Полная версия

Полная версияThe Bay State Monthly. Volume 1, No. 5, May, 1884

The advance of the British army was like a solemn pageant in its steady headway, and like a parade for inspection in its completeness. This army, bearing knapsacks and full campaign equipment, moved forward as if, by the force of its closely knit columns, it must sweep every barrier away. But, right in the way was a calm, intense love of liberty. It was represented by men of the same blood and of equal daring.

A strong contrast marked the opposing Englishmen that summer afternoon. The plain men handled plain firelocks. Oxhorns held their powder, and their pockets held their bullets. Coatless, under the broiling sun, unincumbered, unadorned by plume or service medal, pale and wan after their night of toil and their day of hunger, thirst, and waiting, this live obstruction calmly faced the advancing splendor.

A few hasty shots, quickly restrained, drew an innocent fire from the British front rank. The pale, stern men behind the slight defence, obedient to a strong will, answer not to the quick volley, and nothing to the audible commands of the advancing columns,—waiting, still.

No painter can make the scene more clear than the recital of sober deposition, and the record left by survivors of either side. History has no contradictions to confuse the realities of that momentous tragedy.

The British left wing is near the redoubt. It has only to mount a fresh earthbank, hardly six feet high, and its clods and sands can almost be counted,—it is so near, so easy—sure.

Short, crisp, and earnest, low-toned, but felt as an electric pulse, are the words of Prescott. Warren, by his side, repeats. The words fly through the impatient lines. The eager fingers give back from the waiting trigger. "Steady, men." "Wait until you see the white of the eye." "Not a shot sooner." "Aim at the handsome coats." "Aim at the waistbands." "Pick off the commanders." "Wait for the word, every man,—steady."

Those plain men, so patient, can already count the buttons, can read the emblems on the breastplate, can recognize the officers and men whom they had seen parade on Boston Common. Features grow more distinct. The silence is awful. The men seem dead—waiting for one word. On the British right the light infantry gain equal advance just as the left wing almost touched the redoubt. Moving over more level ground, they quickly made the greater distance, and passed the line of those who marched directly up the hill. The grenadiers moved firmly upon the centre, with equal confidence, and space lessens to that which the spirit of the impending word defines. That word waits behind the centre and left wing, as it lingers at breastwork and redoubt. Sharp, clear, and deadly in tone and essence, it rings forth,—Fire!

THE REPULSE

From redoubt to river, along the whole sweep of devouring flame, the forms of men wither as in a furnace heat. The whole front goes down. For an instant the chirp of the cricket and grasshopper in the fresh-mown hay might almost be heard; then the groans of the wounded, then the shouts of impatient yeomen who spring forth to pursue, until recalled to silence and duty. Staggering, but reviving, grand in the glory of their manhood, heroic in restored self-possession, with steady step in the face of fire, and over the bodies of the dead, the British remnant renew battle. Again, a deadly volley, and the shattered columns, in spite of entreaty or command, speed back to the place of landing, and the first shock of arms is over.

A lifetime, when it is past, is but as a moment. A moment, sometimes, is as a lifetime. Onset and repulse. Three hundred lifetimes ended in twenty minutes.

Putnam hastened to Bunker Hill to gather scattering parties in the rear and urge coming reinforcements across the isthmus, where the fire from British frigates swept with fearful energy, but nothing could bring them in time. The men who had toiled all night, and had just proved their valor, were again to be tested.

The British reformed promptly, in the perfection of their discipline. Their artillery was pushed forward nearer the angle made by the breastwork next the redoubt, and the whole line advanced, deployed as before, across the entire American front. The ships-of-war increased their fire across the isthmus. Charlestown had been fired, and more than four hundred houses kindled into one vast wave of smoke and flame, until a sudden breeze swept its quivering volume away and exposed to view of the watchful Americans the returning tide of battle. No scattering shots in advance this time. It is only when a space of hardly five rods is left, and a swift plunge could almost forerun the rifle flash, that the word of execution impels the bullet, and the entire front rank, from redoubt to river, is swept away. Again, and again, the attempt is made to rally and inspire the paralyzed troops; but the living tide flows back, even to the river.

Another twenty minutes,—hardly twenty-five,—and the death angel has gathered his sheaves of human hopes, as when the Royal George went down beneath the waters with its priceless value of human lives.

At the first repulse the thirty-eighth regiment took shelter by a stone fence, along the road which passes about the base of Breed's Hill; but at the second repulse, supported by the fifth, it reorganized, just under the advanced crest of Breed's Hill for a third advance.

It was an hour of grave issues. Burgoyne, who watched the progress from Copp's Hill, says: "A moment of the day was critical."

Stedman says: "A continuous blaze of musketry, incessant and destructive."

Gordon says: "The British officers pronounced it downright butchery to lead the men afresh against those lines."

Ramsay says: "Of one company not more than five, and of another not more than fourteen, escaped."

Lossing says: "Whole platoons were lain upon the earth, like grass by the mower's scythe."

Marshall says: "The British line, wholly broken, fell back with precipitation to the landing-place."

Frothingham quotes this statement of a British officer: "Most of our grenadiers and light infantry, the moment they presented themselves, lost three fourths, and many nine tenths, of their men. Some had only eight and nine men to a company left, some only three, four, and five."

Botta says: "A shower of bullets. The field was covered with the slain."

Bancroft says: "A continuous sheet of fire."

Stark says: "The dead lay as thick as sheep in a fold."

It was, indeed, a strange episode in British history, in view of the British assertion of assured supremacy, whenever an issue challenged that supremacy.

Clinton and Burgoyne, watching from the redoubt on Copp's Hill, realized at once the gravity of the situation, and Clinton promptly offered his aid to rescue the army.

Four hundred additional marines and the forty-seventh regiment were promptly landed. This fresh force, under Clinton, was ordered to flank the redoubt and scale its face to the extreme left. General Howe, with the grenadiers and light infantry, supported by the artillery, undertook the storming of the breastworks, bending back from the mouth of the redoubt, and so commanding the centre entrance.

General Pigot was ordered to rally the remnants of the fifth, thirty-eighth, forty-third, and fifty-second regiments, to connect the two wings, and attack the redoubt in front.

A mere demonstration was ordered upon the American left, while the artillery was to advance a few rods and then swing to its left, so as to sweep the breastwork for Howe's advance.

THE ASSAULT

The dress parade movement of the first advance was not repeated. A contest between equals was at hand. Victory or ruin was the alternative for those who so proudly issued from the Boston barracks at sunrise for the suppression of pretentious rebellion. Knapsacks were thrown aside. British veterans stripped for fight. Not a single regiment of those engaged had passed such a fearful ordeal in its whole history as a single hour had witnessed. The power of discipline, the energy of experienced commanders, and the pressure of honored antecedents, combined to make the movement as trying as it was momentous.

The Americans were no less under a solemn responsibility. At the previous attack, some loaded while others fired, so that the expenditure of powder was great, almost exhaustive. The few remaining cannon cartridges were economically distributed. There was no longer a possibility of reinforcements. The fire from the shipping swept the isthmus. There were less than fifty bayonets to the entire command.

During the afternoon Ward sent his own regiment, as well as Patterson's and Gardner's, but few men reached the actual front in time to share in the last resistance. Gardner did, indeed, reach Bunker Hill to aid Putnam in establishing a second line on that summit, but fell in the discharge of the duty. Febiger, previously conspicuous at Quebec, and afterward at Stony Point, gathered a portion of Gerrishe's regiment, and reached the redoubt in time to share in the final struggle; but the other regiments, without their fault, were too late.

At this time, Putnam seemed to appreciate the full gravity of the crisis, and made the most of every available resource to concentrate a reserve for a second defence, but in vain.

Prescott, within the redoubt, at once recognized the method of the British advance. The wheel of the British artillery to the left after it passed the line of the redoubt, secured to it an enfilading fire, which insured the reduction of the redoubt and cut off retreat. There was no panic at that hour of supreme peril. The order to reserve fire until the enemy was within twenty yards was obediently regarded, and it was not until a pressure upon three faces of the redoubt forced the last issue, that the defenders poured forth one more destructive volley. A single cannon cartridge was distributed for the final effort, and then, with clubbed guns and the nerve of desperation, the slow retreat began, contesting, man to man and inch by inch. Warren fell, shot through the head, in the mouth of the fort.

The battle was not quite over, even then. Jackson rallied Gardner's men on Bunker Hill, and with three companies of Ward's regiment and Febiger's party, so covered the retreat as to save half of the garrison. The New Hampshire troops of Stark and Reed, with Colt's and Chester's companies, still held the fence line clear to the river, and covered the escape of Prescott's command until the last cartridge had been expended, and then their deliberate, well-ordered retreat bore testimony alike to their virtue and valor.

THE END

Putnam made one final effort at Bunker Hill, but in vain, and the army retired to Prospect Hill, which Putnam had already fortified in advance.

The British did not pursue, Clinton urged upon General Howe an immediate attack upon Cambridge; but Howe declined the movement. The gallant Prescott offered to retake Bunker Hill by storming if he could have three fresh regiments; but it was not deemed best to waste further resources at the time.

Such, as briefly as it can be clearly outlined, was the battle of Bunker Hill.

Nearly one third of each army was left on the field.

The British loss was nineteen officers killed and seventy wounded, itself a striking evidence of the prompt response to Prescott's orders before the action began. Of rank and file, two hundred and seven were killed and seven hundred and fifty-eight were wounded. Total, ten hundred and fifty-four.

The American loss was one hundred and forty-five killed and missing, and three hundred and four wounded. Total, four hundred and forty-nine.

Such is the record of a battle which, in less than two hours, destroyed a town, laid fifteen hundred men upon the field, equalized the relations of veterans and militia, aroused three millions of people to a definite struggle for National Independence, and fairly opened the war for its accomplishment.

NOTES

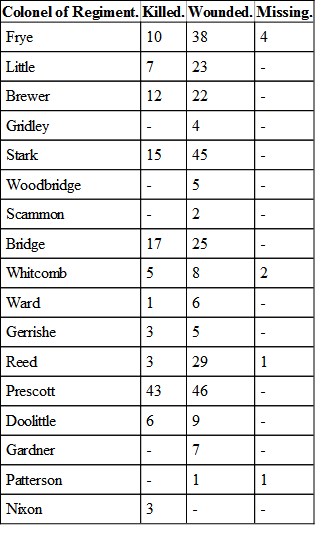

NOTE 1. The hasty organization of the command is marked by one feature not often regarded, and that is the readiness with which men of various regiments enlisted in the enterprise. Washington, in his official report of the casualties, thus specifies the loss:—

NOTE 2. The record, brief as it is, shows that hot controversies as to the question of precedence in command are beneath the merits of the struggle, because all worked just where the swift transitions of the crisis best commanded presence and influence.

NOTE 3. As both the Morton and Moulton families had property near the British landing-place, it is immaterial whether hill or point bear the name of one or the other. Hence the author of this sketch, in a memorial examination of this battle, elsewhere, deemed it but just to recognize both, without attempt to harmonize differences upon an immaterial matter.

NOTE 4. The occupation of Lechmere Point, Cobble Hill, Ploughed Hill, and Prospect Hill, as shown upon the map of Boston and vicinity, rendered the British occupation of Bunker Hill a barren victory, silenced the activity of a thousand men, vindicated the wisdom of the American occupation, however transient, rescued Boston, and projected the spirit of the battle of Bunker Hill into all the issues which culminated at Yorktown, October 19, 1781.

THE YOUNG MEN'S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF MASSACHUSETTS

By Russell Sturgis, JrIn the sketch of the Boston Association, which appeared in the April number of this Magazine, mention was made of the work of Mr. L.P. Rowland, corresponding member of Massachusetts of the international committee, in establishing kindred associations throughout the State, This article is to give a brief history of the spread and work of these associations, and I am largely indebted to Mr. Sayford, late state secretary, for the data. It was natural that as soon as it was known that an organization had been formed in Boston to do distinctive work for young men, that in other places where the need was realized the desire for a like work should spring up; but, in the absence of organized effort to promote this, very little was done, and in 1856, five years after the parent association was formed, there were only six in all, that is, in Boston, Charlestown, Worcester, Lowell, Springfield, and Haverhill.

In December, 1866, the Boston Association called a convention, when twelve hundred delegates met and sat for two days at the Tremont Temple. General Christian work was discussed, but the distinctive work for young men was earnestly advocated.

When Mr. Rowland undertook the work, as an officer of the international committee, it spread rapidly, and in 1868 there were one hundred and two, and in 1869, one hundred and nine, associations in Massachusetts. This number was, later, somewhat further increased.

Up to 1867 there had been no conference of the state associations, but at the international convention, at Montreal, in that year, it was strongly urged upon the corresponding members of the various States and provinces that they should call state conventions, and thus the first Massachusetts convention of Young Men's Christian Associations was held at Springfield, October 10 and 11. The Honorable Whiting Griswold, of Greenfield, was president, and among the prominent men present were Henry F. Durant and ex-Vice-President Wilson. In 1868, the convention met at Worcester; in 1869, at Lowell. At this time there were fifty associations reporting reading-rooms, and thirty were holding open-air meetings, which means, that, since there are many persons who never enter a building to hear the gospel, it should be taken to them. Since these services are almost peculiarly a characteristic of association work, let me describe them. One or two men, clergymen or laymen, are appointed to take charge of the meeting, while from six to ten men go with them to lead the singing. Having reached the common or public square where men and women are lounging about, the group start a familiar hymn and sing, perhaps, two or three, by which time many have drawn near and most are listening; then mounting a bench or packing-box, the leader says he proposes to pray to the God of whom they have been singing, and asks them to join with him; then with uncovered head he speaks to God and asks him to bless the words that shall be spoken. Another hymn, and then some Bible scene or striking incident is read and commented upon, and when interest is fairly roused the gospel is preached in its simplicity and a direct appeal made to the people. There is a wonderful fascination in this service—a naturalness in all the surroundings, so like the circumstances of our Lord's discourses, that makes God's nearness felt, and inspires great faith for results. Great have been these results—how great we shall know by-and-by. Many a soul has thus been born by the sea, in the grove, on the village green, at the place where streets meet in the busy city. How can we reach the masses? is the earnest question of the church. Go to them! To the association is due the fact that thousands of laymen are to-day proclaiming the gospel in all parts of the world, successful through their simple study of the Word and the encouragement and training which they have received in this school.

The fourth convention was held in Chelsea, in 1870, on which occasion the Honorable Cephas Brainard, chairman of the international executive committee, said: "To promote the permanency of associations, our labor must be chiefly for young men; increasing as rapidly as possible edifices of our own; and cultivating frequent fraternal intercourse with the eight hundred associations in the land." Up to 1881 no agents had been appointed by the state convention to superintend its work. Mr. Rowland was taking time, given him for rest, to visit associations and towns needing them.

At the international convention, in 1868, at Detroit, two Massachusetts men met, who were to be largely instrumental in carrying on the work in the State so dear to them; and in 1871, in far-off Illinois, these two men—K.A. Burnell, and he who has almost without a break served on the Massachusetts committee to this day—met again, prayed for Massachusetts, consulted together, and the result was that at the convention of 1871, at Northampton, a state executive committee was appointed.

At this time calls from many parts of the State were coming to the association workers from pastors of churches for lay help and they felt that these calls must be met. Mr. Burnell was engaged to conduct the work, and with the help of the committee individually, meetings of two and three days were held in from forty to sixty towns each year for three years. This work was continued by paid secretaries, still largely aided by the committee, till 1879.

During this time but little was done to strengthen existing associations, and nothing in establishing new ones, therefore, while the influence of the convention of associations was greatly felt throughout the State, the associations themselves suffered. Very many were doing nothing, and many had ceased to exist.

We should not dare to say that the associations did wrong in thus giving themselves to the evangelistic work, while the calls for it were greater than the committee could meet. This work engrossed them till the calls began to slacken, and then they awoke to the fact that they were neglecting their true work, a special instrumentality in which they believed and for which they existed—that is, "A work for young men by young men through physical, social, mental, and spiritual appliances."

This led to a series of resolutions at the Lowell convention, in 1879, directing the committee to confine their efforts to the strengthening and organizing of associations, and to appoint a secretary to give his whole time to the work.

Mr. Sayford was called from New York, appointed general secretary, and began to work in January, 1880.

At this time there were thirty-five associations in the State, only four of which had general secretaries, paid men who gave all their time to the work.

In October, the number of secretaries had more than doubled, nine being at work. The total membership at this time was, in round numbers, six thousand, with property amounting to about two hundred and ten thousand dollars.

The thirty-three associations which reported at this time at the Lynn convention represented somewhat more than five hundred active working men, and they conducted one hundred and ten religious meetings a week.

In 1881, the only addition of note was the beginning of the railway work in the State, when a general secretary was employed, and rooms opened at Springfield by the Boston and Albany Railroad Company. This important work, carried on most vigorously at various railway centres in other States, had for some time been pressed upon the state committee, but they had been unable to obtain any footing till now. At the convention of this year, at Spencer, the advantage of association work in colleges was brought out in an able paper by our present state secretary, then a representative of Williams College.

At this convention the committee on executive committee's report said: "It is evident from the reports of executive committee and state secretary, that, while the process of the last two years has decreased the number of the associations in the State, it has greatly increased their efficiency. Some associations were found to have been long since privately buried, though the name was allowed to remain upon the door. These have been removed. Others had been left to die uncared for in the field. These have been decently buried. Some were found so sick as to be past hope, and their last days were made as comfortable as possible under the circumstances. Others were found to be more or less seriously ill, and have been skilfully treated. The result is that at least twenty-four associations are well, and could do much more work if they chose; while ten, in robust condition, and under the management and inspiration of skilled general secretaries, are doing grand work for young men in their several localities."

The reduction here spoken of is from one hundred and nine associations in 1869 to thirty-four in 1881; yet the work was being better done by the smaller number, and it is thus accounted for: Few dreamed to what this work would grow, therefore their aim was extremely vague, and the methods were inadequate. Seeing the need,—deeply interested in the salvation of young men,—the idea of the association took everywhere. They sprang up all over the State. Organization followed organization in rapid succession, and then they waited to be told what to do, or flung themselves into the first seeming opening with no thought whether it was the work for which they were formed; and we remember of hearing of one Young Men's Christian Association whose whole energies were concentrated upon a mission Sunday-school in a deserted district,—a good work, but not a proper Young Men's Christian Association's work, when it represented all that was being done.

Two things, however, were accomplished, even in those early days, for which we must always be very grateful, and in themselves are a sufficient raison d'etre. Young men were trained to work, and the reflex influence upon their minds was very great, and the real unity of the church of Christ was manifested as never before. The Young Men's Christian Association in town and village formed the natural rallying-point for all united work. A third great blessing should be mentioned. Not only has the unity of Christ's church been manifested, but also its distinctive standing upon the great Bible doctrines of the cross, which vitally separate it from all other religious bodies.

Gradually the greatness of this work for young men has been appreciated, as the strong opposing forces have been met. The association is intended to influence those who are in the energy and full flush of young manhood, when the desires are strong, most responsive, and least guarded. The social instinct then is very strong. It is natural, and must be met in some form. Sinful allurements of every kind invite the young man, hurtful companionship welcomes him, the ordinary appliances of the church have no attraction for him. The association must see to it that his social craving is met by that which is interesting enough to attract him, and yet is safe. To counteract baleful attractions, others which call forth strong sympathy, and appliances which cost, in every sense of the word, must be furnished.