Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 372, May 30, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 13, No. 372, May 30, 1829

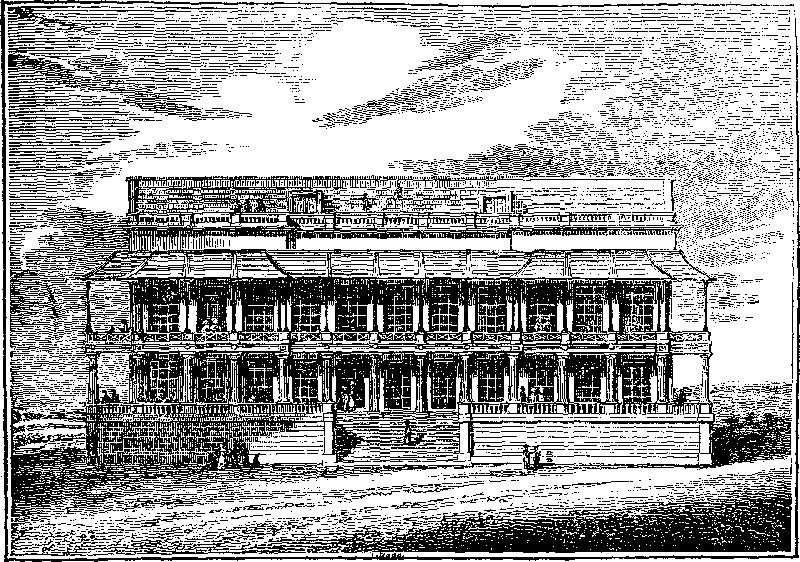

Epsom New Race Stand

We do not wish to compete with the "List of all the running horse-es, with the names, weights, and colours of the riders," although the proximity of our publication day to the commencement of Epsom Races (June 2), has induced us to select the above subject for an illustration.

The erection of the New Race Stand is the work of a company, entitled the "Epsom Grand Stand Association"—the capital £20,000, in 1,000 shares of £20 each. The speculation is patronized by the Stewards of the Jockey Club, and among the trustees is one of the county members, C.N. Pallmer, Esq. The building is now roofed in, and temporary accommodation will be provided for visitors at the ensuing Spring Races. It is after the model of the Stand at Doncaster, but is much larger, and will accommodate from 4 to 5,000 persons. The style of the architecture is Grecian.

The building is 156 feet in width, including the Terrace, and 60 feet in depth, having a portico the width, returning on each side, which is connected with a spacious terrace, raised ten feet above the level of the ground, and a magnificent flight of steps in the centre. The columns of the portico are of the Doric order, supporting a balcony, or gallery, which is to be covered by a verandah, erected on small ornamental iron pillars, placed over those below. The upper part of the Stand is to have a balustrade the whole width of the front. With reference to the interior arrangements, there are four large and well-proportioned rooms for refreshments, &c.; a spacious hall, leading through a screen of Doric columns to a large and elegant staircase of stone, and on each side of the staircase are retiring rooms of convenience for gentlemen. The entrance to this floor is from the abovementioned terrace and portico in front; and also, at the back, by an entrance which forms a direct communication through the building. The first floor consists of a splendid room, 108 feet in length, and 34 in width, divided into three compartments by ornamental columns and pilasters, supporting a richly paneled ceiling, and having a direct communication with the balcony, or gallery; and on each side of the staircase there are retiring rooms for the ladies, with the same arrangements as those below for the gentlemen. The roof will contain about 2,000 persons standing; affording, at the same time, an opportunity for every one to see the whole of the race (Derby Course) which at one time was considered doubtful.

The architect is Mr. W. Trendall; and the builder Mr. Chadwick.

By a neat plan from a survey by Mr. Mogg, the "Stand" is about ten poles from the Winning Post. It must have a most commanding view of the surrounding country–but, anon, "may we be there to see."

HISTORY OF COALS

(For the Mirror.)

Coals are found in several parts of the continent of Europe, but the principal mines are in this country. They have been discovered and wrought in Newfoundland, Cape Breton, Canada, and in some of the provinces of New England. China abounds in them, and they are well known in Tartary, and in the Island of Madagascar.

We find (says Brand) express mention of coals, used as a fuel by artificers about 2,000 years ago, in the writings of Theophrastus, the scholar of Aristotle, who, in his book on Stones, gives the substance; though some writers have not scrupled to affirm, that coal was unknown to the Ancient Britons, yet others have adduced proofs to the contrary, which seem, to carry along with them little less than conviction. The first charter for the license of digging coals, was granted by King Henry III. in the year 1239; it was there denominated sea coal; and, in 1281, Newcastle was famous for its great trade in this article; but in 1306, the use of sea coal was prohibited at London, by proclamation. Brewers, dyers, and other artificers, who had occasion for great fires, had found their account in substituting our fossil for dry wood and charcoal; but so general was the prejudice against it at that time, that the nobles and commons assembled in parliament, complained against the use thereof as a public nuisance, which was thought to corrupt the air with its smoke and stink. Shortly after this, it was the common fuel at the King's palace in London; and, in 1325, a trade was opened between France and England, in which corn was imported, and coal exported. Stowe in his "Annals" says, "within thirty years last the nice dames of London would not come into any house or roome where sea coales were burned; nor willingly eat of the meat that was either sod or roasted with sea coal fire."

Tinmouth Priory had a colliery at Elwick, which in 1330 was let at the yearly rent of five pounds; in 1530 it was let for twenty pounds a year, on condition that not more than twenty chaldron should be drawn in a day; and eight years after, at fifty pounds a year, without restriction on the quantity to be wrought. In Richard the Second's time, Newcastle coals were sold at Whitby, at three shillings and four-pence per chaldron; and in the time of Henry VIII. their price was twelvepence a chaldron in Newcastle; in London about four shillings, and in France they sold for thirteen nobles per chaldron. Queen Elizabeth obtained a lease of the manors and coal mines of Gateshead and Whickham, which she soon transferred to the Earl of Leicester. He assigned it to his secretary, Sutton, the founder of the Charter-house, who also made assignment of it to Sir W. Riddell and others, for the use of the Mayor and Burgesses of Newcastle. Duties were laid upon this article to assist in building St. Paul's Church, and fifty parish churches in London after the great fire; and in 1677, Charles II. granted to his natural son, Charles Lenox, Duke of Richmond, and his heirs, a duty of one shilling a chaldron on coals, which continued in his family till it was purchased by government in 1800. The collieries in the vicinity of Newcastle are perhaps the most valuable and extensive in Europe, and afford nearly the whole supply of the metropolis, and of those counties on the eastern coast deficient in coal strata; thus—

"The grim oreHere useless, like the miser's brighter hoard,Is from its prison brought and sent abroad,The frozen horns to cheer, to ministerTo needful sustenance and polished arts—Hence are the hungry fed, the naked clothed,The wintry damps dispell'd, and social mirthExults and glows before the blazing hearth."Iago's Edge Hill, p. 106.

P.T.WALEHOUSE SIGNS

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

Two of your correspondents have puzzled themselves in seeking the origin of the old Cat and Fiddle sign. The one has been led away by a love of etymology—the other would string the fiddle at the expense of poor puss's viscera. Now laying aside conjecture and the subtleties of language, suppose we consult plain matter of fact? It is then generally allowed that the tones of a flute resemble the human voice: those of a clarionet, the notes of a goose: and, all the world knows that a well-played violin (especially in the practice of gliding) yields sounds so inseparable from the strains of a cat, as not to be distinguished by the mere amateur of musical science.

In conformity, therefore, with this last truth, the small fiddles which Dancing-masters carry in their pockets, are at this day called kits. But our etymologist will readily perceive this to be a mere abbreviation, and that they must originally have been known as kittens.

E.D. Jun.ANACHRONISMS RESPECTING DR. JOHNSON

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

"I am corrected, sir; but hear me speak—When admiration glows with such a fireAs to o'ertop the memory, error thenMay merit mercy."—Old Play.In justice to myself and the readers of the MIRROR, I must be allowed to offer a few apologetic remarks on the almost unpardonable anachronisms which I so inadvertently suffered to occur in my communication on the subject of Dr. Johnson's Residence in Bolt Court. But when I state that the chronological metathesis occurred entirely in consequence of my referring to that most treacherous portion of human intellect, the memory; and that it is upwards of seven years since I read "Boswell's Life of Johnson," or "Johnson's Poets," it may be some mitigation of the censure I so justly deserve. Yet I may be suffered to suggest to your correspondent, who has so kindly corrected me, that my paper was more in the suppository style than he seems to have imagined; and that I did not assert that Boswell, Savage, and Johnson, met at the latter's "house in Bolt Court, and discussed subjects of polite literature." The expression used is, "We can imagine," &c. constituting a creation of the fancy rather than a positive portraiture. Certain it is that Johnson's dwelling was in the neighbourhood of Temple Bar at the time of the nocturnal perambulation alluded to; and that it was Savage (to whom he was so unaccountably attached, in spite of the "bastard's" frailties) who enticed the doctor from his bed to a midnight ramble. My primary mistake consists in transposing the date of the doctor's residence in Bolt Court, and introducing Savage at the era of Boswell's acquaintance with Johnson; whereas the wayward poet finished his miserable existence in a prison, at Bristol, 21 years prior to that event. Here I may be allowed a remark or two on the animadversion which has been heaped on Johnson for that beautiful piece of biography, "The Life of Richard Savage." It has hitherto been somewhat of a mystery that the stern critic whose strictures so severely exposed the minutest derelictions of genius in all other instances, should have adopted "the melting mood" in detailing the life of such a man as Savage; for, much as we may admire the concentrated smiles and tears of his two poems, "The Bastard," and "The Wanderer," pitying the fortunes and miseries of the author, yet his ungovernable temper and depraved propensities, which led to his embruing his hands in blood, his ingratitude to his patrons and benefactors, (but chiefly to Pope,) and his degraded misemployment of talents which might have raised him to the capital of the proud column of intellect of that day,—all conduce to petrify the tear of mingled mercy and compassion, which the misfortunes of such a being might otherwise demand. Nevertheless, as was lately observed by a respectable journal, "there must have been something good about him, or Samuel Johnson would not have loved him."

**H.DREAMS

(For the Mirror.)

We see our joyous home,Where the sapphire waters fall;The porch, with its lone gloom,The bright vines on its wall.The flow'rs, the brooks, and trees,Again are made our own,The woodlands rife with bees,And the curfew's pensive tone.Peace to the marble brow,And the ringlets tinged dark,The heart is sleeping nowIn a still and holy ark!Sleep hath clos'd the soft blue eye,And unbound the silken tressTheir dreams are of the sky,And pass'd is watchfulness.But a sleep they yet shall have,Sunn'd with no vision's glow;A sleep within the grave—When their eyes are quench'd and low!A glorious rest it is,To earth's lorn children given,Pure as the bridal kiss,To sleep—and wake in heaven! Deal. Reginald AugustineSCOTCH SONG

(For the Mirror.)

Gin Lubin shows the ring to meWhile reavin' Teviot side,And asks me wi' an earnest e'e,To be his bonny bride.At sic a time I canna tellWhat I to him might say,But as I lo'e the laddie well,I cudna tell him nae.I'd say we twa as yet are young,Wi' monie a day to spare,An' then the suit should drap my tongueThat he might press it mair.I'd gae beside the point awhile,Wi' proper laithfu' pride,By lang to partin', wi' a smile,Consent to be his bride.C. Cole.The Sketch-Book

THE LOVER STUDENT

A Leaf from the Reminiscences of a Collegian(For the Mirror.)

–—He was but a poor undergraduate; not, indeed, one of lowest grade, but still too much lacking pecuniary supplies to render him an "eligible match." Julia, too, though pretty, was portionless; and the world, which always kindly interests itself in such affairs, said, they had no business whatever to become attached to each other; but then, such attachments and the world, never did, and never will agree; and I, from fatal experience, assert that what people impertinently call "falling in love," is a thing that cannot be helped; I, at least, never could help it. The regard of Millington and Julia was of a very peculiar nature; it was a morsel of platonism, which is rather too curious to pass unrecorded; for as far as I have been able, upon the most minute investigation to ascertain, they never spoke to each other during the period of their tender acquaintance. No; they were not dumb, but lacking a mutual friend to give them an introduction; their regard for decorum and etiquette was too great to permit them to speak otherwise than with their eyes. Millington had kept three terms, when I arrived at – College, a shy and gawky freshman; we had been previously acquainted, and he, pitying perhaps my youth and inexperience, patronized his playmate, and I became his chum. For some time I was at a loss to account for sundry fluctuations in Henry's disposition and manners. He shunned society and would neither accept invitations to wine and supper parties in other men's rooms, nor give such in his own; nevertheless his person seemed to have become an object of the tenderest regard; never was he so contented as when rambling through the streets and walks, without his gown, in a new and well cut suit; whilst in order eternally to display his figure to the best advantage, he was content to endure as heavy an infliction of fines and impositions, as the heads of his college could lay upon his shoulders. He was ruined for a reading-man. About this period he also had a perfect mania for flowers; observing which, and fancying I might gratify my friend by such a mark of attention, I one day went to his rooms with a large bouquet in either hand. He was not at home; but having carelessly enough forgotten to lock his door, I commenced, con amore, (anticipating the agreeable surprise which I should afford him) to fill his vases with fresh, bright, and delicious summer flowers, in lieu of the very mummies of their race by which they were occupied. My work was in progress when Millington returned, but, oh! good heavens! the rage, the profane, diabolical, incomprehensible rage into which he burst! I shall never forget. Away went my beautiful, my fragrant flowers, into the court, and seizing upon the remnant of the mummies, as yet untouched by my sacrilegious fingers, he tossed them into a drawer, double locked it, and ordered me out of the room. Dreading a kick, I was off at his word; but had not proceeded half way down stairs, when a hand from the rear, roughly grasped mine, and a voice, in a wild and hurried manner, asked pardon for "intemperance." I should have called it madness. We were again firm allies; but I resolved to fathom, if possible, the mystery of the flowers. I now observed, with surprise, that Millington never quitted his rooms without a flower in his hand, or boutonnière; which flower, upon his return, appeared to have been either lost, or metamorphosed into, sometimes, one of another description; sometimes into a nosegay. Very strange indeed, thought I; and began to have my suspicions that in all this might be traced "fair woman's visitings." Yes, Millington must decidedly have fallen in love. He was never in chapel, never in hall, never in college, never at lectures, and never at parties; he was in love, that was certain; but with whom? He knew none of the resident gentry of –, and he was far too proud to involve himself in "an affair" with a girl of inferior rank. Many men did so; but Millington despised them for it. Accidentally I discovered that he adored Julia, the young, sweet daughter of an undoubted gentleman, who was not yet "come out." She was a lively, pretty brunette, with brownest curling hair, only fifteen; and to this day, I believe, knows not the name of her lover. From an attic window of a five storied house, this fond and beautiful girl contrived, sometimes, to shower upon the head of her devoted admirer sweet flowers, and sometimes this paragon of pairs meeting each other in the walks, silently effected an interchange of the buds and blossoms, with which they always took care to be provided. Several weeks passed thus, Henry and Julia seeing each other every day; but long vacation would arrive; and on the evening preceding his departure from –, the lovelorn student, twisting round the stem of a spicy carnation, a leaf which he had torn from his pocket book, thus conveyed, with his farewell to Julia, an intimation that he designed upon his return to college next term, to effect an introduction to her family. Julia's delight may easily be conceived. I remained in college for the vacation to read, and had shortly the pleasure of informing Millington that I should be able, upon his return, to afford him the introduction which he had so much at heart, having made the acquaintance of Julia and her family. Two months elapsed ere Millington deigned to notice my letter. His answer to it was expressed in these terms:—

"Freddy—I'm married to a proper vixen, I fancy; but to twenty thousand pounds. Ay, my boy, there it is—no doing in this world without the needful, and I'm not the ass to fight shy of such a windfall. As for Julia, hang her. By Jove, what an escape—wasn't it? Name her never again, and should she cry for me, give her a sugar plum—a kiss—a gingerbread husband, or yourself, as you please. I am not so fond of milk and water, and bread and butter, I can assure her.

"Ever truly yours,

Henry Owen Millington.

"P.S. Capital shooting hereabout—can't you slip over for a few days?"

Poor Julia! I certainly am not clear that I shall not marry her myself; but as for that scoundrel Millington, he had better take care how he comes in my way—that's all.

M.L.B.Manners & Customs of all Nations

WHITSUN ALE

(For the Mirror.)

On the Coteswold, Gloucester, is a customary meeting at Whitsuntide, vulgarly called an Ale, or Whitsun Ale, resorted to by numbers of young people. Two persons are chosen previous to the meeting, to be Lord and Lady of the Ale or Yule, who dress as suitably as they can to those characters; a large barn, or other building is fitted up with seats, &c. for the lord's hall. Here they assemble to dance and regale in the best manner their circumstances and the place will afford; each man treats his sweetheart with a ribbon or favour. The lord and lady attended by the steward, sword, purse, and mace-bearer, with their several badges of office, honour the hall with their presence; they have likewise, in their suit, a page, or train-bearer, and a jester, dressed in a parti-coloured jacket. The lord's music, consisting of a tabor and pipe, is employed to conduct the dance. Companies of morrice-dancers, attended by the jester and tabor and pipe, go about the country on Monday and Tuesday in Whitsun week, and collect sums towards defraying the expenses of the Yule. All the figures of the lord, &c. of the Yule, handsomely represented in basso-relievo, stand in the north wall of the nave of Cirencester Church, which vouches for the antiquity of the custom; and, on many of these occasions, they erect a may-pole, which denotes its rise in Druidism. The mace is made of silk, finely plaited with ribbons on the top, and filled with spices and perfumes for such of the company to smell to as desire it.

Halbert H.ANCIENT FUNERAL RITES AMONG THE GREEKS

(For the Mirror.)

The dead were ever held sacred and inviolable even amongst the most barbarous nations; to defraud them of any due respect was a greater and more unpardonable sacrilege than to spoil the temples of the gods; their memories were preserved with a religious care and reverence, and all their remains honoured with worship and adoration; hatred and envy themselves were put to silence, for it was thought a sign of a cruel and inhuman disposition to speak evil of the dead, and prosecute revenge beyond the grave. The ancient Greeks were strongly persuaded that their souls could not be admitted into the Elysian fields till their bodies were committed to the earth; therefore the honours (says Potter) paid to the dead were the greatest and most necessary; for these were looked upon as a debt so sacred, that such as neglected to discharge it were thought accursed. Those who died in foreign countries had usually their ashes brought home and interred in the sepulchres of their ancestors, or at least in some part of their native country; it being thought that the same mother which gave them life and birth, was only fit to receive their remains, and afford them a peaceful habitation after death. Whence ancient authors afford as innumerable instances of bodies conveyed, sometimes by the command of oracles, sometimes by the good-will of their friends, from foreign countries to the sepulchres of their fathers, and with great solemnity deposited there. Thus, Theseus was removed from Scyros to Athens, Orestes from Tegea, &c. Nor was this pious care limited to persons of free condition, but slaves also had some share therein; for we find (says Potter) the Athenian lawgiver commanding the magistrates, called Demarchi, under a severe penalty, to solemnize the funerals, not so much of citizens, whose friends seldom failed of paying the last honours, as of slaves, who frequently were destitute of decent burial.

Those who wasted their patrimony, forfeited their right of being buried in the sepulchres of their fathers. As soon as any person had expired, they closed his eyes. Augustus Caesar, upon the approach of his death, called for a looking-glass, and caused his hair to be combed, and his fallen cheeks decently composed. All the offices about the dead were performed by their nearest relations; nor could a greater misfortune befal any person than to want these respects. When dying, their friends and relations came close to the bed where they lay, to bid them farewell, and catch their dying words, which they never repeated without reverence. The want of opportunity to pay this compliment to Hector, furnishes Andromache with matter of lamentation, which is related in the Iliad. They kissed and embraced the dying person, so taking their last farewell; and endeavoured likewise to receive in their mouth his last breath, as fancying his soul to expire with it, and enter into their bodies. When any person died in debt at Athens, the laws of that city gave leave to creditors to seize the dead body, and deprive it of burial till payment was made; whence the corpse of Miltiades, who died in prison, being like to want the honour of burial, his son Cimon had no other means to release it, but by taking upon himself his father's debts and fetters. Sometime before interment, a piece of money was put into the corpse's mouth, which was thought to be Charon's fare for wafting the departed soul over the infernal river.

P.T.W.SINGULAR MANORIAL CUSTOM

(For the Mirror.)

The Manor of Broughton Lindsay, in Lincolnshire, is held under that of Caistor, by this strange service: viz. that annually, upon Palm Sunday, the deputy of the Lord of the Manor of Broughton, attends the church at Caistor, with a new cart whip in his hand, which he cracks thrice in the church porch; and passes with it on his shoulder up the nave into the chancel, and seats himself in the pew of the lord of the manor, where he remains until the officiating minister is about to read the second lesson; he then proceeds with his whip, to the lash of which he has in the meantime affixed a purse, which ought to contain thirty silver pennies (instead of which a single half crown is substituted,) and kneeling down before the reading desk, he holds the purse, suspended over the minister's head, all the time he is reading the lesson. After this he returns to his seat. When divine service is over, he leaves the whip and purse at the manor house.