Полная версия

Полная версияLippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol. XVI., December, 1880.

Other old churches still dot the Virginia soil—St. John's, Richmond; Pohick Church, Westmoreland county; Christ Church, Lancaster county; St. Anne's, Isle of Wight county. Their antiquities, and those of other ancient sanctuaries of the Old Dominion, have been painstakingly set forth by Bishop Meade and other zealous chroniclers, and their attractiveness is increased, in most cases—as at Jamestown—by the loneliness of their surroundings. Another old church, left in the midst of sweet country sights and gentle country sounds, is St. James's, Goose Creek, South Carolina. St. Michael's and St. Philip's at Charleston in the same State have heard the roar of hostile cannon, but have come forth unscathed. The demolished Brattle Street Church in Boston was not the only one of our sacred edifices to be wounded by cannonballs, for the exigences of the fight more than once, during the Revolution and the civil war, brought flame and destruction within the altar-rails of churches North and South.

The growth of the Roman Catholic Church in America has been so recent that it can show but few historical landmarks. The time-honored cathedral at St. Augustine, Florida, and the magnificent ruin of the San José Mission near San Antonio, Texas, and one or two weather-stained little chapels in the North-west, are nearly all the churches that bring to us the story of the priestly work of the Roman ecclesiastics during the colonial days.

We have no State Church, and the different Presidents have made a wide variety of choice in selecting their places of worship in Washington. St. John's, just opposite the White House, has been the convenient Sunday home of some of them: others have followed their convictions in Methodist, Presbyterian, Unitarian and other churches. But the city of Washington is itself too young to be able to boast any very ancient associations in its churches, and few of its temples have been permitted to record the names of famous occupants during a series of years. Our whole country, indeed, is a land of many denominations and a somewhat wandering population; and older cities than Washington have found one church famous for one event in its history, and another for another, rather than, in any single building, a series of notable occurrences running through the centuries. The nearest approach to the record of a succession of worthies occupying the same church-seats year after year is to be found in the chronicles of our oldest college-chapels, as, for instance, at Dartmouth, where the building containing the still-used chapel dates from 1786. But though poverty and custom unite in making our colleges conservative, their growth in numbers demands, from time to time, new and more generous accommodations for public worship; and so the little buildings of an earlier day are either torn down or kept for other and more ignoble uses, like Holden Chapel at Harvard. This quaint little structure was built in 1744, and is now used for recitation-rooms, but at one period in its career it served as the workshop of the college carpenter.

In the years since our grandfathers built their places of worship we have seen strange changes in American church buildings—changes in material, location and adaptation to ritual uses. We have had a revival of pagan temple-building in wood and stucco; we have seen Gothic cathedrals copied for the simplest Protestant uses, until humorists have suggested that congregations might find it cheaper to change their religion than their unsuitable new churches; we have ranged from four plain brick walls to vast and costly piles of marble or greenstone; we have constructed great audience-rooms for Sunday school uses alone, and have equipped the sanctuary with all culinary attachments; we have built parish-houses whose comfort the best-kept mediæval monk might envy, and we have put up evangelistic tabernacles only to find the most noted evangelists preferring to work in regular church edifices rather than in places of easy resort by the thoughtless crowd of wonder-seekers. But not all these doings have been foolish or mistaken: some of them have been most hopeful signs, and the next century will find excellent work in the church-building of our day. The Gothic and Queen Anne revivals, at their best, have promoted even more than the old-time honesty in the use of sound and sincere building-material; and not a few of our newer churches prove that our ecclesiastical architects have something more to show than experiments in fanciful "revivals" that are such only in name. We shall continue to do well so long as we worthily perpetuate the best material lesson taught by our grandfathers' temples—the lesson of downright honesty of construction and of a union between the spirit of worship and its local habitation.

CHARLES F. RICHARDSON.WILL DEMOCRACY TOLERATE A PERMANENT CLASS OF NATIONAL OFFICE HOLDERS?

It is no doubt a public misfortune that so much of that thoughtful patriotism which, both on account of its culture and its independence, must always be valuable to the country, should have been wasted, for some time past, upon what are apparently narrow and unpractical, if not radically unsound, propositions of reform in the civil service. There is unquestionably need of reform in that direction: it would be too much to presume that in the generally imperfect state of man his methods of civil government would attain perfection; but it must be questioned whether the subject has been approached from the right direction and upon the side of the popular sympathy and understanding. At this time propositions of civil-service reform have not even the recognition, much less the comprehension, of the mass of the people. Their importance, their limitations, their possibilities, have never been demonstrated: no commanding intellectual authority has ever taken up the subject and worked it out before the eyes of the people as a problem of our national politics. It remains a question of the closet, a merely speculative proposition as to the science of government.

What, then, are the metes and bounds of this reform? How much is demanded? How much is practicable?

Not attempting a full answer to all of these questions, and intending no dogmatic treatment of any, let us give them a brief consideration from the point of view afforded by the democratic system upon which the whole political fabric of the United States is established. We are to look at our civil-service reform from that side. Whatever in it may be feasible, that much must be a work in accord with the popular feeling. It may be set down at the outset, as the first principle of the problem, that any practicable plan of organizing the public service of the United States must not only be founded upon the general consent of the people, but must also have, in its actual operation, their continual, easy and direct participation. Any scheme, no matter by what thoughtful patriot suggested, no matter upon what model shaped, no matter from what experience of other countries deduced, which does not possess these essential features can never be worth the serious attention of any one who expects to accomplish practical and enduring results.

(Possibly this may seem dogmatic, to begin with; but if we agree to treat the question as one in democratic politics, the principle stated becomes perfectly apparent.)

It must be fair, then, and for the purposes of this article not premature, to point out that the measure which is especially known as "civil-service reform," and which has been occasionally recognized in the party platforms along with other generalities, is one whose essence is the creation of a permanent office-holding class. Substantially, this is what it amounts to. A man looking forward to a place in the public service is to regard it as a life occupation, the same as if he should study for a professional career or learn a mechanical trade. Once in office, after a "competitive examination" or otherwise, he will expect to stay in: he will hold, as the Federal judges do, by a life-tenure, "during good behavior." This is now substantially the system of Great Britain, which, in the judgment of Mr. Dorman B. Eaton, is so much better than our own as to actually reduce the rate of criminality in that country, and which, he declares, only political baseness can prevent us from imitating. A change of administration there, Mr. Eaton adds, only affects a few scores of persons occupying the highest positions: the great mass of the officials live and die in their places, indifferent to the fluctuation of parliamentary majorities or the rise and fall of ministries.

We must ask ourselves does this system accord with American democracy?

A little more than half a century has passed since John Quincy Adams, unquestionably the best trained and most experienced American administrator who ever sat in the Presidency, undertook to establish in the United States almost precisely the same system as that which Great Britain now has. Admission to the places was not, it is true, by means of competitive examination, but the feature—the essential feature—of permanent tenure was present in his plan. Mr. Adams took the government from Mr. Monroe without considering any change needful: his Cabinet advisers even included three of those who had been in the Cabinet of his predecessor, and these he retained to the end, though at least one of the three, he thought, had ceased to be either friendly or faithful to him. Retaining the old officers, and reappointing them if their commissions expired, selecting new ones, in the comparatively rare cases of death, resignation or ascertained delinquency, upon considerations chiefly relating to their personal capabilities for the vacant places, Mr. Adams was patiently and faithfully engaged during the four years of his Presidency in establishing almost the precise reform of the national service which has been in recent times so strenuously urged upon us as the one great need of the nation—the administrative purification which, if effectually performed, would prove that our system of government was fit to continue in existence. Mr. Adams's plan did, indeed, seem excellent. It commanded the respect of honest but busy citizens absorbed in their private affairs and desirous that the government might be fixed, once for all, in settled grooves, so that its functions would proceed like the steady progress of the seasons. It was an attempt to run the government, as has been sometimes said, "on business principles." The President was to proceed, and did proceed, as if he had in charge some great estate which he was to manage and direct as a faithful and exact trustee. This, no one can deny, had the superficial look of most admirable administration.

But President Adams had left out of account largely what we are compelled to sedulously consider—public opinion. He had acquired most of his experience abroad, and his principal service at home, as Secretary of State, had been in a remarkably quiet time, when party movements were neither ebbing nor flowing, so that he had forgotten how strong and vigorous the democratic feeling was amongst the population of these States. This is a forgetfulness to which all men are liable who long occupy official position, and who seldom have to submit themselves to that severe and rude competitive examination which the plan of popular elections establishes. Unfortunately for him, he was not responsible to a court of chancery for the management of his trust, but to a tribunal composed of a multitude of judges. His accounts were to be passed upon not by one learned and conservative auditor guided by familiar precedents and rules of law, but a great, tumultuous popular assembly, which would approve or disapprove by a majority vote. When, therefore, it appeared to the people that he was forming a body of permanent office-holders—was recruiting a civil army to occupy in perpetuity the offices which they, the mass, had created and were taxed to pay for—the fierce, and in many respects scandalous, partisan assault which Jackson represented, if he did not direct, gathered overwhelming force. It seemed to the popular view that a narrow, an exclusive, an aristocratic system was being formed. The President appeared to be, while honestly and carefully preserving their trust from waste or loss, committing it to a control independent of them—an official body which, having a permanent tenure, would be altogether indifferent to their varying desires. Such a scheme of government was therefore no more than an attempt to stand the pyramid on its apex: Mr. Adams's administration, supported chiefly by those whose aspirations were for an honest and capable bureaucracy, and who could not or would not face the rude questionings of democracy, ended with his first four years, and went out in such a whirlwind of partisan opposition as brought in, by reaction, the infamous "spoils system" that at the end of half a century we are but partially recovered from.

To designate more particularly the great fact which had been disregarded in this notable experiment of fifty years ago, and which is apparently not sufficiently considered in the measures of reform that have been more recently pressed upon us, we may declare that the government of the United States is, as yet, the direct outcome of what may be called the political activity of the people. Whether or not, having read history, we must anticipate a time here when the many, weary of preserving their own liberties, will resign their power to a few, it is certain that no such inclination yet appears. The government is the product of the public mind and will when these are moved with reference to the subject. It is created freshly at short intervals, and the manner of the creation is seldom languid or careless, but usually earnest, intense and heated. Upon this point there has no doubt been much misapprehension. As it has happened—perhaps rather oddly—that those of our thoughtful patriots whose warnings and appeals have reached public notice have had their experiences mostly in city life, surrounded by the peculiar conditions which exist there, the conclusions they have drawn in some respects are applicable only to their own surroundings. They have discovered persons who had forgotten or did not believe that liberty could be bought only with the one currency of eternal vigilance, and coupled with these others who were too busy to attend to the active processes by which the government is from time to time renewed; and they have concluded, with fatal inaccuracy of judgment, that this exceptional disposition of a small number of persons was a type of the whole population. Nothing could be more absurdly untrue. Outside of a very limited circle no such political fatigue exists. The people generally are deeply interested in public affairs and willing to attend to their own public duties. Their concern in regard to measures, methods and candidates is seldom laid aside. The political activity to which we have called attention thus at some length is earnest, persistent and exacting.

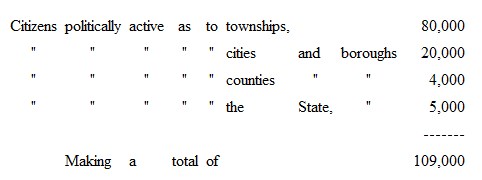

It will be useful for the reformer of the civil service to give some study to the manifestations of this activity. He will find it one of the most marked and characteristic features in the life of the American people. If he will take the pains to examine the civil organization of the country, he will find that its roots run to every stratum of society. The number of persons interested in politics, not as a speculative subject, but as a practical and personal one, is wonderfully great. Thus, in most of the States there exists that modification of the ancient Saxon system of local action by "hundreds"—the township organization. This alone carries a healthy political movement into the farthest nook and corner of the body politic: every citizen of common sense may well be consulted in this primary activity, and every household may be interested in the question whether its results are good or bad. But besides this, simple and slightly compensated as are the positions belonging to the township, there are in every community many willing to fill them. To be a supervisor of the roads,1 to be township constable and collector of the taxes, to audit the township accounts, to be a member of the school board, to be a justice of the peace, is an inclination—it may be a desire—entertained by many citizens; and if the ambition may seem to be a narrow one, its modesty does not make it unworthy or discreditable. But these men alone, active in the politics of townships, form a surprising array. If we consider that in Pennsylvania there are sixty-seven counties, with an average of say forty townships in each, here are twenty-six hundred and eighty townships, having each not less than ten officials, and making nearly twenty-seven thousand persons actually on duty at one time in a single State in this fundamental branch of the service. And if we estimate that besides those who are in office at least two persons are inclined and willing, if not actually desirous, to occupy the place now filled by each one—a very moderate calculation—we multiply twenty-six thousand eight hundred by three, and have over eighty thousand persons whose minds are quick and active in local politics on this one account. But we may proceed further. There are the cities and boroughs, their official business more complex and laborious, and in most cases receiving much higher compensation. The competition for these is in many instances very great: in the case of large cities we need not waste words in elaborating the fact. It is difficult to estimate the number of persons to whom the municipal corporations give place and pay compensation in the State of Pennsylvania, but five thousand is not an extravagant surmise, while it would be equally reasonable to presume that for each place occupied at least three others would be willing to fill it, so that on this account we may make a total of twenty thousand. But there are also the county offices. Besides the judicial positions, altogether honorable, held by long terms of election and receiving liberal compensation, there are in each county an average of fifteen other officials, making in the State, in round numbers, one thousand. These, again, may be multiplied by four: there are certainly three waiting aspirants for each place. But ascend now to the State system, with its several executive departments, the legislature, the charitable and penal institutions and the appointments in the gift of the governor. Great and small, these may reach one thousand (the Legislature alone, with its officers and employés, accounts for over three hundred), and certainly there are at least five persons looking toward each of the several places.

Upon such an estimate, then, of the political activities of one State we have such a showing as this:

Some allowance should be made, no doubt, for persons whose inclinations for position cover all the different fields—who may be said to be watching several holes. But we have not considered how many citizens of Pennsylvania are inclined to national positions—the Presidency, seats in Congress or some of the numerous places in the general service of the Federal government. These two classes, it is probable, would offset each other.

Subtracting, however, the odd thousands from the total stated, we may fix at one hundred thousand the number of citizens in the one State who, by reason of occupying some position of public duty or of being inclined to fill one, are actively interested in the subject of politics. This is almost exactly one-seventh of the whole number of voters in the State: it presents the fact that in every group of seven citizens there is one, presumably of more than the average in capacity and intelligence, whose mind is quick and sensitive to every question affecting political organization. We are brought thus to the same point which we reached by an observation of the township system—the fact that every part of society is permeated by the general political circulation. It is like the human organism: nerves and blood-vessels extend, with size and capacity proportioned for their work, to the most remote extremity, and the whole is alive.

Let us, however, guard strictly, at this point, against a possible misconception. It is not to be understood that these one hundred thousand citizens are simply "office-seekers," using the ordinary and offensive sense of the term. The activity in affairs which we describe is distinct from a sordid desire to grab the emoluments of office. The vast majority of the places, including all those in the townships—which, with the aspirants to them, make four-fifths of the whole—are either without any pay at all or have an amount so small as to be beneath our consideration. But a small part of the offices which we have enumerated carry emoluments sufficient to furnish a living for the most economical incumbent. The inspiration of the political interest evidenced by this one-seventh part of the citizenship is not an unworthy one at all: on the contrary, it is that essential democratic inclination without which our form of government must quickly stagnate. It would be foolish to say that no selfish motive enters into this tremendous manifestation of energy and effort (until humanity assumes a higher form the moving power of the mercenary principle must be very great), but it is fair and it is accurate to ascribe to the men in affairs a much loftier and more honorable impulse—the aspiration to share in the conduct of their own government, the unwillingness to be ignored or excluded in the administration of what is universally denominated a common trust. That they enjoy, if they do not covet, such pecuniary advantage as their places bring is reasonable, but it is true, to their credit, that they do appreciate more than this the honor that attaches to the public station and the pleasure which may be experienced in the discharge of its conspicuous duties.

Let us presume that even this imperfect study of the political activities of a single State may present some conception of the tremendous force and energy that go to the making, year by year, of the various branches of our government. Certainly, any student of this field may accept with respect the admonition that there is no languor, no fatigue, no feeling of genteel disgust with politics, in what has thus been presented him. If, then, his plan of reorganization for the civil service is intended to be set up without consulting the popular inclination, or possibly even in opposition to it, he may well stand hesitant as to his likelihood of success. The question may confront him at once: Is the organization of a permanent official class in the administration of the general government likely to accord with the desires of the people? And we may add, Is it consistent with the general character of our form of government? Is it not attended by conclusive objections?

It is not the purpose of this article to attempt answering these questions fully. We do not propose to throw ourselves across the path of those undoubtedly sincere, and probably wise, students of this subject who have arrived at the positive conclusion that to establish a permanent tenure for the great body of the national office-holders, and to appoint to vacancies among them upon the tests of a competitive or other examination, is the panacea for all our public disorders, the regenerative process which will lift our whole system into a higher and purer atmosphere. We do not say that these gentlemen may not be right, but we are willing to examine the subject.

Upon viewing, then, the tremendous popular activity in local and State affairs—and we must reflect that there is "more politics to the square foot" in some of the newer States than there is in Pennsylvania—the inquiry is natural whether this stops short of all national politics. Certainly it does not. The offices in the general government, though their importance and their influence are usually overestimated, are a great object of attention with the whole country. The vehement democratic movement toward them that marked the time of Jackson is still apparent, though it proceeds with diminished force and is regulated and tempered by the strong protest which has been made against the scandals of the "spoils system," and against the theory that government by parties must be a continual struggle for plunder. It is noticeable that no administration has ever really attempted the formation of an irremovable body of officials. No party has ever yet explicitly declared itself in favor of such a policy. No actual leader of any party, bearing the responsibility of its success or failure in the elections, has ever yet sincerely and persistently advocated the measure. None wish to undertake so tremendous a task. He would indeed be a powerful orator who could carry a popular gathering with him in favor of the proposition that hereafter the holding of office was to be made more exclusive—that the people were to put away from themselves, by a renunciation of their own powers, the expectancy of occupying a great part of the public places. Rare as may be the persuasive ability of the true stump-orator, and serene as his confidence may be in his powers, there would be but few volunteers to enter a campaign upon such a platform as that. It would be a forlorn hope indeed.