Полная версия

Полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 55, November 16, 1850

"ADVERTISEMENT.

"To prevent the publicks being impos'd on, this is to give notice that the book lately published in 4to. is very imperfect and uncorrect, in so much that above thirty lines are omitted in several places, and many gross errors committed, which pervert the sense."

The above is in Italic type, and the body of the tract consists of only the first part of Absalom and Achitophel, as ordinarily printed: allowing for misprints (which are tolerably numerous), the poem stands very much the same as in several common editions I have at hand. My Query is, Is the work known to have been so published "for the benefit of the poor," and in order to give it greater circulation, and what is the explanation of the "Advertisement?"

THE HERMIT OF HOLYPORT.N.B. A short "Key" follows the usual address "To the Reader."

MINOR QUERIES

Edward the Confessor's Crucifix and Gold Chain.—In 1688 Ch. Taylour published A Narrative of the Finding St. Edward the King and Confessor's Crucifix and Gold Chain in the Abbey Church of St. Peter's, Westminster. Are the circumstances attending this discovery well known? And where now is the crucifix and chain?

EDWARD F. RIMBAULT.The Widow of the Wood.—Benjamin Victor published in 1755 a "narrative" entitled The Widow of the Wood. It is said to be very rare, having been "bought up" by the Wolseleys of Staffordshire. What is the history of the publication?

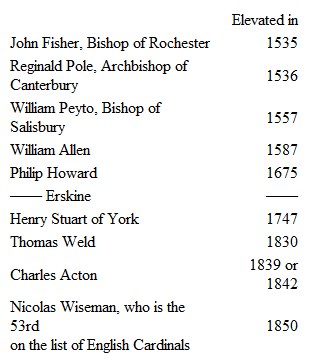

EDWARD F. RIMBAULT.Cardinal Erskine.—I am anxious to obtain some information respecting Cardinal Erskine, a Scotchman, as his name would impart, but called Cardinal of England? I suppose he was elevated to the sacred college between Cardinal Howard, the last mentioned by Dodd in his Church History, and the Cardinal of York, the last scion of the house of Stuart.

And is the following a correct list of English Cardinals since Wolsey, who died in 1530?

Both the latter were born abroad, the former at Naples, the latter at Seville; but they were born of British subjects, and were brought to England at an early age to be educated. The Cardinal of York was born in Rome; but being of the royal family of England, was always styled the Cardinal of England.

G.W.October 26. 1850.

Thomas Regiolapidensis.—Where can I find any information as to the saint who figures in the following curious story? Regiolapidensis may probably mean of Königstein, in Saxony; but Albon Butler takes no notice of this Thomas.

"Incipit narratiuncula e libro vingto, cui titular Vita atq. Gesta B. Thomæ Regiolapidensis, ex ordine FF. Prædicatorum, excerpta.

"Quum verò prædicator indefensus, missionum ecclesiasticarum causâ, in borealibus versaretur partibus, miraculum ibi stupendum sanè patravit. Conspexit enim taurum ingentem, vaccarum (sicut poëta quidam ex ethnicis ait) 'magnâ comitante catervâ,' in prato quodam graminoso ferocientem, maceriâ tantum bassâ inter se et belluam istam horrendam interpositâ. Constitit Thomas, constitit et bos, horribiliter rugiens, caudâ erectâ, cornibus immaniter sæviens, ore spumam, naribus vaporem, oculis fulgur emittens, maceriam transsilire, in virum sanctum irruere, corpusque ejus venerabile in aëra jactitare, visibiliter nimis paratus. Thomas autem, eaptâ occasione, oculos in monstrum obfirmat, signumque crucis magneticum in modum indesinenter ducere aggreditur, En portentum inauditum! geminis belluae luminibus illico palpebrae obducuntur, titubat taurus, cadit, ac, signo magnetico sopitus, primò raucum stertens, mox infantiliter placidum trahens halitum, humi pronus recumbit. Nec moratus donec hostis iste cornutus somnum excuteret, viv sanctus ad hospitium se propinquum laetus inde incolumisque recepit."

RUSTICUS."Her Brow was fair."—Can any of your many readers inform me of the author of the following lines, which I copy as I found them quoted in Dr. Armstrong's Lectures:

"Her brow was fair, but very pale,And looked like stainless marble; a touch methought would soilIts whiteness. On her temple, one blue veinRan like a tendril; one through her shadowy handBranched like the fibre of a leaf away."J.M.B.Hoods warn by Doctors of Divinity of Aberdeen.—Will you allow me to inquire, through the pages of your publication, of what colour and material the exterior and lining of hoods were composed which Doctors in Divinity, who had graduated at Aberdeen, Glasgow, and St. Andrew's, prior to the Reformation, were accustomed to wear? I imagine, the same as those worn by Doctors who had graduated at Paris: but what hoods they wore I know not. I trust that some of your correspondents will enlighten me upon this subject.

LL.D.Irish Brigade.—Where can I find any account of the institution and history of the Irish brigade, a part of the army of France under the Bourbons?

J.D.Bath.

Doctrine of the Immaculate Conception.—In the charge delivered by the Bishop of London to his clergy, on the 2nd instant, the following passage occurs:

"It is not easy to say what the members of that Church [the Church of Rome] are required to believe now; it is impossible for men to foresee what they may be called upon to admit as an article of faith next year, or in any future year: for instance, till of late it was open to a Roman Catholic to believe or not, as he might see reason, the fanciful notion of the immaculate conception of the Blessed Virgin; but the present Bishop of Rome has seen fit to make it an article of their faith; and no member of his church can henceforth question it without denying the infallibility of his spiritual sovereign, and so hazarding, as it is asserted, his own salvation."

Can any of your correspondents inform me where the papal decision on this point is to be found?

L.Gospel Oak Tree at Kentish Town.—Can you inform me why an ancient oak tree, in a field at Kentish Town, is called the "Gospel Oak Tree." It is situated and grows in the field called the "Gospel Oak Field," Kentish Town, St. Pancras, Middlesex. Tradition says Saint Augustine, or one of the ancient Fathers of the Church, preached under its branches.

STEPHEN.Arminian Nunnery in Huntingdonshire.—Where can I find an account of a religious academy called the Arminian Nunnery, founded by the family of the FERRARS, at Little Gidding in Huntingdonshire? I have seen some MS. collections of Francis Peck on the subject, but they are formed in a bad spirit. Has not Thomas Hearne left us something about this institution?

EDWARD F. RIMBAULT.Ruding's Annotated Langbaine.—Can any of your readers inform me who possesses the copy of Langbaine's Account of the English Dramatic Poets with MS. additions, and copious continuations, by the REV. ROGERS RUDING? In one of his notes, speaking of the Garrick collection of old plays, that industrious antiquary observes:

"This noble collection has lately (1784) been mutilated by tearing out such single plays as were duplicates to others in the Sloane Library. The folio editions of Shakespeare, Beaumont and Fletcher, and Jonson, have likewise been taken from it for the same reason."

This is a sad complaint against the Museum authorities of former times.

EDWARD F. RIMBAULT.Mrs. Tempest.—Can any of your correspondents give me any account of Mrs. (or, in our present style, Miss) Tempest, a young lady who died the day of the great storm in Nov., 1703, in honour of whom Pope's early friend Walshe wrote an elegiac pastoral, and invited Pope to give his "winter" pastoral "a turn to her memory." In the note on Pope's pastoral it is said that "she was of an ancient family in Yorkshire, and admired by Walshe." I have elsewhere read of her as "the celebrated Mrs. Tempest;" but I know of no other celebrity than that conferred by Walshe's pastoral; for Pope's has no special allusion to her.

C.Sitting cross-legged.—In an alliterative poem on Fortune (Reliquiæ Antiquæ, ii. p. 9.), written early in the fifteenth century, are the following lines:—

"Sitte, I say, and sethe on a semeli sete,Rygth on the rounde, on the rennyng ryng;Caste kne over kne, as a kynge kete,Comely clothed in a cope, crouned as a kyng."The third line seems to illustrate those early illuminations in which kings and great personages are represented as sitting cross-legged. There are numerous examples of the A.-S. period. Was it merely assumption of dignity, or was it not rather intended to ward off any evil influence which might affect the king whilst sitting, in his state? That this was a consideration of weight we learn from the passage in Bede, in which Ethelbert is described as receiving Augustine in the open air:

"Post dies ergo venit ad insulam rex, et residens sub divo jussit Augustinum cum sociis ad suum ibidem adveire colloquium; caverat enim ne in aliquam domum ad se introirent, vetere usus augurio, ne superventu suo, si quid maleficæ artis habuissent, eum superando deciperent."—Hist. Eccles., l. i. c. 25.

It was cross-legged that Lucina was sitting before the floor of Alemena when she was deceived by Galanthes. In Devonshire there is still a saying which recommends "sitting cross-legged to help persons on a journey;" and it is employed as a charm by schoolboys in order to avert punishment. (Ellis's Brand, iii. 258.) Were not the cross-legged effigies, formerly considered to be those of Crusaders, so arranged with an idea of the mysterious virtue of the position?

RICHARD J. KING.Twickenham—Did Elizabeth visit Bacon there?—I believe all the authors who within the last sixty years have written on the history of Twickenham, Middlesex (and among the most known of these I may mention Lysons, Ironside, and John Norris Brewer), have, when mentioning Twickenham Park, formerly the seat of Lord Bacon, stated that he there entertained Queen Elizabeth. Of this circumstance I find no account in the works of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. His lordship entertained her at Gorhambury in one of her progresses; and I would ask if it be possible that Twickenham may have been mistaken for his other seat of Gorhambury? It is well known Queen Elizabeth passed much of the latter part of her life at Richmond, and ended her days there; and in Mr. Nares' Memoirs of Lord Burghley there is an account of her visit to Barn-Elms; and there is also a curious description of her visit to Kew (in that neighbourhood) in the Sydney Papers, published by Arthur Collins, in two vols. folio, vol. i. p. 376., in a letter from Rowland Whyte, Esq. Had Lord Bacon received her majesty, it must most probably have been in 1595. But perhaps some of your readers may be able to supply me with information on this subject.

D.N.Burial towards the West.—The usual posture of the dead is with the feet eastward, and the head towards the west: the fitting attitude of men who look for their Lord, "whose name is The East," and who will come to judgement in the regions of the dawn suddenly. But it was the ancient usage of the Church that the martyr, the bishop, the saint, and even the priest, should occupy in their sepulture a position the reverse of the secular dead, and lie down with their feet westward, and their heads to the rising sun. The position of the crozier and the cross on ancient sepulchres of the clergy record and reveal this fact. The doctrine suggested by such a burial was, that these mighty men which were of old would be honoured with a first resurrection, and as their Master came on from the east, they were to arise and to follow the Lamb as He went; insomuch that they, with Him, would advance to the Judgement of the general multitudes,—the ancients and the saints which were worthy to judge and reign. Now, Sir, my purpose in this statement is to elicit, if I may, from your learned readers illustrations of this distinctive interment.

R.S. HAWKER.Morwenstow.

Medal struck by Charles II.—Voltaire, in his Histoire de Charles XII., liv. 4., states that a medal was struck in commemoration of a victory which Charles XII. gained over the Russians, at a place named Hollosin, near the Boresthenes, in the year 1708. He adds that on one side of this medal was the epigraph, "Sylvæ, paludes, aggeres, hostes victi;" on the other the verse of Lucan:—

"Victrices copias alium laturus in orbem."The verse of Lucan referred to is in lib. v. l.238.:

"Victrices aquilas alium laturus in orbem."Query, Is the medal referred to by Voltaire known to exist? and if so, is the substitution of the unmetrical and prosaic word copias due to the author of the medal, or to Voltaire himself?

L.National Debt.—What volumes, pamphlets, or paragraphs can be pointed out to the writer, in poetry or prose, alluding to the bribery, corruption, and abuses connected with the formation of the National Debt from 1698 to 1815?

F.H.B.Midwives licensed.—In the articles to be inquired into in the province of Canterbury, anno 1571 (Grindal Rem., Park. Soc. 174-58), inquiry to be made

"Whether any use charms, or unlawful prayers, or invocations, in Latin or otherwise, and namely, midwives in the time of women's travail of child."

In the oath taken by Eleanor Pead before being licensed by the Archbishop to be a midwife a similar clause occurs; the words, "Also, I will not use any kind of sorcery or incantations in the time of the travail of any woman." Can any of your readers inform me what charms or prayers are here referred to, and at what period midwives ceased to be licensed by the Archbishop, or if any traces of such license are still found in Roman Catholic countries?

S.P.H.T.REPLIES

THE BLACK ROOD OF SCOTLAND

(Vol. ii., p. 308.)I am not aware of any record in which mention of this relique occurs before the time of St. Margaret. It seems very probable that the venerated crucifix which was so termed was one of the treasures which descended with the crown of the Anglo-Saxon kings. When the princess Margaret, with her brother Edgar, the lawful heir to the throne of St. Edward the Confessor, fled into Scotland, after the victory of William, she carried this cross with her amongst her other treasures. Aelred of Rievaulx (ap. Twysd. 350.) gives a reason why it was so highly valued, and some description of the rood itself:

"Est autem crux illa longitudinem habens palmæ de auro purissimo mirabili opere fabricats, quæ in modum techæ clauditur et aperitur. Cernitur in ea quædarn Dominicæ crucis portio, (sicut sæpe multorum miraculorum argumento probatum est). Salvatoris nostri ymaginem habens de ebore densissime sculptam et aureis distinctionibus mirabiliter decoratam."

St. Margaret appears to have destined it for the abbey which she and her royal husband, Malcolm III., founded at Dunfermline in honour of the Holy Trinity: and this cross seems to have engaged her last thoughts for her confessor relates that, when dying, she caused it to be brought to her, and that she embraced, and gazed steadfastly upon it, until her soul passed from time to eternity. Upon her death (16th Nov., 1093), the Black Rood was deposited upon the altar of Dunfermline Abbey, where St. Margaret was interred.

The next mention of it that I have been enabled to make note of, occurs in 1292, in the Catalogue of Scottish Muniments which were received within the Castle of Edinburgh, in the presence of the Abbots of Dunfermline and Holy Rood, and the Commissioners of Edward I., on the 23rd August in that year, and were conveyed to Berwick-upon-Tweed. Under the head

"Omnia ista inventa fuerunt in quadam cista in Dormitorio S. Crucis, et ibidem reposita prædictos Abbates et altos, sub ecrum sigillis."

we find

"Unum scrinium argenteum deauratum, in quo reponitur crux quo vocatur la blake rode."—Robertson's Index, Introd. xiii.

It does not appear that any such fatality was ascribed to this relique as that which the Scots attributed to the possession of the famous stone on which their kings were crowned, or it might be conjectured that when Edward I. brought "the fatal seat" from Scone to Westminster, he brought the Black Rood of Scotland too. That amiable and pleasing historian, Miss Strickland, has stated that the English viewed the possession of this relique by the Scottish kings with jealousy; that it was seized upon by Edward I., but restored on the treaty of peace in 1327. This statement is erroneous; the rood having been mistaken for the stone, which, by the way, as your readers know, was never restored.

We next find it in the possession of King David Bruce, who lost this treasured relique, with his own liberty, at the battle of Durham (18th Oct., 1346), and from that time the monks of Durham became its possessors. In the Description of the Ancient Monuments, Rites, and Customs of the Abbey Church of Durham, as they existed at the dissolution, which was written in 1593, and was published by Davies in 1672, and subsequently by the Surtees Society, we find it described as

"A most faire roode or picture of our Saviour, in silver, called the Black Roode of Scotland, brought out of Holy Rood House, by King David Bruce … with the picture of Our Lady on the one side of our Saviour, and St. John's on the other side, very richly wrought in silver, all three having crownes of pure beaten gold of goldsmith's work, with a device or rest to take them off or on."

The writer then describes the "fine wainscote work" to which this costly "rood and pictures" were fastened on a pillar at the east end of the southern aisle of the quire. And in a subsequent chapter (p. 21. of Surtees Soc. volume) we have an account of the cross miraculously received by David I. (whom the writer confounds with the King David Bruce captured at the battle of Durham, notwithstanding that his Auntient Memorial professes to be "collected forthe of the best antiquaries"), and in honour of which he founded Holy Rood Abbey in 1128 from which account it clearly appears that this cross was distinct from the Black Rood of Scotland. For the writer, after stating that this miraculous cross had been brought from Holy Rood House by the king, as a "most fortunate relique," says:

"He lost the said crosse, which was taiken upon him, and many other most wourthie and excellent jewells … which all weare offred up at the shryne of Saint Cuthbert, together with the Blacke Rude of Scotland (so termed), with Mary and John, maid of silver, being, as yt were, smoked all over, which was placed and sett up most exactlie in the pillar next St. Cuthbert's shrine," &c.

In the description written in 1593, as printed, the size of the Black Rood is not mentioned; but in Sanderson's Antiquities of Durham, in which he follows that description, but with many variations and omissions, he says (p. 22.), in mentioning the Black Rood of Scotland, with the images, as above described,—

"Which rood and pictures were all three very richly wrought in silver, and were all smoked blacke over, being large pictures of a yard or five quarters long, and on every one of their leads a crown of pure beaten gold," &c.

I have one more (too brief) notice of this famous rood. It occurs in the list of reliques preserved in the Feretory of St. Cuthhert, under the care of the shrine-keeper, which was drawn up in 1383 by Richard de Sedbrok, and is as follows:

"A black crosse, called the Black Rode of Scotland."—MS. Dunelm., B. ii. 35.

Strange to say, Mr. Raine, in his St. Cuthbert, p. 108., appears to confound the cross brought from Holy Rood House, and in honour of which it was founded, with the Black Rood of Scotland. He was misled, no doubt, by the statement in the passage above extracted from the Ancient Monuments, that this cross was brought out of Holy Rood House.

I fear that the fact that it was formed of silver and gold, gives little reason to hope that this historical relique escaped destruction when it came into the hands of King Henry's church robbers. Its sanctity may, indeed, have induced the monks to send it with some other reliques to a place of refuge on the Continent, until the tyranny should be overpast; but there is not any tradition at Durham, that I am aware of, to throw light on the concluding Query of your correspondent P.A.F., as to "what became of the 'Holy Cross,' or 'Black Rood,' at the dissolution of Durham Priory?"

That the Black Rood of Scotland, and the Cross of Holy Rood House were distinct, there can, I think, be no doubt. The cross mentioned by Aelred is not mentioned as the "Black Rood:" probably it acquired this designation after his time. But Fordoun, in the Scoti-Chronicon, Lord Hailes in his Annals, and other historians, have taken Aelred's account as referring to the Black Rood of Scotland. Whether it had been brought from Dunfermline to Edinburgh before Edward's campaign, and remained thenceforth deposited in Holy Rood Abbey, does not appear: but it is probable that a relique to which the sovereigns of Scotland attached so much veneration was kept at the latter place.

W.S.G.Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Nov. 2. 1850.

REPLIES TO MINOR QUERIES

Hæmony (Vol. ii., p. 88.).—MR. BASHAM will find some account of this plant under the slightly different type of "Hēmionion" in Pliny, xxv. 20., xvi. 25., xxvii. 17.:

"Invenit et Teucer eadem ætate Teucrion, quam quidam 'Hemionion' vocant, spargentem juncos tenues, folia parva, asperis locis nascentem, austero sapore, nunquam florentem: neque semen gignit. Medetur lienibus … Narrantque sues qui radicem ejus ederint sine splene inveniri.

"Singultus hemionium sedat.

"'Asplenon' sunt qui hemionion vocant foliis trientalibus multis, radice limosa, cavernosa, sicut filicis, candida, hirsuta: nec caulem, nec florem, nec semen habet. Nascitur in petris parietibusque opacis, humidis."

According to Hardouin's note, p. 3777., it is the Ceterach of the shops, or rather Citrach; a great favourite of the mules, ‛ημιονοι, witness Theophrastus, Hist., ix. 19.

Ray found it "on the walls about Bristol, and the stones at St. Vincent's rock." He calls it "Spleenwort" and "Miltwaste." Catalog. Plant. p. 31. Lond. 1677.

I have a copy of Henri du Puy's "original" Comus, but do not recollect his noticing the plant.

G.M.Guernsey.

Byron's Birthplace.—Can any of your correspondents give any information relative to the house in which Lord Byron was born? His biographers state that it was in Holles Street, but do not mention the number.

C.B.W.Edgbaston.

[Our correspondent will find, on referring to Mr. Cunningham's Handbook of London, that "Byron was born at No. 24. Holles Street, and christened in the small parish church of St. Marylebone."]

Ancient Tiles (Vol. i., p. 173.).—The device of two birds perched back to back on the twigs of a branch that rises between them, is found, not on tiles only, but in wood carving; as at Exeter Cathedral, on two of the Misereres in the choir, and on the gates which separate the choir from the aisles, and these again from the nave.

J.W.H.Modena Family (Vol. ii., p. 266.).—Victor Amadeus III., King of Sardinia, died in October, 1796. Mary Beatrice, Duchess of Modena, mother of the present Duke of Modena, was the daughter of Victor Emmanuel V., King of Sardinia, who abdicated his throne in 1821, and died 10th January, 1824. The present Duke of Modena is the direct heir of the house of Stuart in the following line:—

All the legitimate issue of Charles II. and James II. being extinct, we fall back upon Henrietta Maria, youngest child of Charles I. She married her cousin Philip, Duke of Orleans, brother of Louis XIV., and by him had three children. Two died without issue: the youngest, Anna Maria, b. Aug. 1669, mar. Victor Amadeus II., Duke of Savoy, and had by him three children, one son and two daughters.

The son, Charles Emmanuel III., Duke of Savoy, married and had Victor Amadeus III., who married Maria Antoinette of Spain, and had:—1. Charles Emmanuel IV., who died without issue, and 2. Victor Emmanuel V., who married an Austrian Archduchess; his eldest daughter married Francis IV. Duke of Modena. She died between A.D. 1841-1846, I believe, and left four children:—1. Francis V., Duke of Modena. 2. The wife of Henri, Comte de Chambord. 3. Ferdinand. 4. Marie, wife of Don Juan, brother of the present de jure King of Spain, Carlos VI.