Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 334, October 4, 1828

In a picture painted by F. Chello della Puera, the Virgin Mary is placed on a velvet sofa, playing with a cat and a paroquet, and about to help herself to coffee from an engraved coffee-pot.

In another, painted by Peter of Cortona, representing the reconciliation of Jacob and Laban, (now in the French Museum), the painter has represented a steeple or belfry rising over the trees. A belfry in the mountains of Mesopotamia, in the time of Jacob!

N. Poussin's celebrated picture, at the same place, of Rebecca at the Well, has the whole back-ground decorated with Grecian architecture.

Paul Veronese placed Benedictine fathers and Swiss soldiers among his paintings from the Old Testament.

A painter, intending to describe the miracle of the fishes listening to the preaching of St. Anthony of Padua, painted the lobsters, who were stretching out of the water, red! probably having never seen them in their natural state. Being asked how he could justify this anachronism, he extricated himself by observing, that the whole affair was a miracle, and that thus the miracle was made still greater.

In the Notices des MSS. du Roi VI. 120, in the illuminations of a manuscript Bible at Paris, under the Psalms, are two persons playing at cards; and under Job and the Prophets are coats of arms and a windmill.

Poussin, in his picture of the Deluge has painted boats, not then invented. St. Jerome, in another place, with a clock by his side; a thing unknown in that saint's days.—Nous revenons.

THE TOPOGRAPHER

VIRGINIA WATER,(The favourite Retreat of his Majesty.)Virginia Water was planted, and the lake executed, under the direction of Paul Sandby, at a time when this part of Windsor Forest was the favourite residence of Duke William of Cumberland. The artificial water is the largest in the kingdom, with the single exception of Blenheim; the cascade is, perhaps, the most striking imitation we have of the great works of nature; and the grounds are arranged in the grandest style of landscape-gardening. The neighbouring scenery is bold and rugged, being the commencement of Bagshot Heath; and the variety of surface agreeably relieves the eye, after the monotony of the first twenty miles from town, which fatigues the traveller either upon the Bath or Western roads. At the time when the public were allowed to visit Virginia Water, the best point of entrance was at the gate at Bishopsgate; near which very pretty village, or rather green, the Royal Lodge is at present situated. Shelley, who had a true eye for the picturesque, resided for some time at this place; and it would have been difficult for a poet to have found, in any of the highly cultivated counties of England, a spot so full of the most exquisite variety of hill and dale, of wood and water,—so fitted to call forth and cherish the feelings upon which poetry must depend for its peculiar nurture.

Bishopsgate is situated about a mile to the right of the western road from London, after you ascend the hill beyond Egham. To the left, St. Anne's Hill, the favoured residence of Charles Fox, is a charming object; and upon the ridge which the traveller ascends, is the spot which has given a name to Denham's celebrated poem. "Cooper's Hill" is not shut out from the contemplative searchers after the beauties of nature; and, however the prospect here may be exceeded by scenes of wider extent, or more striking grandeur, certainly the locale of the earliest, and perhaps the best, descriptive poem of our language, is calculated to produce the warmest feelings of admiration, both for its actual beauty and its unrivalled associations. From an elevation of several hundred feet, you look down upon a narrow fertile valley, through which the Thames winds with surpassing loveliness. Who does not recollect the charming lines with which Denham describes the "silver river:"—

"Oh! could I flow thee, and make thy streamMy great example, as it is my theme;Though deep, yet clear; though gentle, yet not dull;Strong without rage; without o'erflowing full."Immediately at your feet is the plain of Runnemede, where the great battle between John and the Barons was fought; and in the centre of the river is the little fishing island, where Magna Charta was signed. At the extremity of the valley is Windsor Castle, rising up in all the pomp of its massive towers. We recollect the scene as Windsor was. Whatever Mr. Wyattville may have done for its internal improvement, and for its adaptation to the purposes of a modern residence without sacrificing all its character of antiquity, we fear that he has destroyed its picturesque effect in the distant landscape. Its old characteristic feature was that of a series of turrets rising above the general elevation. By raising the intermediate roofs, without giving a proportionate height to the towers, the whole line has become square and unbroken. This was, perhaps, an unavoidable fault; but it is a fault.

From Cooper's Hill, the entrance to Virginia Water is a walk of a quarter of an hour. We were accustomed to wander down a long and close plantation of pines, where the rabbit ran across with scarcely a fear of man. A more wild and open country succeeded; and we then followed the path, through many a "bosky bourn," till we arrived at a rustic bridge, which crossed the lake at a narrow neck, where the little stream was gradually lost amongst the underwood. A scene of almost unrivalled beauty here burst upon the view. For nearly a mile, a verdant walk led along, amidst the choicest evergreens, by the side of a magnificent breadth of water. The opposite shore was rich with the heather-bloom; and plantations of the most graceful trees—the larch, the ash, and the weeping birch ("the lady of the woods"), broke the line of the wide lake, and carried the imagination on, in the belief that some mighty river lay beyond that screening wood. The cascade was at length reached. Cascades are much upon the same plan, whether natural or artificial; the scale alone makes the difference. This cascade is sufficiently large not to look like a plaything; and if it were met with in Westmoreland or Wales, tourists would dilate much upon its beauties. At this point the water may be easily forded; and after a walk of the most delicious seclusion, we used to reach a bold arch, over which the public road was carried. Here have been erected some of the antique columns, that, a few years ago, were in the court-yard of the British Museum.

From this arch a variety of walks, of the most delightful retirement, present themselves. They are principally bounded with various trees of the pine tribe, intermingled with laurel and acacia. The road gradually ascends to a considerable elevation, where there is a handsome building, called the Belvidere. The road from this spot is very charming. We descend from this height, through a wild path, by the side of trees of much more ancient growth than the mass around; and, crossing the high road, again reach the lake, at a point where its dimensions are ample and magnificent. About this part a splendid fishing-temple has lately been erected. Of its taste we can say nothing.

The common road from Blacknest (the name of this district of Windsor Forest) to the Royal Lodge is strikingly beautiful. Virginia Water is crossed by a very elegant bridge, built by Sandby; on one side of it the view terminates in a toy of the last age—a Chinese temple; on the other it ranges over a broad expanse of water. The road sometimes reminds one of the wildness of mountain scenery, and at another turn displays all the fertility of a peaceful agricultural district. We at length pass the secluded domain of the Royal Lodge; and when we reach the edge of the hill, we look upon a vista of the most magnificent elms, and over an expanse of the most striking forest scenery, with the splendid Castle terminating the prospect—a monument of past glories, which those who have a feeling for their country's honour may well uphold and cherish.– London Magazine.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

TEAThe principal article of our commerce with China, namely, tea, is, perhaps, more singular in its history than any other article of commerce in the known world. A simple and unsophisticated shrub, in little more than half a century, has become an article of such general consumption, that it seems to form one of the prime articles of existence among the great bulk of mankind. It is the peculiar growth of a country, of which it forms almost the only link of connexion with the rest of the world. It forms the source of the largest commercial revenue to the British Government of any other commodity whatever, and of the largest commercial profits to the individuals concerned in its importation. Withal, it is the simplest, the most harmless thing that ever was offered to the gratification of man,—having, it is believed and argued by many, a moral influence wherever it is diffused. It is the rallying point of our earliest associations; it has ever given an additional charm to our firesides; and tends, perhaps, more than any one thing, to confirm the pre-existing domestic habits of the British public. Its exhilarating qualities are eagerly sought after as a restorative and solace from the effects of fatigue or dissipation; the healthy and the sick, the young and the old, all equally resort to the use of it, as yielding all the salutary influence of strong liquors, without their baneful and pernicious effects. Yet this shrub, so simple and so useful, is delivered to the community of this country, so surcharged with duties and profits beyond its original cost, that, did it contain all the mischievous qualities that are opposed to its real virtues, it could not be more strictly guarded from general use.

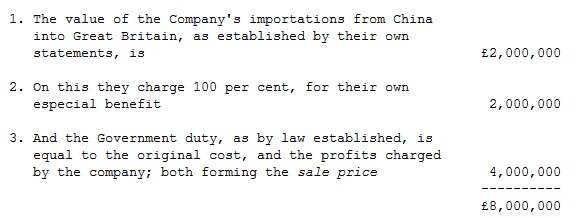

For the whole of our imports, including factory expenses and commission, the original cost in China amounts to the sum of two millions sterling. This is wonderfully increased before the British public can have any access to the article of consumption; thus:—

Oriental Herald.

DEATH OF YOUNG PARKIt is quite inconceivable with what increased zeal new candidates for African discovery come forward the moment that the death of any fresh victim to this pestilential country is announced. To the list of those who have already fallen, may be added young Park, the son of the late enterprising Mungo Park, and a midshipman of his majesty's ship Sybille. He went out in this ship with a full determination to proceed on foot, and alone, from the coast to the spot where his father perished, in the hope of hearing some authentic and more detailed account of the catastrophe than had yet been received. With leave of the commodore, he set out from Accra, and proceeded as far as Yansong, the chief town of Acquimbo, distant from the coast about one hundred and forty miles. Here the natives were celebrating the Yam feast, a sort of religious ceremony, to witness which Park got up into a Fetish tree, which is regarded by the natives with fear and dread. Here he remained a great part of the day, exposed to the sun, and was observed to drink a great quantity of palm wine. In dropping down from one of the lower branches, he fell on the ground, and said, that he felt a severe shock in his head. He was that evening seized with a fever, and died in three days, on the 31st October, 1827. As soon as the king, Akitto, heard of his death, he ordered all his baggage to be brought to his house, and instantly despatched a messenger to Accra, first making him swear "by the head of his father," that he would not sleep till he had delivered the message; it was to inform the resident of the event, and that all the property of the deceased would be forthwith sent down to Accra. This was accordingly done, and it did not appear on examination, that a single article was missing; even an old hat, without a crown, was not omitted. There was an idle report of Park being poisoned, for which there appears not the slightest foundation.—Q. Rev.

DIRGETO THE MEMORY OF MISS ELLEN GEE, OF KEW,Who died in consequence of being stung in the eyePeerless, yet hapless maid of Q!Accomplish'd LN G!Never again shall I and UTogether sip our T.For, ah! the Fates, I know not Y,Sent midst the flowers a B,Which ven'mous stung her in the I,So that she could not C.LN exclaim'd, "Vile, spiteful B!If ever I catch UOn jess'mine, rosebud, or sweet P,I'll change your stinging Q."I'll send you, like a lamb or U,Across the Atlantic C,From our delightful village Q,To distant OYE."A stream runs from my wounded I,Salt as the briny C,As rapid as the X or Y,The OIO, or D."Then fare thee ill, insensate B!Who stung, nor yet knew Y;Since not for wealthy Durham's CWould I have lost my I."They bear with tears fair LN GIn funeral RA,A clay-cold corse now doom'd to B,Whilst I mourn her DK.Ye nymphs of Q, then shun each B,List to the reason Y!For should a B C U at T,He'll surely sting your I.Now in a grave, L deep in Q,She's cold as cold can B;Whilst robins sing upon A U,Her dirge and LEG.New Monthly Magazine.

LINES SENT WITH A GOOSE"When this you see,Remember me,"Was long a phrase in use,And so I sendTo you, dear friend,My proxy. "What?" A goose!THE GATHERER

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.SHAKSPEARECORPORATION LEARNINGAt a late meeting of a certain corporation in Dorsetshire, for the nomination of a person to fill the office of Mayor, a sufficient number of the burgesses not being in attendance, it was intimated that an application would be made for a Mandamus, when one of "the worthy electors," being un-"learned in the law," innocently remarked, "I hope he will come, and then he'll put un all right and make un elect one."

Sept. 25, 1828.

This is not a Joe Miller joke, but one of actual and recent occurrence; although there is a similar story fathered on a sapient civic authority.

SELLING A WOMANThe value that was set upon the bond-servants in the West Indies, is curiously exemplified in the following anecdote:—

There was a planter in Barbadoes that came to his neighbour, and said to him, "Neighbour, I hear you have lately brought good store of servants out of the last ship that came from England; and I hear withal that you want provisions. I have great want of a woman servant, and would be glad to make an exchange. If you will let me have some of your woman's flesh, you shall have some of my hog's flesh." So the price was set, a groat a-pound for the hog's flesh, and sixpence for the woman's. The scales were set up, and the planter had a maid that was extremely fat, lazy, and good for nothing; her name was Honour. The man brought a great fat sow, and put it in one scale, and Honour was put in the other. But when he saw how much the maid outweighed his sow, he broke off the bargain and would not go on.

SMOKINGSuch is the passion for smoking at Hamburgh, that children about ten years of age may be seen with pipes in their mouths, whiffing with great gravity and composure.

PUBLIC ROADSThe turnpike-roads of England are above twenty thousand miles in length, and upwards of a million sterling is annually expended in their repair and maintenance.

John Bulwer, M.D. was author of many books, the most curious of which were his "Anthropo Metamorphoses," and "Pathomyotomia." We might conclude he was of Irish extraction; St. Patrick, the old song says, "ne'er shut his eyes to complaints," and Bulwer in his "Instructions to the Deaf and Dumb," tells us they are intended "to bring those who are so born to hear the sound of words with their eyes!"—Wadd's Memoirs.

CRANIOLOGYPhilosophy is a very pleasant thing, and has various uses; one is, that it makes us laugh; and certainly there are no speculations in philosophy, that excite the risible faculties, more than some of the serious stories related by fanciful philosophers.—One man cannot think with the left side of his head; another, with the sanity of the right side judges the insanity of the left side of his head. Zimmerman, a very grave man, used to draw conclusions as to a man's temperament, from his nose!—not from the size or form of it, but the peculiar sensibility of the organ; while some have thought, that the temperature of the atmosphere might be accurately ascertained by the state of its tip! and Cardan considered acuteness of the organ a sure proof of genius!—Ibid.

WILSON THE PAINTERThe late Mr. Christie, the auctioneer, while selling a collection of pictures, having arrived at a chef-d'oeuvre of Wilson's, was expatiating with his usual eloquence on its merits, quite unaware that Wilson himself had just before entered the room. "This gentlemen, is one of Mr. Wilson's Italian pictures; he cannot paint anything like it now." "That's a lie!" exclaimed the irritated artist, to Mr. Christie's no small discomposure, and to the great amusement of the company; "he can paint infinitely better."

SCOTCH DEGREEA few years since, a vain old country surgeon obtained a diploma to practice, and called on Dr. H–, of Bath, with the important intelligence. At dinner, the doctor asked his new brother, if the form of diplomas ran now in the same style as at the early commencement of those honours? "Pray Sir, what might that form be?" says the surgeon, "I'll give it to you," replied our Galen, when stepping to his daughter's harpsichord, he sung the following prophecy of the Witches to Macbeth:

He must, he must,He shall, he shallSpill much more bloodAnd become worse,To make his title good."That, sir, was the true ancient mode of conferring a Scotch degree on Dr. Macbeth."

G.J.YTHREE FACESThree faces wears the doctor; when first soughtAn angel's—and a god's the cure half wrought;But when, that cure complete, he seeks his fee,The devil looks then less terrible than he.This epigram is illustrated by the following conversation, which passed between Bouvart and a French marquis, whom he had attended during a long and severe indisposition. As he entered the chamber on a certain occasion, he was thus addressed by his patient: "Good day to you, Mr. Bouvart; I feel quite in spirits, and think my fever has left me."—"I am sure of it, " replied the doctor; "the very first expression you used convinces me of it."—"Pray explain yourself."—"Nothing more easy; in the first days of your illness, when your life was in danger, I was your dearest friend; as you began to get better, I was your good Bouvart; and now I am Mr. Bouvart; depend upon it you are quite recovered."

LYINGA Dutch ambassador, entertaining the king of Siam with an account of Holland, after which his majesty was very inquisitive, amongst other things told him, that water in his country would sometimes get so hard, that men walked upon it; and that it would bear an elephant with the utmost ease. To which the king replied, "Hitherto I have believed the strange things you have told me, because I looked upon you as a sober, fair man; but now I am sure you lie."

1

Having, not long since, purchased a bottle of Persian Otto, warranted genuine, (as is all) I laid it carefully by, wrapped thickly round with cotton wool; the Atar which was certainly excellent, was in a curious bottle of rough misshapen workmanship, but ornamented with sundry circles, and lozenges, of various coloured glass. I was inclined to regard this bottle as a more genuine specimen of oriental art, than one of those, which, enamelled, with gold, stands forth in its way an elegant of the first water, and I hoped to have kept it long. On visiting my Otto shortly afterwards, I found that not only had it all evaporated, but destroyed its receptacle. Its strength (I conclude) had dissolved the cement of the aforesaid coloured bits of glass, and left me only an empty and plain bottle, the ugliest of the ugly. I mention this circumstance as a caution to amateurs in Atar Gul.

2

I imagine this to mean the time of the introduction of the sport, and the year when the company was instituted.

3

The idea of the ancient Egyptians, as mentioned by Herodotus, having been of the same family as the Negroes, is now completely refuted by the inquiries of Cuvier and other naturalists. The examinations of mummies have been highly useful in setting this question at rest.