Полная версия

Полная версияThe Continental Monthly, Vol. 3, No. 1 January 1863

By census table 36, p. 197, the value, in 1860, of the farm lands of all the Slave States, was $2,570,466,935, and the number of acres 245,721,062, worth $10.46 per acre. In the Free States, the value of the farm lands was $4,067,947,286, and the number of acres 161,462,008, worth $25.19 per acre. Now if, as certainly in the absence of slavery would have been the case, the farm lands of the South had been worth as much per acre as those of the North, their total value would have been $6,189,713,551, and, deducting the present price, the additional cash value would have been $3,619,346,616. Now the whole number of slaves in all the States, in 1860, was 3,950,531, multiplying which by $300, as their average value, would make all the slaves in the Union worth $1,185,159,300. Deduct this from the enhanced value of the farm lands of the South as above, and the result would be $2,434,087,316 as the gain in the price of farms by emancipation. This is independent of the increased value of their unoccupied lands, and of their town and city property.

By census tables of 1860, 33 and 36, the total value of the products of agriculture, mines, and fisheries in the Free States was $4,100,000,000, and of the Slave States $1,150,000,000, making the products of the Free States in 1860 nearly 4 to 1 of the Slave States, and $216 per capita for the Free States, and for the Slave States $94 per capita. This is exclusive of commerce, which would greatly increase the ratio in favor of the North, that of New York alone being nearly equal to that of all the Slave States. Now, multiply the population of the Slave States by the value of the products per capita of the Free States, and the result is $2,641,631,032, making, by emancipation, the increased annual product of the Slave States $1,491,631,032, and in ten years, exclusive of the yearly accumulations, $14,916,310,320.

By the table 35, census of 1860, the total value of all the property, real and personal, of the Free States, was $10,852,081,681, and of the Slave States, $5,225,307,034. Now, the product, in 1860, of the Free States, being $4,100,000,000, the annual yield on the capital was 38 per cent.; and, the product of the Slave States being $1,150,000,000, the yield on the capital was 22 per cent. This was the gross product in both cases. I have worked out these amazing results from the census tables, to illustrate the fact, that the same law, by which slavery retarded the progress of wealth in Virginia, as compared with New York, and of Maryland and South Carolina, as compared with Massachusetts, rules the relative advance in wealth of all the Slave States, as compared with that of all the Free States. I have stated that the statistics of commerce, omitted in these tables, would vastly increase the difference in favor of the Free States, as compared with the Slave States, and of New York as contrasted with Virginia. I shall now resume the latter inquiry, so as to complete the comparison between New York and Virginia. By commerce is embraced, in this examination, all earning not included under the heads of agriculture, manufactures, the mines, or fisheries.

Railroads.—The number of miles of railroads in operation in New York, in 1860, including city roads, was 2,842 miles, costing $138,395,055; and in Virginia, 1,771 miles, costing $64,958,807. (Census table of 1860, No. 38, pp. 230 and 233.) Now, by the same census report, p. 105, the value of the freights of the New York roads for 1860 was as follows: Product of the forest—tons carried, 373,424; value per ton, $20; total value, $7,468,480. Of animals—895,519 tons; value per ton, $200; total value, $179,103,800. Vegetable food—1,103,640 tons; value per ton, $50; total value, $55,182,000. Other agricultural products—143,219 tons; value per ton, $15; total value, $2,148,055. Manufactures—511,916 tons; value per ton, $500; total value, $391,905,500. Other articles—930,244 tons; value, $10 per ton; total value, $9,302,440. Grand total, 4,741,773 tons carried; value per ton, $163. Total values, $773,089,275. Deducting one quarter for duplication, makes 3,556,330 tons carried on the New York roads in 1860; and the value, $579,681,790. The values of the freights on the Virginia roads, as estimated, is $60,000,000, giving an excess to those of New York of $519,681,790, on the value of railroad freights in 1860. The passenger account, not given, would largely increase the disparity in favor of New York.

Canals.—The number of miles of canals in New York is 1,038, and their cost $67,567,972. In Virginia, the number of miles is 178, and the cost $7,817,000. (Census table 39, p. 238.) The estimated value of the freight on the New York canals is 19 times that of the freight on the Virginia canals. (Census.)

Tonnage.—The tonnage of vessels built in New York in 1860 was 31,936 tons, and in Virginia 4,372. (Census, p. 107.)

Banks.—The number of banks in New York in 1860 was 303; capital $111,441,320, loans $200,351,332, specie $20,921,545, circulation $29,959,506, deposits $101,070,273; and in Virginia the number was 65; capital $16,005,156, loans $24,975,792, specie $2,943,652, circulation $9,812,197, deposits $7,729,652. (Table 34, p. 193, Census.)

Insurance Companies.—The risks taken in New York were $916,474,956, or nearly one third of those in the whole Union. Virginia, estimated at $100,000,000; difference in favor of New York $816,474,956. (Census, p. 79.)

Exports and Imports, etc.—Our exports abroad from New York for the fiscal year ending 30th June, 1860, were $145,555,449, and the foreign imports $248,489,877; total of both, $394,045,326. The clearances same year from New York were 4,574,285 tons, and the entries 4,836,448 tons; total of both, 9,410,733 tons. In Virginia, the exports the same year were $5,858,024, and the imports $1,326,249; total of both, $7,184,273; clearances, 80,381 tons, entries, 97,762 tons; total of both, 178,143 tons. (Table 14, Register of United States Treasury.) Revenue collected from customs same year in New York, $37,788,969, and in Virginia $189,816, or 200 to 1 in favor of New York. (Tables, U.S. Com. of Customs.) No returns are given for the coastwise and internal trade of either State, but the tables of the railway and canal transportation of both States show nearly the same proportion in favor of New York as in the foreign trade. Thus the domestic exports from New York for the above year abroad were $126,060,967, and from Virginia $5,833,371. (Same table, 14.) And yet Virginia, as we have seen, had much greater natural advantages than New York for commerce, as well as for mines, manufactures, and agriculture. But slavery has almost expelled commerce from Virginia, and nearly paralyzed all other pursuits.

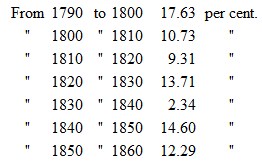

These tables, taken from the census and the Treasury records, prove incontestably, that slavery retards the progress of wealth and population throughout the South, but especially in Virginia. Nor can the Tariff account for the results; for Virginia, as we have seen, possesses far greater advantages than New York for manufactures. Besides, the commerce of New York far surpasses that of Virginia, and this is the branch of industry supposed to be affected most injuriously by high tariffs, and New York has generally voted against them with as much unanimity as Virginia. But there is a still more conclusive proof. The year 1824 was the commencement of the era of high tariffs, and yet, from 1790 to 1820, as proved by the census, the percentage of increase of New York over Virginia was greater than from 1820 to 1860. Thus, by table I of the census, p. 124, the increase of population in Virginia was as follows:

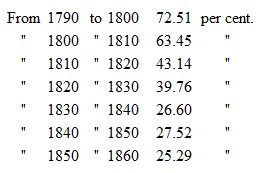

The increase of population in New York was:

In 1790 the population of Virginia was 748,318, in 1820, 1,065,129, and in 1860, 1,596,318. In 1790 the population of New York was 340,120, in 1820, 1,372,111, and in 1860, 3,880,735. Thus, from 1790 to 1820, before the inauguration of the protective policy, the relative increase of the population of New York, as compared with Virginia, was very far greater than from 1820 to 1860. It is quite clear, then, that the Tariff had no influence whatever in depressing the progress of Virginia as compared with New York.

We have heretofore proved by the census the same position as regards the relative progress of Maryland and Massachusetts, and the same principle applies as between all the Free, as compared with all the Slave States. In New York, we have seen that her progress from 1790 to 1820, in the absence of high tariffs, and, even before the completion of her great canal, her advance in population was much more rapid than from 1820 to 1860. Indeed, it is quite clear that, so far as the Tariff had any influence, it was far more unfavorable to New York than to Virginia, New York being a much greater agricultural as well as commercial State.

Having shown how much the material progress of Virginia has been retarded by slavery, let us now consider its effect upon her moral and intellectual development.

Newspapers AND Periodicals.—The number of newspapers and periodicals in New York in 1860 was 542, of which 365 were political, 56 religious, 63 literary, 58 miscellaneous; and the number of copies circulated in 1860 was 320,930,884. (Census tables, Nos. 15, 37.) The number in Virginia was 139; of which 117 were political, 13 religious, 3 literary, 6 miscellaneous; and the number of copies circulated in 1860 was 26,772,568. Thus, the annual circulation of the press in New York was twelve times as great as that of Virginia. As to periodicals: New York had 69 monthlies, of which 2 were political, 25 religious, 24 literary, and 18 miscellaneous; 10 quarterlies, of which 5 were religious, and 5 literary; 6 annuals, of which 2 were political, 2 religious, and 2 miscellaneous. Virginia had 5 monthlies, of which 1 was political, 2 religious, 1 literary, and 1 miscellaneous; and no quarterlies or annuals. The annual circulation of the New York monthlies was 2,045,000; that of Virginia was 43,900; or more than 43 to 1 in favor of New York.

As regards schools, colleges, academies, libraries, and churches, I must take the census of 1850, those tables for 1860 not being yet arranged and printed. The number of public schools in New York in 1850 was 11,580, teachers 13,965, pupils 675,221; colleges, academies, etc., pupils 52,001; attending school during the year, as returned by families, 693,329; native adults of the State who cannot read or write, 23,341. Public libraries, 11,013; volumes, 1,760,820. Value of churches, $21,539,561. (Comp. Census, 1850.)

The number of public schools in Virginia in 1850 was 2,937, teachers 3,005, pupils 67,438; colleges, academies, etc., pupils 10,326; attending school during the year, as returned by families, 109,775; native white adults of the State who cannot read or write, 75,868. Public libraries, 54; volumes, 88,462. Value of churches, $2,902,220. (Compend. of Census of 1850.) By table 155, same compend, the percentage of native free population in Virginia over 20 years of age who cannot read or write is 19.90, and in New York 1.87, in North Carolina 30.34, in Maryland 11.10, in Massachusetts 0.32, or less than one third of one per cent. In New England, the percentage of native whites who cannot read or write is 0.42, or less than one half of one per cent.; and in the Southern States 20.30, or 50 to 1 in favor of New England. (Compend., table 157.) But, if we take the whole adult population of Virginia, including whites, free blacks, and slaves, 42.05 per cent., or nearly one half, cannot read or write; and in North Carolina, more than one half cannot read or write. We have seen, by the above official tables of the census of 1850, that New York, compared with Virginia, had nearly ten times as many pupils at schools, colleges, and academies, twenty times as many books in libraries, and largely more than seven times the value of churches; while the ratio of native white adults who cannot read or write was more than 10 to 1 in Virginia, compared with New York. We have seen, also, that in North Carolina nearly one third of the native white adults, and in Virginia nearly one fifth, cannot read or write, and in New England 1 in every 400, in New York 1 in every 131, in the South and Southwest 1 in every 12 of the native white adults. (Comp. p. 153.)

These official statistics enable me, then, again to say that slavery is hostile to the progress of wealth and education, to science and literature, to schools, colleges, and universities, to books and libraries, to churches and religion, to the press, and therefore to free government; hostile to the poor, keeping them in want and ignorance; hostile to labor, reducing it to servitude, and decreasing two thirds the value of its products; hostile to morals, repudiating among slaves the marital and parental condition, classifying them by law as chattels, darkening the immortal soul, and making it a crime to teach millions of human beings to read or write. Surely such a system is hostile to civilization, which consists in the education of the masses of the people of a country, and not of the few only. A State, one third of whose population are slaves, classified by law as chattels, and forbidden all instruction, and nearly one fifth of whose adult whites cannot read or write, is semi-civilized, however enlightened may be the ruling classes. If a highly educated chief or parliament governed China or Dahomey, they would still be semi-civilized or barbarous countries, however enlightened their rulers might be. The real discord between the North and the South, is not only the difference between freedom and slavery, but between civilization and barbarism caused by slavery. When we speak of a civilized nation, we mean the masses of the people, and not the government or rulers only. The enlightenment of the people is the true criterion of civilization, and any community that falls below this standard, is barbarous or semi-civilized. In countries where kings or oligarchies rule, the government may be maintained, (however unjustly,) without educating the masses; but, in a republic, or popular government, this is impossible; and the deluded masses of the South never could have been driven into this rebellion, but for the ignorance into which they had been plunged by slavery; nor is there any remedy for the evil but emancipation. If, then, we would give stability and wisdom to the government, and perpetuity to the Union, we must abolish slavery, which withholds education and enlightenment from the masses of the people, who, with us, control the policy of the nation.

With our only cause of ignorance and poverty among the people, and only element of discord among the States, extirpated by the gradual removal of slavery and negroism, we would bound forward in a new and wonderful career of power and prosperity. Our noble vessel of state, the great Republic, freighted with the hopes of humanity, and the liberties of our country and of mankind, still bearing aloft the flag of our mighty Union, indissoluble by domestic traitors or conspiring oligarchs, will, under Divine guidance, pass over the troubled waters, reassuring a desponding world, as she glides into the blessed haven of safety and repose. All the miracles of our past career would be eclipsed by the glories of the future. We might then laugh to scorn the impotent malice of foreign foes. Without force or fraud, without sceptre or bayonet, our moral influence and example, for their own good, and by their own free choice, would control the institutions and destiny of nations. The wise men of the East may then journey westward again, to see the rising star of a regenerated humanity, the fall of thrones and dynasties, the lifting up of the downtrodden masses, and the political redemption of our race, not by a new dispensation, but by the fulfilment thus of the glorious prophecies and blessed promises of Holy Writ. And can we not lift ourselves into that serene atmosphere of love of country and of our race, above all selfish schemes or mere party devices, and contemplate the grandeur of these results, if now, now, NOW we will only do our duty? Now, indeed, is the 'accepted time,' now is the day of the 'salvation' of our country. And now, as in former days of trouble, let us remember the mighty dead, as, when living, silencing the voice of treason, and calming the tempest of revolution, he uttered those electric words: 'Union and Liberty, now and forever, one and inseparable!'

If we could rise to the height of prophetic vision, behold the procession of coming events, and, unrolling the scroll of advancing years and centuries, contemplate our Union securing by its example the rights and liberties of man, would we not welcome any sacrifice, even death itself, if we could thus aid in accomplishing results so god-like and sublime? But, whether in gloom or glory, chastened for national sins or rewarded for good deeds, let us realize the great truth, that the Almighty directs nations as well as planets in their course, governs the moral as well as the material world, never abdicating for a moment the control of either; and that persevering opposition to his laws must meet, in the end, retributive justice.

PROMISE

O watcher for the dawn of day,As o'er the mountain peaks afarHangs in the twilight cold and gray,Like a bright lamp, the morning star!Though slow the daybeams creep alongThe serried pines which top the hills,And gloomy shadows brood amongThe silent valleys, and the rillsSeem almost hushed—patience awhile!Though slowly night to day gives birth,Soon the young babe with radiant smileShall gladden all the waiting earth.By fair gradation changes come,No harsh transitions mar God's plan,But slowly works from sun to sunHis perfect rule of love to man.And patience, too, my countrymen,In this our nation's fierce ordeal!Bright burns the searching flame, and then,The dross consumed, shall shine the real.Wake, watcher! see the mountain peaksAlready catch a golden ray,Light on the far horizon speaksThe dawning of a glorious day.Murky the shadows still that clingIn the deep valleys, but the mistIs soaring up on silver wingTo where the sun the clouds has kissed.Hard-fought and long the strife may be,The powers of wrong be slow to yield,But Right shall gain the victory,And Freedom hold the battle field.AMERICAN DESTINY

We would study the question of American Destiny in the light of common sense, of history, and of science.

It may be unusual to illustrate from science a principle which is to have a political application; but we shall endeavor to do so, believing it to be unexceptionably legitimate. The different departments of science, science and history, science and politics, have been, heretofore, kept quite distinct as to the provinces of inquiry to which it was presumed they severally belonged. Each has been cultivated as if it had no relation external to itself, and was not one of a family of cognate truths. This, however, is undergoing a gradual but certain change, in which it is becoming constantly more manifest that between the different departments of human inquiry there are mutual dependences and complicated interrelations, which enable us, by the truths of one science, to thread the mazes of another.

There are certain general laws which pertain with equal validity to many departments of activity in the natural world; there are parallel lines of development as the result of the inherent correlation of forces. Thus, if we have found a great general law in physiology, that same law may apply with equal aptness to astronomy, geology, chemistry, and even to social and political evolution.

One of these general laws, and perhaps the most comprehensive in its character and universal in its application of any yet known, we will announce in the language of Guyot, the comparative geographer: 'We have recognized in the life of all that develops itself, three successive states, three grand phases, three evolutions, identically repeated in every order of existence; a chaos, where all is confounded together; a development, where all is separating; a unity, where all is binding itself together and organizing. We have observed that here is the law of phenomenal life, the formula of development, whether in inorganic nature or in organized nature.'

This answers for the department of physics and physiology. We will let Guizot, the historian, speak for the political and social realm: 'All things, at their origin, are nearly confounded in one and the same physiognomy; it is only in their aftergrowth that their variety shows itself. Then begins a new development which urges forward societies toward that free and lofty unity, the glorious object of the efforts and wishes of mankind.'

We find an illustration of this law in the simplest of the sciences, if the nebular hypothesis be true, as most astronomers believe. We have first the chaotic, nebulous matter, then the formation of worlds therefrom, by a continuous process of unfolding. Each world is a unit within itself, but part of a still greater unit composed of a system of worlds revolving around the same sun; and this greater unit, part of one which is still greater—a star cluster, composed of many planetary systems, and subject to the same great cosmical laws. If the theory be correct, we find, in this example, the heterogeneous derived from the simple, and far more completely an organized unit, with all its complexity, than was the chaotic mass from which development originally proceeded.

We find additional illustration in coming to our own world. Its primeval geography was simple and uniform; there was little diversity of coast line, soil, or surface. But the cooling process of the earth went on, the surface contracted and ridged up, the exposed rocks were disintegrated by the action of the atmosphere and the waters; the sediment deposited in the bottom of the seas was thrown to the surface; continents were enlarged, higher mountain ranges upheaved, the coasts worn into greater irregularity of outline; and everywhere the soil became more composite, the surface more uneven, the landscape more variegated.

Corresponding changes have taken place in the climate. At first the temperature of the earth was much warmer than now, and uniform in all parallels of latitude, as is shown by the fossil remains. Now we have a great diversity of climate, whether we contrast the polar with the torrid regions, or the different seasons of the temperate zone with each other.

The same law of increasing diversity obtains in the fauna and flora of the various periods of geological history. The earliest fossil record of animal life is witness to the simplicity of organic structure. Among vertebrated animals, fishes first appear, next reptiles, then birds; still higher, the lower type of animals which suckle their young; and as the strata become more recent, still higher forms of mammalia, till we reach the upper tertiary, in which geologists have discovered the remains of many animals of complex structure nearly allied to those which are now in existence. In the historic period appear many organic forms of still greater complexity, with man at the head of the zoological series.

In this glance of zoological progress, we discover increasing complication of two kinds; for while the individual structure has been constantly becoming more complex, there are now in existence the analogues of the lowest fossil types, which, with the highest, and with all the intermediate, present a maze and vastness of complication, which, in comparison with the homogeneity of the aggregate of early structure, is sufficiently obvious and impressive.

There is in this view, still another outline of increasing complexity. At first the same types prevailed all over the earth's surface; but as the soil, atmosphere, and climate changed, and the animal structure became more complex and varied, the limits of particular species became more and more localized, till the earth's surface presented zoological districts, with the fauna of each peculiar to itself.

But, what of unitization? Here, there appears to be divergence only, and that continually increasing.

Guyot says that 'the unity reappears with the creation of man, who combines in his physical nature all the perfections of the animal, and who is the end of all this long progression of organized beings.' Agassiz recognizes man alone as cosmopolite; and Comte regards him as the supreme head of the economy of nature, and representative of the fundamental unity of the anatomical scale.