Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 345, December 6, 1828

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 12, No. 345, December 6, 1828

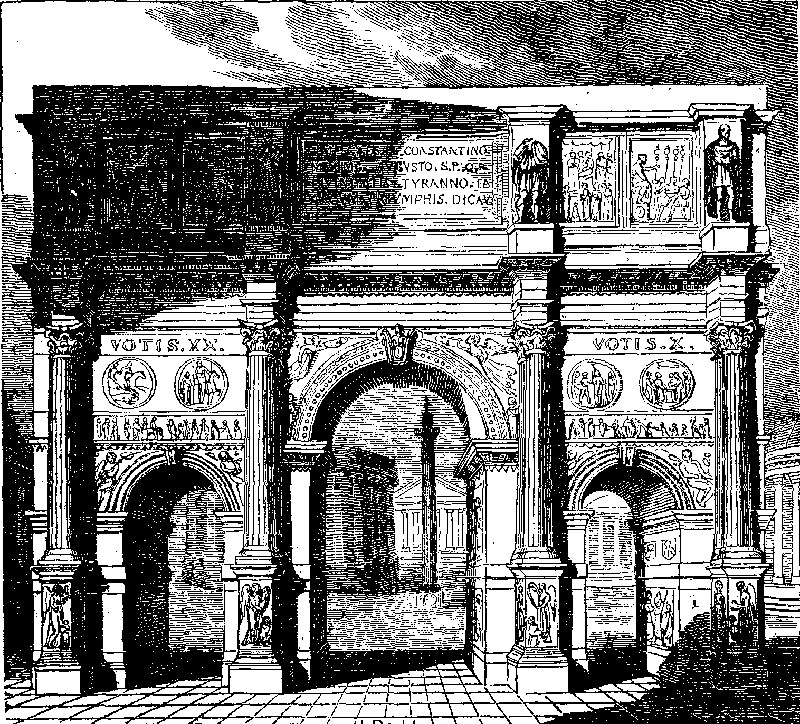

The Arch of Constantine, at Rome

"Still harping" on the Fine Arts—Architecture and Painting. Of the former, the above engraving is an illustration; and of the latter, our readers will find a beautiful subject (from one of Turner's pictures) in a Supplement published with the present Number.1

The Arches of Rome were splendid monuments of triumph, erected in honour of her illustrious generals. They were at first very simple, being built of brick or hewn stone, and of a semicircular figure; but afterwards more magnificent, built of the finest marble, and of a square figure, with a large, arched gate in the middle, and two small ones on each side, adorned with columns and statues. In the vault of the middle gate, hung winged figures of victory, bearing crowns in their hands, which, when let down, they placed on the victor's head, when he passed in triumph.

The Arch of Constantine, the most noble of all of these structures, subsists almost entire. It was erected by the senate and Roman people, in honour of Constantine, after his victory over Maxentius, and crosses the Appian Way, at the junction of the Coelian and Palatine Hills. Here it stands as the last monument of Roman triumph, or like the December sun of "the world's sole monument."

This building consists of three arches, of which the centre is the largest; and has two fronts, each adorned with four columns of giallo antico marble, of the Corinthian order, and fluted, supporting a cornice, on which stand eight Dacian captives of Pavonazzetta, or violet-coloured marble.

The inscription on both sides of the architrave imports, that it was dedicated "to the Emperor Cæsar Flavius Constantine Augustus, the greatest, pious, and the happy; because by a divine impulse, the greatness of his courage, and the aid of his army, he avenged the republic by his just arms, and, at the same time, rescued it from the tyrant and his whole faction." On one side of the arch are the words, "Liberatori urbis," to the deliverer of the city; and on the other, "Fundatori quietis," to the founder of public tranquillity.

Although erected to the honour of Constantine, this arch commemorates the victories of Trajan, some of the basso-relievos, &c. having been pilfered from one of the arches of Trajan. This accounts for the Dacian captives, whose heads Lorenzo de Medicis broke off and conveyed to Florence, but the theft might not have been so notorious to posterity, had not the artists of Constantine's time added some figures of inferior merit. Forsyth says, "Constantine's reign was notorious for architectural robbery;" and the styles of the two emperors, in the present arch, mar the harmony by their unsightly contrasts.

Although the decree for erecting this arch was, without doubt, passed immediately after the defeat of Maxentius, it appears from the monument itself, that the building was not finished and dedicated till the tenth year of Constantine's reign, or the year of Christ 315 or 316.

The newly-erected arch opposite the entrance to Hyde Park is from the Roman arch, though, we believe, not from any particular model. In the View of the New Palace, St. James's Park, (in our No. 278,) the arch, to be called the Waterloo Monument, and erected in the middle of the area of the palace, will be nearly a copy of that of Constantine at Rome. In the court-yard of the Tuilleries at Paris, there is a similar arch, copied from that of Septimius Severus. This was formerly surmounted by the celebrated group of the horses of St. Mark, pilfered from Venice, but restored at the peace of 1815.

THE BEGGAR'S DAUGHTER OF BETHNAL GREEN

(For the Mirror.)The popular ballad of "The Beggar's Daughter of Bednall-Greene" was written in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. It is founded, though without the least appearance of truth, or even probability, on a legend of the time of Henry III. Henry de Montfort, son of the ambitious Earl of Leicester, who was slain with his father at the memorable battle of Evesham, is the hero of the tale. He is supposed (according to the legend) to have been discovered among the bodies of the slain by a young lady, in an almost lifeless state, and deprived of sight by a wound, which he had received during the engagement. Under the fostering hand of this "faire damosel" he soon recovered, and afterwards marrying her, she became the mother of "the comelye and prettye Bessee." Fearing lest his rank and person should be discovered by his enemies, he disguised himself in the habit of a beggar, and took up his abode at Bethnal-Green. The beauty of his daughter attracted many suitors, and she was at length married to a noble knight, who, regardless of her supposed meanness and poverty, had the courage to make her his wife, her other lovers having deserted her on account of her low origin. Before entering, however, upon the ballad, it may not, perhaps, be thought irrelevant to give a brief sketch of the family of the De Montforts.

Simon de Montfort, created Earl of Leicester by Henry III., was the younger son of Simon de Montfort, the renowned but cruel commander of the croisade against the Albigenses. This nobleman was greatly honoured by Henry III., to whose sister, the Countess Dowager of Pembroke, he paid his addresses, and was married, with the consent of her brother. For the favour thus shown him by his sovereign, he, however, proved ungrateful: his inordinate ambition, cloaked by a pretended zeal for reform, was the cause of those rebellions which, in the reign of Henry III., kept the kingdom in such a continued turmoil. The different oppressions and successes of the confederate barons, who at length got possession of the king's person, and the civil wars which ensued, are so well known as to render any remark on the subject superfluous; suffice it to say, that the disputes between the malcontents and the royal party were at length terminated by the battle of Evesham, which decided in favour of the latter. In this field fell the Earl of Leicester and his eldest son, Henry de Montfort. His death was followed by the total ruin of his family; his titles and estates were all confiscated; the countess, his wife, who had been extremely active in her designs against the royalists, was banished, together with her sons, Simon and Guy, who afterwards assassinated their cousin, Henry d'Allmane, when he was endeavouring to effect a reconciliation between them and their uncle, Henry IV. The head of the earl was sent as a signal of the victory by Roger de Mortimer to the countess; but his body, together with that of his son Henry, was interred in the Abbey of Evesham; thus leaving the improbability of the legend without a shadow of doubt.

As our limits will not allow us to quote the whole of the ballad,2 we must content ourselves with giving the song of the beggar, which, as well as being the most interesting, contains the whole of the legend concerning de Montfort:—

A poore beggar's daughter did dwell on a greene,Who for her fairnesse might well be a queene:A blithe bonny lasse, and a daintye was shee,And many one called her pretty Bessee.Her father hee had noe goods nor noe land,But begg'd for a penny all day with his hand;And yett to her marriage he gave thousands three,And still he hath somewhat for pretty Bessee.And if any one here her birth doe disdaine,Her father is ready, with might and with maine,To prove shee is come of noble degree—Therefore, ever flout att prettye Bessee.Then give me leave, nobles and gentles, each one,One song more to sing, and then I have done;And if that itt may not winn good report,Then doe not give me a GROAT for my sport.Sir Simon de Montfort my subject shall bee.Once chiefe of all the great barons was hee—Yet fortune so cruelle this lorde did abase,Now loste and forgotten are hee and his race.When the barons in armes did King Henrye oppose,Sir Simon de Montfort their leader they chose—A leader of courage undaunted was hee,And oft-times he made their enemyes flee.At length in the battle on Eveshame plaineThe barons were routed, and Montfort was slaine;Moste fatall that battel did prove unto thee,Thoughe thou wast not borne then, my prettye Bessee!Along with the nobles that fell at that tyde,His eldest son Henrye, who fought by his side,Was fellde by a blowe he receiv'de in the fighte!A blowe that depriv'de him for ever of sight.Among the dead bodyes all lifelesse he laye,Till evening drewe on of the following daye,When by a yong ladye discover'd was hee—And this was thy mother, my prettye Bessee!A baron's faire daughter stept forth in the nighte,To search for her father, who fell in the fight,And seeing yong Montfort, where gasping he laye,Was moved with pitye, and broughte him awaye.In secrette she nurst him, and swaged his paine,While he throughe the realme was beleev'd to be slaine:At lengthe his faire bride she consented to bee,And made him glad father of prettye Bessee.And nowe, lest oure foes our lives sholde betrayeWe clothed ourselves in beggars' arraye;Her jewells shee solde, and hither came wee—All our comfort and care was our prettye Bessee.And here have wee lived in fortunes despite,Thoughe poore, yet contented with humble delighte;Full forty winters thus have I beeneA silly blind beggar of Bednall-greene.And here, noble lordes, is ended the songOf one that once to your owne ranke did belong:And thus have you learned a secrette from mee,That ne'er had beene knowne but for prettye Bessee.At Bethnal-Green is an old mansion, which, in the survey of 1703, was called Bethnal-Green-House, and which the inhabitants, with their usual love of traditionary lore, assign as the "Palace of the Blind Beggar." This house was erected in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, by John Kirby, citizen of London, and was, says Stow,3 "lofty like a castle." It was afterwards the residence of Sir Hugh Platt, Knight, the author of many ingenious works; from him it came into the possession of Sir William Ryder, Knight, who died there in 1669; of late years it has been used as a private madhouse. The tradition of the beggar is still preserved on the sign-posts of several of the public-houses in the neighbourhood.

S.I.B.HISTORY AND ANTIQUITY OF WILLS

(For the Mirror.)According to Blackstone, wills are of high antiquity. We find them among the ancient Hebrews; not to mention what Eusebius and others have related of Noah's testament, made in writing, and witnessed under his seal, by which he disposed of the whole world. A more authentic instance of the early use of testaments occurs in the sacred writings, (Genesis, chap. xlviii.) in which Jacob bequeaths to his son Joseph, a portion of his inheritance, double to that of his brethren.

The Grecian practice concerning wills (says Potter) was not the same in all places; some states permitted men to dispose of their estates, others wholly deprived them of that privilege. We are told by Plutarch, that Solon is much commended for his law concerning wills; for before his time no man was allowed to make any, but all the wealth of deceased persons belonged to their families; but he permitted them to bestow it on whom they pleased, esteeming friendship a stronger tie than kindred, and affection than necessity, and thus put every man's estate in the disposal of the possessor; yet he allowed not all sorts of wills, but required the following conditions in all persons that made them:—

1st. That they must be citizens of Athens, not slaves, or foreigners, for then their estates were confiscated for the public use.

2nd. That they must be men who have arrived to twenty years of age, for women and men under that age were not permitted to dispose by will of more than one medimn of barley.

3rd. That they must not be adopted; for when adopted persons died without issue, the estates they received by adoption returned to the relations of the men who adopted them.

4th. That they should have no male children of their own, for then their estate belonged to these. If they had only daughters, the persons to whom the inheritance was bequeathed were obliged to marry them. Yet men were allowed to appoint heirs to succeed their children, in case these happened to die under twenty years of age.

5th. That they should be in their right minds, because testaments extorted through the phrenzy of a disease, or dotage of old age, were not in reality the wills of the persons that made them.

6th. That they should not be under imprisonment, or other constraint, their consent being then only forced, nor in justice to be reputed voluntary.

7th. That they should not be induced to it by the charms and insinuations of a wife; for (says Plutarch) the wise lawgiver with good reason thought that no difference was to be put between deceit and necessity, flattery and compulsion, since both are equally powerful to persuade a man from reason.

Wills were usually signed before several witnesses, who put seals to them for confirmation, then placed them in the hands of trustees, who were obliged to see them performed. At Athens, some of the magistrates were very often present at the making of wills. Sometimes the archons were also present. Sometimes the testator declared his will before sufficient witnesses, without committing it to writing. Thus Callias, fearing to be cut off by a wicked conspiracy, is said to have made an open declaration of his will before the popular assembly at Athens. There were several copies of wills in Diogenes Laertius, as those of Aristotle, Lycon, and Theophrastus; whence it appears they had a common form, beginning with a wish for life and health.

The most ancient testaments among the Romans were made vivâ voce, the testator declaring his will in the presence of seven witnesses; these they called nuncupative testaments; but the danger of trusting the will of the dead to the memory of the living soon abolished these; and all testaments were ordered to be in writing.

The Romans were wont to set aside testaments, as being inofficiosa, deficient in natural duty, if they disinherited or totally passed by (without assigning a true and sufficient reason) any of the children of the testator. But if the child had any legacy, though ever so small, it was a proof that the testator had not lost his memory nor his reason, which otherwise the law presumed. Hence probably (says Blackstone) has arisen that groundless, vulgar error of the necessity of leaving the heir a shilling, or some other express legacy, in order to effectually disinherit him; whereas the law of England, though the heir, or next of kin, be totally omitted, admits no querela inofficiosa, to set aside such testament.

Alfred the Great made a will, wherein he declared, in express terms, that it was just the English should be as free as their own thoughts.

P.T.W.The Cosmopolite

DANCING(For the Mirror.)Dancing is defined to be "to move in measure; to move with steps correspondent to the sound of instruments." But there are other species of dancing—as

—–for three long monthsTo dance attendance for a word of audience:and to dance with pain, or when, as Lord Bacon says, "in pestilences, the malignity of the infecting vapour danceth the principal spirits." The Chorea S. Viti, or St. Vitus's Dance is another variation, said to have once prevailed extensively, and to have been cured by a prayer to this saint! whose martyrdom is commemorated on June 15. It may not be generally known that a person afflicted with this species of dancing can run, although he cannot walk or stand still. Another and a more agreeable species is to lead the dance, an unjust usurpation which is practised in a thousand other places beside the ball-room.

According to the mythologists, (authorities always quotable, and nobody knows why,) the Curetes or Corybantes, a people of Crete, who were produced from rain, first invented the dance to amuse the infant Jupiter—with what success he danced we know not, for when a year old he waged war against the Titans, and then his dancing days must have terminated.

A history of dancing is, however, not to our purpose; but a few of its eccentricities. It occurs in the customs of all people, either as a recreation or as a religious ceremony—held in contempt by some, and in esteem by others. David danced before the ark; the daughters of Shiloh danced in a solemn yearly festival; and the Israelites, (good judges) danced round the golden calf.

The ancients had a peculiar penchant for dancing, whether in person or by animals; and the feats of the latter distance all the wretched efforts of the bears, dogs, and horses of our days. The attempts of Galba to amuse the Roman people throw into the shade all the peace-rejoicings and illuminations of St. James's and the Green Parks. Suetonius, Seneca, and Pliny tell us of elephants in their time that were taught to walk the rope, backwards and forwards, up and down, with the agility of an Italian rope-dancer. Such was the confidence reposed in the docility and dexterity of the animal, that a person sat upon an elephant's back, while he walked across the theatre upon a rope, extended from the one side to the other. Lipsius, who has collected these testimonies, thinks them too strong to be doubted—perhaps even stronger than the rope. Scaliger corroborates all of them; Busbequius saw an elephant dance a pas seul at Constantinople; and Suetonius tells us of twelve elephants, six male and six female, who were clothed like men and women, and performed a country dance, in the reign of Tiberius. In later times, horses have been taught to dance. In the carousals of Louis XIII. there were dances of horses; and in the 13th century, some rode a horse upon a rope. All this eclipses the puny modern feats of Astley and Ducrow.4

The Greeks and Romans were divided upon the propriety of dancing. Socrates who held death in contempt, when a reverend old gentleman, learned to dance of Aspasia, the beautiful nurse of Grecian eloquence. The Romans forgot their loss of the republic and of liberty—

—–the air we breatheIf we have it not we die.in seeing Pylades and Bathyllus dance before them in their theatres—an indifference of which we were reminded on hearing that the Parisians sat in the Cafés on the Boulevard du Italiens—sipping coffee and sucking down ice, during the capitulation of the city, and while the French, killed and wounded, were conveyed along the road before them.

Cato, Censorius, danced at the age of fifty-six. Cicero, however, reproached a consul with having danced. Tiberius, that monster of indulgences, banished dancers from Rome; and Domitian, the illustrious fly-catcher, expelled several of his members of parliament for having danced. We are much more civilized, for such an edict as that of Domitian would clear our senate-houses as effectually as when Cromwell turned out the Long Parliament.

Among the Italians and the French even there have been found enemies to dancing. Alfieri, the poet, had a great aversion to dancing; and one Daneau wrote a Traité des Danses, in which he maintains that "the devil never invented a more effectual way than dancing, to fill the world with –." The bishop of Noyon once presided at some deliberations respecting a minuet; and in 1770, a reverend prelate presented a document on dancing to the king of France. The Quakers consider dancing below the dignity of the Christian character; and an enthusiast, of another creed, thinks all lovers of the stage belong to the schools of Voltaire and Hume, and that dancing is a link in the chain of seduction. Stupid, leaden-heeled people, who constantly mope in melancholy, and neither enjoy nor impart pleasure, will naturally be enemies to dancing; and such we are induced to think the majority of these opponents.

The French are inveterate dancers. They have their bals parés and their salons de danse in every street; and as long as the weather will permit, they dance on platforms out of doors, and a heavy shower of rain will scarcely cool their ardour in the recreation. Some of their stage figurantes resemble aerial beings rather than bone and blood, for flesh may almost be left out of the composition. But the Italians are a nation of dancers as well as the children of song, and they seem to have followed the noble example of old Cato, in this respect, with better effect than they have studied his virtue. We are also told upon good authority, that the American dancers equal any of the European figurantes.

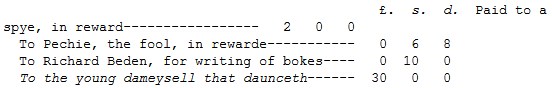

The English people have always been lovers of dancing; and it forms an accompaniment of almost all their old sports and pastimes. Witness the maypoles, wassails, and wakes of rural life, and the grotesque morris-dance, originating in a kind of Pyrrhic or military dance, and described by Sir William Temple as composed of "ten men, who danced a maid marian and a tabor and pipe." In the time of Henry VII. dancers were remarkably well paid; for in some of his accounts in the Exchequer, we find

In Shakspeare's time, to dance was an elegant accomplishment. Thus in the "Merry Wives of Windsor," "What say you to young Mr. Fenton? He capers, he dances, he has eyes of youth, he writes verses." Locke thus alludes to the graceful motions which dancing lends to the human frame: "the legs of the dancing-master, and the fingers of a musician, fall, as it were, naturally, without thought or pains, into regular and admirable motions."

It must be somewhat surprising to those who over-rate the matter-of-fact character of the English people, that so great a majority of them are attached to dancing. Among rank and wealth this amusement admits of a finer display of beauty and artificial decoration than almost any other recreation; for nothing can be more splendid than a brilliantly illuminated and well-filled ball-room. Dancing among the middle classes of society is equally mirthful though not of so ostentatious a character, and it is a question whether the latter, being free from the alloy of fashionable follies, are not more exhilarated by sweet sounds than their wealthy superiors. But the mushroom aristocracy and pride of purse often operate as checks to the enjoyment of both these classes; and splendid dancing accommodations sometimes put an end to the amusement. At Dorking, in Surrey, attached to one of the inns is a ball-room, which cost the builder £12,000, and here is one, or at most three balls during the year, while at scores of places within our recollection, of less consequence, there are monthly and even weekly balls; and we are inclined to think these periodical recreations of great importance to the happiness of country towns. But there is a species of intoxication sometimes arising from them—that of dancing all night, to suffer from exhaustion and rheumatism on the following day—an evil easy of remedy, by such amusements being more frequent and less protracted. The influence on the character of the people would probably be that of rendering it more even, from the admixture or reciprocation of pleasure and business being more proportional. This plan would get rid of much of the ostentation and expense of a country ball, and would ultimately prove the best antidote to the sins of scandal.

As we have spoken of public dancing in the time of Henry VII., we will show that the enormous sums paid to artists have nourished their conceit to an alarming height. Pitrot, the Vestris of his day, was a consummate specimen of this effrontery. At Vienna, he chose to appear only in the last act of the ballet. The emperor desired him to come forth at the end of the first; Pitrot refused; the court left the opera, and then Pitrot told the dancers they would have a hop by themselves, which they did. However, this was forgiven; and, at his departure, he was presented with the emperor's picture, set with brilliants. Pitrot received it with sang froid, pressed his thumb upon the crystal, crushed the picture to pieces, adding, "Thus I treat men not worthy of my friendship." This fellow behaved equally ill in France, Prussia, and Russia; but, at length, scouted by all his patrons, and, after giving his thousands to opera girls, he wandered about Calais in rags and poverty. Farinelli, after accumulating a fortune in England, built a superb mansion in Italy, which he called the English Folly.5