Полная версия

Полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 07, No. 43, May, 1861

Among the Turtles is Emys picta, Chelonura serpentina, and Cistuda clausa.

Of the Frogs, we have Rana sylvatica, Rana palustris, and Rana pipiens, nearly two feet long, and loud-voiced in proportion,—a Bull-Frog, indeed!

Various theories and speculations have been formed as to the origin of the prairies. One of them, is, that the forests which formerly occupied these plains were swept away at some remote period by fire; and that the annual fires set by the Indians have continued this state of things. Another theory is, that the violent winds which sweep over them have prevented the growth of trees; a third, that want of rain forbids their growth; a fourth, that the agency of water has produced the effect; and lastly, a learned professor at the last meeting of the Scientific Convention put forth his theory, which was, that the real cause of the absence of trees from the prairies is the mechanical condition of the soil, which is, he thinks, too fine,—a coarse, rocky soil being, in his estimation, a necessary condition of the growth of trees.

Most of these theories seem to be inconsistent with the plain facts of the case. First, we know that these prairies existed in their present condition when the first white man visited them, two hundred years ago; and also that similar treeless plains exist in South America and Central Africa, and have so existed ever since those countries were known. We are told by travellers in those regions, that the natives have the same custom of annually burning the dry grass and herbage for the same reason that our Indians did it, and that the early white settlers kept up the custom,—namely, to promote the growth of young and tender feed for the wild animals which the former hunted and the cattle which the latter live by grazing.

Another fact, well known to all settlers in the prairie, is, that it is only necessary to keep out the fires by fences or ditches, and a thick growth of trees will spring up on the prairies. Many fine groves now exist all over Illinois, where nothing grew twenty years ago but the wild grasses and weeds; and we have it on record, that locust-seed, sown on the prairie near Quincy, in four years produced trees with a diameter of trunk of four to six inches, and in seven years had become large enough for posts and rails. So with fruit-trees, which nowhere flourish with more strength and vigor than in this soil,—too much so, indeed, since they are apt to run to wood rather than fruit. Moreover, the soil in the groves and on the river bottoms, where trees naturally grow, is the same, chemically and mechanically, as that of the open prairie; the same winds sweep over both, and the same rain falls upon both; so that it would seem that the absence of trees cannot be attributed wholly to fire, water, wind, or soil, but is owing to a combination of two or more of those agencies.

But from whatever cause the prairies originated, they have no doubt been perpetuated by the fires which annually sweep over their surface. Where the soil is too wet to sustain a heavy growth of grass, there is no prairie. Timber is found along the streams, almost invariably,—and, where the banks are high and dry, will usually be found on the east bank of those streams whose course is north and south. This is caused by the fact that the prevailing winds are from the west, and bring the fire with them till it reaches the stream, which forms a barrier and protects the vegetation on the other side.

If any State in the Union is adapted to agriculture, and the various branches of rural economy, such as stock-raising, wool-growing, or fruit-culture, it must surely be Illinois, where the fertile natural meadows invite the plough, without the tedious process of clearing off timber, which, in many parts of the country, makes it the labor of a lifetime to bring a farm under good cultivation. Here, the farmer who is satisfied with such crops as fifty bushels of corn to the acre, eighteen of wheat, or one hundred of potatoes, has nothing to do but to plough, sow, and reap; no manure, and but little attention, being necessary to secure a yield like this. Hence a man of very small means can soon become independent on the prairies. If, however, one is ambitious of raising good crops, and doing the best he can with his land, let him manure liberally and cultivate diligently; nowhere will land pay for good treatment better than here.

Mr. J. Ambrose Wight, of Chicago, the able editor of the "Prairie Farmer," writes as follows:—

"From an acquaintance with Illinois lands and Illinois farmers, of eighteen years, during thirteen of which I have been editor of the 'Prairie Farmer,' I am prepared to give the following as the rates of produce which may be had per acre, with ordinary culture:—

Winter Wheat, 15 to 25 Bushels.

Spring " 10 to 20 "

Corn, 40 to 70 "

Oats, 40 to 60 "

Potatoes, 100 to 200 "

Grass, Timothy and Clover, 1-1/2 to 3 Tons.

"Ordinary culture, on prairie lands, is not what is meant by the term in the Eastern or Middle States. It means here, no manure, and commonly but once, or at most twice, ploughing, on perfectly smooth land, with long furrows, and no stones or obstructions; where two acres per day is no hard job for one team. It is often but very poor culture, with shallow ploughing, and without attention to weeds. I have known crops, not unfrequently, far greater than these, with but little variation in their treatment: say, 40 to 50 bushels of winter wheat, 60 to 80 of oats, and 100 of Indian corn, or 300 of potatoes. Good culture, which means rotation, deep ploughing, farms well stocked, and some manure applied at intervals of from three to five years, would, in good seasons, very often approach these latter figures."

We will now give the results of a very detailed account of the management of a farm of 240 acres, in Kane County, Illinois, an average farm as to soil and situation, but probably much above the average in cultivation,—at least, we should judge so from the intelligent and business-like manner in which the account is kept; every crop having a separate account kept with it in Dr. and Cr., to show the net profit or loss of each.

23 acres of Wheat, 30 bushels per acre, net profit $453.00 17-1/2 " " on Corn ground, 22-1/2 " " " 278.50 9-1/2 " Spring Wheat, 24 " " " 159.70 2-1/2 " Winter Rye, 22-7/12 " " " 10.25 5-1/2 " Barley, 33-1/4 " " " 32.55 12 " Oats, 87-1/2 " " " 174.50 28-1/2 " Corn, 60 " " " 638.73 1 " Potatoes, 150 " " " 27.50 103 Sheep, average weight of fleece, 3-1/2 lbs., " 177.83 15 head of Cattle and one Colt " 103.00 1500 lbs. Pork " 35.00 Fruit, Honey, Bees, and Poultry " 73.75 21 acres Timothy Seed, 4 bushels per acre, " 123.00 – $2287.31

A farm of this size, so situated, with the proper buildings and stock, may, at the present price of land, be supposed to represent a capital of $15,000—on which sum the above account gives an interest of over 15 per cent. Is there any other part of the country where the same interest can be realized on farming capital?

But this farm of 240 acres is a mere retail affair to many farms in the State. We will give some examples on a larger scale.

"Winstead Davis came to Jonesboro', Illinois, from Tennessee, thirty years ago, without means of any kind; now owns many thousand acres of land, and has under cultivation, this year, from 2500 to 3000 acres."

"W. Willard, native of Vermont, commenced penniless; now owns more than 10,000 acres of land, and cultivates 2000."

"Jesse Funk, near Bloomington, Illinois, began the world thirty years ago, at rail-splitting, at twenty-five cents the hundred. He bought land, and raised cattle; kept increasing his lands and herds, till he now owns 7000 acres of land, and sells over 840,000 worth of cattle and hogs annually.

"Isaac Funk, brother of the above, began in the same way, at the same time. He has gone ahead of Jesse; for he owns 27,000 acres of land, has 4000 in cultivation, and his last year's sales of cattle amounted to $65,000."

It is evident that the brothers Funk are men of administrative talent; they would have made a figure in Wall Street, could have filled cabinet office at Washington, or, perhaps, could even have "kept a hotel."

These are but specimens of the large-acred men of Illinois. Hundreds of others there are, who farm on nearly the same scale.

The great difficulty in carrying on farming operations on a large scale in Illinois has always been the scarcity of labor. Land is cheap and plenty, but labor scarce and dear: exactly the reverse of what obtains in England, where land is dear and labor cheap. It must be evident that a different kind of farming would be found here from that in use in older countries. There, the best policy is to cultivate a few acres well; here, it has been found more profitable to skim over a large surface. But within a few years the introduction of labor-saving machines has changed the conditions of farming, and has rendered it possible to give good cultivation to large tracts of land with few men. Many of the crops are now put in by machines, cultivated by machines, and harvested by machine. If, as seems probable, the steam-plough of Fawkes shall become a success, the revolution in farming will be complete. Already some of the large farmers employ wind or steam power in various ways to do the heavy work, such as cutting and grinding food for cattle and hogs, pumping water, etc.

Although the soil and climate of Illinois are well adapted to fruit-culture, yet, from various causes, it has not, till lately, been much attended to. The early settlers of Southern and Middle Illinois were mostly of the Virginia race, Hoosiers,—who are a people of few wants. If they have hog-meat and hominy, whiskey and tobacco, they are content; they will not trouble themselves to plant fruit-trees. The early settlers in the North were, generally, very poor men; they could not afford to buy fruit-trees, for the produce of which they must wait several years. Wheat, corn, and hogs were the articles which could be soonest converted into money, and those they raised. Then the early attempts at raising fruit were not very successful. The trees were brought from the East, and were either spoiled by the way, or were unsuited to this region. But the great difficulty has been the want of drainage. Fruit-trees cannot be healthy with wet feet for several months of the year, and this they are exposed to on these level lands. With proper tile-draining, so that the soil shall be dry and mellow early in the spring, we think that the apple, the pear, the plum, and the cherry will succeed on the prairies anywhere in Illinois. The peach and the grape flourish in the southern part of the State, already, with very little care; in St. Clair County, the culture of the latter has been carried on by the Germans for many years, and the average yield of Catawba wine has been two hundred gallons per acre. The strawberry grows wild all over the State, both in the timber and the prairie; and the cultivated varieties give very fine crops. All the smaller fruits do well here, and the melon family find in this soil their true home; they are raised by the acre, and sold by the wagon-load, in the neighborhood of Chicago.

Stock-raising is undoubtedly the most profitable kind of farming on the prairies, which are so admirably adapted to this species of rural economy, and Illinois is already at the head of the cattle-breeding States. There were shipped from Chicago in 1860, 104,122 head of live cattle, and 114,007 barrels of beef.

The Durham breed seems to be preferred by the best stock-farmers, and they pay great attention to the purity of the race. A herd of one hundred head of cattle raised near Urbanna, and averaging 1965 pounds each, took the premium at the World's Fair in New York. Although the Durhams are remarkable for their large size and early maturity, yet other breeds are favorites with many farmers,—such as the Devons, the Herefords, and the Holsteins, the first particularly,—for working cattle, and for the quality of their beef. There is a sweetness about the beef fattened upon these prairies which is not found elsewhere, and is noticed by all travellers who have eaten of that meat at the best Chicago hotels.

In fact, Illinois is the paradise of cattle, and there is no sight more beautiful, in its way, than one of those vast natural meadows in June, dotted with the red and white cattle, standing belly-deep in rich grass and gay-colored flowers, and almost too fat and lazy to whisk away the flies. Even in winter they look comfortable, in their sheltered barn-yard, surrounded by huge stacks of hay or long ranges of corn-cribs, chewing the cud of contentment, and untroubled with any thought of the inevitable journey to Brighton.

Where corn is so plenty as it is in Illinois, of course hogs will be plenty also. During the year 1860, two hundred and seventy-five thousand porkers rode into Chicago by railroad, eighty-five thousand of which pursued their journey, still living, to Eastern cities,—the balance remaining behind to be converted into lard, bacon, and salt pork.

The wholesale way of making beef and pork is this. All summer the cattle are allowed to run on the prairie, and the hogs in the timber on the river bottoms. In the autumn, when the corn is ripe, the cattle are turned into one of those great fields, several hundred acres in extent, to gather the crop; and after they have done, the hogs come in to pick up what the cattle have left.

Sheep do well on the prairies, particularly in the southern part of the State, where the flocks require little or no shelter in winter. The prairie wolves formerly destroyed many sheep; but since the introduction of strychnine for poisoning those voracious animals, the sheep have been very little troubled.

Horses and mules are raised extensively, and in the northern counties, where the Morgans and other good breeds have been introduced, the horses are as good as in any State of the Union. Theory would predict this result, since the horse is found always to come to his greatest perfection in level countries,—as, for instance, the deserts of Arabia, and the llanos of South America.

There are two articles in daily and indispensable use, for which the Northern States have hitherto been dependent on the Southern: Sugar and Cotton. With regard to the first, the introduction of the Chinese Sugar-Cane has demonstrated that every farmer in the State can raise his own sweetening. The experience of several years has proved that the Sorghum is a hardier plant than corn, and that it will be a sure crop as far North as latitude 42° or 43°.

An acre of good prairie will produce 18 tons of the cane, and each ton gives 60 gallons of juice, which is reduced, by boiling, to 10 gallons of syrup. This gives 180 gallons of syrup to the acre, worth from 40 to 50 cents a gallon,—say 40 cents, which will give 72 dollars for the product of an acre of land; from which the expenses of cultivation being deducted, with rent of land, etc., say 36 dollars, there will remain a net profit of 36 dollars to the acre, besides the seed, and the fodder which comes from a third part of the stalk, which is cut off before sending the remainder to the mill. This is found to be the most nutritious food that can be used for cattle and horses, and very valuable for milch cows. These results Lave been obtained from Mr. Luce, of Plainfield, Will County, who has lately built a steam-mill for making the syrup from the cane which is raised by the farmers in that vicinity. In this first year, he manufactured 12,500 gallons of syrup, which sells readily at fifty cents a gallon. A quantity of it was refined at the Chicago Sugar-Refinery, and the result was a very agreeable syrup, free from the peculiar flavor which the home-made Sorghum-syrup usually has. As yet, no experiments on a large scale have been made to obtain crystallized sugar from the juice of this cane, it having been, so far, used more economically in the shape of syrup. That it can be done, however, is proved by the success of several persons who have tried it in a small way. In the County of Vermilion, it is estimated that three hundred thousand gallons of syrup were made in 1860.

As to Cotton, since the building of the Illinois Central Railroad has opened the southern part of the State to the world, and let in the light upon that darkened Egypt, it is found that those people have been raising their own cotton for many years, from the seed which they brought with them into the State from Virginia and North Carolina. The plant has become acclimated, and now ripens its seed in latitude 39° and 40°. Perhaps the culture may be carried still farther, so that cotton may be raised all over the State. The heat of our summers is tropical, but they are too short. If, however, the cotton-plant, like Indian corn and the tomato, can be gradually induced to mature itself in four or five months, the consequences of such a change can hardly be estimated.

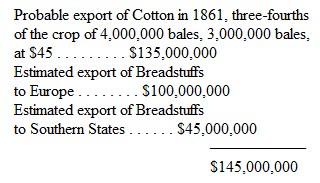

But whether or not it be possible to raise cotton and sugar profitably in Illinois, that she is the great bread- and meat-producing State no one can doubt; and in 1861 it happens that Cotton is King no longer, but must yield his sceptre to Corn.

The breadstuffs exported from the Northwest to Europe and to the Cotton States will this year probably amount to more money than the whole foreign export of cotton,—the crop which to some persons represents all that the world contains of value.

We are feeding Europe and the Cotton States, who pay us in gold; we feed the Northern States, who pay us in goods; we are feeding our starving brothers in Kansas, who have paid us beforehand, by their heroic devotion to the cause of freedom. Let us hope that their troubles are nearly over, and that, having passed through more hardships than have fallen to the lot of any American community, they may soon enter upon a career of prosperity as signal as have been their misfortunes, so that the prairies of Kansas may, in their turn, assist in feeding the world.

Nothing has done so much for the rapid growth of Illinois as her canal and railroads.

As early as 1833 several railroad charters were granted by the legislature; but the stock was not taken, and nothing was done until the year 1836, when a vast system of internal improvements was projected, intended "to be commensurate with the wants of the people,"—that is, there was to be a railroad to run by every man's door. About thirteen hundred miles of railroads were planned, a canal was to be built from Chicago to the Illinois River at Peru, and several rivers were to be made navigable. The cost of all this it was supposed would be about eight millions of dollars, and the money was to be raised by loan. In order that all might have the benefit of this system, it was provided that two hundred thousand dollars should be distributed among those counties where none of these improvements were made. To cap the climax of folly, it was provided that the work should commence on all these roads simultaneously, at each end, and from the crossings of all the rivers.

As no previous survey or estimate had been made, either of the routes, the cost of the works, or the amount of business to be done on them, it is not surprising that the State of Illinois soon found herself with a heavy debt, and nothing to show for it, except a few detached pieces of railroad embankments and excavations, a half-finished canal, and a railroad from the Illinois River to Springfield, which cost one million of dollars, and when finished would not pay for operating it.

The State staggered on for some ten years under this load of debt, which, as she could not pay the interest upon it, had increased in 1845 to some fourteen millions. The project of repudiating the debt was frequently brought forward by unscrupulous politicians; but to the honor of the people of Illinois be it remembered, that even in the darkest times this dishonest scheme found but few friends.

In 1845, the holders of the canal bonds advanced the sum of $1,700,000 for the purpose of finishing the canal; and subsequently, William B. Ogden and a few other citizens of Chicago, having obtained possession of an old railroad-charter for a road from that city to Galena, got a few thousand dollars of stock subscribed in those cities, and commenced the work. The difficulties were very great, from the scarcity of money and the want of confidence in the success of the enterprise. In most of the villages along the proposed line there was a strong opposition to having a railroad built at all, as the people thought it would be the ruin of their towns. Even in Chicago, croakers were not wanting to predict that the railroad would monopolize all the trade of the place.

In the face of all these obstacles, the road was built to the Des Plaines River, twelve miles,—in a very cheap way, to be sure; as a second-hand strap-rail was used, and half-worn cars were picked up from Eastern roads.

These twelve miles of road between the Des Plaines and Chicago had always been the terror of travellers. It was a low, wet prairie, without drainage, and in the spring and autumn almost impassable. At such seasons one might trace the road by the broken wagons and dead horses that lay strewn along it.

To be able to have their loads of grain carried over this dreadful place for three or four cents a bushel was to the farmers of the Rock River and Fox River valleys—who, having hauled their wheat from forty to eighty miles to this Slough of Despond, frequently could get it no farther—a privilege which they soon began to appreciate. The road had all it could do, at once. It was a success. There was now no difficulty in getting the stock taken up, and before long it was finished to Fox River. It paid from fifteen to twenty per cent to the stockholders, and the people along the line soon became its warmest friends,—and no wonder, since it doubled the value of every man's farm on the line. The next year the road was extended to Rock River, and then to Galena, one hundred and eighty-five miles.

This road was the pioneer of the twenty-eight hundred and fifty miles of railroads which now cross the State in every direction, and which have hastened the settlement of the prairies at least fifty years.

Among these lines of railway, the most important, and one of the longest in America, is the Illinois Central, which is seven hundred and four miles in length, and traverses the State from South to North, namely:—

1. The main line, from Cairo to La Salla 308 miles 2. The Galena Branch, from La Salle to Dunleith 146 " 3. The Chicago Branch, from Chicago to Centralia 250 "

This great work was accomplished in the short space of four years and nine months, by the help of a grant of two and a half millions of acres of land lying along the line. The company have adopted the policy of selling these lands on long credit to actual settlers; and since the completion of the road, in 1856, they have sold over a million of acres, for fifteen millions of dollars, in secured notes, bearing interest. The remaining lands will probably realize as much more, so that the seven hundred and four miles of railroad will actually cost the corporators nothing.

There are eleven trunk and twenty branch and extension lines, which centre in Chicago, the earnings of nineteen of which, for the year 1859, were fifteen millions of dollars. As that, however, was a year of great depression in business, with a short crop through the Northwest, we think, in view of the large crop of 1860, and the consequent revival of business, that the earnings of these nineteen lines will not be less this year than twenty-two millions of dollars.

In the early settlement of the State, twenty-five or thirty years ago, the pioneers being necessarily very liable to want of good shelter, to bad food and impure water, suffered much from bilious and intermittent fevers. As the country has become settled, the land brought under cultivation, and the habits of the people improved, these diseases have in a great measure disappeared. Other forms of disease have, however, taken their place, pulmonary affections and fevers of the typhoid type being more prevalent than formerly; but as most of the immigrants into Northern Illinois are from Western New York and New England, where this latter class of diseases prevails, the people are much less alarmed by them than they used to be by the bilious diseases, though the latter were really less dangerous. The coughs, colds, and consumptions are old acquaintances, and through familiarity have lost their terrors.