Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 281, November 3, 1827

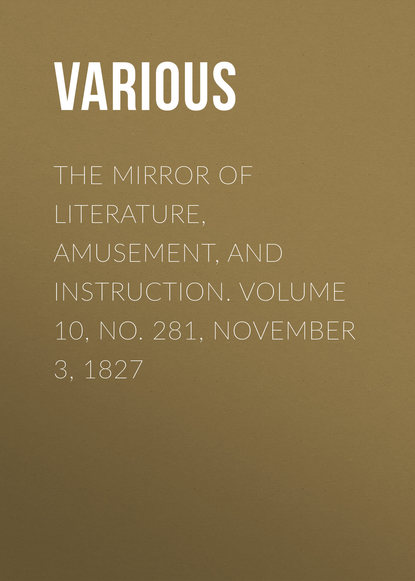

Of the suicides of these three years 25, 50, and 36, were attributed to love, and 52, 42, 43, to despair arising from gaming, the lottery, &c. In the winter of 1826, several exaggerated losses by gaming were circulated in Paris with great finesse, to enable bankrupts to account for their deficiencies, many of whom were exposed and deservedly punished.

A few words on the prevention of gaming, the consideration of which gave rise to this hasty sketch; I mean by dramatic exhibitions of its direful effects. On our stage we have a pathetic tragedy by E. Moore, which, though seldom acted, is a fine domestic moral to old and young; but the author

"Was his own Beverley, a dupe to play."It is scarcely necessary to allude to the recent transfers of a celebrated French exposé of French gambling to our English stage, otherwise than to question their moral tendency. The pathos of our Gamester may reach the heart; but the French pieces command no such appeal to our sympathies. On the contrary, the vice is emblazoned in such romantic and fitful fancies, that their effect is questionable, especially on the majority of those who flock to such exhibitions. The extasies of the gamester are too seductive to be heightened by dramatic effect; neither are they counterbalanced by their consesequent misery, when the aim of these representations should be to outweigh them; for the authenticated publication of a single prize in the lottery has been known to seduce more adventurers than a thousand losses have deterred from risk. But they keep up the dancing spirits of the multitude, and it will be well if their influence extends no further.

PHILO.A RETROSPECT

Oh, when I was a tiny boy,My days and nights were full of joy; My mates were blithe and kind!—No wonder that I sometimes sigh,And dash the tear-drop from my eye. To cast a look behind!A hoop was an eternal roundOf pleasure. In those days I found A top a joyous thing;—But now those past delights I drop;My head alas! is all my top, And careful thoughts the string!My marbles—once my bag was stor'd,—Now I must play with Elgin's lord,— With Theseus for a taw!My playful horse has slipt his string.Forgotten all his capering, And harness'd to the law!My kite—how fast and fair it flew.Whilst I, a sort of Franklin, drew My pleasure from the sky!'Twas paper'd o'er with studious themes,—The tasks I wrote—my present dreams Will never soar so high!My joys are wingless all, and dead;My dumps are made of more than lead; My flights soon find a fall;My fears prevail, my fancies droop,Joy never cometh with a hoop, And seldom with a call!My football's laid upon the shelf;I am a shuttlecock, myself The world knocks to and fro;—My archery is all unlearn'd,And grief against myself has turn'd My sorrow and my bow!No more in noontide sun I bask;My authorship's an endless task, My head's ne'er out of school;My heart is pain'd with scorn and slight;I have too many foes to fight, And friends grown strangely cool!The very chum that shar'd my cakeHolds out so cold a hand to shake, It makes me shrink and sigh:—On this I will not dwell and hang,The changeling would not feel a pang Though these should meet his eye!No skies so blue or so sereneAs these;—no leaves look half so green As cloth'd the play-ground tree!All things I lov'd are altered so,Nor does it ease my heart to know That change resides in me.O, for the garb that mark'd the boy!The trousers made of corduroy. Well ink'd with black and red;The crownless hat, ne'er deem'd an ill—It only let the sunshine still Repose upon my head!O, for that small, small beer anew!And (heaven's own type) that mild sky-blue That wash'd my sweet meals down!The master even!—and that small turkThat fagg'd me!—worse is now my work,— A fag; for all the town!The "Arabian Nights'" rehears'd in bed!The "Fairy Tales" in school-time read By stealth, 'twixt verb and noun!The angel form that always walk'dIn all my dreams, and look'd, and talk'd. Exactly like Miss Brown!The omne bene—Christmas come!The prize of merit, won for home'— Merit had prizes then!But now I write for days and daysFor fame—a deal of empty praise, Without the silver pen.Then home, sweet home! the crowded coach—The joyous shout—the loud approach— The winding horn like ram's!The meeting sweet that made me thrill,The sweetmeats almost sweeter still, No "satis" to the "jams!"ENGLISH DRESS

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)Mr. Editor.—In No. 200 of the MIRROR, you will find an article, entitled Female Fashions during the early part of the Last Century. The author then promised to give a description of the dress of the English gentlemen of the same period, but as no such description has yet appeared in your pages, I trust you will insert the annexed at your first convenient opportunity.

G.W.N.Dress of the English Gentlemen during the Early part of the Last CenturyIn the reign of King William III., the English gentlemen affected to dress like their dependents. Their hats were laced, and their coats and waistcoats were embroidered with gold and silver fringe; indeed it really became extremely difficult to distinguish a man of quality from one of his lackeys. They did not, however, long persevere in this ridiculous imitation, for they soon afterwards, like the ladies, servilely followed the French fashions. The great partiality of the English beau monde towards the bon ton of France, was a wonderful advantage to that country—an advantage which the English government in vain endeavoured to abolish, although a heavy duty was imposed on all French ribbon and lace imported into this kingdom. Many millions were annually expended in French cambric, muslin, ribbon, and lace, which useless expenditure very sensibly injured our commercial transactions with other nations.

Perukes and long wigs were worn at the revolution; but these being greatly inconvenient in all weathers, some people tied up their wigs, which was the first occasion of short wigs coming into fashion. Some few years afterwards, bob-wigs were adopted by the gentlemen, especially by those of the army and the navy.

The English costume was remarkably neat and plain anterior to the year 1748; at which period, however, all gentlemen rather resembled military officers than private individuals, for their coats were not only richly embroidered with gold and silver, but they even assumed the cockade in their hats, and carried long rapiers at their sides. At length this imposing attire was adopted by the merchants and tradesmen of the metropolis, and soon afterwards by the most notorious rogues and pickpockets in town, so that when any person with a laced coat, a cockade, and a sword, walked along the streets of London, it was absolutely impossible to determine whether he affected to be thought a nobleman, a military officer, a tradesman, or a pickpocket, for he bore an equal resemblance to each of these characters.

In the year 1749, hair-powder was used by the finished gentlemen, though the use of it, a year or two previous, was prohibited in every class of society. Of the costume of this period (i.e. about 1749), the immortal Hogarth, in his works, has left us numerous specimens, which need no comment here: his productions, indeed, are so equal in merit, that it is impossible to decide which is his ne plus ultra.

In conclusion, I would advise the reader to refer to a few of Hogarth's prints, for they will admirably serve to illustrate the above observations on the fashions and habits of our forefathers.

Astronomical Occurrences

FOR NOVEMBER, 1827

(For the Mirror.)Should the afternoon of Saturday, the 3rd of the month, prove favourable, we shall be afforded an opportunity of witnessing another of those interesting phenomena—eclipses, at least the latter part of one, a portion of it only being visible to the inhabitants of this island; the defect above alluded to is a lunar one. The passage of the moon through the earth's shadow commences at 3 h. 29 m. 34 s. afternoon; she rises at Greenwich at 4 h. 45 m. 34 s. with the northern part of her disk darkened to the extent of nearly 10 digits. The greatest obscuration will take place at 5 h. 7 m. 42 s. when 10½ digits will be eclipsed; she then recedes from the earth's shadow, when the sun's light will first be perceived extending itself on her lower limb towards the east; it will gradually increase till she entirely emerges from her veil of darkness, the extreme verge of which leaves her at her upper limb 32 deg. from her vertex, or highest point of her disc.

We have the following in "Moore," some years ago, on the nature and causes of eclipses of the sun and moon:—

"Far different sun's and moon's eclipses are,The moon's are often, but the sun's more rareThe moon's do much deface her beauty bright;Sol's do not his, but hide from us his sight:It is the earth the moon's defect procures,'Tis the moon's shadow that the sun obscures.Eastward, moon's front beginneth first to lack,Westward, sun's brows begin their mourning black:Moon's eclipses come when she most glorious shines,Sun's in moon's wane, when beauty most declines;Moon's general, towards heaven and earth together,Sun's but to earth, nor to all places neither."The Sun enters Sagittarius on the 23rd, at 1 h. 2 m. morning.

Mercury will be visible on the 10th, in 10 deg. of Sagittarius, a little after sunset, being then at his greatest eastern elongation; he is stationary on the 20th, and passes his inferior conjunction on the 30th, at 1¾ h. afternoon.

Venus is in conjunction with the above planet on the 24th, at 9 h. evening; she sets on the 1st at 5 h. 7 m., and on the 30th at 4 h. 47 m. evening.

Jupiter may be seen before sunrise making his appearance above the horizon about 5 h.; he is not yet distant enough from the sun to render the eclipses of his satellites visible to us.

A small comet has just been discovered, situated in one of the feet of Cassiopea. It is invisible to the naked eye, and appears approaching the pole with great rapidity.

PASCHE.RETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS

DOMESTIC ECONOMY OF THE ROMANS IN THE FOURTH CENTURY

A recent discovery has added to our information the most extensive series of statistical data, which make known from an official act, and by numerical figures, the state of the Roman empire 1500 years ago; the price of agricultural and ordinary labour; the relative value of money; the abundance or scarcity of certain natural productions; the use, more or less common, of particular sorts of food; the multiplication of cattle and of flocks; the progress of horticulture; the abundance of vineyards of various qualities; the common use of singular meats, and dishes, which we think betrays a corruption of taste; in short the relation of the value existing between the productions of agriculture and those of industry, from whence we obtain a proof of the degree of prosperity which both had reached at this remote period.

This precious archaeological monument is an edict of Diocletian, published in the year 303 of our era, and fixing the price of labour and of food in the Roman empire. The first part of this edict was found by Mr. William Hanks, written upon a table of stone, which he discovered at Stratonice, now called Eskihissar in Asia Minor. The second part, which was in the possession of a traveller lately returned from the Levant, has been, brought from Rome to London by M. de Vescovali, and Colonel Leake intends to publish a literal translation of it. This agreement of so many persons of respectable character, and known talents, excludes all doubts respecting the authenticity of the monument.

The imperial edict of Diocletian is composed of more than twenty-four articles. It is quite distinct from that delivered the preceding year for taxing the price of corn in the eastern provinces, and it contained no law upon the value of corn. It fixed for all the articles which it enumerated a maximum, which was the price in times of scarcity. For all the established prices it makes use of the Roman Denarii; and it applies them to the sextarius for liquids, and to the Roman pound for the things sold by weight.

Before the Augustan age, the denarius was equal to eighteen sous of our money; but it diminished gradually in value, and under Diocletian its value was not above nine sous of French money, and 45 centimes. The Roman pound was equivalent to 12 ounces, and the sextarius which was the sixth part of a conge, came near to the old Paris chopin, or half a litre.

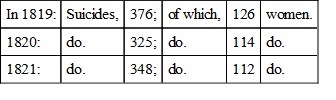

Proceeding on these data, M. Moreau de Jonnes has formed a table, showing, 1. the maximum in Roman measures, the same as the established imperial edict; and 2. the mean price of objects formed from half the maximum, and reduced into French measures.

The following is the table drawn up by M. Moreau de Jonnes. The slightest inspection of it will enable us to appreciate the importance of this archaeological discovery, for no monument of antiquity has furnished so long a series of numerical terms, of statistical data, and positive testimony of the civil life and domestic economy of the Greeks and Romans:—

We are much surprised at the very high prices in this table. Labour and provisions cost ten and twenty times as much as with us. But when we come to compare the price of provisions with the price of labour the dearness of all the necessaries of life appears still more excessive. M. Moreau de Jonnes makes this comparison. He brings together from the edicts of Diocletian a great many facts given by historians, and he shows, that, if the abundance of the precious metals has any influence on raising the prices, the want of labour, industry, and of produce, must cause it also.

These considerations point out in the strongest manner the poverty of this royal people, of whom two-thirds, if not three-fourths, were reduced to live on fish and cheese, and drink piquette, when the expense of the table of Vitellius amounted, in a single year, to 175 millions of Francs.—Brewster's Journal of Science.

THE GATHERER

"I am but a Gatherer and disposer of other men's stuff."

—WottonTWELVE GOLDEN RULES OF CHARLES I

1. Profane no divine ordinances. 2. Touch no state matters. 3. Urge no healths. 4. Pick no quarrels. 5. Maintain no ill opinions. 6. Encourage no vice. 7. Repeat no grievances. 8. Reveal no secrets. 9. Make no comparisons. 10. Keep no bad company. 11. Make no long meals. 12. Lay no wagers.

EPIGRAMS,

Written on the Union, 1801, by a celebrated Barrister of Dublin Adapted to the Commercial Failures, 1800Why should we exclaim, that the times are so bad,Pursuing a querulous strain?When Erin gives up all the rights that she had,What right has she left to complain?The Cit complains to all he meets,That grass will grow in Dublin streets,And swears that all is over!Short-sighted mortals, can't you see,Your mourning will be chang'd to glee—For then you'll live in clover.Necessitas non habet legemON SIR JOHN ANSTRUTHER

By the Honourable Thomas ErskineNecessity and Law are alike each other:Necessity has no Law—nor has Anstruther.EPITAPH ON A CONTROVERSIALIST

On the death of that turbulent and refractory enthusiast, John Lilburne, alias Free-born John, alias Lilburne the Trouble-world, there appeared the following epigrammatic epitaph:—

Is John departed, and is Lilburne gone?Farewell to both, to Lilburne and to John!Yet being gone, take this advice from me,Let them not both in one grave buried be.Here lay ye John; lay Lilburne thereabout,For if they both should meet, they would fall out.This alluded to a saying, that John Lilburne was so quarrelsome, that if he were the only man in the world, John would quarrel with Lilburne, and Lilburne with John. Lilburne, it will be remembered, was a sad thorn in Cromwell's sore side, for which the protector amply repaid him.

HOSPITAL OF SURGERY

A new surgical hospital is to be forthwith erected in the neighbourhood of Charing Cross, where the King, with his usual and characteristic munificence, has given a spot of ground on which it is to be erected. A benevolent individual has given, within these few days, 1,500l. towards a fund for the building.

Printed and Published by J. Limbird, 143, Strand, (near Somerset House,) and sold by all Newssmen and Booksellers.

1

As the Palais Royal may be considered the central point of the maisons de jeu, or gambling-houses, it will not be irrelevant to give a brief sketch of them:—

The apartments which they occupy are on the first floor, and are very spacious. Upon ascending the staircase is an antechamber, in which are persons called bouledogues (bull-dogs), whose office it is to prevent the entrance of certain marked individuals. In the same room are men to receive hats, umbrellas, &c., who give a number, which is restored upon going out.

The antechamber leads to the several gaming rooms, furnished with tables, round which are seated the individuals playing, called pontes (punters), each of whom is furnished with a card and a pin to mark the rouge and noir, or the number, in order to regulate his game. At each end of the table is a man called bout de table, who pushes up to the bank the money lost. In the middle of the table is the man who draws the cards. These persons, under the reign of Louis XIV., were called coupeurs de bourses (purse-cutters); they are now denominated tailleurs. After having drawn the cards, they mate known the result as follows:—Rouge gagne et couleur perd.—Rouge perd et couleur gagne.

At roulette, the tailleurs are those who put the ball in motion and announce the result.

At passe-dix, every time the dice are thrown, the tailleurs announce how many the person playing has gained.

Opposite the tailleur, and on his right and left, are persons called croupiers, whose business it is to pay and to collect money.

Behind the tailleurs and croupiers are inspectors, to see that too much is not given in payment, besides an indefinite number of secret inspectors, who are only known to the proprietors. There are also maîtres de maison, who are called to decide disputes; and messieurs de la chambre, who furnish cards to the pontes, and serve them with beer, &c., which is to be had gratis. Moreover, there is a grand maître, to whom the apartments, tables, &c., belong.

When a stranger enters these apartments, he will soon find near him some obliging men of mature age, who, with an air of prudence and sagacity, proffer their advice. As these advisers perfectly understand their own game, if their protégés lose, the mentors vanish; but it they win, the counsellor comes nearer, congratulates the happy player, insinuates that it was by following his advice that fortune smiled on him, and finally succeeds in borrowing a small sum of money on honour. Many of these loungers have no other mode of living.

There is likewise another room, furnished with sofas, called chamber des blessés, which is far from being the most thinly peopled.

The bank pays in ready money every successful stake and sweeps off the losings with wooden instruments, called rateaux (rakes).

It was in one of the houses in this quarter that the late Marshal Blucher won and lost very heavy sums, during the occupation of Paris by the allied armies.

There are two gaming-houses in Paris of a more splendid description than those of the Palais Royal, where dinners or suppers are given, and where ladies are admitted.—Galignani's History of Paris.