Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 287, December 15, 1827

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 10, No. 287, December 15, 1827

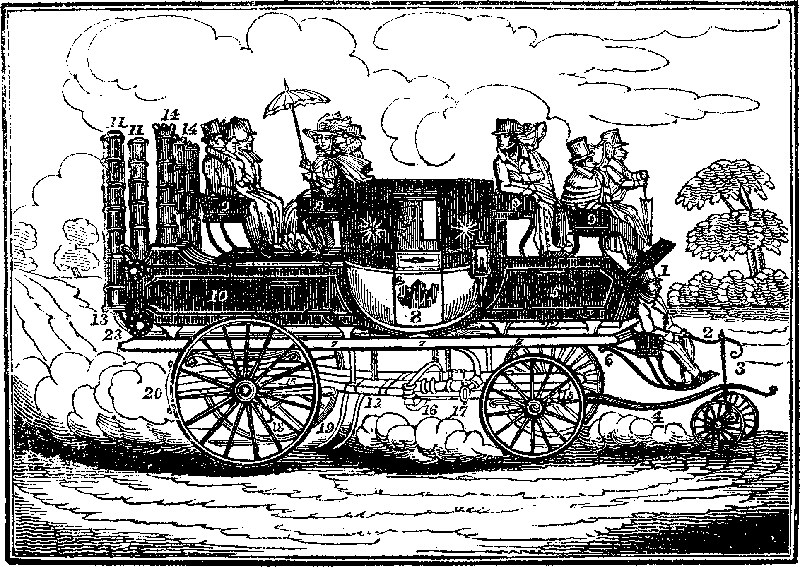

1. The Guide and Engineer, to whom the whole management of the machinery and conduct of the carriage is intrusted. Besides this man, a guard will be employed.

2. The handle which guides the Pole and Pilot Wheels.

3. The Pilot Wheels.

4. The Pole.

5. The Fore Boot, for luggage.

6. The "Throttle Valve" of the main steam-pipe, which, by means of the handle, is opened or closed at pleasure, the power of the steam and the progress of the carriage being thereby regulated from 1 to 10 or 20 miles per hour.

7. The Tank for Water, running from end to end, and the full breadth of the carriage; it will contain 60 gallons of water.

8. The Carriage, capable of holding six inside-passengers.

9. Outside Passengers, of which the present carriage will carry 15.

10. The Hind Boot, containing the Boiler and Furnace. The Boiler is incased with sheet-iron, and between the pipes the coke and charcoal are put, the front being closed in the ordinary way with an iron door. The pipes extend from the cylindrical reservoir of water at the bottom to the cylindrical chamber for steam at the top, forming a succession of lines something like a horse-shoe, turned edgeways. The steam enters the "separators" through large pipes, which are observable on the Plan, and is thence conducted to its proper destination.

11. "Separators," in which the steam is separated from the water, the water descending and returning to the boiler, while the steam ascends, and is forced into the steam-pipes or main arteries of the machine.

12. The Pump, by which the water is pumped from the tank, by means of a flexible hose, to the reservoir, communicating with the boiler.

13. The Main Steam Pipe, descending from the "separators," and proceeding in a direct line under the body of the coach to the "throttle valve" (No. 6,) and thence, under the tank, to the cylinders from which the pistons work.

14. Flues of the Furnace, from which there is no smoke, coke and charcoal being used.

15. The Perches, of which there are three, conjoined, to support the machinery.

16. The Cylinders. There is one between each perch.

17. Valve Motion, admitting steam alternately to each side of the pistons.

18. Cranks, operating on the axle: at the ends of the axle are crotches (No. 21,) which, as the axle turns round, catch projecting pieces of iron on the boxes of the wheels, and give them the rotatory motion. The hind wheels only are thus operated upon.

19. Propellers, which, as the carriage ascends a hill, are set in motion, and move like the hind legs of a horse, catching the ground, and then forcing the machine forward, increasing the rapidity of its motion, and assisting the steam power.

20. The Drag, which is applied to increase the friction on the wheel in going down a hill. This is also assisted by diminishing the pressure of the steam—or, if necessary, inverting the motion of the wheels.

21. The Clutch, by which the wheel is sent round.

22. The Safety Valve, which regulates the proper pressure of the steam in the pipe.

23. The Orifice for filling the Tank. This is done by means of a flexible hose and a funnel, and occupies but a few seconds.

Mr. Goldsworthy Gurney, whose name is already familiar to most of our readers, after a variety of experiments, during the last two years, has completed a STEAM CARRIAGE on a new principle; or, as a wag said the other day, he has at length brought his plan to bear. We have, accordingly, procured a drawing of this extraordinary invention, which we shall proceed to describe generally, since the letters, introduced in the annexed Engraving, with the accompanying references, will enable our readers to enter into the details of the machinery:—First, as to its safety, upon which point the public are most sceptical. In the present invention, it is stated, that, even from the bursting of the boiler, there is not the most distant chance of mischief to the passengers. This boiler is tubular, constructed upon philosophical principles, and upon a plan totally distinct from any thing previously in use. Instead of being, as in ordinary cases, a large vessel closed on all sides, with the exception of the valves and steam conductors, which a high pressure or accidental defect may burst, it is composed of a succession of welded iron pipes, perhaps forty in number, screwed together in the manner of the common gas-pipes, at given distances, extending in a direct line, and in a row, at equal distances from a small reservoir of water, to the distance of about a yard and a half, and then curving over in a semi-circle of about half a yard in diameter, returning in parallel lines to the pipes beneath, to a reservoir above, thus forming a sort of inverted horse-shoe. This horse-shoe of pipes, in fact, forms the boiler, and the space between is the furnace; the whole being enclosed with sheet-iron. The advantage of this arrangement is obvious; for, while more than a sufficient quantity of steam is generated for the purposes requited, the only possible accident that could happen would be, the bursting of one of these barrels, and a temporary diminution of the steam-power of one-fortieth part. The effects of the accident could, of course, only be felt within its own enclosure; and the Engineer could, in ten minutes, repair the injury, by extracting the wounded barrel, and plugging up the holes at each end; but the fact is, that such are the proofs to which these barrels are subjected, before they are used, by the application of a steam-pressure five hundred times more than can ever be required, that the accident, trifling as it is, is scarcely possible.

A contemporary journal illustrates Mr. Gurney's invention by the following analogy:—"It will appear not a little singular that Mr. Gurney, who was educated a medical man, has actually made the construction of the human body, and of animals in general, the model of his invention. His reservoirs of steam and water, or rather 'separators,' as they are called, and which are seen at the end of our plate, are, as it were, the heart of his steam apparatus, the lower pipes of the boiler are the arteries, and the upper pipes the veins. The water, which is the substitute for blood, is first sent from the reservoirs into the pipes—the operation of fire soon produces steam, which ascends through the pipes to the upper part of the reservoir, carrying with it a portion of water into the separators, which of course descends to the lower part, and returns to fill the pipes which have been exhausted by the evaporation of the steam—the steam above pressing it down with an elastic force, so as to keep the arteries or pipes constantly full, and preserve a regular circulation. In the centre of the separators are perforated steam pipes, which ascend nearly to the tops, these tops being of course closed, so as to prevent the escape of the steam. Through these pipes the steam descends with its customary force, and is conducted by one main pipe all along under the carriage to the end of the platform, which is, in point of fact, the water tank, where it turns under till it reaches two large branch pipes which communicate with the cylinders, from which the pistons move and give motion to the machinery. The cranks of the axle are thus set in action, and the rotatory movement is given to the wheels. By the power thus engendered also a pump is worked, and which, by means of a flexible hose, pumps the water into the boiler, keeping the supply complete. The tank and furnace, it is calculated will hold sufficient water and fuel for one hour's consumption, the former being sixty gallons."

The vehicle resembles the ordinary stage-coaches, but is rather larger and higher. Coke or charcoal are to form the fuel, by which means smoke will be avoided; the flues will be above the level of the seated passenger, and it is calculated that the motion of the carriage will always disperse the heated rarefied air from the flues.

The present carriage would carry six inside and fifteen outside passengers, independent of the guide, who is also the engineer. In front of the coach is a very capacious boot; while behind, that which assumes the appearance of a boot is the case for the boiler and the furnace. The length of the vehicle, from end to end, is fifteen feet, and, with the pole and pilot-wheels, twenty feet. The diameter of the hind wheels is five feet; of the front wheels three feet nine inches; and of the pilot-wheels three feet. There is a treble perch, by which the machinery is supported, and beneath which two propellers, in going up a hill, may be set in motion, somewhat similar to the action of a horse's legs under similar circumstances. In descending a hill, there is a break fixed on the hind wheel to increase the friction; but independent of this, the guide has the power of lessening the force of the steam to any extent, by means of the lever to his right hand, which operates upon, what is called the throttle valve, and by which he may stop the action of the steam altogether, and effect a counter vacuum in the cylinders. By this means also he regulates the rate of progress on the road, going at a pace of two miles or ten miles per hour, or even quicker if necessary. There is another lever also by which he can stop the vehicle instanter, and, in fact, in a moment reverse the motion of the wheels, so as to prevent accident, as is the practice with the paddles of steam-vessels. The guide, who sits in front, keeps the vehicle in its proper course, by means of the pilot-wheels acting upon the pole, like the handle of a garden-chair.

The weight of the carriage and its apparatus is estimated at 1-1/2 tons, and its wear and tear of the road, as compared with a carriage drawn by four horses, is as one to six. When the carriage is in progress the machinery is not heard, nor is there so much vibration as in an ordinary vehicle, from the superior solidity of the structure. The engine has a twelve-horse power, but may be increased to sixteen; while the actual power in use, except in ascending a hill, is but eight-horse.

The success of the present improved invention is stated to be decided; but the public will shortly have an opportunity of judging for themselves, as several experimental journeys are projected. If it should attain its anticipated perfection, the contrivance will indeed be a proud triumph of human ingenuity, which, aided by its economy, will doubtless recommend it to universal patronage. Mr. Gurney has already secured a patent for his invention; and he has our best wishes for his permanent success.

HISTORICAL FACTS RELATIVE TO THE EARLY CONDITION OF THE ENGLISH

London, in early times (King Ethelred's reign) consisted only of scattered buildings from Ludgate to Westminster, and none where the heart of the city now is; it was afterwards extended more westward and continued increasing–eastward being neglected until a more later period. Who can view its present well constructed houses, its numerous elegant squares and terraces, and its general superior appearance, without almost doubting that the inhabitants of Britain once dwelt in the most miserable habitations, regardless in every respect of comfort and cleanliness. Indeed, at an early period we seem to have been in a very wretched condition. Without carrying ourselves too far back, we will look at the state of the English about the year 1520, (Henry the Eighth's reign.) The houses were built entirely regardless of all that health and comfort could suggest. The situation of the doors and windows was never thought of, and the former only opened. The floors were made either of clay, or sand, covered with rushes, which were very seldom removed.1 Some few houses were built of stone, but generally they were composed of wood, coated over with mud, or cement, with straw or reed roofs. Things seem to have been in no very enviable condition during this reign. The laws were little obeyed; thefts and robbery were frequent, for "22,000 criminals are said to have been executed by the rigid justice of Henry VIII."

It is not surprising that crime should have been great in this reign, for Henry himself was not only guilty of many crimes, but patronised vice in the regular system of bull and bear-baiting, particularly on Sundays, about four in the afternoon, which exhibitions were attended by great crowds of persons of all classes. The accommodations of a royal establishment at this period are thus described:—"The apartments at Hampton Court had been furnished on a particular occasion, each with a candlestick, a basin, goblet and ewer of silver; yet the furniture of Henry's chamber, independent of the bed and cupboard, consisted only of a joint-stool, a pair of andirons, and a small mirror. The halls and chambers of the wealthy were replenished with a cupboard, long tables, or rather loose boards placed upon tressels, forms, a chair, and a few joint-stools. Carpets were only employed to garnish cupboards." The food in this reign appears to be in character with everything else. From a household book of the Earl of Northumberland, it appears that his family, during the winter, fed mostly on salt meat and salt fish, with "an appointment of 160 gallons of mustard." On flesh days through the year, breakfast for my lord and lady was a loaf of bread, two manchets, a quart of beer, a quart of wine, half a chine of mutton, or a chine of beef, boiled. The earl had only two cooks to dress victuals for more than two hundred people. Hens, chickens, and partridges, were reckoned delicacies, and were forbidden except at my lord's table.

This excessive love for eating was not, however, confined to Henry's time, for about two centuries previous to this, (Edward III.) feasting was endeavoured to be restrained by a law, though Edward himself did not follow his own law, for when his "son, Lionel, of Clarence, married Violentes, of Milant there were thirty courses, and the fragments fed 1,500 persons."

The formation of London was but tardy and very irregular until the reign of Henry VIII. at which time, some extensive buildings and improvements were made. On the other hand, building seems at length to have gone on too rapidly, and caused such alarm, that about a century after Henry's reign, a proclamation was issued by James I. after mature deliberation, forbidding all new buildings within ten miles of London; and commanding if any were built after this they should be pulled down, though no notice was taken of them for seven years.

It is somewhat singular, that though the population in these early days were but a handful in comparison to the present number, the redundancy of population was as bitterly complained of as it ever has been in modern days. About thirty years after Henry's reign (Elizabeth) we learn from one Harrison, who wrote in 1577, that "a great number complain of the increase of povertie, laying the cause upon God, as though he were in fault for sending such increase of people, or want of wars that should consume them, affirming that the land was never so full. Some affirming that youth by marrying too soon do nothing to profit the countrie; but fill it full of beggars, to the hurte and utter undooing, they say, of the common wealth. The better minded doo forsake the realme for altogether, complaining of no room to be left for them at home." If there was no room in Elizabeth's time, what must be our present situation? Indeed the present crowded state of the metropolis, and the general closeness of the buildings, has frequently been a subject for regret, as tending to render it unhealthy and impure; but on referring to its state, when in comparison it was but a village, the old writers state that in the city, and all round it were a great number of pits and ditches, and sloughs, which were made the receptacle of all kind of filth, dead and putrid horses, and cattle, &c. In the time of Henry VIII. many parts are described as "exceedingly foul and full of pits and sloughs, and very noisome," and some years after (1625) in a tract, the author says, "Let not carkasses of horses, dogs, cats, &c. lye rotting and poisoning the aire, as they have done in More and Finsbury Fields, and elsewhere round about the cittie. Let the ditches towards Islington, Olde-street, and towards Shoreditch and Whitechapel, be well cleansed." In another tract published in 1665, it states, that "there are all sorts of unsavoury stenches, proceeding either from carrion, ditches, rotten dung-hills, vaults, sinks, nasty kennels, and streets, (strewed with all manner of filth) seldom cleansed." From these statements it is evident that notwithstanding all the present inconveniences that the inhabitants of London live in more healthy situations now that they are surrounded by houses, than when they were exposed to extensive open fields.

A.B.CA PORTRAIT

Sketched in the year of the world, 5831; and, of my bachelorship, 24(For the Mirror.)Chaste, as the icicle,That's curded by the frost from purer snow,And hangs on Dian's temple; Dear—old maid.SHAKSPEARE'S Coriolanus.Sed mihi vel tellus optem prius ima dehiscat,Vel Pater omnipotens adigat me fulmine ad umbras,Pallentes umbras Erebi, noctemque profundum,Ante, pudor, quam te violem, aut tua jure resolvam.VIRGIL.I have years on my back forty-eight,SHAKSPEARE'S King Lear.Four-and-twenty lap-dogs, all of a row,Four-and-twenty monkeys, kits, and cats, dit-to;Four-and-twenty colours in her tawdry dress,(A rainbow she in all—but its loveliness!)Four-and-twenty tempers, in the four-and-twenty hours;Four-and-twenty dreams of suppos'd vanquished pow'rs,To wit of four-and-twenty swains—more or less;Who have four-and-twenty times, curs'd her ugliness!Four-and-twenty trials, ere as many hours are o'er,Of four-and-twenty genera of rival Kalydor;Four-and-twenty scentings with her dear bergamot,Four-and-twenty daubs of her dear paint-pot;Four-and-twenty visitings to four-and-twenty friends,And four-and-twenty tales of 'em, before the day ends;Of these said four-and-twenty tales just four-and-twenty versions,And all of them of all the facts most farcica perversions.Four-and-twenty false curls, * *Four-and-twenty false teeth, and quite as false a tongue,Which tells how virtuous was the world when—she and it were young.Or rather for these thirty years has moralizing told,How this good deed and that she'll do, before she grows old:Four-and-twenty sighs a-day, that our rude English skyIs not precise as she—and may wash off the dyeMeretricious of her cheeks, which are then like gold,(Though less tempting;) sweet and yellow as a marigold!2Four-and-twenty wailings o'er the wedded state,Yet twice as many every day 'tis not her fate;Pretending to the world 'tis mere choice that has ledTo singleness—yet choosing all the while to be wed,If any doting fool could be doting fool enoughTo bid for such a breaking down piece of stuff;For any such a winter, that has shed the flowers of spring,Whose autumn too is flown; nor left its fruit or any thing!Yes, such are the marks deep branded on a classOf busy blanks, non-entities, creation's very farce;In these scales then be every piece of Eve's flesh weighed,Find these criteria, and be sure you've found an—Ancient Maid!W. P–NANECDOTES, ROYAL AND NOBLE

(For the Mirror.)James the FirstRobert Cecil, great grandson to the first Earl of Salisbury, told Lord Dartmouth that his ancestor, inquiring into the character of king James, Bruce (his majesty's own ambassador) answered, "Ken ye a John Ape? en I's have him, he'll bite you; en you's have him, he'll bite me."

Sir Edward SeymourSpeaker of the House of Commons, was one day coming to his duty, when his coach happening to break down, he ordered the beadle to stop the first gentleman's coach they met, and bring it to him. The owner felt much surprised to be turned out of his own coach; but Sir Edward told him it was much more proper for him to walk in the streets than the speaker of the House of Commons; and accordingly left him to do so without farther apology.—This arbitrary exercise of authority is perhaps without a parallel.

Henry the FourthOf France used to say that a king should have the heart of a child towards God, but the heart of a father towards his subjects.

George the ThirdHis late majesty was very partial to Mr. Carbonel, the wine-merchant, and frequently admitted him to the royal hunts. Returning from the chase one day, the king entered affably into conversation with his wine-merchant, and rode with him side by side a considerable distance. Lord Walsingham was in attendance, and watching an opportunity, called Mr. C. aside, and whispered something to him. "What's that? what has Walsingham been saying to you?" inquired the good-humoured monarch. "I find, sire, I have been unintentionally guilty of disrespect by not taking off my hat when I address your majesty; but you will please to observe, that whenever I hunt my hat is fastened to my wig, and my wig to my head; and as I am mounted on a very spirited horse, if any thing goes off, we must all go off together." The king laughed heartily at the whimsical apology.

The Duke of WellingtonA certain noble lord, who was the duke's aide-de-camp, visited his grace early on the morning of the battle of Salamanca, and perceiving him lying on a very small camp bedstead, observed, "that his grace had not room to turn himself;" who immediately, in his usual characteristic manner, rejoined, "When you have lived as long and seen so much as I have, you will know, that when a general thinks of turning in his bed, it is full time to turn out."

RubensAn artist named Brendel, possessed with the folly of the "philosopher's stone," proposed to Rubens to join him in the discovery of that mystery. He replied, "Your application is too late; for these twenty years past my pencils and pallet have revealed to me the secret about which you are so anxious."

Queen ElizabethWhen the ambassador of Henry IV. of France was in England, the queen asked him one birth-night, which was attended by a splendid assembly of the court, how he liked her ladies. Knowing her majesty was not averse to flattery, he made the following elegant reply: "It is hard, madam, to judge of stars in the presence of the sun."

Louis XIIIWas remarkable in his youth for piety; entering a little village, the better sort of inhabitants wished to attend him with a canopy. He answered, "I hear you have no church here. I cannot suffer a canopy of state to be borne over my head in a place where God hath not a consecrated roof to dwell under."

SigismundEmperor of Germany, being once asked what was the surest method of living happy in the world, replied, "By doing in health those good works you promised to do on the bed of sickness."

JACOBUSARCANA OF SCIENCE

Thunder and LightningConductors affixed to houses should always be pointed, and the point should be kept in a state of cleanliness, and the conductors should terminate in a moist stratum of earth, or in London it might safely be conveyed into the common sewer. It has been objected to the use of pointed conductors, that we invite the lightning to the point; and that is true to a certain extent, and in gunpowder mills the conductor should be placed at some distance from the building. The conducting rod should be of copper or iron, and from half to three-fourths of an inch in diameter, so as not to be readily forced. Its upper end should be elevated about three or four feet above the highest part of the building, and all the metallic parts of the roof should be connected with the rod, which should be continuous throughout. As regards the question of what is the safest situation in a thunder-storm, we should be pretty safe in the middle of a large room in bed; we should be pretty safe among the feathers, which are bad conductors; but as the bell-wires will conduct the electricity into the room, the bed should be removed from them. It would be well to stand at a distance from the chimney on a woollen rug, which is a non-conductor. When out of doors, I scarcely need to say, that you should never stand under a tree; the tree being moist, the electric fluid generally passes down between the bark and the substance of the tree, splitting it in all directions, and the lightning will pass to the best conductor near it; if any unfortunate animal should happen to be under the tree, it will be killed. The safest plan is to go toward the middle of the field, at a distance from any tree, and to stretch yourself out upon the ground, although this is not a very pleasant situation, especially in hard rain. During a thunder-storm, the earth is in a state of electricity as well as the clouds, and the light and heat which are produced at the explosion indicate the annihilation of the two electricities. Sometimes the discharge is only from cloud to cloud, sometimes from the earth to the clouds, and sometimes from the clouds to the earth, as one or other may be in the positive or negative state. The clouds are usually more or less electrical when the vapour, floating about in the atmosphere, is condensed, and the earth being brought into an opposite state of electricity by induction, a discharge takes place, when the clouds approach within a certain distance, and sometimes the electric cloud perches upon a hill, and then discharges itself. The electricity passes through the clouds in a zig-zag direction, and the undulation of the air which it produces is the cause of the noise which we hear, called thunder, which is more or less intense, and of longer or shorter duration, according to the quantity of air acted upon, and the distance of the place where the report is heard from the point of discharge. If the danger be great, we have seldom any opportunity to count the time which elapses between the appearance of the lightning and the report: electrical effects take place at no sensible time; it has been found, that a discharge through a circuit of four miles is instantaneous, whilst sound moves at the rate of about twelve miles in a minute. So that, supposing the lightning to pass through a space of some miles, the explosion will be first heard from the point of the air agitated nearest to the spectator; it will gradually come from the more remote parts of the course of the electricity, and, last of all, will be heard from the very extremity; and the different degrees of the agitation of the air, and the difference of the distance, will account for the different intensities of the sound, and its apparent reverberations and changes. If you can count from two to three seconds between the appearance of the lightning and the sound, there is seldom much danger; and when the interval is a quarter of a minute, you are secure.—Brande's Lectures.—Lancet.