Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 264, July 14, 1827

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 10, No. 264, July 14, 1827

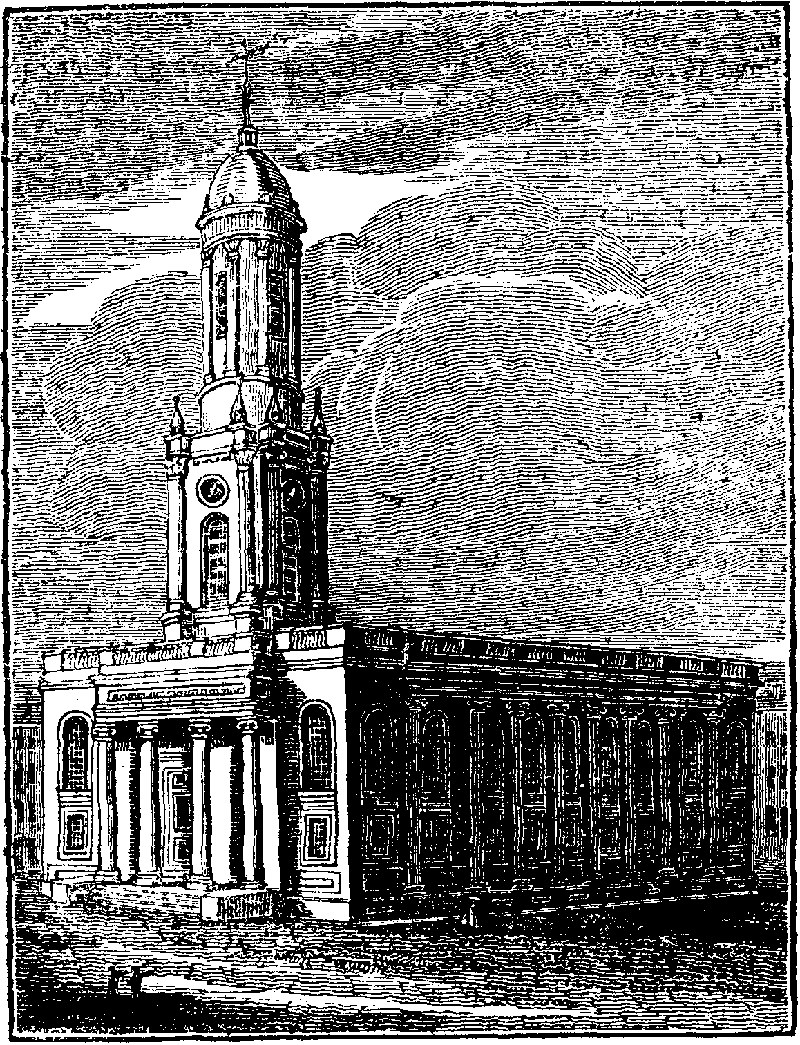

ARCHITECTURAL ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW CHURCH, REGENT'S PARK

The architectural splendour which has lately developed itself in and about the precincts of the parish of St. Mary-le-Bonne, exhibits a most surprising and curious contrast with the former state of this part of London; and more particularly when compared with accounts extracted from newspapers of an early date.

Mary-le-Bonne parish is estimated to contain more than ten thousand houses, and one hundred thousand inhabitants. In the plans of London, in 1707, it was a small village one mile distant from the Metropolis, separated by fields—the scenes of robbery and murder. The following from a newspaper of 1716:—"On Wednesday last, four gentlemen were robbed and stripped in the fields between Mary-le-Bonne and London." The "Weekly Medley," of 1718, says, "Round about the New Square which is building near Tyburn road, there are so many other edifices, that a whole magnificent city seems to be risen out of the ground in a way which makes one wonder how it should find a new set of inhabitants. It is said it is to be called by the name of Hanover Square! On the other side is to be built another square, called Oxford Square." From the same article I have also extracted the dates of many of the different erections, which may prove of benefit to your architectural readers, as tending to show the progressive improvement made in the private buildings of London, and showing also the style of building adopted at later periods. Indeed, I would wish that some of your correspondents—F.R.Y., or P.T.W., for instance, would favour us with a list of dates answering this purpose. Rathbone-place and John-street (from Captain Rathbone) began 1729. Oxford market opened 1732. Newman-street and Berners-street, named from the builders, between 1723 and 1775. Portland-place and street, 1770. Portman-square, 1764. Portman-place, 1770. Stratford-place, five years later, on the site of Conduit Mead, built by Robert Stratford, Esq. This had been the place whereon stood the banquetting house for the lord mayor and aldermen, when they visited the neighbouring nine conduits which then supplied the city with water. Cumberland-place, 1769. Manchester-square the year after.

Previous to entering upon an architectural description of the superb buildings recently erected in the vicinity of Regency Park, I shall confine myself at present to that object that first arrests the attention at the entrance, which is the church; it has been erected under the commissioners for building new churches. The architect is J. Soane, Esq. There is a pleasing originality in this gentleman's productions; the result of extensive research among the architectural beauties of the ancients, together with a peculiar happy mode of distributing his lights and shadows; producing in the greatest degree picturesque effect: these are peculiarities essentially his own, and forming in no part a copy of the works of any other architect in the present day. The church in question by no means detracts from his merit in these particulars. The principal front consists of a portico of four columns of the Ionic order, approached by a small flight of steps; on each side is a long window, divided into two heights by a stone transum (panelled). Under the lower window is a raised panel also; and in the flank of the building the plinth is furnished with openings; each of the windows is filled with ornamental iron-work, for the purpose of ventilating the vaults or catacombs. The flank of the church has a central projection, occupied by antae, and six insulated Ionic columns; the windows in the inter-columns are in the same style as those in front; the whole is surmounted by a balustrade. The tower is in two heights; the lower part has eight columns of the Corinthian order. Example taken from the temple of Vesta, at Tivoli; these columns, with their stylobatæ and entablature, project, and give a very extraordinary relief in the perspective view of the building. The upper part consists of a circular peristyle of six columns; the example apparently taken from the portico of the octagon tower of Andronicus Cyrrhestes, or tower of the winds, from the summit of which rises a conical dome, surmounted by the Vane. The more minute detail may be seen by the annexed drawing. The prevailing ornament is the Grecian fret.

Mr. Soane, during his long practice in the profession, has erected very few churches, and it appears that he is endeavouring to rectify failings that seem insurmountable in the present style of architecture,—that of preventing the tower from having the appearance of rising out of the roof, by designing his porticos without pediments; if this is the case, he certainly is indebted to a great share of praise, as a pediment will always conceal (particularly at a near view) the major part of a tower. But again, we find ourselves in another difficulty, and it makes the remedy as bad as the disease,—that of taking away the principal characteristic of a portico, (namely, the pediment), and destroying at once the august appearance which it gives to the building; we find in all the churches of Sir Christopher Wren the campanile to form a distinct projection from the ground upwards; thus assimilating nearer to the ancient form of building them entirely apart from the main body of the church. I should conceive, that if this idea was followed by introducing the beautiful detail of Grecian architecture, according to Wren's models it would raise our church architecture to a very superior pitch of excellence.

In my next I shall notice the interior, and also the elevation towards the altar.

C. DAVY.

Furnivals' Inn,

July 1, 1827.

THE MONTHS

THE SEASON

The heat is greatest in this month on account of its previous duration. The reason why it is less so in August is, that the days are then much shorter, and the influence of the sun has been gradually diminishing. The farmer is still occupied in getting the productions of the earth into his garners; but those who can avoid labour enjoy as much rest and shade as possible. There is a sense of heat and quiet all over nature. The birds are silent. The little brooks are dried up. The earth is chapped with parching. The shadows of the trees are particularly grateful, heavy, and still. The oaks, which are freshest because latest in leaf, form noble clumpy canopies; looking, as you lie under them, of a strong and emulous green against the blue sky. The traveller delights to cut across the country through the fields and the leafy lanes, where, nevertheless, the flints sparkle with heat. The cattle get into the shade or stand in the water. The active and air-cutting-swallows, now beginning to assemble for migration, seek their prey about the shady places; where the insects, though of differently compounded natures, "fleshless and bloodless," seem to get for coolness, as they do at other times for warmth. The sound of insects is also the only audible thing now, increasing rather than lessening the sense of quiet by its gentle contrast. The bee now and then sweeps across the ear with his gravest tone. The gnats

"Their murmuring small trumpets sounden wide:"—SPENSER.and here and there the little musician of the grass touches forth his tricksy note.

The poetry of earth is never dead;When all the birds are faint with the hot sun,And hide in cooling trees, a voice will runFrom hedge to hedge about the new-mown mead:That is the grasshopper's.1The strong rains, which sometimes come down in summer-time, are a noble interruption to the drought and indolence of hot weather. They seem as if they had been collecting a supply of moisture equal to the want of it, and come drenching the earth with a mighty draught of freshness. The rushing and tree-bowing winds that precede them, the dignity with which they rise in the west, the gathering darkness of their approach, the silence before their descent, the washing amplitude of their out-pouring, the suddenness with which they appear to leave off, taking up, as it were, their watery feet to sail onward, and then the sunny smile again of nature, accompanied by the "sparkling noise" of the birds, and those dripping diamonds the rain-drops;—there is a grandeur and a beauty in all this, which lend a glorious effect to each other; for though the sunshine appears more beautiful than grand, there is a power, not even to be looked upon, in the orb from which it flows; and though the storm is more grand than beautiful, there is always beauty where there is so much beneficence.—The Months.

BATHING

It is now the weather for bathing, a refreshment too little taken in this country, either summer or winter. We say in winter, because with very little care in placing it near a cistern, and having a leathern pipe for it, a bath may be easily filled once or twice a week with warm water; and it is a vulgar error that the warm bath relaxes. An excess, either warm or cold, will relax, and so will any other excess; but the sole effect of the warm bath moderately taken is, that it throws off the bad humours of the body by opening and clearing the pores. As to summer bathing, a father may soon teach his children to swim, and thus perhaps may be the means of saving their lives some day or other, as well as health. Ladies also, though they cannot bathe in the open air, as they do in some of the West Indian islands and other countries, by means of natural basins among the rocks, might oftener make a substitute for it at home in tepid baths. The most beautiful aspects under which Venus has been painted or sculptured have been connected with bathing; and indeed there is perhaps no one thing that so equally contributes to the three graces of health, beauty, and good temper; to health, in putting the body into its best state; to beauty, in clearing and tinting the skin; and to good temper, in rescuing the spirits from the irritability occasioned by those formidable personages, "the nerves," which nothing else allays in so quick and entire a manner. See a lovely passage on the subject of bathing in Sir Philip Sydney's "Arcadia," where "Philoclea, blushing, and withal smiling, makeing shamefastnesse pleasant, and pleasure shamefast, tenderly moved her feet, unwonted to feel the naked ground, until the touch of the cold water made a pretty kind of shrugging come over her body; like the twinkling of the fairest among the fixed stars."—Ibid.

INSECTS

Insects now take the place of the feathered tribe, and, being for the most part hatched in the spring, they are now in full vigour. It is a very amusing sight in some of our rural rambles, in a bright evening after a drizzling summer shower, to see the air filled throughout all its space with sportive organized creatures, the leaf, the branch, the bark of the tree, every mossy bank, the bare earth, the pool, the ditch, all teeming with animal life; and the mind that is ever framed for contemplation, must awaken now in viewing such a profusion and variety of existence. One of those poor little beings, the fragile gnat, becomes our object of attention, whether we regard its form or peculiar designation in the insect world; we must admire the first, and innocently, perhaps, conjecture the latter. We know that Infinite Wisdom, which formed, declared it "to be very good;" that it has its destination and settled course of action, admitting of no deviation or substitution: beyond this, perhaps, we can rarely proceed, or, if we sometimes advance a few steps more, we are then lost in the mystery with which the incomprehensible Architect has thought proper to surround it. So little is human nature permitted to see, (nor perhaps is it capable of comprehending much more than permitted,) that it is blind beyond thought as to secondary causes; and admiration, that pure fountain of intellectual pleasure, is almost the only power permitted to us. We see a wonderfully fabricated creature, decorated with a vest of glorious art and splendour, occupying almost its whole life in seeking for the most fitting station for its own necessities, exerting wiles and stratagems, and constructing a peculiar material to preserve its offspring against natural or occasional injury, with a forethought equivalent to reason—in a moment, perhaps, with all its splendour and instinct, it becomes the prey of some wandering bird! and human wisdom and conjecture are humbled to the dust. We can "see but in part," and the wisest of us is only, perhaps, something less ignorant than another. This sense of a perfection so infinitely above us, is the natural intimation of a Supreme Being; and as science improves, and inquiry is augmented, our imperfections and ignorance will become more manifest, and all our aspirations after knowledge only increase in us the conviction of knowing nothing. Every deep investigator of nature can hardly be possessed of any other than a humble mind.

THE PEACOCK

(For the Mirror.)Of this bird, there are several species, distinguished by their different colours. The male of the common kind is, perhaps, the most gaudy of all the bird-kind; the length and beauty of whose tail, and the various forms in which the creature carries it, are sufficiently known and admired among us. India is, however, his native country; and there he enjoys himself with a sprightliness and gaiety unknown to him in Europe. The translators of Hindoo poetry concur in their description of his manners; and is frequently alluded to by the Hindoo poets.

"Dark with her varying clouds, and peacocks gay."It is affirmed, among the delightful phenomena which are observable at the commencement of the rainy season, (immediately following that of the withering hot winds,) the joy displayed by the peacocks is one of the most pleasing. These birds assemble in groups upon some retired spot of verdant grass; jump about in the most animated manner, and make the air re-echo with their cheerful notes.

"Or can the peacock's animated hail."The wild peacock is also exceedingly abundant in many parts of Hindoostan, and is especially found in marshy places. The habits of this bird are in a great measure aquatic; and the setting in of the rains is the season in which they pair; the peacock is, therefore, always introduced in the description of cloudy or rainy weather. Thus, in a little poem, descriptive of the rainy season, &c., the author says, addressing his mistress,—

"Oh, thou, whose teeth enamelled vie With smiling Cunda's pearly ray,Hear how the peacock's amorous cry Salutes the dark and cloudy day."And again, where he is describing the same season:—

"When smiling forests, whence the tuneful criesOf clustering pea-fowls shrill and frequent rise,Teach tender feelings to each human breast,And please alike the happy or distressed."The peacock flies to the highest station he can reach, to enjoy himself; and rises to the topmost boughs of trees, though the female makes her nest on the ground.

F.R.Y.

A WARNING TO FRUIT EATERS

(For the Mirror.)The mischiefs arising from the bad custom of many people swallowing the stones of plums and other fruit are very great. In the Philosophical Transactions, No. 282, there is an account of a woman who suffered violent pains in her bowels for thirty years, returning once in a month, or less, owing to a plum-stone which had lodged; which, after various operations, was extracted. There is likewise an account of a man, who dying of an incurable colic, which had tormented him many years, and baffled the effects of medicine, was opened after his death, and in his bowels was found the cause of his distemper, which was a ball, composed of tough and hard matter, resembling a stone, being six inches in circumference, when measured, and weighing an ounce and a half; in the centre of this there was found the stone of a common plum. These instances sufficiently prove the folly of that common opinion, that the stones of fruits are wholesome. Cherry-stones, swallowed in great quantities, have occasioned the death of many people; and there have been instances even of the seeds of strawberries, and kernels of nuts, collected into a lump in the bowels, and causing violent disorders, which could never be cured till they were carried off.

P.T.W.

THE NIGHTINGALE,

BY THE AUTHOR OF "AHAB."(For the Mirror.)In the low dingle sings the nightingale. And echo answers; all beside is still.The breeze is gone to fill some distant sail, And on the sand to sleep has sunk the rill.The blackbird and the thrush have sought the vale. And the lark soars no more above the hill,For the broad sun is up all hotly pale, And in my reins I feel his parching thrill.Hark! how each note, so beautifully clear, So soft, so sweetly mellow, rings around.Then faintly dies away upon the ear, That fondly vibrates to the fading sound.Poor bird, thou sing'st, the thorn within thy heart, And I from sorrows, that will not depart.S.P.J.SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

A NIGHT ATTACK

Charlton and I were in the act of smoking our cigars, the men having laid themselves down about the blaze, when word was passed from sentry to sentry, and intelligence communicated to us, that all was not right towards the river. We started instantly to our feet. The fire was hastily smothered up, and the men snatching their arms, stood in line, ready to act as circumstances might require. So dense, however, was the darkness, and so dazzling the effect of the glare from the bivouac, that it was not possible, standing where we stood, to form any reasonable guess, as to the cause of this alarm. That an alarm had been excited, was indeed perceptible enough. Instead of the deep silence which five minutes ago had prevailed in the bivouac, a strange hubbub of shouts, and questions, and as many cries, rose up the night air; nor did many minutes elapse, ere first one musket, then three or four, then a whole platoon, were discharged. The reader will easily believe that the latter circumstance startled us prodigiously, ignorant as we were of the cause which produced it; but it required no very painful exertion of patience to set us right on this head; flash, flash, flash, came from the river; the roar of cannon followed, and the light of her own broadside displayed to us an enemy's vessel at anchor near the opposite bank, and pouring a perfect shower of grape and round shot into the camp.

For one instant, and only for an instant, a scene of alarm and consternation overcame us; and we almost instinctively addressed to each other the question, "What can all this mean?" But the meaning was too palpable not to be understood at once. "The thing cannot end here," said we—"a night attack is commencing;" and we made no delay in preparing to meet it. Whilst Charlton remained with the picquet, in readiness to act as the events might demand, I came forward to the sentries, for the purpose of cautioning them against paying attention to what might pass in their rear, and keeping them steadily engaged in watching their front. The men were fully alive to the peril of their situation. They strained with their hearing and eyesight to the utmost limits; but neither sound nor sight of an advancing column could be perceived. At last, however, an alarm was given. One of the rifles challenged—it was the sentinel on the high road; the sentinel who communicated with him challenged also; and the cry was taken up from man to man, till our own most remote sentry caught it. I flew to his station; and sure enough the tramp of many feet was most distinctly audible. Having taken the precaution to carry an orderly forward with me, I caused him to hurry back to Charlton with intelligence of what was coming, and my earnest recommendation that he would lose no time in occupying the ditch. I had hardly done so, when the noise of a column deploying was distinctly heard. The tramp of horses, too, came mingled with the tread of men; in a word, it was quite evident that a large force, both of infantry and cavalry, was before us.

There was a pause at this period of several moments, as if the enemy's line, having effected its formation, had halted till some other arrangement should be completed; but it was quickly broke. On they came, as far as we could judge from the sound, in steady array, till at length their line could be indistinctly seen rising through the gloom. The sentinels with one consent gave their fire. They gave it regularly and effectively, beginning with the rifles on their left, and going off towards the 85th on their right, and then, in obedience to their orders, fell back. But they retired not unmolested. This straggling discharge on our part seemed to be the signal to the Americans to begin the battle, and they poured in such a volley, as must have proved, had any determinate object been opposed to it, absolutely murderous. But our scattered videttes almost wholly escaped it; whilst over the main body of the picquet, sheltered as it was by the ditch, and considerably removed from its line, it passed entirely harmless.

Having fired this volley, the enemy loaded again, and advanced. We saw them coming, and having waited till we judged that they were within excellent range, we opened our fire. It was returned in tenfold force, and now went on, for a full half hour, as heavy and close a discharge of musketry as troops have perhaps ever faced. Confident in their numbers, and led on, as it would appear, by brave officers, the Americans dashed forward till scarcely ten yards divided us; but our position was an admirable one, our men were steady and cool, and they penetrated no farther. On the contrary, we drove them back, more than once, with a loss which their own inordinate multitude tended only to render the more severe.

The action might have continued in this state about two hours, when, to our horror and dismay, the approaching fire upon our right flank and rear gave testimony that the picquet of the 85th, which had been in communication with us, was forced. Unwilling to abandon our ground, which we had hitherto held with such success, we clung for awhile to the idea that the reverse in that quarter might be only temporary, and that the arrival of fresh troops might yet enable us to continue the battle in a position so eminently favourable to us. But we were speedily taught that our hopes were without foundation. The American war-cry was behind us. We rose from our lairs, and endeavoured, as we best could, to retire upon the right, but the effort was fruitless. There too the enemy had established themselves, and we were surrounded. "Let us cut our way through," cried we to the men. The brave fellows answered only with a shout; and collecting into a small compact line, prepared to use their bayonets. In a moment we had penetrated the centre of an American division; but the numbers opposed to us were overwhelming; our close order was lost; and the contest became that of man to man. I have no language adequate to describe what followed. For myself, I did what I could, cutting and thrusting at the multitudes about me, till at last I found myself fairly hemmed in by a crowd, and my sword-arm mastered. One American had grasped me round the waist, another, seizing me by the wrist, attempted to disarm me, whilst a third was prevented from plunging his bayonet into my body, only from the fear of stabbing one or other of his countrymen. I struggled hard, but they fairly bore me to the ground. The reader will well believe, that at this juncture I expected nothing else than instant death; but at the moment when I fell, a blow upon the head with the butt-end of a musket dashed out the brains of the man who kept his hold upon my sword-arm, and it was freed. I saw a bayonet pointed to my breast, and I intuitively made a thrust at the man who wielded it. The thrust took effect, and he dropped dead beside me. Delivered now from two of my enemies, I recovered my feet, and found that the hand which dealt the blow to which my preservation was owing, was that of Charlton. There were about ten men about him. The enemy in our front were broken, and we dashed through. But we were again hemmed in, and again it was fought hand to hand, with that degree of determination, which the assurance that life and death were on the issue, could alone produce. There cannot be a doubt that we should have fallen to a man, had not the arrival of fresh troops at this critical juncture turned the tide of affairs. As it was, little more than a third part of our picquet survived, the remainder being either killed or taken; and both Charlton and myself, though not dangerously, were wounded. Charlton had received a heavy blow upon the shoulder, which almost disabled him; whilst my neck bled freely from a thrust, which the intervention of a stout leathern stock alone hindered from being fatal. But the reinforcement gave us all, in spite of wounds and weariness, fresh courage, and we renewed the battle with alacrity.