Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Notes and Queries, Number 179, April 2, 1853.

Without specially binding myself to either one of these conflicting testimonies, I may be allowed to suggest that, apart from any proof to the contrary, the inference that he was a native of Chester is a perfectly fair and legitimate one. His Short Treatise of the Isle of Man, which was the only work he ever sent to press, was printed at the end of that famous Cheshire work, the Vale Royal of England, in 1656, and was illustrated with engravings by Daniel King, the editor of that work, himself a Cheshire man. Independent of this, his biographer Wood informs us that he was "a singular lover of antiquities," and that he "made collections of arms, monuments, &c., in Staffordshire, Salop, and Chester," the which collections are now, I believe, in the British Museum. He made no collections for Yorkshire, nor yet for London, where he is stated by Wood to have been born. One thing is certain, James Chaloner of Chester was living at the time this treatise was written, and was, moreover, a famous antiquary, and a collector for this, his native county; but whether he was, de facto, the regicide, or merely his cotemporary, I leave it to older and wiser heads to determine.

T. Hughes.Chester.

*[In the Harleian Collection, No. 1927., will be found "A paper Book in 8vo., wherein are contained, Poems, Impreses, and other Collections in Prose and Verse; written by Thomas Chaloner and Randle Holme, senior, both Armes-Painters in Chester, with other Notes of less value."—Ed.]

"ANYWHEN" AND "SELDOM-WHEN:" UNOBSERVED INSTANCES OF SHAKSPEARE'S USE OF THE LATTER

(Vol. vii., p. 38.)Mr. Fraser's remark about the word anywhen has brought to my mind two passages in Shakspeare which have been always hitherto rendered obscure by wrong printing and wrong pointing. The first occurs in Measure for Measure, Act IV. Sc. 2., where the Duke says:

"This is a gentle provost: seldom-whenThe steeled gaoler is the friend of men."Here the compound word, signifying rarely, not often, has been always printed as two words; and Mr. Collier, following others, has even placed a comma between seldom and when.

The other passage occurs in the Second Part of King Henry IV., Act IV. Sc. 4.; where Worcester endeavours to persuade the king that Prince Henry will leave his wild courses. King Henry replies:

"'Tis seldom-when the bee doth leave her combIn the dead carrion."Here also the editors have always printed it as two words; and, as before, Mr. Collier here repeats the comma.

That the word was current with our ancestors, is certain; and I have no doubt that other instances of it may be found. We have a similar compound in Chaucer's Knight's Tale, v. 7958.:

"I me rejoyced of my lyberté,That selden-tyme is founde in mariage."Palsgrave, too, in his Eclaircissement de la Langue Françoise, 1530, has—

"Seldom-what, Gueres souvent."Seldom-when, as far as my experience goes, seems to have passed out of use where archaisms still linger; but anywhen may be heard any day and every day in Surrey and Sussex. Those who would learn the rationale of these words will do well to consult Dr. Richardson's most excellent Dictionary, under the words An, Any, When, and Seldom.

This is at least a step towards Mr. Fraser's wish of seeing anywhen legitimatised; for what superior claim had seldom-when to be enshrined and immortalised in the pages of the poet of the world?

S. W. Singer.Manor Place, South Lambeth.

CHICHESTER: LAVANT

(Vol. vii., p. 269.)Your correspondent C. affirms, as a mark of the Roman origin of Chichester, that "the little stream that runs through it is called the Lavant, evidently from lavando!" Now nobody, as old Camden says, "has doubted the Romanity of Chichester;" but I am quite sure that the members of the Archæological Institute (who meet next summer upon the banks of this same Lavant) would decidedly demur to so singular a proof of it.

C. is informed that, in the fourth volume of the Archæologia, p. 27., there is a paper by the Hon. Daines Barrington, on the term Lavant, which, it appears, is commonly applied in Sussex to all brooks which are dry at some seasons, as is the case with the Chichester river.

"From the same circumstance," it is added, "the sands between Conway and Beaumaris in Anglesey, are called the Lavant sands, because they are dry when the tide ebbs; as are also the sands which are passed at low water between Cartmell and Lancaster, for the same reason."

To trace the origin of the term Lavant, we must, I conceive, go back to a period more remote than the Roman occupation; for that remarkable people, who conquered the inhabitants of Britain, and partially succeeded in imposing Roman appellations upon the greater towns and cities, never could change the aboriginal names of the rivers and mountains of the country. "Our hills, forests, and rivers," says Bishop Percy, "have generally retained their old Celtic names." I venture, therefore, to suggest, that the British word for river, Av, or Avon, which seems to form the root of the word Lavant, may possibly be modified in some way by the prefix, or postfix, so as to give, to the compound word, the signification of an intermittent stream.

The fact that, amidst all the changes which have passed over the face of our country, the primitive names of the grander features of nature still remain unaltered, is beautifully expressed by a great poet recently lost to us:

"Mark! how all things swerveFrom their known course, or vanish like a dream;Another language spreads from coast to coast;Only, perchance, some melancholy stream,And some indignant hills old names preserve,When laws, and creeds, and people all are lost!"Wordsworth's Eccles. Sonnets, xii.W. L. Nichols.Bath.

SCARFS WORN BY CLERGYMEN

(Vol. vii., p. 269.)The mention of the distinction between the broad and narrow scarf, alluded to by me (Vol. vii., p. 215.), was made above thirty years ago, and in Ireland. I have a distinct recollection of the statement as to what had been the practice, then going out of use. I am sorry that I cannot, in answer to C.'s inquiry, recollect who the person was who made it. Nor am I able to specify instances of the partial observance of the distinction, as I had not till long after learned the wisdom of "making a note:" but I had occasion to remark that dignitaries, &c. frequently wore wider scarfs than other clergymen (not however that the narrower one was ever that slender strip so improperly and servilely adopted of late from the corrupt custom of Rome, which has curtailed all ecclesiastical vestments); so that when the discussion upon this subject was revived by others some years ago, it was one to which my mind had been long familiar, independently of any ritual authority.

I hope C. will understand my real object in interfering in this subject. It is solely that I may do a little (what others, I hope, can do more effectually) towards correcting the very injurious, and, I repeat, inadequate statement of the Quart. Review for June, 1851, p. 222. However trifling the matter may be in itself, it is no trifling matter to involve a considerable portion of the clergy, and among them many who are most desirous to uphold both the letter and the spirit of the Church of England, and to resist all real innovation, in a charge of lawlessness. Before the episcopal authority, there so confidently invoked, be interposed, let it be proved that this is not a badge of the clerical order, common to all the churches of Christendom, and actually recognised by the rules, in every respect so truly Catholic, of our own Church. The matter does not, I apprehend, admit of demonstration one way or the other, at least till we have fresh evidence. But to me, as to many others, analogies seem all in favour of the scarf being such a badge; and not only this, but the very regulation of our royal ecclesiastical authorities. The injunctions of Queen Elizabeth, in 1564, seem to mark the tippet as a distinction between clergymen and laymen, who otherwise, in colleges and choirs at least, would have none. I also am strongly of opinion that the tippets mentioned in the 58th and 74th English canons are the two scarfs referred to: the silken tippet (or broad scarf) being for such priests or deacons as hold certain offices, or are M.A., LL.B., or of superior degree; the plain tippet (or narrow scarf) being for all ministers who are non-graduates (Bachelors of Arts were not anciently considered as graduates, but rather as candidates for a degree, as they are still styled in many places abroad); so that all in orders may have tippets. This notion is confirmed by the fact, that the scarf was frequently called a tippet in Ireland within memory. And in a letter, discussing this very subject, in the Gentleman's Mag. (for 1818, part ii. p. 218.7), the testimony of one is given who had for upwards of fifty years considered the two words as identical, and had heard them in his youth used indiscriminately by aged clergymen. It is notorious that in Ireland, time out of mind, tippets have been more generally worn than hoods in parish churches there. I am not sure (though I lay no stress on the conjecture) whether this may not have been in consequence of the option apparently given by the Canons of wearing either hood or tippet.

It is not correct to restrict the customary use of the scarf to doctors, prebendaries, and chaplains. In some cathedrals the immemorial custom has been to assign it to minor canons and clerical vicars also. At Canterbury, indeed, the minor canons, except otherwise qualified, do not wear it. (But is not this an exception? Was it always so? And, by the way, can any cathedral member of old standing testify as to the customary distinction in his church between the two scarfs, either as to size or materials?) The very general use of it in towns cannot be denied.

I may add, that Bishop Jebb used to disapprove of its disuse by country clergymen. In his Charge he requests that "all beneficed clergymen" of his diocese "who are Masters of Arts, or of any superior degree, and who by chaplaincies or otherwise are entitled to the distinction, may with their surplices wear scarfs or tippets." This apparently was his construction of the Canons.

John Jebb.The narrow scarf, called the stole or orarium, is one of the most ancient vestments used by the Christian clergy, representing in its mystical signification the yoke of Christ. Though it may be true that its use is not enjoined by any modern rubric or canon, custom, I think, fully warrants the clergy in wearing it. What other sanction than custom is there for the use of bands?

E. H. A.A great deal of very interesting matter bearing upon this question, both in an ecclesiastical and antiquarian point of view, though no definite conclusion is arrived at, will be found in a pamphlet by G. A. French, entitled The Tippets of the Canons Ecclesiastical.

An Oxford B.C.L.INSCRIPTIONS IN BOOKS

(Vol. vii., p. 127.)The following were lines much used when I was at school, and I believe are still so now:

"This book is mineBy right divine;And if it go astray,I'll call you kindMy desk to findAnd put it safe away."Another inscription of a menacing kind was,—

"This book is one thing,My fist is another;Touch this one thing,You'll sure feel the other."A friend was telling me of one of these morsels, which, considering the circumstances, might be said to have been "insult added to injury;" for happening one day in church to have a book alight on his head from the gallery above, on opening it to discover its owner, he found the following positive sentence:

"This book doant blong to you,So puttem doon."Russell Gole.The following salutary advice to book-borrowers might suitably take its position in the collection already alluded to in "N. & Q.":

"Neither blemish this book, or the leaves double down,Nor lend it to each idle friend in the town;Return it when read; or if lost, please supplyAnother as good, to the mind and the eye.With right and with reason you need but be friends,And each book in my study your pleasure attends."O. P.Birmingham.

Is not this curious warning worthy of preservation in your columns? It is copied from a black-letter label pasted to the inside of an old book cover:

"Steal not this booke, my honest friende,For fear ye gallows be ye ende;For if you doe, the Lord will say,'Where is that booke you stole away?'"J. C.To the collection of inscriptions in books commenced by Balliolensis, allow me to add the following:

"Hic liber est meus,Testis et est Deus;Si quis me quærit,Hic nomen erit."In French books I have seen more than once,—

"Ne me prend pas;On te pendra."An on the fly-leaf of a Bible,—

"Could we with ink the ocean fill,Were ev'ry stalk on earth a quill,And were the skies of parchment made,And ev'ry man a scribe by trade,To tell the love of God aloneWould drain the ocean dry.Nor could the scroll contain the whole,Though stretch'd from sky to sky."George S. Master.Welsh-Hampton, Salop.

I beg to subjoin a few I have met with. Some monastic library had the following in or over its books:

"Tolle, aperi, recita, ne lædas, claude, repone."The learned Grotius put in all his books,—

"Hugonis Grotii et amicorum."In an old volume I found the following:

"Hujus si quæris dominum cognoscere libri,Nomen subscriptum perlege quæso meum."Philobiblion.PHOTOGRAPHIC NOTES AND QUERIES

Head-rests.—The difficulty I have experienced in getting my children to sit for their portraits in a steady position, with the ordinary head-rests, has led me to design one which I think may serve others as well as myself; and I therefore will describe it as well as I can without diagrams, for the benefit of the readers of "N. & Q." It is fixed to the ordinary shifting upright piece of wood which in the ordinary rest carries the semicircular brass against which the head rests. It is simply a large oval ring of brass, about an inch and a half broad, and sloping inwards, which of the following size I find fits the back of the head of all persons from young children upwards:—five inches in the highest part in front, and about four inches at the back. It must be lined with velvet, or thin vulcanised India rubber, which is much better, repelling grease, and fitting quite close to the ring. This is carried forward by a piece of semicircular brass, like the usual rest, and fixes with a screw as usual. About half the height of the ring is a steel clip at each side, like those on spectacles, but much stronger, about half an inch broad, which moving on a screw or rivet, after the sitter's head is placed in the ring, are drawn down, so as to clip the head just above the ears. A diagram would explain the whole, which has, at any rate, simplicity in its favour. I find it admirable. Ladies' hair passing through the ring does not prevent steadiness, and with children the steel clips are perfect. I shall be happy to send a rough diagram to any one, manufacturers or amateurs.

J. L. Sisson.Edingthorpe Rectory.

Sir W. Newton's Explanations of his Process.—In reply to Mr. John Stewart's Queries, I beg to state,

First, That I have hitherto used a paper made by Whatman in 1847, of which I have a large quantity; it is not, however, to be procured now, so that I do not know what paper to recommend; but I get a very good paper at Woolley's, Holborn, opposite to Southampton Street, for positives, at two shillings a quire, and, indeed, it might do for negatives.

Secondly, I prefer making the iodide of silver in the way which I have described.

Thirdly, Soft water is better for washing the iodized paper; if, however, spring water be made use of, warm water should be added, to raise it to a temperature of sixty degrees. I think that sulphate or bicarbonate of lime would be injurious, but I cannot speak with any certainty in this respect, or to muriate of soda.

Fourthly, The iodized paper should keep good for a year, or longer; but it is always safer not to make more than is likely to be used during the season.

Fifthly, If I am going out for a day, I generally excite the paper either the last thing the night before, or early the following morning, and develope them the same night; but with care the paper will keep for two or three days (if the weather is not hot) before exposure, but of course it is always better to use it during the same day.

Wm. J. Newton.6. Argyle Street.

Talc for Collodion Pictures.—Should any of your photographic friends wish to transmit collodion pictures through the post, I would suggest that thin plates of talc be used instead of glass for supporting the film; I find this substance well suited to the purpose. One of the many advantages of its use (though I fear not to be appreciated by your archæological and antiquarian section) is, that portraits, &c., taken upon talc can be cut to any shape with the greatest ease, shall I say suitable for a locket or brooch?

W. P.Headingley, Leeds.

Replies to Minor Queries

Portrait of the Duke of Gloucester (Vol. vii., p. 258.).—I beg to inform Mr. Way that he will find an engraving of "The most hopefull and highborn Prince, Henry Duke of Gloucester, who was borne at Oatlandes the eight of July, anno 1640: sould by Thos. Jenner at the South entry of the Exchange," in a very rare pamphlet, entitled:

"The Trve Effigies of our most Illustrious Soveraigne Lord, King Charles, Queene Mary, with the rest of the Royall Progenie: also a Compendium or Abstract of their most famous Genealogies and Pedegrees expressed in Prose and Verse: with the Times and Places of their Births. Printed at London for John Sweeting, at the Signe of the Angell, in Pope's Head Alley, 1641, 4to."

For Henry Duke of Gloucester, see p. 16.:

"What doth Kingdomes happifieBut a blesst Posteritie?This, this Realme, Earth's Goshen faire,Europe's Garden, makes most rare,Whose most royall Princely stemme(To adorne theire Diadem)Two sweet May-flowers did produce,Sprung from Rose and Flower-de-Luce."Φ.Richmond, Surrey.

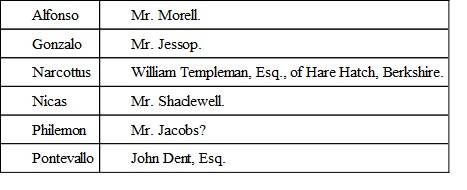

Key to Dibdin's "Bibliomania" (Vol. vii., p. 151.).—There are some inaccuracies in the list of names furnished by W. P., which may be corrected on the best authority, namely, that of Dr. Dibdin himself, as put forth in his "new and improved edition" of the Bibliomania, with a supplement, "including a key to the assumed characters in the drama," 8vo., 1842. According to this supplement we are to interpret as follows:

A complete "key" is not furnished; but there is reason, I think, to doubt a few of the other names in W. P.'s list. Moreover, in the edition of 1842, several other pseudonymes are introduced, which do not appear in the list; namely, that of Florizel, for Joseph Haslewood; Antigonus; Baptista; Camillo; Dion; Ferdinand; Gonsalvo; Marcus; and Philander; respecting whom some of your readers may possibly enlighten us further. As to the more obvious characters of Atticus, Prospero, &c., see the Literary Reminiscences, vol. i. p. 294.

μ.High Spirits a Presage of Evil ("N. & Q." passim).—In a case lately detailed in the newspapers, a circumstance is mentioned which appears to me to come under the above heading.

In the inquiry at the coroner's inquest, on Feb. 10, 1853, concerning the death of Eliza Lee, who was supposed to have been murdered by being thrown into the Regent's Canal, on the evening of the 31st of January, by her paramour, Thomas Mackett,—one of the witnesses, Sarah Hermitage, having deposed that the deceased left her house in company with the accused at a quarter-past ten o'clock in the evening of the 31st, said as follows:

"Deceased appeared in particularly good spirits, and wanted to sing. Witness's husband objected; but she would insist upon having her way, and she sang 'I've wander'd by the Brook-side.'"

The deceased met with her death within half an hour after this.

Cuthbert Bede.Hogarth's Works.—Observing an inquiry made in Vol. vii., p. 181. of "N. & Q." about a picture described in Mrs. Hogarth's sale catalogue of her husband's effects in 1790, made by Mr. Haggard, I am induced to ask whether a copy of the catalogue, as far as it relates to the pictures, would not be a valuable article for your curious miscellany? It appears from all the lives of Hogarth, that he early in life painted small family portraits, which were then well esteemed. Are any of them known, and where are they to be seen? Were they mere portraits, or full-length? Are any of them engraved? I had once a picture, of about that date, which represented a large house with a court-yard, and a long garden wall, with a road and iron gate, something like the old wall and road of Kensington Gardens, with the master, mistress, and dog walking in front of the house, and evidently portraits. I always suspected it might be by Hogarth; but I am very sorry to say I parted with it at auction for a few shillings. It was (say) two feet square: the figures were about four inches in height, and dressed in the then fashion. I would further ask if any oil painting or sketches are known of the minor engravings, such as "The Laughing Audience," "The Lecture," "The Doctors," &c.?

An Amateur.Town Plough (Vol. vi., p. 462.; Vol. vii., p. 129.).—In Vol vi., p. 462., Gastron notices the Town Plough; and it is again noticed by S. S. S. (Vol. vii., p. 129.) as never having been seen by him mentioned in ancient churchwardens' accounts.

Not ten years since there was in the belfry of Caston Church, Northamptonshire, a large clumsy-looking instrument, the use of which was not apparent at first sight, being a number of rough pieces of timber, put together as roughly. On nearer inspection, however, it turned out to be a plough, worm-eaten and decayed, I should think at least three times as large and heavy as the common ploughs of the time when I saw the one in question. I have often wondered at the rudeness and apparent antiquity of that plough, and whether on "Plough Monday" it had ever made the circuit of the village to assist in levying contributions.

I have only for a week or two been in the possession of "N. & Q." when having accidentally, and for the first time, met with the Number for that week, I could not resist the temptation of becoming the owner of the complete series. Under these circumstances, you will excuse me if I am asking a question which may have been answered long since. What is the origin of Plough Monday? May there not be some connexion with the Town Plough? and that the custom, which was common when I was a boy, of going round for contributions on that day, may not have originated in collecting funds for the keeping in order, and purchasing, if necessary, the Town Plough?

Brick.Shoreditch Cross and the painted Window in Shoreditch Church (Vol. vii., p. 38.).—I beg to acquaint your correspondent J. W. B. that although I had long searched for an engraving of Shoreditch Cross, my labour was lost. The nearest approach to it will be found in a modern copy of a plan of London, taken in the time of Elizabeth, in which its position is denoted to be on the west side of Kingsland Road; but, from records to which I have access, I believe that the cross stood on the opposite side, between the pump and the house of Dr. Burchell. Most likely its remains were demolished when the two redoubts were erected at the London ends of Kingsland and Hackney Roads, to fortify the entrance to the City, in the year 1642.

The best accounts that I have seen of the painted window are in Dr. Denne's Register of Benefactions to the parish, compiled in 1745, and printed in 1778; and Dr. Hughson's History of London, vol. iv. pp. 436, 437.

Henry Edwards.Race for Canterbury (Vol. vii., pp. 219. 268.).—It is probable that the lines

"The man whose place they thought to take,Is still alive, and still a Wake,"are erroneously written on the print referred to; but I have no doubt of having seen a print of which (with the variation of "ye think" for "they thought") is the genuine engraved motto.