Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Journal of Negro History, Volume 7, 1922

With the cooperation of these friends and through travel the Director has been making a study of Slavery from the Point of View of the Slave. This has been done through questionnaires filled out by ex-slaves and former masters, through the collection of documents, and the study of local records. This study, however, is just beginning and will require much more time for completion. The Director expects to finish at an earlier date his studies of the Free Negro and the Development of the Negro in the Occupations.

The most significant achievement of the Association has been the success of the Director in increasing the income of the Association to about $12,000 a year. This substantial uplift has come in part from a large number of Negroes, who now more than ever appreciate the value of their records and the importance of popularizing the study thereof. A large number of Negroes have made small contributions and as many as forty have given the Association $25 each this year. Through the strong endorsement of Dr. J. F. Jameson and other noted historical scholars the Director secured from the Carnegie Corporation the much needed appropriation of $5,000 a year for each of the next five years. With this income the Association has paid all of its debts except that of the bonus of $1,200 a year promised the Director for 1919-1920 and 1920-1921. Besides, the Association has been enabled to employ a Business Manager and to pay the Director a regular salary that as soon as practicable he may sever his connection with all work and devote all of his time to the prosecution of the study of Negro Life and History.

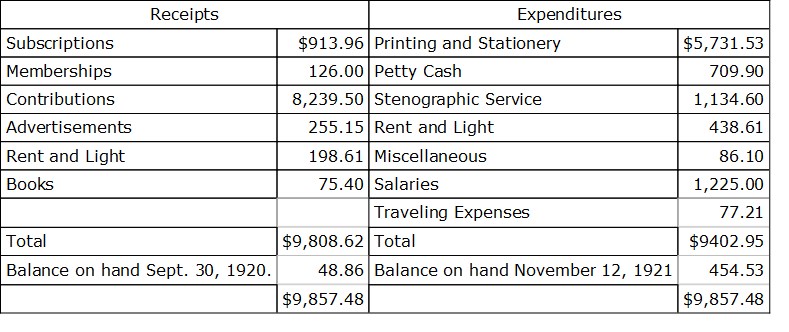

The details as to how the funds thus raised have been expended appear in the following report of the Secretary-Treasurer:

November 12, 1921.The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Washington, D. CGentlemen: I hereby submit to you a statement of the amount of money received and expended by the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Incorporated, from September 30, 1920, to November 12, 1921.

Upon the recommendation of the committee on nominations the officers of the Association were, in keeping with the custom of this body, elected by a motion to the effect that the Acting Secretary be instructed to cast the unanimous ballot of the Association, for those recommended by the committee on nominations, that is, for John R. Hawkins as President, for S. W. Rutherford as Secretary-Treasurer, for C. G. Woodson as Director and Editor, and as members of the Executive Council the three foregoing officers together with Julius Rosenwald, George Foster Peabody, James H. Dillard, Bishop R. A. Carter, R. R. Church, Albert Bushnell Hart, John W. Davis, Bishop John R. Hurst, A. L. Jackson, Moorfield Storey, Bishop R. E. Jones, Channing H. Tobias, Clement Richardson, and R. C. Woods.

The evening session of the 14th was held at the Eighth Street Baptist Church where were assembled a considerable representation of the members of the Association and a large number of persons seeking to learn of the work and to profit by the discussion of the Association. Dr. R. C. Woods, President of the Virginia Theological Seminary and College, presided. The first speaker of the evening, Dr. W. H. Stokes of Richmond, Virginia, delivered a well-prepared and instructive address on the value of tradition. His aim was to encourage the Negro race and other persons interested in its uplift to do more for the preservation and study of its records. The next speaker of the evening was Professor J. R. Hawkins, Financial Secretary of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He delivered a very forceful and informing discourse on the history of the Negro Church. How the church has figured in the life of the Negro; how it has been effective in promoting the progress of the race; and what it is doing to-day to present the case of the Negro to the world and offer him opportunities in other fields were all emphasized throughout this address. Dr. R. T. Kerlin, former Professor at the Virginia Military Institute, was then introduced. He briefly spoke about the importance of acquainting the white race with the achievements of the Negro, and showed that his task was not, therefore, to appeal to the Negroes, themselves, but to the white people, who too often misunderstand them.

The morning session of the 15th at the Virginia Theological Seminary and College was called to order by the newly elected President, Prof. John R. Hawkins. The Director, Dr. C. G. Woodson, was then introduced. He showed how the Negro is a menace to the position of the white man in trying to maintain racial superiority. The significant achievements of the Negro in Africa and this country were passed in rapid review to show how untenable this position of the white man is and how unlikely it can continue in view of the fact that the Negro is accomplishing more now than ever before in the history of the race. Professor John R. Hawkins then delivered a brief address showing how the development of the schools and the maintenance of the proper school spirit through teachers and students can be made effective in the social uplift of the race. President Trigg of Bennet College then followed with impressive remarks expressing his interest in the cause and his confidence in those who are now doing so much to preserve the records of the Negro and to popularize the study of them throughout this country and abroad.

There was no afternoon session of the Association except a brief meeting of the Executive Council, to which the public was not invited. The conference closed with the evening session at the Eighth Street Baptist Church, where a large audience was addressed by Dr. I. E. McDougle, of Sweet Briar College, Dr. E. Crooks, of Randolph-Macon College, and Professor Bernard Tyrrell of the Virginia Theological Seminary and College. Dr. McDougle briefly discussed Negro history as a neglected field, showing that it is generally unexplored, and introducing an abundance of material which may be discovered with little effort. He spoke, moreover, of Negro History as a neglected subject, giving statistical information as to the places where the subject is now being taught and the manner in which such instruction is offered. Dr. Crooks spoke for a few minutes on self-respect as a means by which the race may develop power. He unfortunately, however, drifted into a discussion of certain phases of the race problem and disgusted his audience by advancing ideas with which, as he was informed, Negroes cannot agree. Professor Tyrrell then delivered a scholarly address on Negro ancestry and brought forward from his study of ancient history and especially that of Africa, facts showing that the Negro race has made a record of which it may well feel proud. He explained, moreover, how historians since the early days have become prejudiced against the proper treatment of the achievements of Africans and have endeavored to convince the world that the record of the race is not significant.

This meeting on the whole was a success, above and beyond that of any other hitherto held. The attendance was large, the enthusiasm ran higher, and the financial support secured far exceeded that of other meetings. There was expressed a general interest in the plans for the future prosecution of the work and the intention to give it more support that it may be extended in all of its ramifications throughout this country and even abroad.

The Journal of Negro History

Vol. VII—April, 1922—No. 2

NEGRO CONGRESSMEN A GENERATION AFTER

The period of reconstruction which followed the Civil War presented to the statesmen of that time three problems of unusual significance. These were: what should be the status of the eleven Confederate States; what should be done with the leaders of the Confederacy; and finally, what should be the rôle to be played by the several millions of freedmen? In the effort to deal effectively with these problems the Thirty-ninth and Fortieth Congresses adopted a reconstruction policy which provided for the readmission of the formerly rebellious States to the Union, the imposition of political disabilities upon many former Confederates, and the bestowal of citizenship and suffrage upon the freedmen. Upon the enlarged electorate the reconstruction of the States was undertaken.

That the freedmen, comprising in many communities a preponderance of voting power, should elect to public office ambitious outstanding men of their race was expected. At that time, therefore, Negroes attained not only local and State offices of importance, but also sat in the United States Congress. Indeed, during the period from 1871 to 1901, the latter year marking the passing of this type of Congressman, twenty-two Negroes, two of whom were senators, held membership in Congress. It seems, moreover, that men like Menard of Florida, Pinchback of Louisiana, Lee and others, though unable to prove their contentions, were, nevertheless, contestants with good title.

This situation, no less unique than it was interesting, has become the source of interminable debate. It has been contended that because of the ignorance of the blacks, in letters, in manners, in business, and in the affairs of State, it was a serious mistake to enfranchise them, thus making possible for a period however brief their virtual direction of the political affairs of some of the Southern States. Consistent in principle, historians of this conviction have viewed with abhorrence the seating of black men in the highest legislative assembly of the land. Not all men, however, have concurred in this opinion. There were those who had precisely the opposite view, basing their argument on the necessity of the plan of reconstruction effected, in order to preserve to the Union the fruits of its victory.

The merits of that reconstruction are not here, however, at issue. Of far greater import for our consideration is the single fact that Negroes were thereby sent to Congress. Did the Negroes elected to Congress justify by their achievements their presence there? To what extent did they give direction to the thought and policies which were to govern and control in this nation? Manifestly an impartial judgment in this matter may be most adequately arrived at by the setting up of certain criteria of excellence expected to inhere in Congressmen and measuring by these the achievements of these functionaries. Considering the matter in this light, therefore, the following questions are advanced as bearing a direct relationship to the services of these Congressmen. First, what of their mental equipment to perform the tasks of law makers? Second, as measured by their experience in public positions of trust and by their grasp of the public questions at that time current, to what extent did they show capacity for public service? Third, in what directions were their chief interests manifested?

Evidences of Mental Equipment

Regarding the Negro Congressmen in the light of the standards already referred to, we shall first make inquiry as to their mental fitness to function as law makers. Broadly considered, they may be divided into two groups: first, those who possessed but limited education; second, those who were college bred.

Among the men comprising the first group, certain common characteristics are noticeable: first, they were mainly members of the earliest Reconstruction Congresses, beginning with the Forty-first, in which Negroes held membership, and were therefore but little removed from slavery; second, some of them were born of slave parents or had been, themselves, slaves; third, others were brought up in communities which expressly prohibited the establishment of educational institutions for Negroes; and fourth, all of them, by dint of severe application in later years, secured, prior to their election to Congress, a better education than rudimentary instruction. The members of this group were twelve in number, including Long107 of Georgia; De Large,108 Rainey,109 Ransier,110 and Smalls111 of South Carolina; Lynch112 and Bruce113 of Mississippi; Haralson114 and Turner115 of Alabama; Hyman116 of North Carolina; Nash117 of Louisiana; and Walls118 of Florida.

As many as ten of the twenty-two Negro congressmen were men of college education. This training, however, varied widely in scope and purpose. Two men of this group became ministers of the gospel. One of them, Richard H. Cain119 of South Carolina, was trained at Wilberforce University, Xenia, Ohio, whence he left in 1861, at the age of thirty-six years, to begin a career in his chosen field; the other, Hiram E. Revels120 of Mississippi, was educated at the Quaker Seminary in Union County, Indiana. Prior to their election to Congress, both of these men attracted wide attention as churchmen. Cain was for four years the pastor of a church in Brooklyn, N. Y., after which his congregation sent him as a missionary to the freedmen of South Carolina. Senator Revels, on the other hand, was widely known as a lecturer in the States of Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, and Missouri. For some time he preached in Baltimore, taught school in St. Louis, and among other things, organized churches and lectured in Mississippi. The wide experiences of both gentlemen offered to them unusual opportunities to develop the power, keenness of insight, and knowledge of human nature so essential to the leadership of men.

To some of these future Congressmen, the profession of teaching seemed more attractive than the ministry. Three of the number were destined to become educators. One of them, Henry P. Cheatham121 of North Carolina, attended the public and private schools near the town of Henderson, and was later graduated with honor from the college department of Shaw University. Immediately thereafter, in 1882, he was elected to the principalship of the Plymouth State Normal School, where he served until 1895. The second member of this group, George W. Murray122 of South Carolina, won by competitive examination a scholarship at the reconstructed University of South Carolina. There he remained until 1876, his junior year, when by the accession to power of an administration unfriendly to the coeducation of the races, he was forced to withdraw. For many years thereafter, Murray was engaged as a teacher in the schools of his native county.

John Mercer Langston123 of Virginia, the third member of the group of educators, was graduated, in 1849, at the age of twenty, from Oberlin College. Four years later, in 1853, he completed the work of the theological department of that school. Because of his ripe scholarship, moreover, unusual honors were conferred upon him by several American colleges and universities, and he was the recipient of several honorary memberships in scientific and literary institutions and associations of foreign countries. Indeed, there have sat in Congress few men of greater mental power and energy than John Mercer Langston.

Of the twenty-two Negroes who have sat in Congress, five were members of the legal profession. One of these men represented Alabama, two South Carolina, and two North Carolina. Robert Brown Elliott, the first member of this group of legally trained leaders, was perhaps the most outstanding and certainly the most brilliant of the Negroes who have served in Congress. Elliott124 entered the High Hollow Academy of London, England, in 1853, at the age of eleven years. In 1859, he was graduated from Eton College. Later, he studied law and was admitted to the bar, where he practiced for some time before the courts of South Carolina. This superior training of Elliott no doubt contributed in large measure to his eminence in debate, which was so often manifested during the memorable sessions of the 42nd and 43rd Congresses.

James T. Rapier125 of Alabama, one of the really brilliant men in this group, acquired a liberal education, after which he studied law and practiced in his native State. Another member of the legal group was James E. O'Hara126 of Enfield, North Carolina. Following his academic training which was received in New York City, O'Hara studied law, first, in North Carolina, and later at Howard University in Washington. In June, 1871, he was admitted to the bar of his State.

Two others of this group were Miller and White. The first one, Thomas E. Miller,127 of Beaufort, South Carolina, attended the free public school for Negroes in his native city. In 1872 he was graduated from the Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. Later, Miller read law, and in 1875 was admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of his State. The second of these two, George Henry White128 of North Carolina, studied first in his native State and later at Howard University. While there he pursued concurrently courses in liberal arts and in law. In January, 1879, he was admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of his State.

Their Public Service Prior to Membership in Congress

Perhaps the most accurate method whereby one's capacity for the performance of any service may be measured is that which seeks, first, to establish the experience of the individual in the performance of the identical or similar services, and second, to evaluate the degree of skill with which the individual, at a given time, performs the particular service. Regarded in this light, therefore, we subject the Negro Congressmen to this test: As measured by their experience in public positions of trust and confidence and by their grasp of the great public questions at that time current, to what extent did they show capacity for public service?

The first part of our query lends itself to solution without difficulty. Indeed, one may with great ease establish the fact that, with but few exceptions, these men, prior to their election to Congress, had held public offices of honor and trust. A case in point is that of John Mercer Langston129 of Virginia. While never a member of a State legislature, Langston was, nevertheless, brought often into other public service. Indeed he early attracted attention in Ohio by his service as a member of the Council of Oberlin and by his record in other township offices. Langston served as dean of the Law Department of Howard University, and in 1872 became Vice-President and Acting President of that institution. In 1885 he became President of the Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute. He served, moreover, as Inspector-General of the Bureau of Freedmen, a member of the Board of Health of the District of Columbia, Minister resident and Consul-General to Haiti, and Charge d'Affaires to Santo Domingo. His election to Congress, therefore, was the crowning achievement of a lifelong public career.

Hyman,130 O'Hara,131 Cheatham,132 and White,133 all of North Carolina, had held public office prior to their election to Congress. Hyman and White had each been members of the State Senate, the former for six years, from 1868 to 1874, while O'Hara and White had each served in the lower house of the legislature. Hyman had been a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1868, moreover, while O'Hara, who had also served as chairman of the Board of Commissioners of the County of Halifax, had been a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1875. For the eight years from 1886 to 1894, White served as prosecuting attorney for the second judicial district of the State, while Cheatham, the fourth member of the North Carolina delegation, had held but one office, that of Register of Deeds for Vance County.

It is especially significant that each one of the Negro Reconstruction Congressmen from South Carolina, namely Cain,134 De Large,135 Elliott,136 Rainey,137 Ransier,138 and Smalls139 were members of the State Constitutional Convention of 1868. Two of them, Cain and Rainey, had been formerly State Senators; Smalls had served two terms in the Senate and four in the House; while each of the others had been members for one term or more in the lower branch of the legislature. Ransier, moreover, had held, prior to his election to Congress, the high office of lieutenant-governor of the State; Elliott had served as adjutant-general, and Smalls had held successively the offices of lieutenant-colonel, brigadier-general and major-general in the State militia.

Of the two South Carolinians who served in Congress after the Reconstruction, Thomas E. Miller140 was for four terms a member of the lower chamber of the State legislature and for one term a member of the Senate. Furthermore, he was for one term a school commissioner of his county, and received also his party's nomination for the office of lieutenant-governor of the State. Indeed, of the entire South Carolina group, Murray, alone, seems to have been elected to Congress without previously having held public office.141 Jefferson F. Long,142 of Georgia, was not unlike Mr. Murray in that the former had never held public office. In this, his experience differed from that of Walls, of Florida, who had been a member of the Florida State Senate.

Alabama sent to Congress three Negroes, Turner,143 Rapier,144 and Haralson.145 Of these men Haralson alone had had experience in the legislature prior to his election to Congress, having served in both branches of that body. Turner was elected in 1868 to the city council of Selma. Later he became tax collector of Dallas County, but because of his inability to secure honest men as assistants, resigned the office. The third member of this group, James T. Rapier, served as an assessor and later as a collector of internal revenue in his State.

The two Negro United States Senators, Hiram R. Revels146 and B. K. Bruce,147 both of Mississippi, and Representative John R. Lynch148 of the same State, had all served in public office before they were sent to Congress. Senator Revels had held several local offices in Vicksburg, while Senator Bruce, before he came to the Senate, had been sheriff, a member of the Mississippi levee board, and for three years the tax collector of Bolivar County. John R. Lynch, on the other hand, had served not only as justice of the peace, but also two terms in the lower house of the legislature, during the latter one of which he was the Speaker of that body. Unlike the Congressmen from Mississippi, Nash149 of Louisiana held office for the first time when his state elected him a representative to Congress.

Accessible records and impartial and unbiased historians support the contention that with a few exceptions the record of these Negro functionaries was honorable. Corrupt government was not always the work of the Negro. In the chapter on reconstruction in his The Negro in Our History, C. G. Woodson states that local, state, and federal administrative offices, which offered the most frequent opportunity for corruption, were seldom held by Negroes, but rather by the local white men and by those from the North who had come South to seek their fortunes. In many respects selfish and sometimes lacking in principle, these men became corrupt in several States, administering the government for their own personal ends. "Most Negroes who have served in the South," says he, "came out of office with honorable records. Such service these Negroes rendered in spite of the fact that this was not the rule in that day." New York, according to the same authority, was dominated by the Tweed ring, and the same white men who complained of Negro domination robbed the governments of the Southern States of thousands of dollars after the rule of the master class was reestablished.

Negro Congressmen in Action

With the facts concerning the earlier experiences of these Congressmen in public life a matter of record, attention may now be centered upon the second aspect of the question of their capacity for public service—namely, that of their reactions to the great public questions of their day. Perhaps this topic may be most properly treated first by determining what were the problems of greatest public moment during the period in which these men were in Congress. From the year 1871—the period of service of the first Negro in Congress—throughout the first year of the administration of Rutherford B. Hayes, there were brought prominently before the public mind the questions of reconstruction, economic, social, and political, in the North and West as well as in the South. The exploitation of the public domain in the West, the development of transcontinental railroads and other means of communication, the plea for sound money, the economic regeneration of the South, the proper adjustment of the social relations between the two races living in that section, and the readjustment of political control in the former Confederate States were the great issues upon which, during this period, the attention of the nation was focused.