.How spirit-like a toneSighs through yon tree! My father's place was was thereAt evening-hours, while soft winds waved his hair:Now those grey locks are gone.My soul grows faint with fear,—Even as if angel-steps had mark'd the sod.I tremble where I move—the voice of GodIs in the foliage here.Is it indeed the nightThat makes my home so awful? Faithless hearted!'Tis that from thine own bosom hath departedThe in-born gladdening light.No outward thing is changed;Only the joy of purity is fled,And, long from Nature's melodies estranged,Thou hear'st their tones with dread.Therefore, the calm abodeBy thy dark spirit is o'erhung with shade,And, therefore, in the leaves, the voice of GodMakes thy sick heart afraid.The night-flowers round that doorStill breathe pure fragrance on the untainted air;Thou, thou alone, art worthy now no moreTo pass, and rest thee there.And must I turn away?Hark, hark!—it is my mother's voice I hear,Sadder than once it seem'd—yet soft and clear—Doth she not seem to pray?My name!—I caught the sound!Oh! blessed tone of love—the deep, the mild—Mother, my mother! Now receive thy child,Take back the Lost and Found!Blackwood's Magazine.

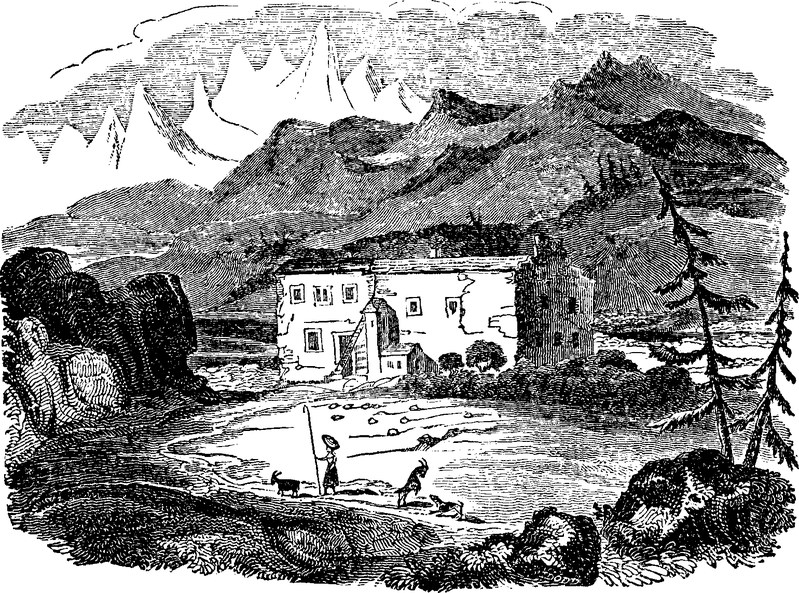

AUBERGE ON THE GRIMSEL.

AUBERGE ON THE GRIMSEL

(For the Mirror.)The Grimsel is one of the stupendous mountains of Switzerland, 5,220 feet in height, as marked on Keller's admirable map of that country. It is situated within the Canton of Berne, but bordering on that of the Valais, and not far from Uri. The auberge represented in the sketch, although not quite upon the very summit of the mountain, is almost above the limit of vegetation, and far remote from any other dwelling. Indeed, excepting a few chalets, used as summer shelter for the attendants upon the mountain cattle, but deserted in winter, there is no human habitation for many miles round; and it is one of the very few spots where the traveller has an opportunity of reposing for the night, under a comfortable roof, in so lofty a region of the atmosphere, amidst scenes of Alpine desolation—or rather, the primitive elements of Nature, "the naked bones of the earth waiting to be clothed."

The proprietor of this simple, but agreeable, auberge, is what Jeannie Deans called her father, "a man of substance," and amongst other sources of wealth possesses about three hundred goats, which contrive to pick up their living from the scanty verdure of the surrounding hills. Three times a-day they regularly assemble in front of the auberge to be milked, affording the raw material for a considerable manufacture of cheese. While we were lounging about before dinner, admiring the beautiful shapes of the rocky peaks, which even in the beginning of September were blanched with the previous night's snow, we were pleasantly surprised by the sound of a cheerful bleating, which was echoed on every side; and one after another the graceful creatures, as small and playful as our kids, popped up amongst the fragments of rocks from all quarters until the "gathering" was complete, and our meal was enlivened by the treble of their voices as the milking proceeded. When the operation was over, off they scampered again, "the hills before them were to choose"—again to return in due season with their bounteous store for the benefit of man. "This is not solitude." The milk is rich, but tastes rather too strong of the goat to be agreeable to every one at first, although probably we should soon have thought cow's milk comparatively insipid. On the day's journey we had seen some of these goats at a considerable distance from the auberge, and a young man who carried our luggage, after giving chase to several, at length caught one, and in spite of her remonstrances, milked her by main force into the cup of a pocket flask, that we might enjoy a draught of the beverage. Still holding the animal, he then filled the vessel more than once for himself, and it was amusing to see the gusto with which he drank it off. We afterwards had the milk with coffee; indeed both here and on the Righi it was "Hobson's choice," goat's milk or none at all.

This auberge has been built on the Grimsel of late years for the accommodation of travellers across the mountain passes; and it forms a convenient night's resting place in a two day's journey on foot or horseback (the only modes of threading these Alpine paths) between the valley of Meyringen and that of Urseren. It may be useful briefly to notice this route, in which the traveller will be charmed with a succession of scenery on Nature's grandest scale. After leaving Meyringen and its beautiful valley, called the Vale of Hasli, he looks down from the top of a mountain pass upon a small compact, oval-shaped valley, named, we believe Hasligrund, into which he descends, and then climbs the mountains on the opposite side. Proceeding onward, he reaches a small place, Handek, formed of a few wood chalets, and giving its name to one of the finest waterfalls in Switzerland. The accessories of the sublimest scenery give additional interest to the beauty of the fall, at which our traveller will feel inclined to linger; he should endeavour to be there about noon, when the sun irradiates the spray like dancing rainbows. The rest of the day's route is, in general, ascending, and partly across splendid sweeps of bare granite, until his eyes are gladdened with the sight of the auberge.

On the second morning he crosses the remaining summit of the mountain, and rises to cross the Furca, passing beside the Glacier of the Rhone; perhaps the finest in all the Alps, which looks like a vast torrent suddenly frozen in its course while tossing its waves into the most fantastic forms. The traveller afterwards descends into the Valley of Urseren, which extends straight before him for the distance of perhaps twelve miles, with the Reuss winding through it, and the neat town of Andermatt shining out from the opposite extremity. He passes through the singular village of Realp, where he may refresh himself with a draught of delicious Italian red wine, and afterwards arrives at the little bleak town of Hospital, situated at the foot of the St. Gothard, over which a new carriage-road into Italy has lately been made, with galleries winding up the mountain as far as the eye can reach. He may either take up his quarters for the night at Hospital, or proceed about a mile farther to Andermatt, where the road turns off at right angles, and where he may hire a car, if he wishes to go on the same evening across the romantic Devil's Bridge to Amstag, a pretty village in the bend of the splendid valley of the Reuss, whence the road leads on to Altorf and Fluellen, on the bank of the lake of the Four Cantons, the scene of the heroic exploits of William Tell.

Connecting the above sketch with one of the Fall of the Staubbach, in the Valley of Lauterbrun, in a former Mirror, (No. 403,) we may add, that the distance between the latter and Meyringen may also be performed in two days, amidst scenes, if possible, of sublimer character than the journey now described. From Lauterbrun across the Wengern Alp to the Valley of Grindenwald is the first day, the route passing in front of the Jungfrau, which throws up its magnificent ice-covered summits with more enchanting effect than the imagination can conceive. From Grindenwald, with its two fine glaciers, the path proceeds across the great Sheidech, by the baths of Rosenlaui, one of the most beautiful spots on this beautiful earth; and by the fall or rather falls, of the Rippenbach, (for there are no less than eleven in succession beneath each other,) to Meyringen.

We have thus pointed attention to a journey of four days, comprising the chief points in the Oberland, or Highlands, through this region of romantic wonders.

W.GTHE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

THE EMPEROR'S ROUT

Who does not remember the Butterfly's Ball and the Grasshopper's Feast in the halcyon days of their childhood? These toyful trifles, "light as air," doubtless suggested the Emperor's Rout. Do not start, expectant reader; this is no downfall of a royal dynasty, no burning of palaces, or muster of rebel ranks—no scamper "all on the road from Moscow"—or sauve qui peut at Waterloo; but a pleasant, little verse tale of the Emperor Moth inviting the haut ton of the Moths to a splendid rout—with notes intended as a tempting introduction to the fascinating study of entomology.

There are four Engravings: 1.—The Invitation, with the Emperor and the Empress, and the Buff-tip Moth writing the Cards.—2. The Dance, with the Sphinx Hippophaës, the Pease Blossom, the Mouse, the Seraph, Satellite, Magpie, Gold Spangle, Foresters, Cleap Wings, &c.—3. The Alarm.—4. The Death's Head Moth. These are beautifully lithographed by Gauci. Their colouring, after Nature, is delightfully executed: the finish, too, of the gold-spangle is good, and the winged brilliancy of the company are exquisite pieces of pains-taking—sparkling as they are beneath a trellis-work rotunda, garlanded with roses, and lit with a pine-pattern lustre of perfumed wax. What a close simile could we draw of life from these dozen dancing creatures in their rainbow hues—their holiday and every-day robes—flitting through life's summer, and then forgotten. Yet how fares it with us in the stream of life!

By the way, this trifle, though so prettily coloured, is in price what was once called "a trifle"—yet what kings and queens have often quarrelled for—half-a-crown.

SATAN IN SEARCH OF A WIFE

Is a little Poem, with much of the grotesque in its half-dozen Embellishments, and some tripping work in its lines. "The End," with "Who danced at the Wedding?" and the tail-piece—a devil-bantling, rocked by imps, and the cradle lit by torches—is droll enough.

Here is an invitation that promises a warm reception:

Merrily, merrily, ring the bellsFrom each Pandemonian steeple;For the Devil hath gotten his beautiful bride,And a Wedding Dinner he will provide,To feast all kinds of people.THE FAMILY CABINET ATLAS

Has reached its Ninth part, and unlike some of its periodical contemporaries, without any falling-off in its progress. The Nine Parts contain thirty-six Maps, all beautifully perspicuous. The colouring of one series is delicately executed.

MOORE'S LIFE OF BYRON. VOL. II

Letter to Mr. MurrayBologna, June 7th, 1819.

* * * * "I have been picture-gazing this morning at the famous Domenichino and Guido, both of which are superlative. I afterwards went to the beautiful cemetery of Bologna, beyond the walls, and found, besides the superb burial ground, an original of a Custode, who reminded one of the grave-digger in Hamlet. He has a collection of capuchins' skulls, labelled on the forehead, and taking down one of them, said, 'This was Brother Desiderio Berro, who died at forty—one of my best friends. I begged his head of his brethren after his decease, and they gave it me. I put it in lime, and then boiled it. Here it is, teeth and all, in excellent preservation. He was the merriest, cleverest fellow I ever knew. Wherever he went, he brought joy; and whenever any one was melancholy, the sight of him was enough to make him cheerful again. He walked so actively, you might have taken him for a dancer—he joked—he laughed—oh! he was such a Frate as I never saw before, nor ever shall again!'

"He told me that he had himself planted all the cypresses in the cemetery; that he had the greatest attachment to them and to his dead people; that since 1801 they had buried fifty-three thousand persons. In showing some older monuments, there was that of a Roman girl of twenty, with a bust by Bernini. She was a princess Barlorini, dead two centuries ago: he said that, on opening her grave, they had found her hair complete, and 'as yellow as gold.' Some of the epitaphs at Ferrar pleased me more than the more splendid monuments at Bologna; for instance—

'Martini LugiImplora pace!'Lucrezia PiciniImplora eterna quiete.'Can any thing be more full of pathos? Those few words say all that can be said or sought: the dead had had enough of life; all they wanted was rest, and this they implore! There is all the helplessness, and humble hope, and death-like prayer, that can arise from the grave—'implora pace'2 I hope whoever may survive me, and shall see me put in the foreigners' burying-ground at the Lido, within the fortress by the Adriatic, will see those two words, and no more put over me. I trust they won't think of 'pickling and bringing me home to Clod or Blunderbuss Hall.' I am sure my bones would not rest in an English grave, or my clay mix with the earth of that country. I believe the thought would drive me mad on my death-bed, could I suppose that any of my friends would be base enough to convey my carcass back to your soil.—I would not even feed your worms, if I could help it.

"So, as Shakspeare says of Mowbray, the banished Duke of Norfolk, who died at Venice, (see Richard II.) that he, after fighting

Against black Pagans, Turks, and Saracens,And toil'd with works of war, retired himselfTo Italy, and there, at Venice, gaveHis body to that pleasant country's earth,And his pure soul unto his captain, Christ,Under whose colours he had fought so long."Before I left Venice, I had returned to you your late, and Mr. Hobhouse's, sheets of Juan. Don't wait for further answers from me, but address yours to Venice, as usual. I know nothing of my own movements; I may return there in a few days, or not for some time. All this depends on circumstances. I left Mr. Hoppner very well. My daughter Allegra was well too, and is growing pretty; her hair is growing darker, and her eyes are blue. Her temper and her ways, Mr. Hoppner says, are like mine, as well as her features; she will make, in that case, a manageable young lady.

"I have never heard anything of Ada, the little Electra of my Mycenae. * * * But there will come a day of reckoning, even if I should not live to see it. I have at least, seen – shivered, who was one of my assassins. When that man was doing his worst to uproot my whole family, tree, branch, and blossoms—when, after taking my retainer, he went over to them—when he was bringing desolation on my hearth, and destruction on my household gods—did he think that, in less than three years, a natural event—a severe domestic, but an expected and common calamity—would lay his carcass in a cross-road, or stamp his name in a Verdict of Lunacy! Did he (who in his sexagenary * * *) reflect or consider what my feeling must have been, when wife, and child, and sister, and name, and fame, and country, were to be my sacrifice on his legal altar—and this at a moment when my health was declining, my fortune embarrassed, and my mind had been shaken by many kinds of disappointment—while I was yet young, and might have reformed what might be wrong in my conduct, and retrieved what was perplexing in my affairs! But he is in his grave, and * * * What a long letter I have scribbled!"

(Here is a random string of poetical gems:)—

So, we'll go no more a rovingSo late into the night,Though the heart be still as loving,And the moon be still as bright;For the sword out-wears its sheath,And the soul wears out the breast,And the heart must pause to breathe,And Love itself have rest.Though the night was made for loving,And the day returns too soon,Yet we'll go no more a rovingBy the light of the moon.Oh, talk not to me of a name great in story.The days of our youth are the days of our glory;And the myrtle and ivy of sweet two-and-twentyAre worth all your laurels, though ever so plenty.What are garlands and crowns to the brow that is wrinkled?'Tis but as a dead flower with May-dew besprinkled.Then away with all such from the head that is hoary!What care I for the wreaths that can only give glory?Oh, Fame! if I e'er took delight in thy praises,'Twas less for the sake of thy high-sounding phrases,Than to see the bright eyes of the dear One discoverShe thought that I was not unworthy to love her.There chiefly I sought thee—there only I found thee;Her glance was the best of the rays that surround thee;When it sparkled o'er aught that was bright in my story,I knew it was love, and I felt it was glory.TO THE COUNTESS OF B–You have asked for a verse,—the requestIn a rhymer 'twere strange to deny,But my Hippocrene was but my breast,And my feelings (its fountain) are dry.Were I now as I was, I had sungWhat Lawrence has painted so well;But the strain would expire on my tongue,And the theme is too soft for my shell.I am ashes where once I was fire,And the bard in my bosom is dead;What I loved I now merely admire,And my heart is as grey as my head.My Life is not dated by years—There are moments which act as a plough,And there is not a furrow appearsBut is deep in my soul as my brow.Let the young and brilliant aspireTo sing what I gaze on in vain;For sorrow has torn from my lyreThe string which was worthy the strain.