Полная версия

Полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 67, February 8, 1851

Query, Did Anna Boleyn, wife of Henry VIII., ever spell her name so? I need not to be reminded that some lexicographers define "Blowen" to be a rude woman. Query, origin of that appellation, so used?

We have been citizens and liverymen of London from Richard Blowen, who married, at the close of the seventeenth century, the sister of Dr. Hugh Boulter (who became chaplain to George I., and afterwards Lord Archbishop of Armagh).

Blowen.Replies

TOUCHSTONE'S DIAL

(Vol. ii., p. 405.; vol. iii., p. 52.)How is it that Mr. Knight, who so well and so judiciously exposes the absurdness of attempting to measure out a poet's imaginings by rule-and-compass probability, should himself endeavour to embody and identify Touchstone's dial—an ideal image—a mere peg on which to hang the fool's sapient moralizing.

Surely, whether it was a real moving animated pocket watch, that was present to the poet's mind, or a thumb ring dial, is an inquiry quite as bootless as the geographical existence of a sea-coast in Bohemia, or of lions and serpents in the forest of Ardennes.

When Thaliard engages to take away the life of Pericles if he can get him within his "pistol's length," are we seriously to inquire whether the weapon was an Italian dagger or an English firearm? or are we to debate which of the interpretations would be the lesser anachronism?

But your correspondents (Vol. ii., p. 405. and vol. iii., p. 52.) approve of, and confirm Mr. Knight's suggestion of a ring dial, as though it were so self-evident as to admit of no denial. Nevertheless, neither he nor they have shown any good reason for its adoption: even its superior antiquity over the portable time-piece is mere surmise on their parts, unaccompanied as yet by any direct proof. In point of fact, the sole argument advanced by Mr. Knight why Touchstone's dial should be a ring dial is, that "it was not likely that the fool would have a pocket watch." Well, but it might belong to Celia, carried away with the "jewels and wealth" she speaks of, and, on account of the unwieldy size of watches in those days, intrusted to the porterage of the able-bodied fool.

When Touchstone said, so very wisely, "It is ten o'clock," he used a phrase which, according to Orlando in the same play, could only properly apply to a mechanical time-piece. Rosalind asks Orlando, "I pray you what is it a clock?" to which he replies, "You should ask me what time o' day; there's no clock in the forest." Again, when Jacques declares that he did laugh "an hour by his dial," do we not immediately recall Falstaff's similar phrase, "an hour by Shrewsbury clock?"

If it shall be said that the word "dial" is more used in reference to a natural than to a mechanical indicator of time, I should point, in reply, to Hotspur's allusion:

"Tho' life did ride upon a dial's pointStill ending with the arrival of an hour"The "dial's point," so referred to, must be in motion, and is therefore the hand or pointer of a mechanical clock.

A further confirmation that the Shakspearian "dial" was a piece of mechanism may be seen in Lafeu's reply to Bertram, when he exclaims,

"Then my dial goes not true,"

using it as a metaphor to imply that his judgment must have been deceived.

These are some of the considerations that would induce me to reject Mr. Knight's interpretation, and, were it necessary to realize the scene between Jacques and Touchstone at all, I should prefer doing so by imagining some old turnip-faced atrocity in clock-making presented to the fool's lack-lustre eye, than the nice astronomical observation supposed by Mr. Knight.

The ring-dial, as described by him, and by your correspondents, is likewise described in most of the encyclopædias. It is available for the latitude of construction only, and was no doubt common enough a hundred years ago; but it is scarcely an object as yet for deposit in the British Museum.

A. E. B.Leeds, Jan. 28. 1851.

The Ring Dial, perhaps the most elegant in principle of all the forms of sun dial, has not, I think, fallen into greater disuse than have sun dials of other constructions. To describe, in this place, a modern ring dial, and the method of using it, would be useless: because it is an instrument which may be so readily inspected in the shops of most of the London opticians. Messrs. Troughton and Simms, of Fleet Street, make ring dials to a pattern of about six inches in diameter, costing, in a case, 2l. 5s. They are, in truth, elegant and instructive astronomical toys, to say the least of them; and indicate the solar time to the accuracy of about two minutes, when the sun is pretty high.

Formerly, ring dials were made of a larger diameter, with much costly graduation bestowed upon them; too heavy to be portable, and too expensive for the occasion. For example, at the apartments of the Royal Astronomical Society, at Somerset House, a ring dial, eighteen inches in diameter, may be seen, constructed by Abraham Sharp, contemporary and correspondent of Newton and Flamstead; one similar to which, hazarding a guess, I should say, could not be made under 100l. At the same place also may be seen, belonging to Mr. Williams, the assistant-secretary of the society, a very handsome oriental astrolabe, about four inches in diameter, richly chased with Arabic characters and symbols; to which instrument, as well as to modern ring dials, the ring dials described in "Notes and Queries" (Vol. iii., p. 52.) seem to bear relation. If I recollect right, in one of the tales of the Arabian Nights, the barber goes out, leaving his customer half shaved, to take an observation with his astrolabe, to ascertain if he were operating in a lucky hour. By his astrolabe, therefore, the barber could find the time of day; this, however, I confess I could not pretend to find with the astrolabe in question. Ring dials, as I am informed, are in demand to go out to India, where they are in use among surveyors and military men; and, no doubt, such instruments as the astrolabe above-mentioned, which, though pretty old, does not pretend to be an antique, are in use among the educated of the natives all over the East.

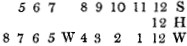

Robert Snow.I send you the particulars of two brass ring dials, seeing they are claiming some notice from your learned correspondents, and having recently bought them of a dealer in old metals.

7-16ths of an inch wide, 1 and 7-16ths over,

3-8ths wide, and 1½ over,

Easton, Jan. 27. 1851.

WINIFREDA

(Vol. ii., p. 519. Vol. iii., p. 27.)Subjoined is a brief notice of the various printed forms in which the old song called "Winifreda" has, from time to time, been brought before the public. I am indebted for these particulars to a kind friend in the British Museum, but we have hitherto failed in discovering the author.

1. The song first occurs as a translation from the ancient British language in D. Lewis's Collection of Miscellaneous Poems, 8vo. 1726, vol. i., p. 53., pointed out by your correspondent, Mr. Hickson. (Vol. ii., p. 519.)

2ndly. In Watts' Musical Miscellany, vol. vi., p. 198. Lond. 1731; it is with the tune, "Eveillez vous ma belle Endormie," and is called "Winifreda, from the ancient language."

3dly. As an engraved song entitled "Colin's Address;" the words by the Earl of Chesterfield, set by W. Yates, 1752. The air begins "Away, &c."

4thly. In 1755, 8vo., appeared Letters concerning Taste, anonymously, but by John Gilbert Cooper; in Letter XIV. pp. 95, 96, he says,—

"It was not in my power then to amuse you with any poetry of my own composition, I shall now take the liberty to send you, without any apology, an old song wrote above a hundred years ago by the happy bridegroom himself."

Cooper then praises the poem, and prints it at length.

5thly. In 1765, Dr. Percy first published his Reliques, with the song, as copied from Lewis.

6thly. We find an engraved song, entitled "Winifreda, an Address to Conjugal Love," translated from the ancient British language; set to music by Signor Giordani, 1780. The air begins, "Away, &c."

7thly. In Ritson's printed Songs as by Gilbert Cooper, Park's edition, 1813, vol. i., p. 281., with a note by the editor referring to Aikin's Vocal Biography, p. 152.; and mentioning that in the Edinburgh Review, vol. xi., p. 37. "Winifreda" is attributed to the late Mr. Stephens, meaning George Steevens.

8thly. In Campbell's British Poems, 1819, vol. vi., p. 93., with a Life of John Gilbert Cooper, to whom Campbell attributes the authorship, stating that he was born in 1723, and died in 1769; he was, consequently, only three years old when the poem was printed, which would settle the question, even if his disclaimer had been merely a trick to deceive his friend.

Lord Chesterfield's claim is hardly worth notice; his name seems to have been used to promote the sale of the "Engraven old Song;" and no one can doubt that he would gladly have avowed a production which would have added to his literary fame.

Whether the problem will ever be solved, seems very doubtful; but I am disposed to think that the song belongs to a much earlier period, and that it should be looked for amongst the works of those poets of whom Izaak Walton has left us such agreeable reminiscences; and whose simplicity and moral tone are in keeping with those sentiments of good feeling to which "Winifreda" owes its principal attraction.

Braybrooke.Audley End.

Winifreda (Vol. iii., p. 27.).—Lord Braybrooke has revived a Query which I instituted above forty years ago (see Gent.'s Magazine for 1808, vol. lxxviii., Part I. p. 129.). The correspondent, C. K., who replied to my letter in the same magazine, mentioned the appearance of this song in Dodsley's Letters on Taste (3rd edition, 1757.) These letters, being edited by John Gilbert Cooper, doubtless led Aikin, in his collection of songs, and Park, in his edition of Ritson's English Songs, to ascribe it to Cooper. That writer speaks of it as an "old song," and with such warm praise, that we may fairly suppose it was not his own production. C. K. adds, from his own knowledge, that about the middle of the eighteenth century, he well remembered a Welsh clergyman repeating the lines with spirit and pathos, and asserting that they were written by a native of Wales. The name of Winifreda gives countenance to this; and the publication by David Lewis, in 1726, referred to by Bishop Percy, as that in which it first appeared, also connects the song with the principality. An Edinburgh reviewer (vol. xi. p. 37.) says that it is "one of the love songs" by Stephens (meaning George Steevens), a strange mistake, as the poem appeared in print ten years before Steevens was born.

I notice this error for the purpose of asking your readers whether many poems by this clever, witty, and mischievous writer exist, although not, to use the words of the reviewer, "in a substantive or collective form?" "The Frantic Lover," referred to in the Edinburgh Review, and considered by his biographer as "superior to any similar production in the English language," and the verses on Elinor Rummin, are the only two poems of George Steevens which now occur to me; but two or three others are noticed in Nichols's Literary Anecdotes as his productions.

J. H. M.Replies to Minor Queries

Did St. Paul's Clock strike Thirteen? (Vol. iii., p. 40.).—Mr. Campkin will find some notice of the popular tradition to which he refers, in the Antiquarian Repertory, originally published in 1775, and republished in 1807; but I doubt whether it will satisfactorily answer his inquiries.

I. H. M.By the bye (Vol. ii., p. 424.).—As no one of your correspondents has answered the Query of J. R. N., as to the etymology and meaning of by the bye and by and by, I send you the following exposition; which I have collected from Richardson's Dictionary, and the authorities there referred to.

Spelman informs us, that in Norfolk there were in his time thirteen villages with names ending in by: this By being a Danish word, signifying "villa." That a bye-law, Dan. by-lage, is a law peculiar to a villa. And thus we have the general application of bye to any thing; peculiar, private, indirect, as distinguished from the direct or main: as, bye-ways, bye-talk, &c. &c. In the trial of Sir Walter Raleigh, State Trials, James I., 1603, are these words:—

"You are fools; you are on the bye, Raleigh and I are on the main. We mean to take away the king and his cubs."

Here the contradistinction is manifest. Lord Bacon and B. Jonson write, on the by; as if, on the way, in passing, indirectly:—

"'There is, upon the by, to be noted.'—'Those who have seluted poetry on the by'—such being a collateral, and not the main object of pursuit."

This I think is clear and satisfactory.

By and by is quite a different matter. Mr. Tyrwhitt, upon the line in Chaucer,—

"These were his words by and by."—R. R. 4581.

interprets "separately, distinctly;" and there are various other instances in Chaucer admitting the same interpretation:—

"Two yonge knightes ligging, by and by."—Kn. T., v. 1016."His doughter had a bed all by hireselve,Right in the same chambre by and by."—The Reves T., v. 4441.So also in the "Floure and the Leafe," stanzas 9 and 24. The latter I will quote, as it is much to the purpose:—

"The semes (of the surcote) echon,As it were a maner garnishing,Was set with emerauds, one and one,By and by."But there are more ancient usages, e.g. in R. Brunne, bearing also the same interpretation. "The chartre was read ilk poynt bi and bi:" William had taken the homage of barons "bi and bi." He assayed (i.e. tried) "tham (the horses) bi and bi."

Richardson's conception is, that there is a subaudition in all these expressions; and that the meaning is, by point and by point; by baron and by baron; by horse and by horse: one and one, as Chaucer writes; each one separately, by him or it-self. And thus, that by and by may be explained, by one and by one; distinctly, both in space or time. Our modern usage is restricted to time, as, "I will do so by and by:" where by and by is equivalent to anon, i.e. in one (moment, instant, &c.). And so—

Good B'ye.Bloomsbury.

Clement's Inn (Vol. iii., p. 84.).—This inn was neither "a court of law" nor "an inn of court," but "an inn of chancery;" according to the distinction drawn by Sir John Fortescue, in his De Laudibus Legum Angliæ, chap. xlix., written between 1460 and 1470.

The evidence of its antiquity is traced back to an earlier date than 1486; for, according to Dugdale (Orig., p. 187.), in a Record of Michaelmas, 19 Edward IV., 1479, it is spoken of as then, and diu ante, an Inn "hominum Curiæ Legis temporalis, necnon hominum Consiliariorum ejusdem Legis."

The early history of the Inns of Court and Chancery is involved in the greatest obscurity; and it is difficult to account for the original difference between the two denominations.

Any facts which your correspondents may be able to communicate on this subject, or in reference to what were the ten Inns of Chancery existing in Fortescue's time, but not named by him, or relating to the history of either of the Inns, whether of Court or Chancery, will be most gratefully received by me, and be of important service at the present time, when I am preparing for the press my two next volumes of The Judges of England.

Edward Foss.Street-End House, near Canterbury.

Words are men's daughters (Vol. iii., p. 38.).—I take this to be a proverbial sentence. In the Gnomologia of Fuller we have "Words are for women; actions for men"—but there is a nearer approach to it in a letter written by Sir Thomas Bodley to his librarian about the year 1604. He says,

"Sir John Parker hath promised more than you have signified: but words are women, and deeds are men."

It was no doubt an adoption of the worthy knight, and I shall leave it to others to trace out the true author—hoping it may never be ascribed to an ancestor of

Bolton Corney.Passage in St. Mark (Vol. iii., p. 8.).—Irenæus is considered the best (if not the only) commentator among the very early Fathers upon those words in Mark xiii. 32. "οὐδὲ ὁ υἱὸς;" and though I cannot refer Calmet further than to the author's works, he can trust the general accuracy of the following translation:—

"Our Lord himself," says he, "the Son of God, acknowledged that the Father only knew the day and hour of judgment, declaring expressly, that of that day and hour knoweth no one, neither the Son, but the Father only. Now, if the Son himself was not ashamed to leave the knowledge of that day to the Father, but plainly declared the truth; neither ought we to be ashamed to leave to God such questions as are too high for us. For if any one inquires why the Father, who communicates in all things to the Son, is yet by our Lord declared to know alone that day and hour, he cannot at present find any better, or more decent, or indeed any other safe answer at all, than this, that since our Lord is the only teacher of truth, we should learn of him, that the Father is above all; for the Son saith, 'He is greater than I.' The Father, therefore, is by Our Lord declared to be superior even in knowledge also; to this end, that we, while we continue in this world, may learn to acknowledge God only to have perfect knowledge, and leave such questions to him; and (put a stop to our presumption), lest curiously inquiring into the greatness of the Father, we run at last into so great a danger, as to ask whether even above God there be not another God."

Blowen."And Coxcombs vanquish Berkeley by a Grin" (Vol. i., p. 384.).—This line is taken from Dr. Brown's Essay on Satire, part ii. v. 224. The entire couplet is—

"Truth's sacred fort th' exploded laugh shall win,And coxcombs vanquish Berkeley by a grin."Dr. Brown's Essay is prefixed to Pope's "Essay on Man" in Warburton's edition of Pope's Works. (See vol. iii. p. 15., edit. 1770, 8vo.)

Dr. Trusler's Memoirs (Vol. iii., p. 61.).—The first part of Dr. Trusler's Memoirs (Bath, 1806), mentioned by your correspondent, but which is not very scarce, is the only one published. I have the continuation in the Doctor's Autograph, which is exceedingly entertaining and curious, and full of anecdotes of his contemporaries. It is closely written in two 8vo. volumes, and comprises 554 pages, and appears to have been finally revised for publication. Why it never appeared I do not know. He was a very extraordinary and ingenious man, and wrote upon everything, from farriery to carving. With life in all its varieties he was perfectly acquainted, and had personally known almost every eminent man of his day. He had experienced every variety of fortune, but seems to have died in very reduced circumstances. The Sententiæ Variorum referred to by your correspondent is, I presume, what was published under the title of—

"Detached Philosophic Thoughts of near 300 of the best Writers, Ancient and Modern, on Man, Life, Death, and Immortality, systematically arranged under the Authors' Names." 2 vols. 12mo. 1810.

Jas. Crossley.Manchester, Jan. 25. 1851.

Miscellaneous

NOTES ON BOOKS, SALES, CATALOGUES, ETC

Dr. Latham seems to have adopted as his literary motto the dictum of the poet,

"The proper study of mankind is man."We have recently had occasion to call the attention of our readers to his learned and interesting volume entitled The English Language,—a work which affords proof how deeply he has studied that remarkable characteristic of our race, which Goldsmith wittily described as being "given to man to conceal his thoughts." From the language to The Natural History of the Varieties of Man, the transition is an easy one. The same preliminary studies lead to a mastery of both divisions of this one great subject: and having so lately seen how successfully Dr. Latham had pursued his researches into the languages of the earth, we were quite prepared to find, as we have done, the same learning, acumen, and philosophical spirit of investigation leading to the same satisfactory results in this kindred, but new field of inquiry. In paying a well-deserved tribute to his predecessor, Dr. Prichard, whom he describes as "a physiologist among physiologists, and a scholar among scholars,"—and his work as one "which, by combining the historical, the philological, and the anatomical methods, should command the attention of the naturalist, as well as of the scholar,"—Dr. Latham has at once done justice to that distinguished man, and expressed very neatly the opinion which will be entertained by the great majority of his readers of his own acquirements, and of the merits of this his last contribution to our stock of knowledge.

The Family Almanack and Educational Register for 1851, with what its editor justly describes as "its noble list of grammar schools," to a great extent the "offspring of the English Reformation in the sixteenth century," will be a very acceptable book to every parent who belongs to the middle classes of society; and who must feel that an endowed school, of which the masters are bound to produce testimonials of moral and intellectual fitness, presents the best security for the acquirement by his sons of a solid, well-grounded education.

Messrs. Sotheby and Wilkinson will sell on Monday next, and three following days, the valuable antiquarian, miscellaneous, and historical library of the late Mr. Amyot. The collection contains all the best works on English history, an important series of the valuable antiquarian publications of Tom Hearne; the first, second, and fourth editions of Shakspeare, and an extensive collection of Shakspeariana; and, in short, forms an admirably selected library of early English history and literature.

Catalogues Received.—Cole (15. Great Turnstile) List, No. XXXII. of very Cheap Books; W. Pedder (18. Holywell Street, Strand) Catalogue, Part I. for 1851, of Books Ancient and Modern; J. Wheldon (4. Paternoster Row) Catalogue of a Valuable Collection of Scientific Books; W. Brown (130. Old Street, London) Catalogue of English Books on Origin, Rise, Doctrines, Rites, Policy, &c., of the Church of Rome, &c., the Reformation, &c.

BOOKS AND ODD VOLUMES WANTED TO PURCHASE

Odd VolumesDrummond's History of Noble Families. Part II. containing Compton and Arden.

Bibliotheca Spenceriana, Vol. IV., and Bassano Collection.

Scott's Novels and Romances, last series, 14 vols., 8vo.—The Surgeon's Daughter.

*** Letters, stating particulars and lowest price, carriage free, to be sent to Mr. Bell, Publisher of "NOTES AND QUERIES," 186. Fleet Street.

Notices to Correspondents

Replies Received. Col. Hewson—True Blue—Plafery—Cockade—Warming Pans—Memoirs of Elizabeth—Paternoster Tackling—Forged Papal Bulls—By Hook or by Crook—Crossing Rivers on Skins—Fronte Capillatâ—Tandem D. O. M.—Cranmer's Descendants—Histoire des Severambes—Singing of Swans—Annoy—Queen Mary's Lament—Touching for the Evil—The Conquest—Scandal against Elizabeth—Shipster—Queries on Costume—Separation of Sexes in Church—Cum grano Salis—St. Paul's Clock—Sir John Davis—Aver.

H. J. Webb (Birmingham) has our best thanks for the Paper he so kindly sent.

Nemo. The book wanted is reported. Will he send his address to Mr. Bell?