Полная версия

Полная версияThe Continental Monthly, Vol. 6, No. 6, December 1864

It is noticeable, however, as a proof of the high esteem in which the people hold the science, that the shops of the chemists and apothecaries are kept by a superior class of people, more intelligent in appearance than their neighbors, and holding a higher rank.

Of the lower trades there are innumerable shops, the variety of which is almost bewildering. Every art and manufacture has its minute subdivisions, and one meets, at every step, signs of the superior civilization of the people in their admirable division of labor. Silk looms are working in the open streets, shoemakers and tailors are each plying their art in their narrow shops. In one they manufacture little paper offerings for the gods, in another the gods themselves, in the next their worshippers are supplied with joss-sticks or gayly colored candles of tallow, mounted on slim sticks, that they may be stuck in the sand before the divinity. Here you will find a printer hard at work taking impressions on their delicate paper; next a bookbinder, who sews the leaves with withes of paper, while in the next shop you can procure the almanac for the year, months before it is required. In August, 1863, they were selling copies of the almanac for 1864. Probably this work has the largest circulation of any in the world, hanging, as it does, in every house. The only exception may be the Bible, which, it is to be hoped, will yet be as widely circulated in China as it is among the other nations of the world.

Numbers of the people are engaged in the delicate carving we so much admire in the ivory toys scattered throughout Europe and America, and a vast number of people in preparing the hanging screens with curious devices, quaint pictures, and sentences from Confucius, which are found in almost every house of the better class. They have a great fondness for the proverbs and wise sayings which, are thus kept always before their children, like the very good rules and aphorisms we see on the walls of our Sunday schools.

A good example of the minute subdivision of the Chinese trades is seen in the shops devoted exclusively to the sale of camel's-hair pencils, and others for that of the little squares of red paper, covered with hieroglyphics, which we receive on a pack of fire-crackers, and which constitute its 'chop.'

Jewellers' shops contain very little interesting to a foreigner—most of the rings and brooches are trashy articles of jade-stone, a greenish stone which resembles agate or cornelian in opaqueness. The armlets are of silver, and of the same substance are the large thin circles worn by the women of Foh-Kien in the ear and resting on the shoulder. Pins for the fantastic pyramid they erect with their rich black hair are rather pretty, but are generally ornamented with false pearls. For pearls the Chinese have a passion, but it requires a judge of the article to purchase any from them, nine tenths of those in the shops being fictitious. Seed pearls are also used by them as medicines. In the back streets it is not uncommon to find places where they make them, and others where artists are engaged in cutting and polishing on the lathe the few precious stones they possess. Rock crystal is one of their favorites, and from it they cut beautiful vases and goblets that are sometimes as clear as glass. In this, however, they are surpassed by the Japanese, whoso crystal globes cannot be distinguished from the most perfect glass. They also cut vases and carve odd figures in an arsenical stone, of reddish color, with a grain like granite, which is little known in other countries.

In Shanghai the shops for the sale of china and porcelain-ware do not present as fine an assortment as those of Canton, where vases costing fabulous sums are to be seen, but they are rich with the peculiar pottery of Soo-Chow. Just at present the display of this ware is not as fine as usual, owing to the occupation of that city by the Tae-Pings, but enough remains on hand to show its beauty and general usefulness. Chinese porcelain ware is as well known in every civilized country of the world as in China itself, and has ceased to be a curiosity unless when intelligently viewed in its historical character, for all these quaint scenes scattered over the magnificent vases we receive illustrate some event in Chinese history, or some custom which obtains among the people.

When evening approaches and the shops are lit up with lanterns, the numerous and brilliant lantern warehouses attract the attention: some of the goods they display (and at nightfall they light every lantern in the shop) are extremely beautiful and costly; all kinds are to be obtained, from the fine hall-lamp of painted glass to the sixpenny lantern to be carried in the hand. At night these gay lights give much animation to the busy streets. Having gone across Shanghai from the south gate to the French Concession one dark night, after the city gates were closed, a good opportunity of seeing the interior of a Chinese city after nightfall (which few foreigners care to avail themselves of) presented itself. The people were slowly closing their shops for the night. Here and there a shopkeeper was counting his cash, and calculating at his counter with the help of the abacus; many of them were sitting at the doors of their houses, smoking in the evening air; the barbers were still at work preparing their customers for the night. Like Washington Irving, these may have considered a good clean shave the best soporific. Here and there a citizen of the better class was to be seen picking his way by the light of a lantern, held by a boy, and twice we met sedan chairs containing women, preceded by a lantern bearer. The passage of two sedans in these narrow streets is a difficult and unpleasant process, the bearers generally managing to grind your shins against a wall. At night it is still more difficult to avoid contact, and the coolies are incessantly shouting, in a sing-song voice, to prepare the way. As it was, in the narrower streets we passed between files of dusky figures and black, inquisitive eyes, ranged on either side to barely allow passage. The cook-shops were deserted, and the attendants busy in putting out the fires; only the places where lanterns or candles were sold seemed to be doing an active trade, although it had scarcely struck nine. At ten o'clock no doubt all were asleep, for hosts of beggars and poor wretches were snoring by the roadsides. The most picturesque groups passed in this evening stroll were those on the bridges, where, by the light of tallow candles, men and boys were gambling and fighting crickets. Although probably there was not another European or American within the walls of the city, the passage was as safe as if made at noonday, guarded by a file of soldiers.

A visit to Shanghai would be incomplete if the traveller failed to inspect the numerous and very curious temples, and to contrast them with the church edifices erected in the heart of the city by the Protestant missionaries. There is one without the walls, in the French Concession, where all the instruments of torture, the devilish devices of heathen cruelty, are to be seen, a horrid spectacle. The largest of the temples, however, is within the walls, approached through a wide court, with a fountain (not in use) in the centre. This court is crowded with fortune tellers, conjurors, and gamblers of every kind. Some of these gentry play a game very much like thimble-rigging, in which copper cash, appears under different inverted teacups. Every man who approaches the idol draws from among the fortune tellers a stick or a piece of paper, from the figure on which he is supposed to tell whether his prayer will succeed, or the work he contemplates prove lucky. Entering the shrine, it is difficult to see for a few moments, so gloomy is the place and so grimy every object with the smoke of joss offerings from time immemorial. A kind of altar faces the worshippers, with a box of sand, in which are stuck the burning joss-sticks. Before this is a cushion, on which they prostrate themselves, telling their beads, as they recite their prayers inaudibly, and bowing to the earth at intervals of a few minutes. Behind the altar are the idols. These hideous figures are twice the size of life, and of frightful shape and features, the principal god being in a tent-like shrine, which permits only a glimpse of his grim features in the background. On his right hand is the figure of a man with the beak of an eagle, and on his left a very grotesque divinity, with a third eye, like that of the Cyclops, in the centre of his forehead. These two figures, again, are supported by gigantic guardians, one on either side, who have nothing absolutely monstrous about them, being distinguished by their saturnine expression. That to the right hand bears a striking likeness to Daniel Webster's stern and well-known features. The deep-set eye and compressed lip were those of the great expounder.

A heavy cloud from the burning candles and paper offerings filled the air, and the smell of candle snuff mingled with that of incense. A high railing separated the worshippers from the idols, but the priests were quite indifferent and not at all exclusive; so, passing around and without removing our hats, we made a close inspection of the respected carvings. A nearer view did not increase their attractions, so, passing up a flight of stairs, we entered a room where the bonzes were busy praying for rain and apparently going through a species of litany with open books in their hands. Our entrance stopped proceedings for a minute or two, but they soon resumed, quite indifferently, singing and drawling as though it were tedious, tiresome work.

They were all good-looking men, in the prime of life, dressed in scarlet and embroidered robes of much richness. Unlike the rest of the people, they neither shaved nor wore the cue. We found them drawn in a line before the altar, from which they were separated by a screen: an open porch at their back let in light and air. Each priest had before him a little table with a fancy gilt screen upon it, and as they slowly proceeded with their drawl, at convenient intervals, each made a slight bow behind his screen, his head touching it. As they did this with the regularity of drilled soldiers, and to the pounding of a tom-tom, they evidently were chanting in chorus, although the ear would have failed to distinguish it. The tom-toms and wooden drums were beaten at the pleasure of the parties in charge: nothing like time was apparent to any but a Chinese ear.

The idol was a little gilt figure, about six inches high, with the body of a beast and the head of a man. His peculiarity was the possession of a supplementary eye, which, as his natural pair squinted horribly, no doubt was very useful. His position was on a little table surrounded by tall candles; whether they were borrowed from the Roman Catholics or the Catholics borrowed the custom from them is a question for the student of church history. Before the idol was placed another table with ten elegant bowls, scarcely larger than our teacups, filled with the choicest fruits and grains that the market afforded. Each article was perfect of its kind. Rice, tea, the nelumbium, and agaric, a species of fungus, were among them. Just then the country being in great want of rain, the priests were trying the coaxing process, and tempting the god with the best chow-chow to be had; but the next day they got out of patience, and were to be met parading him through the dusty streets, exposed to a fierce sun, for the purpose of giving him to understand that the heat was quite as disagreeable as they had represented it.

Their arguments for this proceeding are extremely logical: they say that Joss, in his cool temple, laughs at them, and is disposed to think that they are humbugging him; therefore, if they give him two or three hours of good skin-roasting in the sun, he will be much more likely to come to terms, to avoid a repetition of the process. As they do this every day until rain comes, it is of course seen in a short time, if they are patient, that it never fails in the end.

Indeed, it is quite common to meet in all the large cities processions of priests, followed by the rabble, who are giving 'Joss an airing.' The eminently practical object of these mummeries argues very little genuine respect for the deity, an inference that has often been drawn by missionaries from other points in their treatment of their idols.

Their worship of them, such as it is, is almost universal. Every house has its shrine and altar, and even in the porches of foreign residents in the quarters occupied by the Chinese servants, one sometimes (although not often) sees a little figure in a niche, with a tiny joss-stick before it. Every junk and sampan has its tutelary idol. A little shrine of bamboo of the size of a common birdcage is built for it, sometimes fixed and sometimes movable. The interior of this was gilded once, but the gilt is worn and tarnished by smoke and water. It has doors that open when the joss-sticks are to be burnt before the toy figure that presides on a miniature throne. A sampan whose owners are too poor to supply themselves with decent clothing, will be sure to have its tawdry baby-house and doll idol, and it frequently has in addition a roll of paper, four feet by one, like a window curtain, with, a gay picture of Joss, in a scarlet dress, in the act of dancing, and generally in a very absurd posture for such a respectable character.

Every evening at sunset there is a prodigious hubbub from the junks on the Woosung, made with tom-toms, drums, and other unmelodious instruments, which are vigorously beaten for ten or fifteen minutes, to bring good luck, and propitiate the devils, or frighten them away for the night. From the shore, the rapid motions of a dozen arms on the high poop of each junk, tossed aloft in the dusk, and the discordant, harsh sounds that come from so many vessels at once, arrest the attention of the stranger, and once seen and heard, are never forgotten.

The pagodas, so often mentioned in accounts of the Chinese empire, appear to be more numerous in the mountainous districts, where they add greatly to the picturesque charm of the scenery, and are believed to be connected with the religious ceremonies of the people. In the flat country around Shanghai they are not to be met with; at least it was not our fortune to see any during our brief stay. The only structure like a tower, if we except the turrets on the city walls and watch towers erected within the past few years, when the Tae-Pings have threatened the city, is a tall, white monument, rising to the height of twenty feet, and without inscription or distinguishing mark of any kind. It looks like a fine, white tomb, higher and more ambitious than usual, and truly it is a 'whited sepulchre'! Baby Tower, it is called by the foreign residents, for it is filled with the bones of infants—not such as have died a natural death, as Bayard Taylor asserts, but which have been thrust into this horrid monument of heathen cruelty when but a few hours old. Humanity shudders at the thought! These dazzling white baby towers, with their mockery of purity, their object known to all men, and openly inviting, as it were, the most unnatural and heartless of murders, are among the most hideous spectacles to be met with in a heathen land. True, a river or a pond will be pointed out to you in other parts of China, or in India, where babies are daily drowned like puppies or kittens; but they do not affect the mind with such a horror as these palpable structures, erected with the best skill of their architects for this express purpose. The water closes over the murdered infant, and no trace of the crime remains; but here is a tower—a high tower—with deep foundations, filled with the bones of murdered babes that have been accumulating for generations.

No wonder that Christian mothers, resident in the East, cannot speak of them or see them without a shudder, and never willingly pass them in their drives. Who knows but they might hear, if they approached the tower, the wail of some poor infant just thrown in, or meet its father returning from his cruel errand!

At Shanghai the Baby Tower stands on the southwest side of the city, without the walls, but at Foo-Chow, where the crime of infanticide is still more prevalent, they use no baby towers, but have provided ponds for this express purpose. It is the saddest part of this great national crime of the Chinese, that it is sanctioned by the mandarins, and viewed as a disagreeable necessity, not as a crime.

It has been the fashion of late years to deny the existence of this abomination; the doubters, wise in their own conceit, insisting that the crime is too great for human nature.

Human nature, unfortunately, has proved but a frail barrier to crime of this character in all parts of the world, and the facts of Chinese infanticide are indisputable. The witnesses are too numerous, the crime is too public, and the evidences of it too notorious to deny its existence. The children destroyed are girls; the most common methods of destroying them are: 1st, by drowning in a tub of water; 2d, by throwing into some running stream; 3d, by burying alive. The last-named mode is adopted under the hope and with the superstitious belief that the next birth will be a boy. The excuse is that it is too expensive to educate a girl, but if some friend will take the child to bring up as a wife for a little boy, the parents will sell or give away the infant rather than destroy it. The regular price is two thousand copper cash, or $2, for every year of their lives; for sometimes a girl will be saved for a year or two, and then sold for a wife or slave. Many instances have come to the notice of missionaries where large families of girls have been destroyed. There is one woman now employed as a nurse in a missionary's family at Fuh-Chow, who says that her mother had eight girls and three boys, and that she was the only girl permitted by her father to live. We never heard of an instance of a boy's being destroyed at birth. There is a village about fifteen miles from Fuh-Chow, which is swarming with boys, but where girls are very scarce. The people account for it themselves by alleging the common practice of killing the girls at birth, a practice which is indulged in by the rich as well as by the poor.2

But to enter into all the particularities of Chinese life which attract the attention at Shanghai as in other cities, would be to compile an account of China and her customs.

The points of real importance to be considered in connection with Shanghai, which is fast becoming the commercial centre of Chinese exports, are the extent to which foreigners have an influence on the people in modifying their habits, increasing their knowledge, and dispelling their prejudices. The growth of European influence and the complete opening of the Chinese empire, in which immense advances have been made in the last three years, will, in time, it is to be hoped, lead to the diffusion of the Christian religion, a work attended with such gigantic difficulties, at the present day, that one cannot sufficiently admire the courage, patience, and faith which actuate missionaries to this empire. No representations of these difficulties which reach the Christian world have done justice to them, for it is necessary to observe the heartlessness, self-conceit, and prodigious prejudices of the Chinese to appreciate the noble zeal of the missionaries. The course of trade and much more correct notions of the power and objects of the Western nations, and the firmness with which they use the former to secure the latter, are unquestionably breaking up with rudeness the ridiculous ideas of the Chinese concerning their own importance and superior wisdom. If once they can be made learners in good earnest, the battle is half won, for none doubt their intelligence. European influence, alone, has effected great changes in five years, and European and Chinese combined may, in the five years to come, work out still greater reforms.

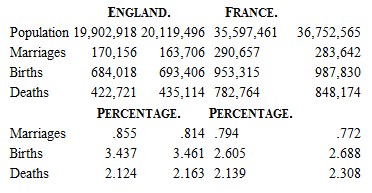

COMPARATIVE VIEW OF MOVEMENT OF POPULATION OF

ON HEARING A 'TRIO

'All thoughts, all passions, all delights,Whatever stirs this mortal frame,'Thrilled through the wildering harmoniesThat from the music came.All soothing sounds of nature blent,In wonderful accord,With pleadings, wild and passionate,From human hearts outpoured.The wailings of the world's sad heart,Oppressed with social wrongs,In mournful monotones were mixedWith sounds of angel songs.The falling of a nation's tearsO'er Freedom's prostrate form,Dew droppings sweet from starry spheres,Swift-rushing wings of storm.The voices of Time's children three—Past, Present, Future, blentIn that wild 'trio's' harmony,Thrilled each fine instrument.And, at the sound, my soul awoke,And saw the dawning clearOf Freedom's coming day illumeEarth's clouded atmosphere!THE IDEAL MAN FOR UNIVERSAL IMITATION; OR, THE SINLESS PERFECTION OF JESUS

(A POSITIVE REPLY TO STRAUSS AND RENAN.)

The first impression which we receive from the life of Jesus, is that of perfect innocency and sinlessness in the midst of a sinful world. He, and He alone, carried the spotless purity of childhood untarnished through his youth and manhood. Hence the lamb and the dove are his appropriate symbols.

He was, indeed, tempted as we are, but he never yielded to temptation. His sinlessness was at first only the relative sinlessness of Adam before the fall, which implies the necessity of trial and temptation, and the peccability, or the possibility of the fall. Had he been endowed with absolute impeccability from the start, he could not be a true man, nor our model for imitation; his holiness, instead of being his own self-acquired act and inherent merit, would be an accidental or outward gift, and his temptation an unreal show. As a true man, Christ must have been a free and responsible moral agent; freedom implies the power of choice between good and evil, and the power of disobedience as well as obedience, to the law of God. But here is the great fundamental difference between the first and the second Adam: the first Adam lost his innocence by the abuse of his freedom, and fell by his own act of disobedience into the dire necessity of sin; while the second Adam was innocent in the midst of sinners, and maintained his innocence against all and every temptation. Christ's relative sinlessness became more and more absolute sinlessness by his own moral act, or the right use of his freedom in the perfect active and passive obedience to God. In other words, Christ's original possibility of not sinning, which includes the opposite possibility of sinning, but excludes the actuality of sin, was unfolded into the impossibility of sinning, which can not sin because it will not. This is the highest stage of freedom, where it becomes identical with moral necessity, or absolute and unchangeable self-determination for goodness and holiness. This is the freedom of God and of the saints in heaven, with this difference: that the saints attain that position by deliverance and salvation from sin and death, while Christ acquired it by his own merit.

In vain we look through the entire biography of Jesus for a single stain or the slightest shadow on his moral character. There never lived a more harmless being on earth. He injured nobody, he took advantage of nobody, he never spoke an improper word, he never committed a wrong action. He exhibited a uniform elevation above the objects, opinions, pleasures, and passions of this world, and disregard to riches, displays, fame, and favor of men. 'No vice that has a name can be thought of in connection with Jesus Christ. Ingenious malignity looks in vain for the faintest trace of self-seeking in His motives; sensuality shrinks abashed from His celestial purity; falsehood can leave no stain on Him who is incarnate truth; injustice is forgotten beside His errorless equity; the very possibility of avarice is swallowed up in His benignity and love; the very idea of ambition is lost in His divine wisdom and divine self-abnegation.'

The apparent outbreak of passion in the expulsion of the profane traffickers from the temple is the only instance on the record of his history which might be quoted against his freedom from the faults of humanity. But the very effect which it produced, shows that, far from being the outburst of passion, the expulsion was a judicial act of a religious reformer, vindicating in just and holy zeal the honor of the Lord of the temple. It was an exhibition, not of weakness, but of dignity and majesty, which at once silenced the offenders, though superior in number and physical strength, and made them submit to their well-deserved punishment without a murmur, and in awe of the presence of a superhuman power. The cursing of the unfruitful fig tree can still less be urged, as it evidently was a significant symbolical act, foreshadowing the fearful doom of the impenitent Jews in the destruction of Jerusalem.