Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Continental Monthly, Vol. 4, No. 1, July, 1863

Let us now examine the relations of New England to these proposed works. Vermont, upon Lake Champlain, by the enlarged system, connecting her with the Hudson, the St. Lawrence, and the lakes, would be greatly advanced in wealth and population. But with cheapened transportation to and from Lake Champlain or the Hudson, not only Vermont, but all New England, in receiving her coal and iron, and her supplies from the West, and in sending them her manufactures, will enjoy great advantages, and the business of her railroads be vastly increased. So, also, New England, on the Sound, and, in fact, the whole seaboard and all its cities. Bridgeport, New Haven, New London, Providence, Fall River, New Bedford, Boston, Portland, Bangor, Belfast, and Eastport will all transact an immense increased business with New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and the West. As the greatest American consumer of Western breadstuffs and provisions, and of our iron and coal, and the principal seat of domestic manufactures, the augmented reciprocal trade of New England with the South and West will be enormous. Her shipping and shipbuilding interests, her cotton, woollen, worsted, and textile fabrics, her machinery, engines, and agricultural implements, boots and shoes, hats and caps, her cabinet furniture, musical instruments, paper, clothing, fisheries, soap, candles, and chandlery, in which she has excelled since the days of Franklin, and, in fact, all her industrial pursuits, will be greatly benefited. The products of New England in 1860, exclusive of agriculture and the earnings of commerce, were of the value of $494,075,498. But, in a few years after the completion of these works, this amount will be doubled. Such is the skilled and educated industry of New England, and such the inventive genius of her people, that there is no limit to her products, except markets and consumers. As New York increases, the swelling tide of the great city will flow over to a vast extent into the adjacent shores of Connecticut and New Jersey, and Hoboken, West Hoboken, Weehawken, Hudson City, Jersey City, and Newark will meet in one vast metropolis. Philadelphia will also flow over in the same way into Camden and adjacent portions of New Jersey, whose farms already greatly exceed in value those of any other State. The farms of New Jersey in 1860 were of the average value of $60.38 per acre, while those of South Carolina, the great leader of the rebellion, with all her boasted cotton, rice, and tobacco, and her 402,406 slaves, were then of the average value of $8.61 per acre. (Census Table 36.) And yet there are those in New Jersey who would drag her into the rebel confederacy, cover her with the dismal pall of slavery, and who cry Peace! peace! when there is no peace, except in crushing this wicked rebellion. The States of the Pacific, as the enlarged canals reached the Mississippi and Missouri, and ultimately the base of the Rocky mountains, would be greatly advanced in all their interests. Agricultural products and other bulky and heavy articles that could not bear transportation all the way by the great Pacific railroad, could be carried by such enlarged canals to the Mississippi and Missouri, and ultimately to the base of the Rocky mountains, and thence, by railroad, a comparatively short distance to the Pacific, and westward to China and Japan. In order to make New York and San Francisco great depots of interoceanic commerce for America, Europe, Asia, and the world, these enlarged canals, navigated by large steamers, and ultimately toll free, are indispensable.

We have named, then, all the Territories, and all the thirty-five States, except three, as deriving great and special advantages from this system. These three are Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida, with a white population, in 1860, of 843,338. These States, however, would not only participate in the increased prosperity of the whole country, and in augmented markets for their cotton, rice, sugar, tobacco, and timber, and in cheaper supplies of Eastern manufactures, coal, iron, and Western products, but they would derive, also, special advantages. They have a large trade with New Orleans, which they would reach more cheaply by deepening the mouth of the Mississippi. They could pass up Albemarle sound, by the interior route, to Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, or the West, and take back return cargoes by the same route. Georgia, also, by her location on the Tennessee river, together with South Carolina, connected with that river at Chattanooga, would derive great benefits from this connection with the enlarged canals and improved navigation of the West, sending their own and receiving Western products more cheaply.

Thus, every State and every Territory in the Union would be advanced in all their interests by these great weeks, and lands, farms, factories, town and city property, all be improved in value.

But there is another topic, connected with this subject, of vast importance, particularly at this juncture, to which I must now refer. It is our public lands, the homestead bill, and immigration. On reference to an article on this subject, published by me in the November number of The Continental Monthly, it will be found that our unsold public lands embraced 1,649,861 square miles, being 1,055,911,288 acres, extending to fifteen States and all the Territories, and exceeding half the area of the whole Union. The area of New York, being 47,000 square miles, is less than a thirty-fifth of this public domain. England (proper), 50,922 square miles; France, 203,736; Prussia, 107,921; and Germany, 80,620 square miles. Our public domain, then, is more than eight times as large as France, more than fifteen times as large as Prussia, more than twenty times as large as Germany, more than thirty-two times as large as England, and larger (excluding Russia) than all Europe, containing more than 200,000,000 of people. As England proper contained, in 1861, 18,949,916 inhabitants, if our public domain were as densely settled, its population would exceed 606,000,000, and it would be 260,497,561, if numbering as many to the square mile as Massachusetts. These lands embrace every variety of soil, products, and climate, from that of St. Petersburg to the tropics.

After commenting on the provisions of our homestead bill, which gives to every settler, American or European, 160 acres of this land for ten dollars (the cost of survey, etc.), I then said:

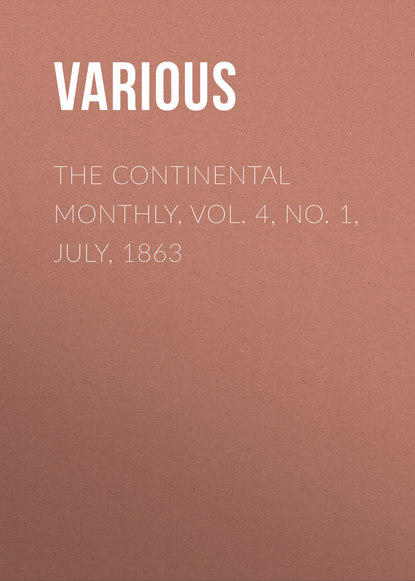

'The homestead privilege will largely increase immigration. Now, besides the money brought here by immigrants, the Census proves that the average annual value of the labor of Massachusetts per capita was, in 1860, $220 for each man, woman, and child, independent of the gains of commerce—very large, but not given. Assuming that of the immigrants at an average annual value of only $100 each, or less than thirty-three cents a day, it would make, in ten years, at the rate of 100,000 each year, the following aggregate:

'In this table the labor of all immigrants each year is properly added to those arriving the succeeding year, so as to make the aggregate the last year 1,000,000. This would make the value of the labor of this million of immigrants in ten years, $550,000,000, independent of the annual accumulation of capital, and the labor of the children of the immigrants (born here) after the first ten years, which, with their descendants, would go on constantly increasing.

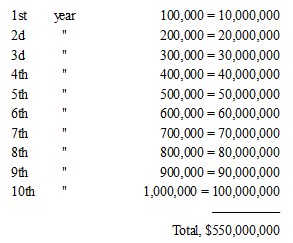

'But, by the official returns (p. 14, Census), the number of alien immigrants to the United States, from December, 1850, to December, 1860, was 2,598,216, or an annual average of 260,000.

'The effect, then, of this immigration, on the basis of the last table, upon the increase of national wealth, was as follows:

'Thus, the value of the labor of the immigrants, from 1850 to 1860, was $1,430,000,000, making no allowance for the accumulation of capital, by annual reinvestment, nor for the natural increase of this population, amounting, by the Census, in ten years, to about twenty-four per cent. This addition to our wealth, by the labor of the children, in the first ten years, would be small; but in the second and each succeeding decade, when we count children, and their descendants, it would be large and constantly augmenting. But the Census shows that our wealth increases each ten years at the rate of 126.45 per cent. (Census Table 35.) Now, then, take our increase of wealth, in consequence of immigration, as before stated, and compound it at the rate of 126.45 per cent. every ten years, and the result is largely over $3,000,000,000 in 1870, and over $7,000,000,000 in 1880, independent of the effect of any immigration succeeding 1860. If these results are astonishing, we must remember that immigration here is augmented population, and that it is population and labor that create wealth. Capital, indeed, is but the accumulation of labor. Immigration, then, from 1850 to 1860, added to our national products a sum more than double our whole debt on the 1st of July last, and augmenting in a ratio much more rapid than its increase, and thus enabling us to bear the war expenses.'

As the homestead privilege must largely increase immigration, and add especially to the cultivation of our soil, it will contribute vastly to increase our population, wealth, and power, and augment our revenues from duties and taxes.

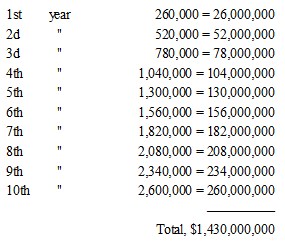

As this domain is extended over fifteen States and all the Territories, the completion of these enlarged canals, embracing so large a portion of them, would be most advantageous to all, and the inducement to immigration would greatly increase, and immigration must soon flow in from Europe in an augmented volume. Indeed, when these facts are generally known in Europe, the desire of small renters, and of the working classes, to own a farm, and cultivate their own lands here, must bring thousands to our shores, even during the war. But it will be mainly when the rebellion shall have been crushed, the power of the Government vindicated, its authority fully reëstablished, and slavery extinguished, so as to make labor honorable everywhere throughout our country, and freedom universal, that this immigration will surge upon our shores. When we shall have maintained the Union unbroken against foreign and domestic enemies, and proved that a republic is as powerful in war as it is benign in peace, and especially that the people will rush to the ranks to crush even the most gigantic rebellion, and that they will not only bear arms, but taxes, for such a purpose, the prophets of evil, who have so often proclaimed our Government an organised anarchy, will lose their power to delude the people of Europe. And when that people learn the truth, and the vast privileges offered them by the Homestead Bill, there will be an exodus from Europe to our country, unprecedented since the discovery of America. The wounds inflicted by the war will then soon be healed, and European immigrants, cultivating here their own farms, and truly loyal to this free and paternal Government, from which they will have received this precious gift of a farm for each, will take the place of the rebels, who shall have fled the country. We have seen that the total cost of our railroads and canals, up to this date, was $1,335,285,569, and I have estimated the probable cost of these enlarged works as not exceeding one tenth of this sum, or $133,528,556. Let us now examine that question. We have seen that our 4,650 miles of canals cost $132,000,000, being $28,387 per mile, or less, by $8,395 per mile, than our railroads. It will be recollected that a large number of miles of these canals have already the requisite depth of seven feet, and width of seventy, and need only an enlargement of their locks. It appears, however, by the returns, that the Erie canal, the Grand Junction, Champlain canal, and the Black River, Chemung, Chenango, and Oswego, in all 528 miles, are all seven feet deep, and seventy feet wide, and cost $83,494 per mile, while the average cost of all our canals, varying from forty to seventy-five feet in width, and from four to ten in depth, was $28,387 per mile. Assuming $28,000 per mile as the average cost of the canals requiring enlargement, and $83,000 that of those per mile having already the requisite dimensions, the difference would be $55,000 per mile, as the average cost of those needing increased dimensions.

The estimated cost, then, would stand as follows:

The conjectural estimate heretofore made by me was $133,528,556, or one tenth the cost of our existing railroads and canals, and exceeding, by $1,528,556, the cost of all our present 4,650 miles of canal. Deduct this from the above $133,528,556, leaves $34,268,556, to be applied to improving the St. Clair flats, the Mississippi river, deepening its mouth, and for the ship canal round the Falls of Niagara.

No estimate is now presented of the cost of the canal from Lake Champlain to the St. Lawrence, because that requires the coöperation of Canada.

The railroads of our country would increase their business, with our augmented wealth and population, especially in the transportation of passengers and merchandise. They would also obtain iron cheaper for rails, boilers, and engines, timber for cars, breadstuffs and provisions for supplies, and coal or wood for their locomotives.

Great, however, as would be the effect of these works in augmenting our commerce, wealth, and population, their results in consolidating and perpetuating our Union would be still more important. When the Ohio, Mississippi, and Missouri, and all their tributaries, arterializing the great valley, shall be united by the proposed routes with the lakes, the St. Lawrence, the Hudson, Delaware, Susquehanna, Chesapeake, and Albemarle, what sacrilegious hand could be raised against such a Union? We should have no more rebellions. We should hear no more of North, South, East, and West, for all would be linked together by a unity of commerce and interests. Our Union would become a social, moral, geographical, political, and commercial necessity, and no State would risk by secession the benefit of participating in its commerce. We should be a homogeneous people, and slavery would disappear before the march of civilization, and of free schools, free labor, free soil, free lakes, rivers, and canals. It is the absence of such a system (aided by slavery), drawing the West and Southwest, by a supposed superior attraction, to the Gulf, that has led the Southwest into this rebellion. But with slavery extinguished, with freedom strengthening labor's hand, with education elevating the soul and enlightening the understanding, and with such communications uniting all our great lakes and rivers, East and West, all crowned with nourishing towns and mighty cities, with cultured fields and smiling harvests, exchanging their own products and fabrics, and those of the world, by flying cars and rushing steamers, revolt or disunion would be impossible. Strike down every barrier that separates the business of the North and East from that of the South and West, and you render dissolution impossible. In commerce, we would be a unit, drawing to us, by the irresistible attraction of interest, intercourse, and trade, the whole valley of the lakes and St. Lawrence. Whom God had united by geography, by race, by language, commerce, and interest, political institutions could not long keep asunder. Of all foreign nations, those which would derive the greatest advantages from such an union would be England and France, the two governments which a wicked pro-slavery rebellion invites to attempt our destruction. With such a commerce, and with slavery extinguished, we would have the Union, not as it was, but as our fathers intended it should be, when they founded this great and free republic. We should soon attain the highest civilization, and enjoy the greatest happiness of which our race is capable. So long as slavery existed here, and we were divided into States cherishing, and States abhorring the institution, so long as free and forced labor were thus antagonized, we could scarcely be said to have a real Union, or to exist truly as a nation. Slavery loomed up like a black mountain, dividing us. Slavery kept us always on the verge of civil war, with hostility to liberty, education, and progress, and menacing for half a century the life of the republic. The question then was not, Will any measure, or any construction of the constitution, benefit the nation? but, Will it weaken or strengthen slavery? All that was good, or great, or national, was opposed by slavery—science, literature, the improvement of rivers and harbors, homesteads for the West, defences and navies for the East. American ocean steamers were sacrificed to foreign subsidies, and all aid was refused to canals or railroads, including that to the Pacific, although essential to the national unity. Slavery was attempted to be forced on Kansas, first by violence and invasion, and then by fraud, and the forgery of a constitution. Defeated in Kansas by the voice of the people, slavery then took the question from the people, and promulgated its last platform in 1860, by which all the Territories, nearly equal in area to the States, were to be subjected forever as Territories to slavery, although opposed by the overwhelming voice of their people. Slavery was nationalized, and freedom limited and circumscribed with the evident intent soon to strangle it in all the States, and spread forced labor over the continent, from the North to Cape Horn. Failing in the election, slavery then assailed the vital principle of the republic, the rule of the majority, and inaugurated the rebellion. Slavery kept perjured traitors for months in the cabinet and the two Houses of Congress, to aid in the overthrow of the Government. Then was formed a constitution avowedly based on slavery, setting it up as an idol to be worshipped, and upon whose barbaric altars is now being poured out the sacrificial blood of freemen. But it will fail, for the curse of God and man is upon it. And when the rebellion is crushed, and slavery extinguished, we shall emerge from this contest strengthened, purified, exalted. We shall march to the step and music of a redeemed humanity, and a regenerated Union. We shall feel a new inspiration, and breathe an air in which slavery and every form of oppression must perish.

Standing upon these friendly shores, in a land which abolished slavery in the twelfth century, and surrounded by a people devoted to our welfare, looking westward, along the path of empire, across the Atlantic, to my own beloved country, these are my views of her glorious destiny, when the twin hydras of slavery and rebellion are crushed forever.

If our Irish adopted citizens could only hear, as I now do, the condemnation of slavery and of this revolt, by the Irish people; if they could hear them, as I do, quote the electric words of their renowned Curran against slavery, and in favor of universal emancipation; if they could listen, as they repeated the still bolder and scathing denunciations of their great orator, O'Connell, as he trampled on the dehumanizing system of chattel slavery, they would scorn the advice of the traitor leaders, who, under the false guise of Democracy, but in hostility to all its principles, would now lure them, by the syren cry of peace, into the destruction of the Union, which guards their rights, and protects their interests.

The convention now assembled at Chicago, can do much to inaugurate a new era of civilization, freedom, and progress, by aiding in giving to the nation these great interior routes of commerce and intercourse, in the centre of which your great city will hold the urn, as the long-divorced waters of the lakes and the Mississippi are again commingled, and the Union linked together by the imperishable bonds of commerce, interest, and affection.

WOMAN

The ever-present phenomenon of revolution bears two forms. They may be discrete or concrete, but they are two—ideas, movement,—cause, result—force, effect. And progressive humanity marches upon its future with ideas for its centre, movement its right and left wings. Not a step is taken till the Great Field-Marshal has sent his orders along the lines.

Revolutions go by periods. Are they possibly controlled or influenced in these years by the stellar affinities of the north pole? Is that capricious functionary leading up to Casseopeia, in this cycle, or Andromeda, that we find ourselves turning from great Hercules, fiery Bootes, and even neglecting the shining majesty of belted, sworded Orion, to consider woman? I have not consulted the astronomers. The stars of the heavens are in their places. Male and female, the groups come to us in winter and retire in summer: their faint splendors fall down upon our harvest nights, and then give way to the more august retinue of the wintry solstice. The boreal pivot, whose journal is the awful, compact blue, may, for aught I know, be hobnobbing at this moment with the most masculine of starry masculinities. But if it be, it is in little sympathy with the magnetic pole of human thought, whose fine point turns unwaveringly in these days of many revolutions to woman as the centre and leader of the grandest of them all.

A great storm overtook an ancient navigator of the Ægean. He called on his gods, he importuned them, but the waves rolled and raged the more angrily the more he prayed. 'Neptune, wilt thou not save me?' 'Go below,' was the uncourteous answer, and, as with a great blow struck by the hand of the busy deity, the vessel was suddenly suspended midway between the surface and the depths of the waters. What a peaceful spot she had reached! The astonished mariner looked around him in wonder more than gratitude. 'Good deity,' said he, taking breath, 'I prayed not to be saved thus from the storm, but in it. Return me to the upper world, I beseech thee, and let me do my stroke in its battle.'

Storms have swept over the ages as winds over the blue Ægean, and woman, shrinking from their blasts and the agitations that have followed them, has prayed to her gods, and been suspended between the depths of man's depravity and the heights of his achievements, around whose wintry peaks winds of ambition have roared, storms of vaulting self-love have gathered, tempests of passion have contended in angry and fierce strife. To brighten the heights they assailed each one, to clear the lofty airs embracing them. They shine now where clouds were wont to hover; sunshine steeps the rugged declivities where mists of ages hung their impenetrable folds, paths invite where unknown, forbidding fastnesses repelled even daring feet, and thus the stormy career of conflict is vindicated in its results. The dove testifies a certain divinity in the Doing which has produced it.

But that still region where the more timid life has nestled undaring, unadventured, shrinking from the struggle and the strife above, recoiling from the seething foulness below—what have we in this dreamland inhabited by woman? And wherefore the earnest turning thitherward, in our day, of so many brave, so many earnest, so many sad, so many yearning, aspiring eyes? Wherefore the restlessness, wherefore the groans of imprisonment here, wherefore the passionate longings, the resolute, deep, inextinguishable purpose of escape? Make way, O propitious gods; I can no longer be saved from this struggle of life, but through it. This mariner must be brought to the surface, or the waters will be parted before her by the conquering power in her own soul, and she will present herself there unaided. But not in the fierce spirit of a combatant, not as a conqueror—only as one moved by divine purpose to reach and take her place, to touch and accomplish her work.

What are the qualities of this new soldier in the field of human struggle? Whence comes and whither goes she?

These inquiries point us to the ideas of the Woman Revolution—its Movements will be deductions from them.

Man knows neither woman nor her whence or whither. He acknowledges her a Mystery from his earliest acquaintance with her to the present day. Whatever his conquests over the hidden and the mysterious elsewhere in nature, here is a mystery that confronts him whenever he turns hither—nay, that grows by his attempts at mastering it. The permanently mysterious is only that which exceeds us, and we study this but to learn how widely its embracing horizon can spread as we advance. Thus the woman of the nineteenth century is an incomparably greater mystery to man than was her sister of the ninth. Scientific conquests do but touch the periphery of her being; they explore her nature so far as it is of common quality and powers with the nature of man and of the feminine animals, and would perhaps do more wisely if they stopped dumb before what lies beyond and above these levels. For beyond, man reads but to misread—studies but to vex and confuse himself, and—shall I say it?—learns to sneer at rather than to reverence what baffles his inquiries. Does this statement seem harsh? Is it doubted? See its truth. The only science (so called) which undertakes a study of woman does not inspire its student with an increased respect for her. As a class, medical men, above that of other men, are perhaps less chivalrous than blacksmiths. Lucky is she and lucky are they if it be not diminished instead. For, assuming man as the standard, the corporeal functions, which absolutely elevate her in the scale of development, being added to all that he possesses, and constituting her corporeal womanhood, are seen by this student only as disabilities from which he is happily exempt (as if a disability could come into any life but through the door of an ability); and her larger measure of the divine attributes, faith, hope, and love—love, as compassion and as maternity—are seen as simple weaknesses to which he is happily superior.