Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Notes and Queries, Number 31, June 1, 1850

I procured this volume from the collection of Mr. Heber, vii. 1682.—Sir William Musgrave was a Trustee of the British Museum, and bequeathed near two thousand volumes to that incomparable establishment. He was partial to biography, and gave much assistance to Granger. His Adversaria and Obituary, I often consult. The latter work is an excellent specimen of well-applied assiduity. Ob. 1800.

BOLTON CORNEY.Queries

PUNISHMENT OF DEATH BY BURNING

Judging from the astonishment with which I learned from an eye-witness the circumstance, I think that some of your readers will be surprised to learn that, within the memory of witnesses still alive, a woman was burnt to death under sentence of the judge of assize, for the murder of her husband.

This crime—petty treason—was formerly punished with fire and faggot; and the repeal of the law is mentioned by Lord Campbell in a note to his life of one of our recent chancellors, but I have not his work to refer to.

The post to which this woman was bound stood, till recently, in a field adjoining Winchester.

She was condemned to be burnt at the stake; and a marine, her paramour and an accomplice in the murder, was condemned to be hanged.

A gentleman lately deceased told me the circumstances minutely. I think that he had been at the trial, but I know that he was at the execution, and saw the wretched woman fixed to the stake, fire put to the faggots, and her body burnt. But I know two persons still alive who were present at her execution, and I endeavoured, in 1848, to ascertain from one of them the date of this event, and "made a note" of his answer, which was to this effect:—

"I can't recollect the year; but I remember the circumstance well. It was about sixty-five years ago. I was there alone with the crowd. I sat on my father's shoulder, and saw them bring her and the marine to the field. They fixed her neck by a rope to the stake, and then set fire to the faggots, and burnt her."

She was probably strangled by this rope.

One Query which I would ask is, Was this execution at Winchester, in 1783 (or thereabouts), the last instance in England? and another is, Are you aware of any other instance in the latter part of the last century?

E.S.S.W.CORNELIS DREBBEL

In a very curious little book, entitled Kronÿcke van Alemaer, and published in that town anno 1645, I read the following particulars about Cornelis Drebbel, a native of the same city.

Being justly renowned as a natural philosopher, and having made great progress in mechanics, our Drebbel was named tutor of the young Prince of Austria, by the emperor Ferdinandus II.; an office which he fulfilled so well, that he was afterwards chosen councillor to his Majesty, and honoured with a rich pension for past services. But, alas! in the year 1620, Prague, the place he dwelt in, was taken by Frederick, then king of Bohemia, several members of the imperial council were imprisoned, and some of them even put to death.

Bereft of every thing he possessed, a prisoner as well as the others, poor Drebbel would perhaps have undergone the same lot if the High Mighty States of the United Provinces had not sent a message to the King of England, asking him to interfere in their countryman's favour. They succeeded in their benevolent request for his English Majesty obtained at last from his son-in-law, the Dutch philosopher's liberation, who (I don't exaggerate) was made a present of to the British king; maybe as a sort of lion, which the king of Morocco had never yet thought of bestowing upon the monarch as a regal offering.

Drebbel, however, did not forget how much he owed to the intercession of King James, and, to show his gratitude, presented him with an object of very peculiar make. I will try to give you an exact version of its not very clear description in the Dutch book.

"A glass or crystal globe, wherein he blew or made a perpetual motion by the power of the four elements. For every thing which (by the force of the elements) passes, in a year, on the surface of the earth (sic!) could be seen to pass in this cylindrical wonder in the shorter lapse of twenty-four hours. Thus were marked by it, all years, months, days, hours; the course of the sun, moon, planets, and stars, &c. It made you understand what cold is, what the cause of the primum mobile, what the first principle of the sun, how it moves the firmament, all stars, the moon, the sea, the surface of the earth, what occasions the ebb, flood, thunder, lightning, rain, wind, and how all things wax and multiply, &c.,—as every one can be informed of by Drebbel's own works; we refer the curious to his book, entitled Eeuwige Beweginghe (Perpetual Motion)."

Can this instrument have been a kind of Orrery?

"He built a ship, in which one could row and navigate under water, from Westminster to Greenwich, the distance of two Dutch miles; even five or six miles, as far as one pleased. In this boat, a person could see under the surface of the water, and without candlelight, as much as he needed to read in the Bible or any other book. Not long ago, this remarkable ship was yet to be seen lying on the Thames or London river.

"Aided by some instruments of his own manufacture, Drebbel could make it rain, lighten, and thunder at every time of the year, so that you would have sworn it came in a natural way from heaven.

"By means of other instruments, he could, in the midst of summer, so much refrigerate the atmosphere of certain places, that you would have thought yourself in the very midst of winter. This experiment he did once on his Majesty's request, in the great Hall of Westminster; and although a hot summer day had been chosen by the King, it became so cold in the Hall, that James and his followers took to their heels in hasty flight.

"With a certain instrument, he could draw an incredible quantity of water out of a well or river.

"By his peculiar ingenuity, he could, at all times of the year, even in the midst of winter, hatch chickens and ducklings without using hens or ducks.

"He made instruments, by means of which were seen pictures and portraits; for instance, he could show you kings, princes, nobles, although residing at that moment in foreign countries. And there was no paint nor painter's work to be seen, so that you saw a picture in appearance, but not in reality."

Perhaps a magic lantern?

"He could make a glass, that placed in the dark near him or another, drew the light of a candle, standing at the other end of a long room, with such force, that the glass near him reflected so much light as to enable him to see to read perfectly."

Was this done by parallel parabolical mirrors?

"He could make a plane glass without grinding it on either side, in which people saw themselves reflected seven times.

"He invented all these and many other curiosities, too long to relate, without the aid of the black art; but by natural philosophy alone, if we may believe the tongues whose eyes saw it. By these experiments, he so gained the King's favour, his Majesty granted him a pension of 2000 guilders. He died in London, anno 1634, the sixtieth year of his age."

Thus writes the Alkmaar chronicler. If you, or any of your learned correspondents, can elucidate the history of the instruments made by my countryman, he will much oblige all scientific antiquarians, and me, though not a Dr. Heavybottom, especially. I need not make apologies for my bad English, and hope none of your many readers will criticise it in a Dutch periodical.

JANUS DOUSA.Amsterdam, April, 1850.

VERSES ATTRIBUTED TO CHARLES YORKE

I have in my possession a MS. book, in his own handwriting, of the late Rev. MARTIN STAFFORD SMITH of Bath, formerly chaplain to BISHOP WARBURTON, containing, amongst other matter, a series of letters, and extracts of letters, from the amiable and gifted, but unfortunate, CHARLES YORKE, to Bishop Warburton. At the close of this series, is the following note and extract:—

"Verses transcribed from the original, in Mr. C. Yorke's own writing, among his letters to Bishop Warburton; probably manuscript, and certainly his own composition: written from the Shades."

"Stript to the naked soul, escaped from clay,From doubts unfetter'd, and dissolv'd in day,Unwarm'd by vanity, unreach'd by strife,And all my hopes and fears thrown off with life,—Why am I charm'd by Friendship's fond essays,And, tho' unbodied, conscious of thy praise?Has pride a portion in the parted soul?Does passion still the formless mind controul?Can gratitude out-pant the silent breath,Or a friend's sorrow pierce the glooms of death?No; 'tis a spirit's nobler taste of bliss,That feels the worth it left, in proofs like this;That not its own applause but thine approves,Whose practice praises, and whose virtue loves;Who lov'st to crown departed friends with fame,Then dying late, shalt all thou gav'st reclaim."It is my own impression, as well as that of an eminent critic to whom I communicated these lines, that they have been printed. If any contributor to "NOTES AND QUERIES" can tell where they are to be found, or can throw any light on their authorship, it will gratify

THE EDITOR OF BP. WARBURTON'SLITERARY REMAINS.Bath, May 18. 1850.

CULTIVATION OF GEOMETRY IN LANCASHIRE

It has been a frequent subject of remark, that geometry in its purest form has been cultivated in the northern counties, but more especially in Lancashire, with extraordinary ardour and success; and this by a class of men placed in a position the most unpropitious that can be conceived for the study—by operatives of the humblest class, and these chiefly weavers. The geometrical labours of these men would have gladdened the hearts of Euclid, Apollonius and Archimedes, and would have been chronicled by Pappus with his usual truthfulness and judicious commendation; had they only but so laboured in Greece, antecedently to, or cotemporarily with, those "fathers of geometry," instead of in modern England, cotemporarily with the Hargreaves, the Peels, and the Arkwrights. Yet not one in a thousand of your readers, perhaps, has ever heard of these men; and the visible traces of their existence and labours are very few, scarce, and scattered. A vague general statement respecting the prevalence of geometrical studies amongst the "middle-classes" of England was made by Playfair in the Edinburgh Review many years ago, which is quite calculated to mislead the reader; and the subject was dwelt upon at some length, and eloquently, by Harvey, at the British Association in 1831. Attention has been more recently directed to this subject by two living geometers—one in the Philosophical Magazine, and the other in the Mechanics'; but they both have wholly untouched a question of primary importance—even almost unmentioned:—it is, how, when, where, and by whom, was this most unlikely direction given to the minds of these men?

An answer to this question would form an important chapter in the history of human development, and throw much light upon the great educational questions of the present day. It may furnish useful hints for legislation, and would be of singular aid to those who were appointed to work out legislative objects in a true spirit. It cannot be doubted that a succinct account of the origin of this taste, and of the influences by which it has been maintained even to the present hour, would be a subject of interest to most of your readers, quite irrespective the greater or less importance and difficulty of the studies themselves, as the result would show how knowledge cannot only be effectively diffused but successfully extended under circumstances apparently the most hopeless.

Nor does Manchester stand as the only instance, for the weavers of Spitalfields display precisely the same singular phenomenon. What is still more singular is, that the same class in both localities have shown the same ardent devotion to natural history, and especially to Botany; although it is to be remarked that, whilst the botanists of Spitalfields have been horticulturists, those of Manchester have confined themselves more to English field flowers, the far more worthy and intellectual of the two.

We could add a "Note" here and there on some points arising out of this question; but our want of definite and complete information, and of the means of gaining it (except through you), compels us to leave the subject to others, better qualified for its discussion. Pray, sir, open your pages to the question, and oblige, your ever obedient servants,

PEN-AND-INK.Hill Top, May 27, 1850.

ASINORUM SEPULTURA

In former times it was the practice, upon the demise of those who died under sentence of excommunication, not merely to refuse interment to their bodies in consecrated ground, but to decline giving them any species of interment at all. The corpse was placed upon the surface of the earth, and there surrounded and covered over with stones. It was blocked up, "imblocatus," and this mode of disposing of dead bodies was designated "Asinorum Sepultura." Ducange gives more than one instance, viz., "Sepultura asini sepeliantur"—"ejusque corpus exanime asinorum accipiat sepulturam."

Wherefore was this mode of disposing of the dead bodies called "an ass's sepulture?" It is not sufficient to say that the body of a human being was buried like that of a beast, for then the term would be general and not particular; neither can I imagine that Christian writers used the phrase for the purpose of repudiating the accusation preferred against them by Pagans, of worshipping an ass. (See Baronius, ad. an. 201. §21.) The dead carcasses of dogs and hounds were sometimes attached to the bodies of criminals. (See Grinds, Deutsche Rechte Alterthum, pp. 685, 686.) I refer to this to show that there must have been some special reason for the term "asinorum sepultura". That reason I would wish to have explained; Ducange does not give it, he merely tells what was the practice; and the attention of Grimm, it is plain, from his explanation of the "unehrliches begräbnis" (pp. 726, 727, 728.), was not directed towards it.

W.B. MACCABE.Minor Queries

Ransom of an English Nobleman.—At page 28. vol. ii. of the Secret History of the Court of James I., Edinburgh, 1811 (a reprint), occurs the following:—

"Nay, to how lowe an ebbe of honor was this our poore despicable kingdome brought, that (even in Queen Elizabeth's time, the glory of the world) a great nobleman being taken prisoner, was freely released with this farewell given him, that they desired but two mastieffes for his ransome!"

Who was this great nobleman, and where may I find the fullest particulars of the whole transaction?

H.C.When does Easter end?—An enactment of the legislature directs a certain act to be done "within two months after Easter" in 1850, under a penalty for non-performance. I have no difficulty in finding that two calendar months are meant, but am puzzled how to compute when they should commence. I should be much obliged by being informed when Easter ends? that question set at rest, the other part is easily understood and obeyed.

H. EDWARDS.Carucate of Land.—Will any one inform me what were the dimensions of a carucate of land, in Edward III.'s time? also, what was the comparative value of money at the same date? Are Tables, giving the value of money at various periods in our history, to be found in any readily accessible source?

E.V.Members for Calais.—Henry VIII. granted a representative in the English parliament to the town of Calais. Can any of your correspondents inform me whether this right was exercised till the loss of that town, and, if so, who were the members?

O.P.Q.Members for Durham.—What was the reason that neither the county nor the city of Durham returned members to parliament previous to 1673-4?

O.P.Q.Leicester, and the reputed Poisoners of his Time.—At page 315. vol. ii. of D'Israeli's Amenities of Literature, London, 1840, is as follows:—

"We find strange persons in the Earl's household (Leicester). Salvador, the Italian chemist, a confidential counsellor, supposed to have departed from this world with many secrets, succeeded by Dr. Julio, who risked the promotion. We are told of the lady who had lost her hair and her nails," … "of the Cardinal Chatillon, who, after being closeted with the Queen, returning to France, never got beyond Canterbury; of the sending a casuist with a case of conscience to Walsingham, to satisfy that statesman of the moral expediency of ridding the state of the Queen of Scots by an Italian philtre."

Where may I turn for the above, more particularly for an account of the lady who had lost her hair and her nails?

H.C.April 9. 1850.

Lord John Townshend's Poetical Works.—Can any of your readers inform me whether the poetical works of Lord John Townshend, M.P., were ever collected and published, and, if so, when, and by whom? His lordship, who, it will be remembered, successively represented Cambridge University, Westminster, and Knaresborough, was considered to be the principal contributor to the Rolliad, and the author of many odes, sonnets, and other political effusions which circulated during, the eventful period 1780-1810.

OXONIENSIS.May 4.

Martello Towers.—Is it the fact that the towers erected along the low coasts of Kent and Sussex during the prevalent dread of the French invasion received their designation from a town in Spain, where they were first built? By whom was the plan introduced into England? Is any account of their erection to be found in any Blue Book of the period?

E.V."Sachent tous que Mons. Gualhard de Dureffourt … ad recue … quatorze guianois dour et dys sondz de la mon[oye] currant a Burdeux."

The date is 12. Nov. 1387. The document is quoted in Madox's Baronia Anglica, p. 159. note d.

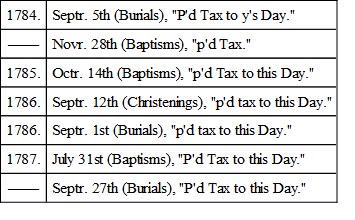

A.J.H.Parish Registers Tax.—In the Parish Register of Wigston Magna, Leicestershire, are the following entries against several dates in the Baptisms and Burials:—

I should be glad to be informed what tax is here referred to. These are all the entries of the kind.

ARUN."The following piece of mysticism has been sent to us as original, with a request for a solution. The authorship is among the secrets of literature: it is said to have been by Fox, Sheridan, Gregory, Psalmenazar, Lord Byron, and the Wandering Jew. We leave the question to our erudite readers."

"I sit on a rockWhile I'm raising the wind,But the storm once abated,I'm gentle and kind;I see kings at my feet,Who wait but my nod,To kneel in the dustWhich my footsteps have trod.Though seen by the world,I'm known but to few;The Gentiles detest me,I'm pork to the Jew.I never have pastBut one night in the dark,And that was with Noah,Alone, in the ark.My weight is three pounds,My length is a mile,And when I'm discover'd,You'll say, with a smile,My first and my lastAre the wish of our isle."I should be obliged if any body could give me a key to this.

QUAESTOR.

Replies

HOWKEY OR HORKEY

Howkey or Horkey (Vol. i. p. 263.) is evidently, as your East Anglian correspondent and J.M.B. have pointed out, a corrupt pronunciation of the original Hockey; Hock being a heap of sheaves of corn, and hence the hock-cart, or cart loaded with sheaves.

Herrick, who often affords pleasing illustrations of old rural customs and superstitions, has a short poem, addressed to Lord Westmoreland, entitled "The Hock-cart, or Harvest Home," in which he says:—

"The harvest swains and wenches bound,For joy to see the hock-cart crown'd."Die Hocke was, in the language of Lower Saxony, a heap of sheaves. Hocken was the act of piling up these sheaves; and in that valuable repertory of old and provincial German words, the Wörterbuch of J.L. Frisch, it is shown to belong to the family of words which signify a heap or hilly protuberance.

We should have been prepared to find the word in East Anglia; but from Herrick's use of it, and others, it must have formerly been prevalent in the West of England also. It has nothing to do with Hock-tide, which is the Hoch-zeit of the Germans, and is merely [Transcriber's note: illegible] feast or highday of which a very satisfactory account will be found in Mr. Hampson's "Glossary" annexed to his Medii Aevi Kalendarium. An interesting account of the Hoch-zeit of the Germans of Lower Saxony occurs where we should little expect it, in the Sprichwörter of Master Egenolf, printed at Francfort in 1548, 4to.; and may perhaps serve to illustrate some of our obsolete rural customs:—

"We Germans keep carnival (all the time between Epiphany and Ash-Wednesday) St. Bernard's and St. Martin's days, Whitsuntide and Easter, as times, above all other periods of the year, when we should eat, drink, and be merry. St. Burchard's day, on account of the fermentation of the new must. St. Martin's, probably on account of the fermentation of the new wine: then we roast fat geese, and all the world enjoy themselves. At Easter we bake pancakes (fladen); at Whitsuntide we make bowers of green boughs, and keep the feast of the tabernacle in Saxony and Thuringia; and we drink, Whitsun-beer for eight days. In Saxony, we also keep the feast of St. Panthalion with drinking and eating sausages and roast legs of mutton stuffed with garlic. To the kirmse, or church feast, which happens only once a year, four or five neighbouring villages go together, and it is a praiseworthy custom, as it maintains a neighbourly and kindly feeling among the people."

The pleasing account of the English harvest feast in Gage's Hengrave, calls it Hochay. Pegge, in his Supplement to Grose's Provincial Words, Hockey. Dr. Nares notices it in his Glossary, and refers to an account of its observance in Suffolk given in the New Monthly Magazine for November, 1820. See also Major Moor's Suffolk Words, and Forby's Vocabulary of East Anglia, who says that Bloomfield, the rustic poet of Suffolk, calls it the Horky; Dr. Nares having said that Bloomfield does not venture on this provincial term for a Harvest-home.

S.W. SINGER.May 14. 1850.

CHARLES MARTEL

(Vol. i. pp. 86. 275.)

If Charles Martel must no longer be the Mauler, he will only be excluded from a very motley band. Here are a few of his repudiated namesakes:—

1. The Maccabæi from Hebr. Makkab, a hammer.

2. Edward I., "Malleus Scotorum."

3. "St. Augustine, that Maul of heretics, was in chief repute with" Josias Shute, among the Latin Fathers. (Lloyd's Memoires, p. 294.) "God make you as Augustine, Malleum Hæreticorum." (Edward's Gangraena, Part II. p. 17. 1646.)

4. "Robertus Grossetest, Episcopus Lincolniensis, Romanorum Malleus, ob. 1253." (Fulman, Notitia Oxon. p. 103. 2nd ed.)

5. "Petrus de Alliaco, circ. A.D. 1400, Malleus a veritate aberrantium indefessus appellari solebat." (Wharton in Keble's Hooker, i. 102.)

6. T. Cromwell, "Malleus Monachorum:" "Mauler of Monasteries" [Fuller, if I recollect rightly, quoted by Carlyle]. Also, "Mawling religious houses." (Lloyd's State Worthies, i. 72. 8vo. ed.)

"FEAST" AND "FAST."

I am not going to take part in the game of hockey, started by LORD BRAYBROOKE, and carried on with so much spirit by several of your correspondents in No. 28.; but I have a word to say to one of the hockey-players, C.B., who, per fas et nefas, has mixed up "feast and fast" with the game.

C.B. asks, "Is not the derivation of 'feast' and 'fast' originally the same? that which is appointed connected with 'fas,' and that from 'fari?'" I should say no; and let me cite the familiar lines from the beginning of Ovid's Fasti:—