Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 14, No. 83, September, 1864

"At any rate, I will add my contribution to this altar of an unknown God. Besides, there are some blackberries that I must have," exclaimed Optima, releasing her active limbs from the carriage in a very summary fashion.

Tossing a little stick upon the rock, she hastened to gather the abundant fruit, a little for herself, a good deal for Madame and Miselle, until Gypsy and Fanny stamped and neighed with impatience, and Monsieur cried cheerily,—

"Come, young woman, come! We are not half-way to Sandwich, and the horses will be devoured by these flies as surely as Bishop Hatto was by mice."

And so on through miles of merry woodland, by fields and orchards, whose every crop is a fresh conquest of man over Nature in this one of her most niggardly phases, by desolate cabins and lonely farms, until at a sudden turn the broad, beautiful sea swept up to glorify the scene. And while Miselle with flushed cheeks and tearful eyes drank in the ever-new delight of its presence, Monsieur began a story of how a man, almost a stranger to him, had come one winter evening and begged him for God's love to go and help him search for the body of his brother, reported by a wandering madwoman to be lying on this beach, and how he begged so piteously that the listener could not choose but go.

And as Monsieur vividly pictured that long, lonely drive through the midnight woods, the desolate monotony of the beach, along whose margin curled the foam-wreaths of the rising tide, while beyond phosphorescent lights played over a world of weltering black waters,—as he told how, after hours of patient search, they found the poor sodden corpse and tenderly cared for it,—as Monsieur quietly told his tale and never knew that he was a hero, Miselle turned shuddering from sea and beach and the mocking play of the crested waves, as they leaped in the sunshine and then sank back to sport hideously with other corpses hidden beneath their smiling surface.

Presently the sea was again shut off by woodland, and the scattered houses closed into a village, nay, a town, the town of Sandwich; and swinging through it at an easy rate, the carriage halted before an odd-looking building, consisting of a quaint old inn, porched and gambrel-roofed, joined in most unholy union to a big, square, staring box, of true Yankee architecture.

Descending with reluctance, even after three hours of immobility, from her breezy seat, Miselle followed Madame into the quiet house, whose landlord, like many another man, makes moan for "the good old times" when summer tourists and commercial travellers filled his rooms and the long dining-table, now unoccupied, save by our travellers and two young men connected with the glass-manufactories.

Rest, plenty of cool water, and dinner having restored the energies of the travellers, it was proposed that they should proceed at once to the Glass Works. And now, indeed, did Fortune smile upon this band of adventurous spirits; for when the question of a guide arose, mine host of the inn announced himself not only willing to act in that capacity, but eminently qualified therefor by long experience as an operative in various departments of the works.

"How fortunate that the stage-coaches and peddlers no longer frequent Sandwich! If our friend had them to attend to, he could not devote himself to us in this charming manner," suggested Optima, as she and Miselle gayly followed Monsieur, Madame, and Cicerone down the long sunny street, whose loungers turned a glance of lazy wonder upon the strangers.

Passing presently a monotonous row of lodging-houses for the workmen, and a public square with a fountain, which, as Optima suggested, might be made very pretty with the addition of some water, the travellers approached a large brick building, many-windowed, many-chimneyed, and offering ingress through a low-browed arch of so gloomy an aspect that one looked at its key-stone half expecting to read there the well-known Dantean legend,—

"Lasciate ogni speranza, voi chi'ntrate!"Nor was the illusion quite destroyed by handling, for through the arch and a short passage one entered a large, domed apartment, brick-floored and dimly lighted, whose atmosphere was the breath of a dozen flashing furnaces, whose occupants were grimy gnomes wildly sporting with strange shapes of molten metal.

"This is the glass-room, and in these furnaces the glass is melted; but perhaps you will go first and see how it is mixed, and how the pots are made to boil it in."

"Yes, let us begin at the beginning," said all, and were led from the Inferno across a cool, green yard, into a building specially devoted to the pots. In a great bin lay masses of soft brown clay in its crude condition, and upon the floor were heaped fragments of broken pots, calcined by use in the furnaces, and now waiting to be ground up into a fine powder between the wheels of a powerful mill working steadily in one corner of the building. In another, a row of boxes or pens were partially filled with a powdered mixture of the raw and burnt clay, and this, being moistened with water, was worked to a proper consistency beneath the bare feet of several stout men.

"This work, like the treading of the wine-press, can be properly performed only by human feet," remarked Monsieur.

"So when next we sip nectar from one of your straw-stemmed glasses, we will remember these gentlemen and their brothers of the wine-countries, and gratefully acknowledge that without their exertions we could have had neither wine nor goblet," said Miselle, maliciously.

"No," suggested Optima, "we will enjoy the result and forget the process. But what is that man about?"

"Making sausages out of cheese, I should say," replied Monsieur; and the comparison was almost unavoidable; for upon a coarse table lay masses of moulded clay, in form and size exactly like cheeses, from which the workman separated with a wooden knife a small portion to be rolled beneath his hand into cylindrical shapes some four inches in length by two in diameter.

These a lad carefully placed upon a long and narrow board to carry up to the pot-room, whither he was followed by the whole party.

Miselle's first impression, upon entering this great chamber, was, that she was following a drove of elephants; but as she skirted the regular ranks of the great dun monsters and came to the front, she concluded that she had stumbled upon the factory of Ali Baba's oil-jars. At any rate, the old picture in the "Arabian Nights" represented Morgiana in the act of pouring the boiling oil into vessels marvellously like these, and in each of these was room for at least four robbers of true melodramatic stature.

Among these jars, with the noiseless solicitude of a mother in her sleeping nursery, wandered their author and guardian, a pale, keen man, and so rare an enthusiast in his art that one listening to him could hardly fail to believe that the highest degree of thought, skill, and experience might worthily be expended upon the construction of these seething-pots for molten glass.

"Will you look at this one? It is my last," said he, tenderly removing a damp cloth from the surface of something like the half of a hogshead made in clay.

"I have not begun to dome it in yet; it must dry another day first," said the artist, passing his hand lovingly along the smooth surface of his work.

"Then you cannot go on with them at once?" asked Madame.

"Oh, no, Ma'am! They must dry and harden between the spells of work upon them, or they never would stand their own weight. This one, you see, is twelve inches thick in the bottom, and the sides are five inches thick at the base, and graduated to four where the curve begins. Now if I was to go right ahead, and put the roof on this mass of wet clay, I shouldn't get it done before the whole would crush in together. I have had them do so, Ma'am, when I was younger, but I know better now. I sha'n't have that to suffer again."

"And what are you at work upon while this dries?"

"Here. This one is just begun. Shall I show you how I do it? John, where are those rolls? Yes, I see. Now, Ma'am, this is the way."

Taking one of the rolls in his left hand, and manipulating it with his right, our artist laid it upon the top of the unfinished wall, and with his supple fingers began to dovetail and compact it into the mass, pressing and smoothing the whole carefully as he went on.

"You see I must be very careful not to leave any air-bubbles in my work; if I do, there will be a crack."

"When the pot dries?" asked Madame.

"No, Ma'am, when it is heated. I suppose the air expands and forces its way out," said the man, shyly, as if he were more in the habit of thinking philosophy than of talking it. "But see how smooth and fine this clay is," added he, enthusiastically, passing his finger through one of the rolls. "It is as close-grained and delicate as—as a lady's cheek."

"But, really, how could one describe the shape of these creatures?" asked Optima aside of Miselle, as she stood contemplating a completed monster.

"By comparing them to an Esquimaux lodge, with one little arched window just at the spring of the dome. Doesn't that give it?"

"Perhaps. I never saw an Esquimaux lodge; did you, my dear?"

"No, nor anything else in the least degree resembling these, unless it was the picture of the oil-jars. Choose, my Optima, between the two."

"Hark! we are losing something worth hearing."

So the young women opened their ears, and heard the pallid enthusiast tell how, after days and weeks of labor, and months of seasoning, the pots were laboriously carried to a kiln, where they were slowly brought to a red heat, and then suffered to cool as slowly. How the pot was then taken to one of the furnaces of the Inferno, and a portion of its side removed to receive it; how it was then built in, and reheated before the glass-material was thrown in; and how, after all this care and toil, it was perhaps not a week before it cracked or gave way at some point, and must be taken away to make room for another. But this was unusually "hard luck," and the pots sometimes held good as long as three months.

"And what becomes of the old ones?" asked Optima, sympathetically.

"Oh, they are all used over again, Miss. There must be a proportion of burnt clay mixed with the raw, or it would be too rich to harden."

"And what is the proportion?"

"About one-third of the cooked clay, and two-thirds of the raw."

"And where does the clay come from?"

"Nearly all from Sturbridge, in England. Some has been brought from Gay Head, on Martha's Vineyard; but it doesn't answer like the imported."

Leaving the courteous artist in glass-pots to his labors, the party, crossing again the breezy yard, entered a dismal brick-paved basement-room, where grim bakers were attending upon a number of huge ovens. One of these was just being filled; but instead of white and brown loaves, golden cake, or flaky pies, the two attendants were piling in short, thick bars of lead, and, hurry as they might, before they could put in the last of the appointed number, little shining streams of molten metal began to ooze from beneath the first, and trickle languidly toward the mouth of the oven.

But our bakers were ready for them. With hasty movement they threw in a quantity of moistened clay, shaping and compacting it with their shovels as they went on, until in a very few moments they had completed a neat little semi-circular dike just within the door, as effectual a barrier to the glowing pool behind it, wherein the softened bars were rapidly disappearing, as was ever the Dutchman's dike to the ocean, with whom he disputes the sovereignty of Holland.

A wooden door was now put up, and the baking was left to itself for about twenty-four hours, at the end of which time the lead would have become transformed into a yellowish powder, known as massicot.

"You will see it here. They are just beginning to clear this oven," said Cicerone, pointing to a row of large iron vessels which the workmen were filling with the contents of the just opened kiln.

"And what next? What is it to the glass?" asked Miselle, unblushing at her ignorance.

"Next, it is put into these other kilns, and kept in motion with the long rakes that you see here, and at the end of forty-eight hours it will have absorbed sufficient oxygen from the atmosphere to turn it from massicot to minium, or red-lead. Look at this, if you please."

Cicerone here pointed to other iron vessels, in shape like the bowl out of which the giant Blunderbore ate his bread and milk, while trembling little Jack peeped at him from the oven; but these bowls were filled with a beautiful scarlet powder of fine consistency.

"That is red-lead, one of the most important ingredients in fine flint-glass, as it gives it brilliancy and ductility. But it is not used in the coarser glasses. And here is the sand-room."

So saying, Cicerone led the way to a light and cheerful room of delicious temperature, even on that summer's day, where, upon a low, broad, iron table, heated from beneath by steam-pipes, lay a mass of what might indeed be sand, and yet differed as much from ordinary sand as a just washed pet-lamb differs from an old weather-beaten sheep.

Like the lamb, the sand had been washed with care and much water, and now lay reposing after its bath at lazy length, enjoying its kief, like a sworn Mussulman. This sand is principally brought from the banks of Hudson River and the coast of New Jersey; but a finer article of quartz sand is found in Lanesboro', Massachusetts.

In the centre of the room stood a great sifting-machine, worked by steam; and the sand, after being thoroughly dried, was passed through this, coming out a fine, glittering mass, very much resembling granulated sugar, so far as looks are concerned.

"Now it is ready to be sent up to the mixing-room; but if you will step on this drop, we will go up before it," said the civil workman here in charge.

So some of the party stepped upon a solid platform about six feet square, lying under a trap in the floor overhead, and were slowly wound up to the mixing-room, feeling quite sure, when they stepped upon the solid floor once more, that they had done a very heroic thing, and were not hereafter to be dismayed by travellers' tales of descents into coal-mines, or swinging to the tops of dizzy spires in creaking baskets.

Here, in the mixing-room, stood great boxes, filled with sand, with red-lead, or with sparkling soda and potash; and beside a trough stood, shovel in hand, a good-natured-looking man, who was busily mixing portions of these three ingredients into one mass.

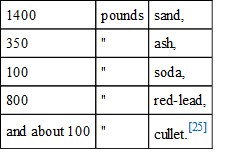

Him Miselle assailed with questions, and learned that the trough contained

[25] "Cullet" is the waste of the glass-room. The superfluous material taken up on the pontil, and the shards of articles broken in process of manufacture. The ingenious reader will thus interpret the heading of this paper.

This was to be a fine quality of flint-glass, and to it might be added coloring-matter of any desired tint; but in the choice and proportion of this lay one of the principal secrets of the art.

All this information did the civil compounder vouchsafe to Miselle, with the indulgent air of one who humors a child by answering his questions, although quite sure that the subject is far above his comprehension; and he smiled in much amusement at seeing his answers jotted down upon her tablets. So Miselle thanked him, smiling a little in her turn, and they parted in mutual satisfaction.

"These trucks you see are ready-loaded with the frit, or glass-material, and are to be wheeled down to the furnaces presently," said Cicerone. "But, before following them, we had better go down and see the fires."

Descending a short flight of stone steps, the party now entered a long, dark passage, through which a torrent of wind swept, driving before it the ashes and glowing cinders that dropped continually from a circular grating overhead. The ground beneath was strewn with fire, and the whole arrangement offered a rare opportunity to any misanthrope whose preferences might point to death in the shape of a fiery shower-bath.

In a gloomy crypt, opening near the grating, stood a gnome whose duty it was to feed the furnace overhead with soft coal, which must be thrown in at a small door and then pushed up and forward until it lay upon the grating where it was consumed. Around this central fire the glass-pots, ten to each furnace, are arranged, their lower surfaces in actual contact with it, while the domed roof reverberates the heat upon them from above.

All around stood sturdy piers of brick and iron, and low-browed arches, crushed, one could not but fancy, out of their original proportions by the immense weight they were forced to uphold.

Returning to the Inferno, Cicerone led the way to a pot which was being filled with frit from one of the little covered cars that he had pointed out in the mixing-room. This process was to be effected gradually, as he explained,—a certain portion being at first placed in the heated pot, and suffered to melt, and then another, until the pot should be full, when the door of it would be put up and closed with cement.

"And how long before the frit will be entirely melted?" asked Monsieur.

"From thirty-six to sixty hours. The time varies a good deal with the seasons, and different sorts of glass take different times to melt. This flint-glass melts the easiest, and common bottle-glass takes the longest. Crown-glass, such as is used for window-panes, comes between the two; but that is not made here."

"And when the glass is sufficiently boiled, what next?"

"You shall see, for here is a pot just opened, and this man with the long iron rod, called a pontil, or punty, in his hand, is about to skim it."

"What is there to skim off?"

"Oh, there will be impurities, of course, however carefully the ingredients are prepared. Some of these sink to the bottom, and some rise in scum, or, as it is called here, glass-gall, and sometimes sandiver."

"Just like broth or society, isn't it, Optima?" suggested Miselle, aside.

"Why don't you discover a social pontil, then?"

"Oh, I have no taste for reforming. What would there be to laugh at in the world, if the human sandiver were removed?"

"It might be an improvement to have the gall removed, my dear," remarked Optima, significantly; but Miselle was too busy in watching the skimming to understand the gentle rebuke.

Thrusting the pontil far into the pot, the workman moved it gently from side to side, turning it at the same time, until he suddenly withdrew upon its point a large lump of glowing substance, which he shook off upon a smooth iron table standing near, called a marver, (that is, marbre,) in size and shape not unlike the largest of a nest of teapoys. Here the lump of sandiver lay, while through its mass shot rays of vivid prismatic color, glowing and dying along its surface so vivaciously that one needs must fancy the salamander no fable, and that this death of gorgeous agony was something more than the mere cooling of an inert mass of matter.

"You see how bubbly and streaked that is now?" broke in the voice of Cicerone upon Miselle's little dream. "But after standing awhile the air will all escape from the pot, leaving the glass smoother, thicker, and tougher than it is now. Don't you want to look in, before it cools off?"

With a mental protest against the fate of those luckless individuals who threw Shadrach, Meschach, and Abednego into the seven-times heated furnace, Miselle stooped, and, looking in, uttered a cry of surprise and delight.

It was the very soul of fire, the essence of light and heat. Above, rose a glowing arch, quivering with an intensity of color, such as fascinates the eye of the eagle to the noonday sun. Below, undulated in great oily waves a sea of molten matter, throbbing in vivid curves against the sides of its glowing basin. And arch and wall and heaving waves all mingled in a pure harmony, an accord, of light too intense for color, or rather a color so intense as to be nameless in this pale world.

Miselle knew now how the moth feels who plunges wildly into the flame that lures him to his death, and yet fascinates him beyond the power of resistance. The door was very small, or it might have been already too late, when Optima touched the shoulder of this modern Parsee, and suggested, calmly,—

"If you burn your eyes out here, my dear Miselle, you will be unable to see anything else."

The thought was a kind and sensible one, as, coming from Optima, it could not have failed of being; and Miselle stood upright, stared forlornly about her, and found the world very pale and weak, very cold and dark.

Was it to solace her sudden exile from fairy-land, or was it only as a customary courtesy, that an old man, wasted and paled by years of ministration at this fiery shrine, now seized a long, hollow iron rod, called a blow-stick, and, thrusting the smaller end into the pot, withdrew a small portion of the glass, and, while retaining it by a swift twirl, presented the mouth-piece of the tube to Miselle with a gesture so expressive that she immediately applied her lips to those of the blow-stick, and rounded her cheeks to the similitude of those corpulent little Breezes whom the old masters are so fond of depicting attendant upon the flight of their brothers the Winds?

Ah, my little dears, with your straws and soap-suds you will never blow a bubble like that! As it slowly rounded to its perfect sphere, what secrets of its birth within that glowing furnace, what mysteries of the pure element whose creation it seemed, flashed in fiery hieroglyph athwart its surface! A mocking globe, whereon were painted realms that may none the less exist, because man's feeble vision has never seen them, his fettered mind never imagined them. Who knows? It may have been the surface of the sun that was for one instant drawn upon that ball of liquid fire. Who is to limit the affinities, the subtle reproductions of Nature's grand ideas?

But as the wonder culminated, as the glancing rays resolved themselves into more positive lines, as the enigma seemed about to offer its own solution, the bubble broke, flew into a myriad tiny shards, which, with a tinkling laugh, fell to the grimy pavement, and lay there sparkling malicious fun into Miselle's eyes.

Cicerone stooped and gathered some of the fragments. Surely, never was substance so closely allied to shadow. The lightest touch, a breath even, and they were gone,—and were they caught, it was like the capture of one of the floating films of a summer morning, glancing brightly to the eye, but impalpable to the touch.

When all had looked, the guide slowly closed his hand with a cruel gripe, and, opening it, threw down a little shower of scintillating dust, an airy fall of powdered diamonds, lost as they readied the earth, and that was all.

"We're casting some of those Fresnel lanterns to-day. Perhaps the ladies would like to see them," suggested the pale little old man, and pointed to a powerful machine with a long lever-handle at the top, which, being thrown up, showed a heavy iron mould, heated quite hot, and just now smoking furiously from a fresh application of kerosene-oil, with which the mould is coated before each period of service, much as the housewife butters her griddle before each plateful of buckwheat cakes.

As the smoke subsided, the old man, who proved a very intelligent as well as civil person, thrust his pontil into the pot nearest the press, and, withdrawing a sufficient quantity of the glass, dropped it squarely into the open mould, whose operator, immediately seizing the long handle, swung himself from it in a grotesque effort to increase the natural gravity of his body, and succeeded in bringing it down with great force. Then, leaning over the lever in a state of complacent exhaustion, he glared for a moment at the spectators with the calm superiority of one who, having climbed to the summit of knowledge, can afford to pity the ignorant crowd groping below.

The mould being reopened presently displayed a large, heavy lantern, whose curiously elaborate flutings and pencillings were, as the intelligent artisan averred, arranged upon the principle of the famous Fresnel light, whose introduction some years ago marked an epoch in the history of light-houses.