Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 358, February 28, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 13, No. 358, February 28, 1829

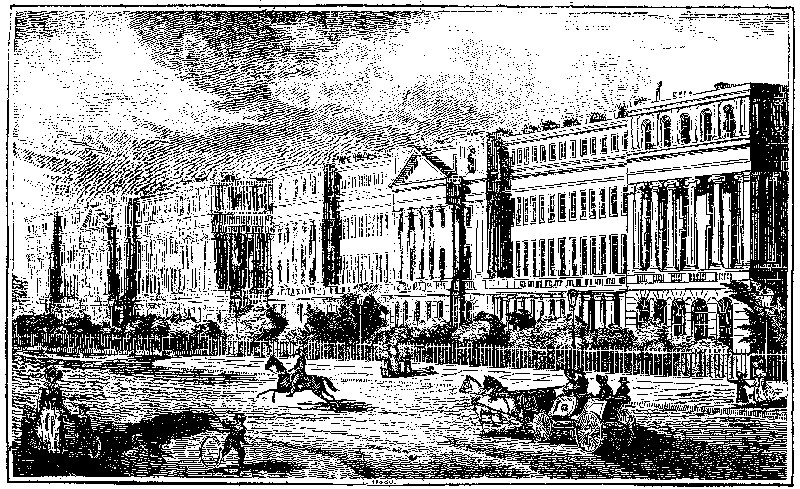

YORK TERRACE, REGENT'S PARK.

YORK TERRACE,

REGENT'S PARK

If the reader is anxious to illustrate any political position with the "signs of the times," he has only to start from Waterloo-place, (thus commencing with a glorious reminiscence,) through Regent-street and Portland-place, and make the architectural tour of the Regent's Park. Entering the park from the New Road by York Gate, one of the first objects for his admiration will be York Terrace, a splendid range of private residences, which has the appearance of an unique palace. This striking effect is produced by all the entrances being in the rear, where the vestibules are protected by large porches. All the doors and windows in the principal front represented in the engraving are uniform, and appear like a suite of princely apartments, somewhat in the style of a little Versailles. This idea is assisted by the gardens having no divisions.

The architecture of the building is Græco-Italian. It consists of an entrance or ground story, with semicircular headed windows and rusticated piers. A continued pedestal above the arches of these windows runs through the composition, divided between the columns into balustrades, in front of the windows of the principal story, to which they form handsome balconies. The elegant windows of this and the principal chamber story are of the Ilissus Ionic, and are decorated with a colonnade, completed with a well-proportioned entablature from the same beautiful order. Mr. Elmes, in his critical observations on this terrace, thinks the attic story "too irregular to accompany so chaste a composition as the Ionic, to which it forms a crown;" he likewise objects to the cornice and blocking-course, as being "also too small in proportion for the majesty of the lower order."

York Terrace is from the design of Mr. Nash, whose genius not unfrequently strays into such errors as our architectural critic has pointed out.

VALENTINE CUSTOMS

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)As some of the customs described by your correspondent W.H.H.1 are left unaccounted for, I suppose any one is at liberty to sport a few conjectures on the subject. May not, for instance, the practice of burning the "holly boy" have its origin in some of those rustic incantations described by Theocritus as the means of recalling a truant lover, or of warming a cold one; and thus translated:—

"First Delphid injured me, he raised my flame,And now I burn this bough in Delphid's name."Virgil, too, in his 8th Eclogue, alludes to the same charm:—

"Sparge molam, et fragiles incende bitumine lauros;Daphnis me malus urit, ego hanc in Daphnide laurum.""Next in the fire the bays with brimstone burn,And whilst it crackles in the sulphur, say,This I for Daphnis burn, thus Daphnis burn away."DRYDEN.The "holly bush" being made to represent the person beloved, may also be borrowed from the ancients:—

—–"Terque hæc altaria circumEffigiem duco."VIRGIL."Thrice round the altar I the image draw."The burning wax candles may be more difficult to account for, unless it refer to the custom of melting wax in order to mollify the beloved one's heart:—

"As this devoted wax melts o'er the fire,Let Myndian Delphis melt with soft desire."THEOCRITUS.—–"Hæc ut cera liquescit."—–"Sic nostro Daphnis amore."VIRGIL.For a woman to compose a garland was always considered an indication of her being in love. Aristophanes says,

"The wreathing garlands in a woman isThe usual symptom of a love-sick mind."Should the charms resorted to by lovers two thousand years ago, appear to you, even remotely, to have influenced the love rites as performed by the village men and maidens of the present day, perhaps you may deem this string of quotations worthy of a corner in your amusing miscellany.

E.

LINES

On the Sarcophagus 2 which contains the remains of Nelson in St. Paul's Cathedral (For the Mirror.)To mark th' excess of priestly pow'rTo keep in mind that gorgeous hour,Thou art no Popish monument,Altho' by Wolsey thou wer't sent,From thine own native ItalyTo tell where his proud ashes lie.To thee a nobler part is given!A prouder task design'd by heav'n!'Tis thine the sea chief's grave to shroud,Idol and wonder of the crowd!The bravest heart that ever stoodThe shock of battle on the flood!The stoutest arm that ever ledA warrior o'er the ocean's bed!Whose name long dreaded on the seaAlone secured the victory!His Britain sea-girt stood alone,Whilst all the earth was heard to moan,Beneath war's iron—iron rod,Trusting in Nelson as her god.—CYMBELINE.COINAGE OF THE ANCIENT BRITONS

(For the Mirror.)In 1749, a considerable number of gold coins were discovered on the top of Karnbre, in Cornwall, which are clearly proved to have belonged to the ancient Britons. The figures that were first stamped on the coins of all nations were those of oxen, horses, sheep, &c. It may, therefore, be concluded, that the coins of any country which have only the figures of cattle stamped on them, and perhaps of trees, representing the woods in which their cattle pastured,—were the most ancient coins of the country. Some of the gold coins found at Karnbre, and described by Dr. Borlase, are of this kind, and may be justly esteemed the most ancient of our British coins. Sovereigns soon became aware of the importance of money, and took the fabrication of it under their own direction, ordering their own heads to be impressed on one side of the coins, while the figure of some animal still continued to be stamped on the other. Of this kind are some of the Karnbre coins, with a royal head on one side, and a horse on the other. When the knowledge and use of letters were once introduced into any country, it would not be long before they appeared on its coins, expressing the names of the princes whose heads were stamped on them. This was a very great improvement in the art of coining, and gave an additional value to the money, by preserving the memories of princes, and giving light to history. Our British ancestors were acquainted with this improvement before they were subdued by the Romans, as several coins of ancient Britain have very plain and perfect inscriptions, and on that account merit particular attention.

INA.

ANIMAL FOOD

(For the Mirror.)It is generally allowed, that a profusion of animal food has a tendency to vitiate and debase the nature and dispositions of men; notwithstanding, the lovers of flesh urge the names of many of the most eminent in literature and science, in opposition to this assertion.

Plutarch attributed the stupidity of his countrymen, the Boeotians, to the profusion of animal food which they consumed, and even now, our lovely, soup drinking, coffee sipping friends on the continent, attribute the saturnine, melancholy, and bearish dispositions of John Bull, to his partiality for,

"The famous roast-beef of Old England."A facetious, philosophical, friend of mine, lately amused me with some remarks, on the nature and properties of different kinds of food. "We know," said he, "that one herb produces this effect, and another that; that different species and varieties of plants have different virtues; and, why may we not infer that the same rule extends to animated nature; that our fish, flesh, and fowl, not only serve as nutriment, but that each kind possesses peculiar and individual properties."

This will account for the piggish habits and propensities so conspicuous in the inhabitants of certain places in England, and whose partiality for swine's flesh, is proverbial. The sheepish manners of our students and school-boys, may also be attributed to the mutton so generally alloted to them. I might continue my observations, ad infinitum. I might say, that the wisdom of the goose was discoverable in—whose love of that, "most abused of God's creatures," is well known: and that the sea-side predilections of a certain Bart., of festive notoriety, were occasioned by his partiality for turtle.

QUÆSITOR.

WHITEHALL.

MARRIAGE OF ANNE BOLEYN

(For the Mirror)The extraordinary revolution which took place in our religious institutions in the time of Henry VIII., has rendered his reign one of the most important in the annals of ecclesiastical history. For the great changes at that glorious æra, the reformation, when the clouds of ignorance and superstition were dispelled, we are principally indebted to the beauteous, but unfortunate Anne Boleyn, whose influence with the haughty monarch, was the chief cause of the abolition of the papal supremacy in England; one of the greatest blessings ever bestowed by a monarch on his country. Intimately associated with, and the principal scene of these important events, was the ancient palace of Whitehall,3 which Henry, into whose possession it came on the premunire of Wolsey, considerably enlarged and beautified, changing its name from that of York Place, to the one by which it is still designated.

In this building, an event, the most important, in its consequences, recorded in the history of any country, took place,—the marriage of Anne Boleyn, who had been created Countess of Pembroke, with the "stern Harry." The precise period of these nuptials, owing to the secrecy with which they were performed, is involved in considerable obscurity, and has given rise to innumerable controversies among historians; the question not being even to this hour satisfactorily decided as to whether they were solemnized in the month of November, 1532, or in that of January, 1533. Hall,4 Holinshed,5 and Grafton, whose authority several of our more modern historians6 have followed, place it on the 14th of November, 1532, the Feast Day of St. Erkenwald; but Stow7 informs us, that it was celebrated on the 25th of January 1533; and his assertion bears considerable weight, being corroborated by a letter from Archbishop Cranmer, dated "the xvij daye of June," 1533, from his "manor of Croydon," to Hawkyns, the embassador at the emperor's court. In this letter the prelate says, "she was marid muche about St. Paules daye last, as the condicion thereof dothe well appere by reason she ys now sumwhat bygg with chylde."8 This statement, coming as it does from so authentic a source, and coinciding with the accounts of Stow, Wyatt,9 and Godwin10 may, we think, be regarded as the most correct. Her marriage was not made known until the following Easter, when it was publicly proclaimed, and preparations made for her coronation, which was conducted with extraordinary magnificence in Whitsuntide. Her becoming pregnant soon after her marriage "gave great satisfaction to the king, and was regarded by the people as a strong proof of the queen's former modesty and virtue."11 This latter circumstance, however, has not met with that consideration among historians which it appears to merit; for we must remember that Elizabeth was born on the 7th of the following September, an event, which would perhaps rather tend to confirm the opinion of Hall, in contradiction to that of Stow, if, indeed, Anne had been proof against the advances of Henry, previous to their marriage, which some writers have doubted.

Lingard, whose History is now in the course of publication, intimates that the ceremony was performed "in a garret, at the western end of the palace of Whitehall;"12 this, however, when we consider the haughty character of Henry, is totally improbable, and rests entirely on the authority of one solitary manuscript. There is no reason, however, to doubt but that they were married in some apartment in that palace, and most probably in the king's private closet.13 Dr. Rowland Lee, one of the royal chaplains, and afterwards Bishop of Coventry officiated, in the presence only of the Duke of Norfolk, uncle to the Lady Anne, and her father, mother, and brother. Lord Herbert,14 whose authority has been quoted by Hume, says, that Cranmer was also present, but this is undoubtedly an error, as that prelate had only just then returned from Germany, and was not informed of the circumstance until two weeks afterwards, as appears from the following passage in his letter to Hawkyns, before quoted:—"Yt hath bin reported thorowte a greate parte of the realme that I married her; which was playnly false, for I myself knew not thereof a fortenyght after it was donne."

It may not, perhaps, prove uninteresting to our readers, or quite irrelevant to the subject, to close this brief account of the marriage of Anne Boleyn, with the copy of a letter from that queen to "Squire Josselin, upon ye birth of Q. Elizabth," preserved among the manuscripts in the British Museum.15

"By the Queen—Trusty and well beloved wee greet you well. And whereas it hath pleased ye goodness of Almighty God of his infinite mercy and grace to send unto vs at this tyme good speed in ye deliverance and bringing forth of a Princess to ye great joye and inward comfort of my lord. Us, and of all his good and loving subjects of this his realme ffor ye which his inestimable beneuolence soe shewed unto vs. We have noe little cause to give high thankes, laude and praysing unto our said Maker, like as we doe most lowly, humbly, and wth all ye inward desire of our heart. And inasmuch as wee undoubtedly trust yt this our good is to you great pleasure, comfort, and consolacion; wee therefore by these our Lrs aduertise you thereof, desiring and heartily praying you to give wth vs unto Almighty God, high thankes, glory, laud, and praising, and to pray for ye good health, prosperity, and continuall preservation of ye sd Princess accordingly. Yeoven under our Signett at my Lds Manner of Greenwch,16 ye 7th day of September, in ye 25th yeare of my said Lds raigne, An. Dno. 1533."

S.I.B.

Memorable Days

COLLOP MONDAY

Collop Monday is the day before Shrove Tuesday, and in many parts is made a day of great feasting on account of the approaching Lent. It is so called, because it was the last day allowed for eating animal food before Lent; and our ancestors cut up their fresh meat into collops, or steaks, for salting or hanging up until Lent was over; and even now in many places it is still a custom to have eggs and collops, or slices of bacon, for dinner on this day.

In Westmoreland, and particularly at Brough, where I have witnessed it many times, the good people kill a great many pigs about a week or two previous to Lent, which have been carefully fattened up for the occasion. The good housewife is busily occupied in salting the flitches and hams to hang up in the "pantry," and in cutting the fattest parts of the pig for collops on this day. The most luscious cuts are baked in a pot in an oven, and the fat poured out into a bladder, as it runs out of the meat, for hog's-lard. When all the lard has been drained off, the remains (which are called cracklings, being then baked quite crisp) resemble the crackling on a leg of pork, are eaten with potatoes, and from the quantity of salt previously added to them, to preserve the lard, are unpalatable to many mouths. The rough farmers' men, however, devour them as a savoury dish, and every time "lard" is being made, cracklings are served up for the servants' dinner. Indeed, even the more respectable classes partake of this dish.

PIG-FRY—This is a Collop Monday dish, and is a necessary appendage to "cracklings." It consists of the fattest parts of the entrails of the pig, broiled in an oven. Numerous herbs, spices, &c. are added to it; and upon the whole, it is a more sightly "course" at table than fat cracklings. Sometimes the good wife indulges her house with a pancake, as an assurance that she has not forgotten to provide for Shrove Tuesday. The servants are also treated with "a drop of something good" on this occasion; and are allowed (if they have nothing of importance to require their immediate attention) to spend the afternoon in conviviality.

AVVER BREAD.—During Lent, in the same county, a great quantity of bread, called avver bread, is made. It is of oats, leavened and kneaded into a large, thin, round cake, which is placed upon a "girdle"17 over the fire. The bread is about the thickness of a "lady's" slice of bread and butter.

I am totally unable to give a definition of the word avver, and should feel much gratified by any correspondent's elucidation. I think P.T.W. may possibly assist me on this point; and if so, I shall be much obliged. There is an evident corruption in it. I have sometimes thought that avver means oaten, although I have no other authority than from knowing the strange pronunciation given to other words.

W.H.H.

The Contemporary Traveller

DESCRIPTION OF MEKKA

Mekka maybe styled a handsome town; its streets are in general broader than those of eastern cities; the houses lofty, and built of stone; and the numerous windows that face the streets give them a more lively and European aspect than those of Egypt or Syria, where the houses present but few windows towards the exterior. Mekka (like Djidda) contains many houses three stories high; few at Mekka are white-washed; but the dark grey colour of the stone is much preferable to the glaring white that offends the eye in Djidda. In most towns of the Levant the narrowness of a street contributes to its coolness; and in countries where wheel-carriages are not used, a space that allows two loaded camels to pass each other is deemed sufficient. At Mekka, however, it was necessary to leave the passages wide, for the innumerable visiters who here crowd together; and it is in the houses adapted for the reception of pilgrims and other sojourners, that the windows are so contrived as to command a view of the streets.

The city is open on every side; but the neighbouring mountains, if properly defended, would form a barrier of considerable strength against an enemy. In former times it had three walls to protect its extremities; one was built across the valley, at the street of Mala; another at the quarter of Shebeyka; and the third at the valley opening into the Mesfale. These walls were repaired in A.H. 816 and 828, and in a century after some traces of them still remained.

The only public place in the body of the town is the ample square of the great mosque; no trees or gardens cheer the eye; and the scene is enlivened only during the Hadj by the great number of well stored shops which are found in every quarter. Except four or five large houses belonging to the Sherif, two medreses or colleges (now converted into corn magazines,) and the mosque, with some buildings and schools attached to it, Mekka cannot boast of any public edifices, and in this respect is, perhaps, more deficient than any other eastern city of the same size. Neither khans, for the accommodation of travellers, or for the deposit of merchandize, nor palaces of grandees, nor mosques, which adorn every quarter of other towns in the East, are here to be seen; and we may perhaps attribute this want of splendid buildings to the veneration which its inhabitants entertain for their temple; this prevents them from constructing any edifice which might possibly pretend to rival it.

The houses have windows looking towards the street; of these many project from the wall, and have their frame-work elaborately carved, or gaudily painted. Before them hang blinds made of slight reeds, which exclude flies and gnats while they admit fresh air. Every house has its terrace, the floor of which (composed of a preparation from lime-stone) is built with a slight inclination, so that the rain-water runs off through gutters into the street; for the rains here are so irregular that it is not worth while to collect the water of them in cisterns, as is done in Syria. The terraces are concealed from view by slight parapet walls; for throughout the east, it is reckoned discreditable that a man should appear upon the terrace, whence he might be accused of looking at women in the neighbouring houses, as the females pass much of their time on the terraces, employed in various domestic occupations, such as drying corn, hanging up linen, &c. The Europeans of Aleppo alone enjoy the privilege of frequenting their terraces, which are often beautifully built of stone; here they resort during the summer evenings, and often to sup and pass the night. All the houses of the Mekkawys, except those of the principal and richest inhabitants, are constructed for the accommodation of lodgers, being divided into many apartments, separated from each other, and each consisting of a sitting-room and a small kitchen. Since the pilgrimage, which has begun to decline, (this happened before the Wahaby conquest,) many of the Mekkawys, no longer deriving profit from the letting of their lodgings, found themselves unable to afford the expense of repairs; and thus numerous buildings in the out-skirts have fallen completely into ruin, and the town itself exhibits in every street houses rapidly decaying. I saw only one of recent construction; it was in the quarter of El Shebeyka, belonged to a Sherif, and cost, as report said, one hundred and fifty purses; such a house might have been built at Cairo for sixty purses.

The streets are all unpaved; and in summer time the sand and dust in them are as great a nuisance as the mud is in the rainy season, during which they are scarcely passable after a shower; for in the interior of the town the water does not run off, but remains till it is dried up. It may be ascribed to the destructive rains, which, though of shorter duration than in other tropical countries, fall with considerable violence, that no ancient buildings are found in Mekka. The mosque itself has undergone so many repairs under different sultans, that it may be called a modern structure; and of the houses, I do not think there exists one older than four centuries; it is not, therefore, in this place, that the traveller must look for interesting specimens of architecture or such beautiful remains of Saracenic structures as are still admired in Syria, Egypt, Barbary, and Spain. In this respect the ancient and far-famed Mekka is surpassed by the smallest provincial towns of Syria or Egypt. The same may be said with respect to Medina, and I suspect that the towns of Yemen are generally poor in architectural remains.

Mekka is deficient in those regulations of police which are customary in Eastern cities. The streets are totally dark at night, no lamps of any kind being lighted; its different quarters are without gates, differing in this respect also from most Eastern towns, where each quarter is regularly shut up after the last evening prayers. The town may therefore be crossed at any time of the night, and the same attention is not paid here to the security of merchants, as well as of husbands, (on whose account principally, the quarters are closed,) as in Syrian or Egyptian towns of equal magnitude. The dirt and sweepings of the houses are cast into the streets, where they soon become dust or mud according to the season. The same custom seems to have prevailed equally in ancient times; for I did not perceive in the skirts of the town any of those heaps of rubbish which are usually found near the large towns of Turkey.

With respect to water, the most important of all supplies, and that which always forms the first object of inquiry among Asiatics, Mekka is not much better provided than Djidda; there are but few cisterns for collecting rain, and the well-water is so brackish that it is used only for culinary purposes, except during the time of the pilgrimage, when the lowest class of hadjys drink it. The famous well of Zemzem, in the great mosque, is indeed sufficiently copious to supply the whole town; but, however holy, its water is heavy to the taste and impedes digestion; the poorer classes besides have not permission to fill their water-skins with it at pleasure. The best water in Mekka is brought by a conduit from the vicinity of Arafat, six or seven hours distant. The present government, instead of constructing similar works, neglects even the repairs and requisite cleansing of this aqueduct. It is wholly built of stone; and all those parts of it which appear above ground, are covered with a thick layer of stone and cement. I heard that it had not been cleaned during the last fifty years; the consequence of this negligence is, that the most of the water is lost in its passage to the city through apertures, or slowly forces its way through the obstructing sediment, though it flows in a full stream into the head of the aqueduct at Arafat. The supply which it affords in ordinary times is barely sufficient for the use of the inhabitants, and during the pilgrimage sweet water becomes an absolute scarcity; a small skin of water (two of which skins a person may carry) being then often sold for one shilling—a very high price among Arabs.