Полная версия

Полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 272, September 8, 1827

STANZAS

(For the Mirror.)Oh! poverty, thou tyrant of the mind,How eager would I shun thy cold embrace,And try some hospitable shore to find!Some welcome refuge; some more happy place.But ah! the stars shone adverse at my birth,Tho' boyish pleasures all my youth beguil'd,And little thought amidst those scenes of mirth,That I was doom'd to be misfortune's child.At last the haggard wretch is come; and I,Like some poor hark, toss'd by the mighty wave,Am solitary left, nor have wherewith to flyHer dread embrace, save to man's friend—the grave.No hope, alas! possesses now my mind,Plung'd in the deepest gulf of penury;No earthly friend, to pity none inclined;To soothe the bitter pang of misery.'Tis hope that raises us to heaven,While pure affection breathes no other love,And makes to those to whom it's givenA something like a paradise above.Alas! for me no earthly paradise awaits;No true affection nor no friendly tear;Spurn'd at by friends, and scorned at by the great;And all that poverty can bring is here.Then hail thou grateful visitant, oh death,And stop the troubled ocean of my breast:Lull the rude waves; nor let my parting breathE'er cause a sigh, or break one moment's rest.Then when my clay-cold form shall bid adieu,Hid in its parent's bosom, kindred earth,Let not the errors e'er appear in view,But turn from them, and only speak his worth.J.ATHE SKETCH BOOK

THE CONVERSATION OF ACTORS

Actors are rather generally esteemed to be what is commonly called "good company." For our part, we think the companionable qualities of the members of the corps drámatique are much overrated. There are many of them, we know full well, as pleasant and agreeable spirits as any extant; but the great mass of actors are too outrageously professional to please. Their conversation is too much tainted with theatricals—they do not travel off the stage in their discourse—their gossip smacks of the green-room—their jests and good things are, for the most part, extracts from plays—they lack originality—the drama is their world, and they think nothing worthy of argument but men and matters connected with it. They are the weakest of all critics, their observations on characters in plays are hereditary opinions of the corps, which descend as heir looms with the part to its successive representatives. There are, doubtless, some splendid exceptions—we could name several performers, who talk finely on general subjects, who are not confined to the foot-lights in their fancies, who utter jests of the first water, whose sayings are worth hearing, and whose anecdotes are made up of such good materials, and are so well told withal, that our "lungs have crowed like chanticleer" to hear them. Others, we have met with, who are the antipodes of those drama-doating gentlemen whom we have noticed above, who rarely, unless purposely inveigled into it, mention the stage or those who tread it. One highly gifted individual, when alive, enjoyed a discourse on the merits of Molyneux, the small talk of the P.C., or a vivid description of an old-school fight; another has a keen relish for all matters connected with the Great St. Ledger—the state of the odds against the outside fillies for the Oaks—the report of those deep versed in veterinary lore, upon the cough of the favourite for the Derby; you cannot please a certain excellent melo-dramatic actor better than by placing him alongside of an enthusiastic young sailor, who will talk with him about maintops and mizens—sky-scrapers and shrouds—

of gallant ships,Proudly floating o'er the dark blue ocean.The eternal theme of one old gentleman is his parrot, and another chatters incessantly about his pupils. Some of the singers—the serious order of singers—are as namby-pamby off the stage as they are on it, unless revelling in "sweet sounds;" they are too fond of humming tunes, solfaing, and rehearsing graces in society; they have plenty to sing, but nothing to say for themselves; they chime the quarters like "our grandmother's clock," and at every revolution of the minute index, strike up their favourite tune. This is as bad as being half-smothered in honey, or nearly

Washed to death in fulsome wine.There is one actor on the stage who is ever attempting to show the possibility of achieving impossibilities; he is one of the most pleasant visionaries in existence; his spirit soars aloft from every-day matters, and delights in shadowy mysteries; a matter-of-fact is a gorgon to him; he abhors the palpable, and doats upon the occult and intangible; he loves to speculate on the doings of those in the dogstar, to discuss on immortal essences, to dispute with the disbeliever on gnomes—a paradox will be the darling of his bosom for a month, and a good chimera be his bedfellow by night and theme by day for a year. He is fickle, and casts off his menial mistress at an hour's notice—his mind never weds any of the strange, fantastic idealities, which he woos for a time so passionately—deep disgust succeeds to the strongest attachment for them—he is as great a rake among the wayward "rebusses of the brain" which fall under his notice as that "wandering melodist—the bee of Hybla"—with the blossoms of spring. He has no affection for the schemes, or "vain imaginations" of other men—no one can ridicule them more smartly—he loves only "flowers of his own gathering"—he places them in his breast, and wears them there with miraculous constancy—flaunts them in the eyes of his friends—woos the applause, the admiration of every one at their charms—and the instant he discovers that another feels a budding fondness for their beauties, he dashes them from him, and abuses them for ever after, sans mercy.—Every Night Book.

FINE ARTS

THE WORKS OF CANOVA

(For the Mirror.)Canova, while living, was thought to be the first sculptor of the age, and his works are still greatly admired—for their exquisite finishing, and for their near resemblance to real life. They are certainly very attractive, and may be contemplated a considerable time with delight; but they never impose upon the beholder, and never raise in his mind any of those sublime ideas which he invariably experiences while contemplating the works of the ancients, or the modern productions of Michael Angelo Buonarotti. Canova, in fact, though he possessed the grace, the elegance, and the liveliness of the greatest masters of Italy, could never surmount a certain degree of littleness, which failure predominates in most of his works. The calm, tranquil, and dignified pathos of Leonardo di Vinci cannot be traced in Canova's countenances, which rather approach to those represented by Charles le Brun, Eustache le Seur, and other French artists. Though his men were generally deficient in dignity, the faces of his females were always pleasing, notwithstanding

"The sleepy eye, that spoke the melting soul,"peculiar to most Italian women, is never found in his productions. It does not appear likely that Canova, although his present admirers are very numerous, will be greatly idolized by posterity. Indeed, if we may be allowed to predict, his name, unlike that of his countryman, Buonarotti, will sink into oblivion. He, however, enjoyed a high reputation as an artist while he lived, and his sculpture is now eagerly sought for by the lovers of the fine arts, both in Great Britain, and on the continent.

Canova died at Venice, in the month of October, 1822. His death was heard with extreme regret in Europe, and indeed in all parts of the globe where his works were known.

G.W.NANECDOTES AND RECOLLECTIONS

THE COCK AFLOAT IN THE BOWL

Many attempts have been made to explain why the cock is sacred to Minerva; and his claims to her protection are often founded on an assumed preeminence of wisdom and sagacity. This brings to our mind a story related by a gentleman, late resident in the Netherlands, of a cock in a farm-yard somewhere in Holland, near Rotterdam, whose sagacity saved him from perishing in a flood, occasioned by the bursting of one of the dykes. The water rushing furiously and suddenly into the village, swamped every house to the height of the first story, so that the inhabitants were obliged to mount, and had no communication for awhile, except by boats. The cattle and other animals and many fowls perished. Our friend chanticleer, however, had the adroitness to jump into a large wooden bowl, containing some barley, in which he eat, and quietly floated, till the flood had subsided, having not only a good ship to carry him, but provision on board during his voyage.

Forster's Perennial CalendarGENERAL WOLFE

The minds of some men are so elevated above the common understanding of their fellow-creatures, that they are by many charged with enthusiasm, and even with madness. When George II. was once expressing his admiration of Wolfe, some one observed that the general was mad. "Oh! he is mad, is he?" said the king with great quickness; "then I wish he would bite some other of my generals."—Thackery's Life of the Earl of Chatham.

LORD ELLENBOROUGH

An amateur practitioner wishing upon one occasion, in the court of king's-bench, to convince Lord Ellenborough of his importance, said, "My lord, I sometimes employ myself as a doctor."—"Very likely, sir," said his lordship drily; "but is any body else fool enough to employ you in that capacity?"—Mems., Maxims, and Memoirs.

"FOUR THIEVES' VINEGAR."

A report of the plague in 1760 having been circulated, Messrs. Chandler and Smith, apothecaries, in Cheapside, had taken in a third partner, (Mr. Newsom,) and while the report prevailed, these gentlemen availed themselves of the popular opinion, and put a written notice in their windows of "Four Thieves' Vinegar sold here." Mr. Ball, an old apothecary, passing by, and observing this, went into the shop. "What," said he, "have you taken in another partner?"—"No."—"Oh! I beg your pardon," replied Ball, "I thought you had by the ticket in your window."—Ibid.

SNAKE EATING

To show the extreme desire of sailors for fresh animal food, towards the end of a long voyage, we may mention the following circumstance. A Dutch East Indiaman, after beating about for some time in the Indian ocean, became short of provisions. One day, as the crew were scrubbing the deck, a large sea-snake raised itself out of the water, and sprang or crawled aboard. The sailors, who for some time had not tasted any thing fresh, immediately despatched the snake, and, regardless of consequences, cooked and ate it for dinner—Weekly Review.

NEW SUSPENSION BRIDGE, HAMMERSMITH.

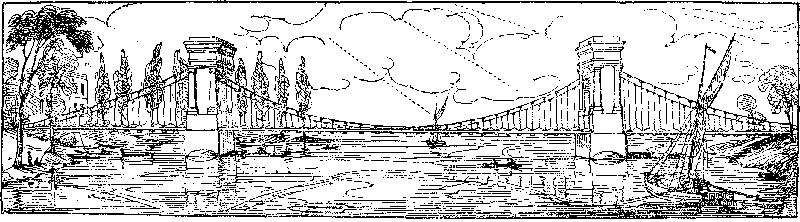

NEW SUSPENSION BRIDGE, HAMMERSMITH

To the many improvements which have already taken place in the neighbourhood of London, another will shortly be added; a suspension-bridge, intended to facilitate the communication between Hammersmith and Kingston, and other parts of Surrey. The clear water-way is 688 feet 8 inches. The suspension towers are 48 feet above the level of the roadway, where they are 22 feet thick. The roadway is slightly curved upwards and is 16 feet above high water, and the extreme length from the back of the piers on shore is 822 feet 8 inches, supporting 688 feet of roadway. There are eight chains, composed of wrought-iron bars, each five inches deep and one thick. Four of these have six bars in each chain; and four have only three, making thirty-six bars, which form a dip in the centre of about 29 feet. From these, vertical rods are suspended, which support the roadway, formed of strong-timbers covered with granite. The width of the carriageway is 20 feet, and footway five feet. The chains pass over the suspension towers, and are secured to the piers on each shore. The suspension towers are of stone, and designed as archways of the Tuscan order. The approaches are provided with octagonal lodges, or toll-houses, with appropriate lamps and parapet walls, terminating with stone pillars, surmounted with ornamental caps. The whole cost of this remarkable object, displaying the great superiority acquired by British artisans in the manufacture of ironwork, is about 80,000l. The advantages to be derived from this bridge in the saving of distance, will be a direct passage from Hammersmith to Barnes, East Sheen, and other parts of Surrey, without going over either Fulham or Kew bridges.

The annexed engraving may be consulted, in illustration of the foregoing remarks, as it is a correct and perfect delineation, having been taken from an original sketch made by our artist on the spot.

THE MONTHS

REAPING IN DEVONSHIRE

As an illustration of a prevailing harvesting custom, peculiar to more counties than one at this season, and at the opening of this month, we subjoin the following letter which appeared in vol. xxxvii. of the Monthly Magazine:—

The reaping and harvesting of the wheat is attended with so heavy an expense, and with practices of so disorderly a nature, as to call for the strongest mark of disapprobation, and their immediate discontinuance, or at least a modification of the pastime after the labours of the day. The wheat being ready to cut down, and amounting from ten to twenty acres; notice is given in the neighbourhood that a reaping is to be performed on a particular day, when, as the farmer may be more or less liked in the village, on the morning of the day appointed a gang, consisting of an indefinite number of men and women assemble at the field, and the reaping commences after breakfast, which is seldom over till between eight and nine o'clock. This company is open for additional hands to drop in at any time before the twelfth hour to partake of the frolic of the day. By eleven or twelve o'clock the ale or cider has so much warmed and elevated their spirits that their noisy jokes and ribaldry are heard to a considerable distance, and often serve to draw auxiliary force within the accustomed time. The dinner, consisting of the best meat and vegetables, is carried into the field between twelve and one o'clock; this is distributed with copious draughts of ale and cider, and by two o'clock the pastime of cutting and binding the wheat is resumed, and continued, without other interruption than the squabbles of the party, until about five o'clock; when what is called the drinkings are taken into the field, and under the shade of a hedge-row, or large tree, the panniers are examined, and buns, cakes, and all such articles are found as the confectionary skill of the farmer's wife could produce for gratifying the appetites of her customary guests at this season. After the drinkings are over, which generally consume from half to three quarters of an hour, and even longer, if such can be spared from the completion of the field, the amusement of the wheat harvest is continued, with such exertions as draw the reaping and binding of the field together with the close of the evening. This done, a small sheaf is bound up, and set upon the top of one of the ridges, when the reapers retiring to a certain distance, each throws his reap-hook at the sheaf, until one more fortunate, or less inebriated, than the rest strikes it down; this achievement is accompanied with the utmost stretch and power of the voices of the company, uttering words very indistinctly, but somewhat to this purpose—we ha in! we ha in! we ha in!—which noise and tumult continue about half an hour, when the company retire to the farmhouse to sup; which being over, large portions of ale and cider enable them to carouse and vociferate until one or two o'clock in the morning.

At the same house, or that of a neighbouring farmer, a similar scene is renewed, beginning between eight and nine o'clock in the morning following, and so continued through the precious season of the wheat harvest in this county. It must be observed that the labourers thus employed in reaping receive no wages; but in lieu thereof they have an invitation to the farmer's house to partake of a harvest frolic, and at Christmas, during the whole of which time, and which seldom continues less than three or four days, the house is kept open night and day to the guests, whose behaviour during the time may be assimilated to the frolics of a bear-garden.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

THE BULL-FIGHTS OF SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

The following particulars were communicated to the Gentleman's Magazine of this month by a witness to a recent bull-fight in the city of Lisbon. Speaking without reference to its humane character or moral tendency, the writer remarks that no spectacle in the world can be compared, for interest and effect, to a Spanish bull-fight, every part of which is distinguished for striking parade or alarming danger.

The grand sweep of the amphitheatre in Cadiz, Seville, or Madrid, crowded with a gay and variegated mass of eager and shouting spectators, and garnished at distances with boxes for the judges, the court, or the music—the immense area in which the combats take place, occupied with the picadors in silk jackets, on horses richly caparisoned, and with the light skipping and elastic bandarilleros, carrying their gaudy silk flags to provoke the rage and to elude the attack of the bull, form of themselves a fine sight before the combat begins. When the door of the den which encloses the bull is opened, and the noble animal bursts in wildly upon this, to him, novel scene—his eyes glaring with fury—when he makes a trot or a gallop round the ring, receiving from each horseman as he passes a prick from a lance, which enrages him still more—when, meditating vengeance, he rushes on his adversaries, and scatters both horsemen and bandarilleros, by his onset, ripping up and casting the horses on the ground, and causing the bandarilleros to leap over the railing among the spectators—or when, after a defeated effort or a successful attack, he stands majestically in the middle of the area, scraping up the sand with his hoof, foaming at the mouth, and quivering in every fibre with rage, agony, or indignation, looking towards his adversaries, and meditating a fatal rush—the sight combines every element of interest and agitation which can be found in contempt of danger, in surprising boldness, and great animal force intensely excited. The horns of the Spanish bull are always sharp, and never covered. An animal of sufficient power and spirit to command popular applause frequently kills five or six horses, the riders taking care to fall over on the side most distant from the enemy, and being instantly relieved from their perilous situation by the bandarilleros, who attract his attention: and the bull himself is always killed in the ring by the matador, who enters in on foot with his bright flag in the left hand, and his sword in the right, and who, standing before the enraged animal waiting the favourable moment when he bends his head to toss him on his horns, plunges his sword into his neck or spine in such a fatal manner that he frequently falls instantaneously as if struck by lightning. This last operation is as dangerous as it is dexterous. At the moment in which the matador hits the bull, the pointed horn must be within an inch or two of his heart, and if he were to fail he must himself be the victim. When he succeeds in levelling to the ground with a single stroke his furious and irresistible enemy, the music strikes up, the applauses of the amphitheatre are showered upon the conqueror, he stalks proudly round the area, strewed with dead horses, and reddened with blood, bowing first to the judges of the fight, and then to the spectators, and leaves the place amid enthusiastic vivas for his successful audacity. The field of slaughter is then cleared by a yoke of horses, richly decorated with plumes on their heads and ribands on their manes, to which the dead bull or horses are attached, and by which they are dragged out at a gallop. That no part of the amusement may want its appropriate parade, this operation goes on amid the sound of a trumpet, or the playing of a military band. The horsemen are then remounted anew, and enter on fresh steeds—the door of the den is again opened—another furious animal is let loose on the possessors of the ring, till ten or twelve are thus sacrificed.

The bull-fights in Lisbon are a very inferior species of amusement to this, though much better than I was led to anticipate. Here the bulls are generally not so strong or so spirited as the Spanish breed. In the morning of the sport, the tips of their horns, instead of being left sharp, are covered with cork and leather. None but one horseman appeared in the ring at a time—no havoc was of course made among the horses; bulls were introduced and baited without being killed, and the matador, though he sometimes displays the same dexterity, never encounters the same danger as in Spain. In Lisbon the most interesting part of the sport consists in an operation which could not be practised in Spain, and is conducted by performers who are unknown where bull-fighting is more sanguinary. These performers are what they call here homens de furcado, or men of the fork; so denominated from their bearing a fork with which they push or strike the head of the bull, when he throws down a man or a horse. After the bull, not destined to be killed, has afforded amusement enough, these men go up before him, one of them trying to get in between his horns, or to cling to his neck, till the rest surround, master him, and lead him out of the area. The man of the fork, who gets between the bull's horns, is sometimes tossed in the air or dashed to the ground, and in this one of the chief dangers of the fight consists. On Sunday one of them was dashed down so violently as to be carried out of the ring in a state of insensibility. Only four bulls were killed out of the twelve exhibited. The rest being reserved for future sport, were either dragged out of the ring in the manner above described, or, when supposed to be too strong to be mastered by the men of the fork, were tamely driven out among a flock of oxen introduced into the area as a decoy. Another peculiarity of the Lisbon bull-fights is the presence of a buffoon on horseback called the Neto, who first enters the ring to take the commands of the Inspector, and occasionally bears the shock of the bull, to the no small diversion of the lower class of spectators. The Spanish bull-fight is too serious an affair for a buffoon: it is a tragedy, and not a farce.

From these few points of comparison, it is evident that the Spanish exhibition is a much more splendid and interesting spectacle than that of Portugal, and that there is nearly as much difference as between a field of battle and the sham fight of a review. Probably the Portuguese sport has danger enough to excite common interest, and more than enough to be a popular diversion. The place where these entertainments are given at Lisbon, is a large octagon amphitheatre called the Saletre, near the public walk behind the Rocio. It has what is called a pit, into which the bull sometimes, but rarely, jumps, and on one side two tier of boxes, and is capable of containing about 4,000 or 5,000 spectators. The amusements are always exhibited on Sundays, and are generally attended with great crowds. On Sunday last every part of the amphitheatre was full, and the people betrayed such extravagant marks of pleasure as I could not have expected, from their usual sedate and dull habits.

THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

A TUCUMANESE SCHOOLMASTER

The following day, July the 5th, we pursued our journey, intending to breakfast at a village very pleasantly situated, called Vinará, six leagues from the river of Santiago, and remarkable for the appearance of industry which it presented. No one here seemed to live in idleness; the women, even while gazing at our carriage, were spinning away at the same time. I observed too, that here the cochineal plant spread a broader leaf, and flourished with greater luxuriance in the gardens and hedge-rows of the cottages around, than at any place I had before visited. "Industry is the first step to improvement, and education follows hard upon it," thought I, as on foot, attracted by a busy hum of voices, we made our way through an intervening copse towards the spot whence it seemed to come. A fig-tree, the superincumbent branches of which shaded a wide circuit of ground, arrested our progress; and looking through an opening among the large green leaves, we espied the village pedagogue, elevated on his authoritative seat, which was attached to the trunk of the tree. He was reading a lecture on the heads of his scholars—a phrenological dissertation, if one might judge from its effects, with a wand long enough to bump the caput of the most remote offender. I began to think myself in some European district, certainly not from the late samples I had seen of the country, in the heart of the Columbian continent. There, however, I was in reality, and in the fine province of Tucuman, with nearly half the globe's surface between Europe and myself. The picture was a very striking one occurring with these reflections. The beautiful vegetable-roofed school-room, too, struck my fancy. What a delightful natural study!—the cool broad leaves overarching it, and heightening the interest of the scene. The striplings were seated, without regular order, on the grass, under a rotunda of this magnificent foliage. Some were cross-legged, bawling Ba, Be, Bi; others, with their knees for a table, seemed engraving rather than writing, upon a wooden tablet, the size of a common slate. One or two, who appeared to be more advanced in their studies, were furnished with a copy-book, an expensive article in that place. Some were busy at arithmetic, while, every moment, whack went the rod upon the crown of the idler or yawner.