Полная версия

Полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 17, No. 102, April, 1866

But instead of going to a Walden and camping on the shady edges of the world, to see what could be done without civilization, I preferred to camp down in the heart of civilization, and see what could be done with it;—not to fly the world, but to face it, and give it a new emphasis, if so it should be; to conjure it a little, and strike out new combinations of good cheer and good fellowship. In fact, it seems to me ever that the wild heart of romance and adventure abides no more with rough, uncouth nature than with humanity and art. To sit under the pines and watch the squirrels run, or down in the bush-tangles of the Penobscot and see the Indians row, is to me no more than when Gottschalk wheels his piano out upon the broad, lone piazza of his house on the crater's edge, and rolls forth music to the mountains and stars. Here too are mystery, poesy, and a perpetual horizon.

This for romance; but true adventure abides most where most the forces of humanity are. So I camped down in the heart of things, surely; for in the next room were a child, kitten, and canary; in the basement was a sewing-machine; while across the entry were a piano, flute, and music-box. But Providence, that ever takes care of its own, did ever prevent all these from performing at once, or the grand seraglio of Satan would have been nothing to it.

But if in getting a room one is haunted by the two gentlemen, in getting furniture and provisions one is afterward haunted by the "family" relation. It is a result of the youthfulness of our civilization, that as yet it is cumbrous and unwieldy. We do not yet master it, but are mastered by it; and nowhere in America will one find the charming arrangements for single living which have filled the Old World with delightful haunts for the students of every land. As yet we provide for people, not persons; and the needs of the single woman are no more considered in business than in boarding. Forever she is reminded of the Scripture, "He setteth the solitary in families"; and forever it seems that all must be set there but herself. For nice crockery is sold by the set, knives and forks by the half-dozen, the best coal by the half-ton; the tin-pans are immense, and suggest a family Thanksgiving; pokers gigantic, fit only to be wielded by the father of a family; and at market the game is found with feet tied together in clever family bunches, while one is equally troubled to get a chop or a steak, because it will spoil the family roast,—and as to a bit of venison for breakfast, it may be had by taking two haunches and a saddle. In desperation she exclaims with O'Grady of Arrah na Pogue, "O father Adam, why had you not died with all your ribs left in your body!" For since there is neither place nor provision for her in the world, why indeed should she have come?

Having once, on a fruitless tour through Faneuil Hall Market for a single slice of beef, come to the last stall, and here finding nothing less than a sirloin of six pounds, which was not to be cut, I could only answer imploringly, "But pray, what is one person to do with a sirloin of six pounds?" A relenting smile swept over the stern butcher's face. "I will cut it!" he said, brandishing the knife at once. "Thank you," I cried, with a gush of emotion; for he seemed a really religious man. He comprehended that there was at least one solitary whom the Lord had not set in a family. I took the number of his stall.

Nor is it yet too late to be grateful to him who proposed breaking a bundle of cutlery in my behalf. He too realized the situation, and saw that by no possibility could one person gracefully get on with six knives and forks at once.

Indeed, since one's single wants are not regularly met by this system of things, the only way at present to get them answered is by favor. So that the first item in setting up an establishment is not only to bring one's resources about one, but to find the people of the trade who will assist in the gladdest way. One wants the right stripe in the morning and evening papers, but none the less happy are just the right merchant and just the right menial. Since all of life may be rounded into rhythm, shall we not even consult the harmonies in a grocer or an upholsterer? Personal power can be carried into every department. It is well to find where one's word has weight, then always say the word there. This is a part of the quest which makes life a perpetual adventure; and there is nothing more piquant than to go on an exploring tour for one's affinities among the trades. It is perhaps rather more of the sensational than the sentimental, and might be marked in the private note-book with famous headings, like those of the New York papers on a balloon marriage, as, The last affinity item! A raid among the magnetisms! or, Hifalutin among prunes! However, in some subtile way, one soon divines on entering a store whether she is to be well served there, and must follow with tact the undercurrent in the shop as well as in the salon. If it be not the right encounter, ask for something there is not, and pass on to the next. Thus, "my grocer" apologizes for keeping honey, because I do not eat sweets, and proposes to open the butter trade because it is so annoying to go about for butter; "my stoveman" descends from the stilts of the firm, looking after these chimney affairs himself; "my carpenter" says, "Shure, an' ye don't owe me onything; I'd work for ye grat-tis if I could"; "my cabinet-dealer" sends tables and wardrobes at midnight if desired, and takes them back and sells them over the next day; even the washerwoman is an affinity, exclaiming, "Shure, an' ye naid n't think I'll be chargin' ye with all the collars an' ruffles ye put in,—shure, an' I'll not."

Perhaps it sounds a little egotistic to say "my grocer," &c., but is not this the way that heads of families talk, and am I not head and family too? At least the solitary may soothe themselves with the family sounds. Indeed, it soon appears that all these faithful servers are like to become so radical a part of the my and mine of existence, as to make it really alarming. When one's comfort is thus bound up in fire-boy and washerwoman, alas! what will become of the grand philosophy of Epictetus?

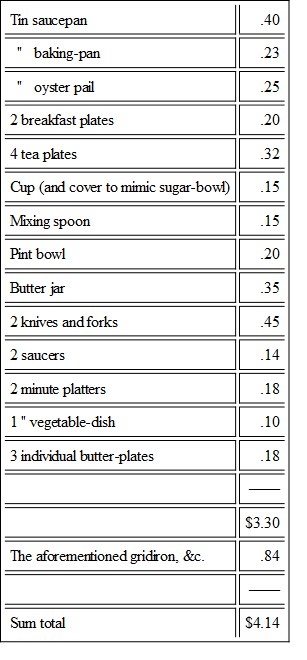

To begin housekeeping proper, one will need at least a bread-knife and tumbler, a gridiron and individual salt,—cost eighty-four cents. My list also includes for kitchen and table use:—

To this should be added a small iron frying-pan for gravied meats. The quart pail usually did duty for vegetables, the saucepan for soup, while prime chops and steaks appeared from the gridiron. Tea-spoons are not included, nor any tea things whatever. These excepted, it will be seen that less than five dollars gives a full housekeeping apparatus, with pretty white crockery enough to invite a dinner guest.

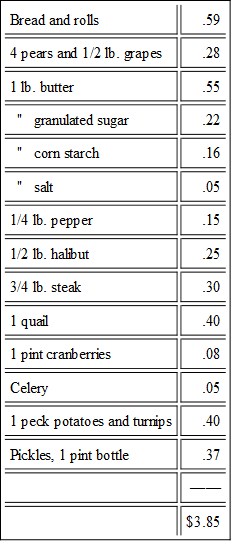

The provisions for one week were:—

At the end of the week there was stock unused to the amount of $1.00, making $2.85 for actual board, (I did not dine out once,) and this included the most expensive meats, which one might not always care to get; for it is not parsimony that often prefers a sirloin steak at thirty cents to a tenderloin at forty cents. But this note may be added. Don't buy quails, they are all gizzard and feathers; and don't buy halibut, till you have inquired the price. It will also be perceived that beverages are not mentioned. None of that seven million pounds of tea shipped from China last September ever came to my shores. If this article were added, there would come in large complications of furniture and food, beside the obligation of being on the stairs at early hours in fearful dishabille, watching for the milkman, as I have seen my sister-lodgers.

The pecuniary result is, that, for less than three dollars per week and the work, one may have the best food in the market; for three dollars and no work, one may have the very worst in the world.

For any ordinary amount of cooking, an open grate is admirable, though it do not furnish that convenient stove-pipe whereon lady boarders can smooth out their ribbons, &c.; but it is accessible, and draws the culinary odors speedily out of the room. At least it is admirable from fall to the middle of December, when you find that it draws the heat, as well as the odors, up chimney; then you will get a "Fairy" stove of the smallest size, with a portable oven, and fairly go into winter quarters. But by the grate one may boil, broil, and toast, if not roast; for I used with delight to cook apples on the cool corners, giving them a turn between sentences as I read or wrote. They seemed to have a higher flavor, being seasoned with thoughts; but it was not equally sure if the thoughts were better for being seasoned with apple. However, one must not count herself so recherché as Schiller, who could only write when his desk was full of rotten apples.

Still the grate has no oven, and the chief difficulty is in bread. One starts bravely on the baker's article, but such is the excess of yeast that the bitterness becomes intolerable. Then one begins to perambulate the city, and thinks she has a prize in this or that brand,—is enamored of Brigham's Graham biscuits, hot twice a week, or of Parker's rolls,—but soon eats through novelty to the core, and that is always hops. Thus one goes from baker to baker, but it is only a hopping from hops to hops. I see with malicious joy that the exportation tariff is to be removed from hops.

As to crackers, they are of course no more available than pine splints, though the Graham variety is the best. Aerated bread is probably the most healthful, but this is pitiable to live on; it tastes like salted flannel.

Finally, let me confess to the use of a friendly oven near by, and from this came every week the indispensable Graham cakes, which are the despair of all the cooks. Of course, on this point it is impossible, without seeing their experiment, to say why it failed; but all the given conditions being met, if the cakes were tough, there was probably too much meal; if soggy, too little. Also the latest improvement is not to cut them in diamonds, but to roll them into various forms. After scalding, the dough is just too soft to be handled easily; it is then to be dropped into meal upon the board, separating it in small quantities with a spoon or knife, and rolling lightly in the meal into small biscuits, rolls, or any form desired. But do not work in any of the meal. Possibly some of the failures come from disregard of this; for the meal which is added after, being unscalded, is not light, and would only clog the cakes. And, in eating, the biscuits should be broken, never sliced. They are in their prime when hot, quite as much as Ward Beecher's famous apple-pie; but, unlike that, may be freshened afterward by dipping in cold water and heating in a quick oven just before wanted. In other words, they may be regenerated by immersion.

As to the system of this minute household,—if any should be curious to know,—it was to have breakfast-dishes despatched, with the dinner vegetables pared, at half past nine, a. m.; dinner out of hand by two, p. m.; bread and butter and Cochituate precisely at six, p. m.

In one of Mr. and Mrs. Hall's "Memories of Authors," mention is made of a little Miss Spence, who, with rather limited arrangements in two rooms, used to give literary tea-parties, and was shrewdly suspected of keeping her butter in a wash-bowl. I did not follow any such underhanded proceeding. I kept my butter on the balcony. All-out-doors was my refrigerator; and if one will look abroad some cool, glittering night, he may yet see my oyster-pail hung by a star, or swinging on the horns of a new moon.

Perhaps it is fair to mention, however, that on one glittering night the mercury fell below zero, and the windows all froze hard down, and there was the butter locked on the outer side! And oh! it is such a trying calamity to be frozen in from one's butter! But after this experience the housekeeper shrewdly watches for these episodes of weather, and takes the jar in of a night. So it is that eternal vigilance is the price even of butter.

Still it seemed that, with careful and economizing mind, on six feet by thirteen it was not only possible to live, but to take table-boarders. Certainly nothing could be gayer, unless to ramble delightfully forever in one of those orange-colored ambrotype-saloons, drawn by milk-white oxen; or to quarter like Gavroche of Les Miserables among the ribs of the plaster elephant in the Bastile; or more pensively to abide in the crannied boat-cabin of the Peggotys, watching the tide sweep out and in.

This must be the weird, barbaric side of the before-named brick and mortar flat of five rooms.

Pope, the tragedian, said that he knew of but one crime a man could commit,—peppering a rump steak. It is an argument for boarding one's self that all these comfortable crimes thus become feasible. One may even butter her bread on three sides with impunity; or eat tamarinds at every meal, running the risk of her own grimaces; or take her stewed cherries with curious, undivided interest as to whether a sweet or sour one will come next (dried cherries are a great consolation); and, being allowed to help herself, can the better bring all the edibles to an end at once upon her plate,—an indication of Providence that the proper feast is finished. Wonderfully independent all this! Life with the genuine bachelor flavor. As L. remarked, even the small broom in the corner had a sturdy little way of standing alone.

Perhaps there is nothing finer than the throng of fancies that comes in a solitary breakfast. Then one reaches hands of greeting to all the lone artists taking their morning acquavite in Rome; to the young students of Germany at their early coffee and eggs; even remembering the lively grisette of Paris, as, with a parting fillip to her canary, she flits forth from her upper room; and finally drinks to the memory of our own Irving at his bachelor breakfast among the fountains and flowers in the Court of Lions at the Alhambra.

And very sweet, too, it is, in the fall of the day, to sit by the rich, ruby coals, and think of those who are far, until they come near; and of that which is hoped for, until it seems that which is; to sit and dream, till

"The breath of the great Lord God divineStirs the little red rose of a room."This it is to keep house with a bread-knife and tumbler, a gridiron and an individual salt. This it is to vitally understand the multum in parvo of existence. This it is to have used and mastered civilization.

But the total pecuniary result is, that the rent of the very smallest room in central location—at the hub of the hub—will not be less than three dollars per week, without light, heat, or furniture. Fire, and a boy to make it, will be two dollars per week; light seventy-five cents if gas, twenty-five cents if kerosene; this, with board at three dollars, washing at one dollar per dozen, and the constant Tribune, etc., brings one up to the pretty little sum of ten dollars per week, without a single item of luxury, unless daily papers can be called luxurious. Or, should one go out to breakfasts and dinners, nothing tolerable can be had under five dollars per week; and this gives a total of twelve dollars. Then, to complete one's life, there must be clothing, literature, perhaps travel and hospitality, making nearly as much more; and to crown it, there must be the single woman's favorite lecturer or prima donna; for ah! we too, in some form, must have our cigars and champagne. A round thousand a year for ever so small a package of humanity!

And of course, as goods are higher in small quantities, so in living by this individual way it will be discovered that prices are prodigious, but that weights and measures are not. After opening the small purse regularly at half-hour intervals for several weeks, one at length finds herself opening it when there is nothing to be bought, from mere muscular habit. Altogether it is easy to spend as much as a second-rate Congressman, without any of his accommodations. This is wherein one does not master civilization.

Mr. McCulloch, in his Report on the Treasury, suggested an increase of salary for certain subordinates in his department, declaring that they could not support their families in due rank on four, five, or even six thousand dollars a year. It is easy to believe it. It is easy to believe anything that may be stated with regard to money, except that one will ever be able to get enough of it to cover these terrible charges. The entire fabric of things rests on money; and our prices would drive a respectable Frenchman into suicide. O poor Robin Ruff! alas for your grand visions that you sang so glowingly to dear Gaffer Green! In this age of the world, O what could you do, or where could you go, e'en on a thousand pounds a year, poor Robin Ruff?

And so long as each must keep her separate establishment, it will not be found possible to reduce living much below the present figures. But London has more wisely met the pressure of the times in those magnificent clubhouses, which have made Pall Mall almost a solid square of palaces hardly inferior to the homes of the nobility themselves. Each of these houses has its hundreds of members, who really fare sumptuously, having all the luxuries of wealth on the prices that one pays here for poverty. The food is furnished by the best purveyors, and charged to the consumers at cost; all other expenses of the establishment being met by the members' initiation fees, ranging from £32 entrance fee and £11 annual subscription, to £9 and £6 for entrance and subscription. Being admirably officered and planned throughout, these gigantic households are systematized to the beautiful smoothness of small ones; their phrase of "fare-well" is one of epicurean invitation, not of dismissal; while such are the combined luxuriousness and economy that, says one authority, "the modern London club is a realization of a Utopian cœnobium,—a sort of lay convent, rivalling the celebrated Abbey of Thelemé, with the agreeable motto of Fais ce que voudras, instead of monastic discipline."

Of course, New York also has followed suit, and there, too, clubs are trumps; but, according to "The Nation," with this remarkable exception, that "at these houses the leading idea seems to be, not to furnish the members at cost price, but to increase the finances with a view to some future expenditure." The writer reasonably observes, that "what a man wants is his breakfast or dinner cheaper than he can get it at the hotel, and not to pay thirty or sixty dollars annually in order that ten years hence the club may have a new building farther up town." And Boston has followed New York, with its trio of well-known clubs, differing also from those of London in having poorer appointments and the highest conceivable charges.

But most of these clubs do not include lodgings, and none of them include ladies. It remains for America to give us the club complete in both. There is every reason why women should secure elegant and economical homes in this way. Indeed, in the present state of things, there seems no other way to secure them. There is no remedy but in a system of judicious clubbing. Since this phase of the world seems made up for the family relation, then ladies must make themselves into a sort of family to face it. Where is the coming man who shall communicate this art of clubbing, which has not yet even been admitted into the feminine dialect? Mr. Mercer is doing for the women who wish to go out in the world that which womanly gratitude can but lightly repay.6 Where is the kindly, honest-hearted Mr. Mercer who shall further a like enterprise here,—a provision of quarters for those who can pay reasonably and who do not wish to go away? This would be a genuine Stay-at-home Club, a Can't-get-away Club of the very happiest sort. And this alone can put life in our noble cities, where active-brained women love to be, on something like possible terms.

In Miss Howitt's "Art Student at Munich,"—a charming sketch, by the way, of women living en bachelier abroad,—we find one young enthusiast idealizing upon this very need of feminine life, which she christens an Associated Home. In her artistic mind it takes the form of an outer and inner sisterhood,—the inner devoted to culture, the outer attending to the useful, ready alike to broil a steak or toe a stocking for the more ethereal ones of the household. This is all quite amiably intended, but no queen-bee and common-bee scheme of the sort seems to be either generous or practicable. It involves at once too much caste and too much contact. We do not wish to find servants or scrubs in our sisters, nor do we wish at all times even to see our sisters. There must be elbow-room for mood and temperament, as well as high walls of defence. The social element is too shy and elusive, and will not, like a monkey, perform on demand; therefore our plan abjures all these poetic organizations, which have a great deal of cant and very little good companionship; it has no sentimentalism to offer, proposing an association of purses rather than of persons,—a household on the base of protection rather than of society,—a mere combining for privileges and against prices. It is resolved into a simple matter of business; and the only help women need is that of an organizing brain to put themselves into this associate form, whereby they can meet the existing state of things with somewhat of human comfort.

Are we never to obtain even this, until the golden doors of the Millennium swing open? Ah, then indeed one must melt a little, looking regretfully back to Brook Farm, undismayed by the fearful Zenobia; looking leniently toward Wallingford, Lebanon, and Haryard. Anything for wholesome diet, free life, and a quiet refuge.

But whether to live alone or together, the first want is of houses,—which is another hitch in the social system. In the city a building-lot is an incipient fortune; and the large sum paid for it is the beginning of reasons for the large rent of the building that is put upon it. But then if ground is costly, air is cheap,—land is high, but sky is low; and one need have but very little earth to a great deal of house. A writer, describing the London of thirty years ago, speaks of the huge, narrow dwellings, full five stories high, and says that the agility with which the inmates "ran up and down, and perched on the different stories, gave the idea of a cage with its birds and sticks"; and the like figure seems to have occurred to the queer Mademoiselle Marchand of "Denise," who, as she toiled to her eyrie on the topmost landing, exclaimed, "One would think these houses were built by a winged race, who only used stairs when they were moulting!" But these same lofty houses are the very thing we must have to-day, all but the running up and down. Build us houses up, and up, as high as they will stand; give us plenty of sky-parlors, but also plenty of steam-elevators to go to and from "my lady's chamber." It is not a wise economy to devote one's precious power to this enormous amount of stair-work. It is not a kind of exercise that is sanitive. The Evans House and Hotel Pelham, for instance, are very pretty Bostonianisms, but all their rooms within range of ordinary means are beyond the range of ordinary strength. The achievement of twenty flights a day, back and forth, would leave but small surplus of vigor. While the steam power is there for heating purposes, why not use some of it to propel the passengers up and down that wilderness of rosy boudoirs? Is there any reason why this labor-saving machine, the steam-elevator, which we now associate with Fifth Avenue luxury, should not be the common possession of all our large tenanted buildings? And is there any reason, indeed, in our houses being no better appointed than the English houses of thirty years ago? Ruskin has been honorably named for renting a few cottages with an eye to his tenants as well as himself; but the men who in our crowded cities shall erect these mammoth rental establishments, with steam access to every story, will build their own best monuments for posterity. We commend it to capitalists as a chance to invest in a generous fame. Until this is done, we shall even disapprove of bestowing any more mansions upon our beloved General Grant. It is not gallant. Until then, too, how shall one ever pass that venerable Park Street Church of Boston, without the irreverent sigh of "What capital lodgings it would make!" Those three little windows in the curve, looking up and down the street, and into the ever-fascinating Atlantic establishment; the lucky tower, into which one might retreat, pen in hand, if not wishing to be at home to callers nor abroad to himself,—Carlyle-like, making the library at the top of the house; and all within glance of the dominating State-House, whither one might steal up for an occasional lunch of oratory or a digest of laws. We also hear of a new hotel being builded on Tremont Street, and wonder if there will be any rooms fit for ladies, and whether one of those in the loft will rent for as much as a charming villa should command.