Полная версия

Полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 17, No. 103, May, 1866

"The diffuseness of the present revenue system of the United States is doubtless one of its greatest imperfections, and under it the exemption of any article from taxation is the exception rather than the rule. To assert this, however, is no reflection on the judgment or skill of its authors. The system was framed under circumstances of such pressing necessity as to afford but little opportunity for any careful and accurate investigation of the sources of revenue; but it has most certainly accomplished the end designed, namely, the raising of revenue; and the country to-day is undoubtedly receiving by taxation far more revenue than is necessary for its legitimate expenditures. As a success, therefore, our present revenue system is a most honorable testimonial, not only to the wisdom of its authors, but to the patriotism of the people, who not only endured, but welcomed, the burdens it imposed upon them.

"A system of taxation, however, so diffuse as the present one, necessarily entails a system of duplication of taxes, which in turn leads to an undue enhancement of prices; a decrease both of production and consumption, and consequently of wealth; a restriction of exportations and of foreign commerce; and a large increase in the machinery and expense of the revenue collection.

"In respect to the injurious influence of this duplication of taxes upon the industry of the country, the Commission cannot speak too strongly. Its effect has already been most injurious. It threatens the very existence (even with the protection of inflated prices and a high tariff) of many branches of industry; and with a return of the trade and currency of the country to anything approximating its normal condition, it must, by checking development, prove highly disastrous.

"The influence of the duplication of taxes in sustaining prices is also, in the opinion of the Commission, far greater than those not conversant with the subject generally estimate; and were the price of gold and of the national currency made at once to approximate, and the present revenue system to continue unchanged, it would be impossible for the prices of most products of manufacturing industry to return to anything like their former level."

The Commission arrive at the conclusion, that all our manufactures are by these taxes increased in cost from ten to twenty per cent. In the language of Senator Sherman, when defending the Internal Tax Bill in the Senate last year, the nation required funds to maintain its armies in the field; it had put forth its arms and grasped the money of the country, and would reduce and equalize the taxes when the war was ended. The Revenue Commission find the taxes on our manufactures and their materials an incubus upon the industry and a check to the progress of the country, and recommend their remission. And this we may reasonably expect from Congress at its present session. But, it may be urged, how are we to meet the interest on our debt and current expenses of $284,000,000 in the aggregate, if we repeal these taxes? The answer is a simple one. The Commission estimate our imports at $400,000,000, and our duties now average forty-seven per cent. Should this continue, we should draw from this source alone $188,000,000. There is also the revenue from public lands and miscellaneous sources, which the Secretary and the Revenue Commission both rate at $21,000,000, making an aggregate of $209,000,000; although the Commission, to guard against the effects of any change in the tariff, modestly rate these items at only $151,000,000.

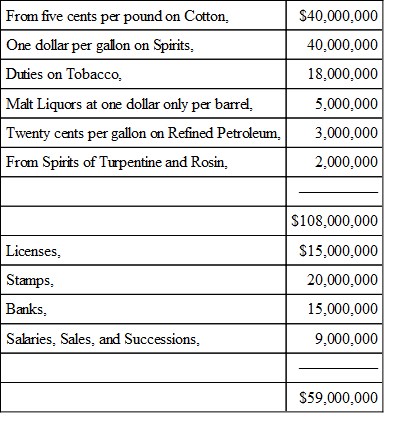

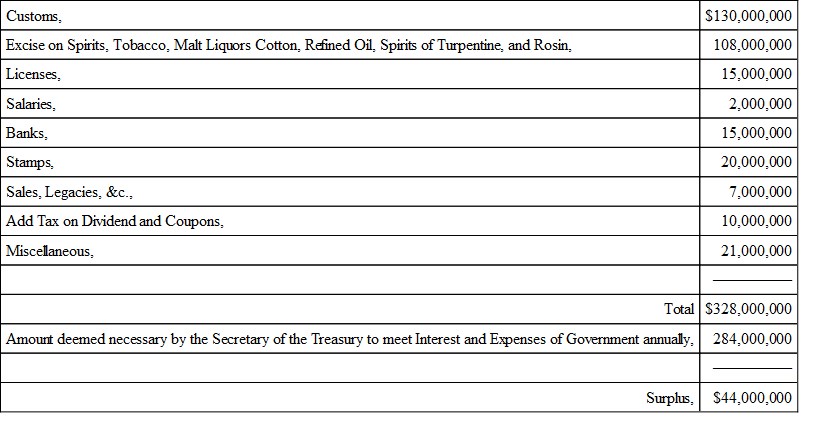

To these they add for excise, viz.:—

They thus provide a revenue of $318,000,000, or $30,000,000 more than that required by the Secretary,—a surplus which, with the annual excess of duties, to say nothing of the future growth of revenue, would extinguish our debt in little more than thirty years. But to guard against all contingencies, they propose to levy on incomes taxes to the amount of $40,000,000; and on the gross receipts of railways, bridges, canals, and stages, $9,000,000. These change the aggregate to $367,000,000; an excess of $81,000,000 over the estimate of our requirements by the Secretary.

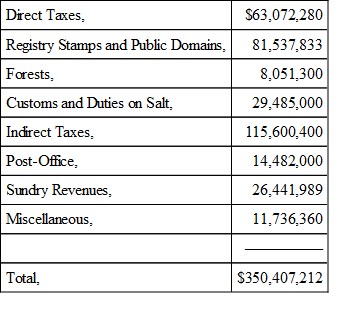

The Commission give us the Budget of France in the following summary, viz.:—

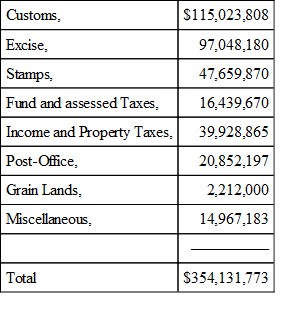

Also, the revenues of Great Britain and Ireland for 1865, viz.:—

If from these returns we deduct the earnings of the Post-Office Department, which are not included in the Commission's estimate of revenue for the United States, that estimate will exceed the returns of revenue for France or the United Kingdom by more than thirty millions, although the expenses of each of these countries are at least fifty millions more than the computed expenses of our own. It is obvious, therefore, from the Report of the Commission, that we may dispense with the fifty-nine millions from income tax and the duties on transportation, and still have a margin of more than thirty millions to cover contingencies and provide for the gradual reduction of the debt. Such a victory in finance achieved the first year after the war would give us a second great national triumph.

The system proposed by the Commission is entitled to the most favorable consideration. The taxes levied during the war were multifarious in their character. Although effective in producing revenue, they were imposed without discrimination, and they bear heavily alike both on producer and consumer, checking the industry of the one and swelling unduly the expenditures of the other. The plan of the Commission strikes the handcuffs from industry, lessens the expenses of collection, enables our artisan to compete with the foreigner, and, as most of the manufactures of the country are consumed at home, consequently reduces the cost of living. It seems from the Report of the Commission, that their leading idea is to simplify the system and reduce the number of taxes; to shift them from the producer to the consumer, and thus stimulate the creation of wealth; to diminish charges, and at the same time lighten the weight of the impost as it falls on the consumer. Another leading idea is to transfer a portion of our burdens to the foreign consumers of cotton, and at the same time stimulate our manufactures, and the production of cotton, by a remission of the tax on cloth exported; while yet another part of their plan was to take from the illicit trader and give to the public coffers the profit he now realizes upon spirits, and to restore alcohol to the arts.

Let us give to each of these measures the attention it deserves; and inquire if we may not take at once the steps, which the Commission defer for the present, toward the discontinuance of all charges upon transportation and incomes. In recommending the entire removal of taxes on production as the first measure to be adopted, the Commissioners advise: "That the capital stock of the country in the interval between 1850 and 1860, deducting the value of the slaves, increased at the rate of 158 per cent, or from $5,533,000 to $14,282,000; and that, if a development in any degree approximating to the past can be maintained and continued, then the extinguishment of the national debt in a comparatively brief period becomes a matter of no uncertainty. To secure this development, both by removing the shackles from industry, and by facilitating the means of rapid and cheap intercommunication between the different sections of the country, is to effect at the same time a solution of all the financial difficulties that now press upon us."

The policy of the Commission is the speedy abolition or reduction of all taxes which tend to check development. This policy is eminently wise and statesman-like; for while it removes some of our most onerous burdens, it gives a stimulus to the creation of wealth that must annually alleviate our taxes, and is entitled to the approval of an enlightened nation.

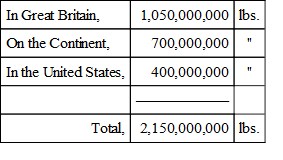

The second great measure of the Commission is to increase to five cents the tax on cotton, which has, since the close of our last financial year, begun to aid our revenue. The soil, climate, and seasons of our Southern States are peculiarly adapted to the culture of cotton. In India the fields are parched by the extreme heats of summer, and the staple shortened; in Algiers, the rains of autumn, which favor the young wheat, prevent the opening of the cotton-balls; but in the cotton States of the South, the moisture of the spring, the heats and showers of summer, and the dry weather and late frosts of autumn, all contribute to the full development of the cotton-plant; and the yield is twice or three times as great as in the cotton districts of the East. The staple, too, is much more valuable, and the yield and the quality of the staple are both improved by the application of guano. In 1859 the yield of the United States rose to 2,080,000,000 pounds, while the consumption of the civilized world was as follows:—

During the five years of war, the consumption was reduced more than one half by the deficiency; Great Britain was compelled to pay twice the usual amount for half the usual quantity, and cotton rose from ten cents to sixty cents in gold. The world was ransacked for cotton, and the whole addition made to the supply (chiefly from India and Egypt) did not exceed the increase of three years in the United States previous to the war. The Revenue Commission have made a very elaborate report upon this subject, and base their conclusions upon the advice and opinions of the chief manufacturers of New England, who concur in the opinion that the tax will be chiefly paid by the foreign consumer; that it will not give an undue stimulus to the culture of cotton abroad; that Japan and China have, since the decline of cotton to twenty pence in England, ceased to ship it, and are drawing upon Surat and Bombay; that Egypt, our chief rival, has nearly or quite reached her full capacity of production, while India makes little progress.

The late Confederacy, by imposing an export duty of twenty cents per pound, to be paid in gold; France, by her export duty on linen and cotton rags and skins of animals; Russia, by various export duties; Portugal, by her duties on wine exported; Great Britain, by her export duties, imposed in India, on gunny-cloth, linseed, jute, saltpetre, and opium; and Holland, by her monopoly and export duties on the coffee of Java,—give precedents for a tax on cotton. The United States are prohibited by the Constitution from levying an export duty, but may nevertheless impose an internal tax which will cling to the cotton both abroad and at home. A tax of five cents a pound will add but one cent to the cost of a yard of calico; and with a crop of 2,000,000,000 pounds, like that of 1859, will yield a revenue of $100,000,000, although the Commission do not anticipate more than half that revenue for a few years to come. It seems but reasonable that King Cotton, who made the war, should aid in defraying its expenses; and it is also just that England and France, his chief allies, should pay their tribute for the suppression of the revolt they did so much to encourage. The planters and free blacks of the South have sufficient incentives to the culture of cotton in the high prices it must bear for years to come; and the Commission have very wisely recommended a remission of the tax on all cotton cloth or yarn exported, which will give a stimulus to manufactures both at the South and the North, and enable our merchants to meet those of Great Britain in successful competition in all parts of the globe. The cotton tax, as a substitute for taxes on sales and manufactures, will meet the cordial support of our countrymen; and, if it oppose a slight check to production, they have already learned that half a crop gives more dollars than a whole one.

SPIRITS

Another change of great importance recommended by the Commission, both in their general Report, and in a special report devoted to this subject, is a reduction of the duty on spirits from two dollars to one dollar per gallon as a revenue measure, the higher duty having proved an utter failure. For some months past the average quantity that has monthly paid duty has been less than half a million gallons, or at the rate of six millions of gallons per year, while the entire annual product, by the census of 1860, exceeded ninety-two millions of gallons, and, at the customary rate of increase, would have amounted to one hundred and twenty millions of gallons, or ten millions a month, in place of half a million in 1866. It has been ascertained that in 1860 more than half the annual production was consumed in the arts. As alcohol it was used for ether, spirit-lamps, camphene, and burning-fluid; by apothecaries for tinctures and medicinal preparations; by hair-dressers for lotions; and it was also consumed in many manufactures. The duty has carried alcohol to five dollars per gallon, and nearly stopped its use in the arts, while it has not stopped the use of spirits as a beverage. It has drawn a revenue from the pockets of the people, and transferred it from the government to the illicit trader. While the duty ranged from twenty to sixty cents per gallon, the amount assessed was from six to seven million gallons per month; but the returns nearly ceased with the advance of duty two years since. Efforts have been made to sustain the present duty by reference to the practice of Great Britain, where a duty of $2.40 is imposed upon the imperial gallon; but the imperial gallon is more than twenty per cent larger than the wine gallon of America. The average prime cost of good spirits there being sixty cents a gallon, while it has been but twenty cents in the West, the percentage of the British duty is but 400 per cent, while the duty of the United States is 1000 per cent, or a rate 150 per cent above the rate abroad. Great Britain, in her compact territory, has employed 7,200 men in the preventive service, and 66 cruisers to check the evasions of her duties on spirits and tobacco; and it is estimated by good judges that a large part of the spirits, and more than half the tobacco, consumed in England escape the duty. Several thousand seizures are made annually, and it has been testified before Parliament that not one evasion in sixteen is detected. If this be so in Great Britain, it is not surprising that the government has failed, in this country, with its sparse population, to collect a duty of 1000 per cent, or that the experiment has cost the nation more than fifty millions. Such excessive duties may well be styled over-taxation, and tend to demoralize and corrupt our revenue officers, to encourage fraud, and to enrich illicit traders. The Commission believe that the reduction of the duty will restore alcohol to the arts, diminish fraud, and give us a revenue of at least $40,000,000 annually,—a sum nearly equal to the proceeds of the income tax.

INCOME TAX

The Revenue Commission clearly demonstrate by their Report and table of income, that this tax will not be required to meet our interest and current expenses, and they apparently retain a portion of it as a flank guard for their other items of revenue; but it is obvious from their very guarded Report that this flank guard may be dispensed with. The Commissioners very properly suggest that it is better to place this tax upon created wealth and net income than to levy it upon production, and in this all sensible men will concur; but we require at this time no surplus revenue of $81,000,000. Our revenue from foreign duties must exceed their estimate; and if it did not, a sinking fund of $32,000,000 is ample for a debt of $2,700,000,000, $400,000,000 of which draws no interest, and the residue of which we may well presume will soon be permanently funded at reduced interest. The income tax in Great Britain is but 1-2/3 per cent, and it is wise to reduce our own tax on the surplus incomes of the rich from ten to five per cent; but the suggestion that an income tax should be imposed on rents exceeding $300 is in conflict with the Commissioners' suggestion, at page 60 of their Report: "The general government has taken to itself nearly every source of revenue, except the single one of real estate, which had been before burdened with large expenditures for schools, roads, and other things with which the local governments stand charged," and "cases can be cited in which taxation upon real estate even now falls little short of confiscation. Justice and wise policy, therefore, would seem to demand that the national government should not now adopt any measures calculated to maintain or increase these burdens, but, on the contrary, do all in its power to diminish them."

Let the nation follow this judicious advice, and dispose of the additional charge on real estate by repealing the income tax, which we cease to require, or reducing it to a tax of three or four per cent upon dividends and coupons, which will yield at least ten millions. This will furnish a sufficient rear-guard for the corps which the Commission has marshalled.

To use another happy expression in the very able Report of the Commission,—"Freedom from multitudinous taxes, espionage, and vexations; freedom from needless official inquisitions and intrusions; freedom from the hourly provocations of each individual in the nation to concealments, evasions, and falsehoods; freedom for industry, circulation, and competition,—everywhere give the nation these conditions, and it will give in return a flowing income."

We indorse the conclusions of the Commission, but would carry them to their legitimate results,—the repeal of the inquisitorial tax on incomes.

One of the Commissioners, Mr. J. S. Hayes, in a special report upon the subject, proposes to draw some part of the revenue from the national bonds. Those which are now reached by the income tax when the holders are residents here should be reached hereafter by an impost on dividends and coupons, according to Mr. Hayes's idea. He urges that these bonds were issued when the currency was depreciated to 73 per cent, or 27 per cent below par; but it was the government paper that depreciated it, and the loyal men who subscribed for the national bonds in many instances used funds drawn from mortgages upon which they had advanced in gold the money they invested. Great Britain realized only 63 per cent or less in depreciated currency from her three-per-cents, but redeems them at par, or buys them in open market. There may be instances in which individuals evade local taxes by such investments, but even this tends to popularize the loans and reduce interest; and it may well be asked whether it would not be wiser for the nation to make the loan popular, treating it as sacred, and thus save twenty or thirty millions in interest annually by reducing interest one per cent, than to attempt to save two thirds that amount by taxes, which would inspire lenders with distrust, injure the credit of the nation, and weaken its resources in a future exigency.

TAXES ON GROSS RECEIPTS

The Commission, while they condemn charges on transportation, continue for the present nine millions in taxes on the gross receipts of steamers, ships, and railways, which it would be wise to relinquish at the earliest moment. The railways to earn one dollar must charge two, which doubles these taxes to the public, and adds to the cost of delivering each ton of coal and each bushel of grain at the seaports, so that our internal commerce now presents the strange anomaly of Indian corn selling at one dollar per bushel in Boston, and at thirty-six cents in Chicago, or less than the price in gold before the Insurrection. Such charges are an incubus on trade, and may wisely be abandoned.

PROVINCIAL COMMERCE

For the past ten years the Central and Eastern States have drawn large supplies of breadstuffs, animals, lumber, and other materials for our manufactures, from the Provinces; and under the Treaty of Reciprocity our fisheries have grown vastly in importance. The whole amount of this commerce, including the outfits and returns of the fishermen, is close upon $100,000,000, and the tonnage of arrivals and departures exceeds 7,000,000 tons. Under the Treaty we have imported Canadian and Morgan horses, oats for their support, barley of superior quality for our ale, lustre-wool for our alpacas, and boards and clapboards for our houses and for the fences and corn-cribs of our Western prairies. Indeed, the facilities for communicating with the Provinces are so great, that for some years past we have imported potatoes, coal, gypsum, and building stone to supply the wants of New York and New England. Is it wise, then, to cripple this growing trade by placing a duty of fifty per cent on the spruce and pine we require for the new houses whose construction the war has delayed, and by denying to Maine and Massachusetts the privilege of sending their pine down the Aroostook and St. John, as those who own townships on the waters of the Penobscot propose?

When Mr. Sumner moved the repeal of the Treaty, it was upon the ground that it prevented us from levying a tax on lumber. The Ministers of Canada have at once conceded this, and agree that internal duties may be levied on all they send to us, and thus meet in advance the position of Mr. Sumner. They have shown a desire to revive the Treaty, and to cherish the great commerce between contiguous states. Mr. Derby reports to the State Department that they will extend the free list, and include our manufactures; that they will discourage illicit trade, and repeal all discriminating tolls and duties. The position taken by the Ministers of Canada is eminently wise and judicious. While we may not concede all the privileges they ask, is it our policy to decline to negotiate,—to shut out the materials we require and can command at low rates? Is it wise to propose, as a committee of Congress has done, to reduce a free commerce of seven millions of tons to a traffic in plaster and millstones, and thus jeopard our fisheries and stimulate smuggling? The Canadian Ministers, who visited Washington on business connected with the Treaty, were kindly received by our Executive. They placed the Provinces on the true ground by their proffered concessions and offers to negotiate, and can stand at home upon the ground they took, while their course in retiring after the rebuff they received from the committee was dignified and judicious. When Congress has disposed of reconstruction, and found leisure to attend to revenue and finance; when it sees that we need new materials for our rising manufactures, and require access both by the east and the west to the exhaustless pine forests of Canada,7 to provincial oats and barley, purchasable at rates lower than those at which the West can afford to send them, and to coal on coasts which Nature designed for the supply of the gas-works and steamers of New England; when it finds proclamations issued excluding our fishermen from the waters to which the mackerel resort,—then Congress at last will doubtless be willing to resume negotiations, and to give to us coal, wood, butter, grain, fish, lumber, and horses at reasonable prices.

Eliminating from the summary of the Commission the items which are condemned by their Report, we have the following result:—

REVENUE LIST OF COMMISSIONERS, EXCLUDING TAXES ON INCOME AND TRANSPORTATION

We thus deduce from the estimate of the Secretary and the conclusions to which we are led by the Commission a surplus revenue or sinking fund of $44,000,000, and this, too, after discontinuing all taxes on production, income, and transportation, and liberating industry from the trammels imposed by war. In addition, we may expect from cotton, whenever the crop exceeds two millions of bales, a further revenue from the five-cent tax, while the income from customs, which we rate at $130,000,000, has actually been increased since June, 1865, to the amount of $58,000,000 more.

These results, achieved by the country while emerging from the smoke of the battle-field, and disbanding its troops and placing army and navy on a peace footing, are in the highest degree reassuring. What is there, then, to prevent the nation's prompt return to specie?