Полная версия

Полная версияHistoric Towns of New England

Providence contributed its full share to the Revolution. Stephen Hopkins signed the Declaration of Independence with a tremulous hand, but a firm heart. Troops were freely furnished and privateers brought wealth to the town. The second division of the French contingent passed the winter of 1782 in encampment on Harrington’s Lane. The street is now known as Rochambeau Avenue. Newport, hitherto the more important port, lost her commerce through the British occupation. The natural drift of commerce to the farthest inland waters available was precipitated by these political changes. Newport never recovered her lost prestige, and Providence developed rapidly after the peace. Voyages, which had been mostly to the West Indies with an occasional trip to Bilbao and the Mediterranean, soon stretched around the world to harvest the teeming wealth of the Chinese and Indian seas. The General Washington, the first vessel from Providence in that trade, sailed in 1787. Edward Carrington sent out and received the last vessels in 1841. In the early years of the nineteenth century, the profits of the Oriental trade were very great.

The manufacture of cotton was attempted by several parties, but it was not established in Providence. Samuel Slater located in Pawtucket in 1790. He was induced to come to our State through the sagacity, enterprise and abundant capital of Moses Brown. After about a year, a glut of yarns occurred, and Almy, Brown and Slater had accumulated nearly six thousand pounds. Brown said: “Samuel, if thee goes on, thee will spin up all our farms.” The manufacture extended rapidly and became the chief source of the prosperity of the State. It absorbed the capital, which was gradually withdrawn from commerce and shipping.

An important element in the development of our city has been the free banking system. The first institution in our State and the second in New England was the Providence Bank, chartered in 1791.

Newspapers only slightly affected the life of the eighteenth century. They began, in a humble way, the great part they were to play in later, modern development. The Providence Gazette and Country Journal was first published in 1762 by William Goddard. The Manufacturers’ and Farmers’ Journal, still continuing its prosperous career, appeared in 1820. The Gazette was enlivened by advertisements in verse, of which this is a specimen, from the year 1796:

“A bunch of Grapes is Thurber’s sign,A shoe and boot is made on mine,My shop doth stand in Bowen’s Lane,And Jonathan Cady is my name.”Housekeepers in our day consider the servant-girl question a hard problem, but hear the complaint a century ago. There had been taken away “from the servant girls in this town, all inclination to do any kind of work, and left in lieu thereof, an impudent appearance, a strong and continued thirst for high wages, a gossiping disposition for every sort of amusement, a leering and hankering after persons of the other sex, a desire of finery and fashion, a never-ceasing trot after new places more advantageous for stealing, with a number of contingent accomplishments, that do not suit the wearers. Now if any person or persons will restore that degree of honesty and industry, which has been for some time missing,” then this rugged censor offers $500 reward.

In 1767 the first regular stage-coach was advertised to Boston. In 1793 Hatch’s stages ran to Boston and charged the passengers a fare of one dollar, the same sum which the railway charges to-day. In 1796 a navigable canal was projected to Worcester, John Brown being an active promoter. The project was not carried through until 1828, when the packet-boat Lady Carrington passed through the Blackstone Canal. The enterprise had poor success. John Brown built Washington Bridge across the lower Seekonk, connecting the eastern shore to India Point, where the wealth of Ormus and of Ind was discharged from the aromatic ships. In this period the first steamboat came from New York around Point Judith and connected with stages to Boston.

The international disputes concerning the embargo and non-intercourse with Great Britain, which led up to the War of 1812, found Providence opposed in opinion to the Executive of the United States. But the opposition was loyal and the government received proper support. Peace was very welcome when it was proclaimed in 1815. This year, a tremendous gale swept the ocean into the bay and the bay into the river, carrying ruin in their path. The waters were higher by some seven feet than had ever been known. The fierce winds carried the salt of the seas as far inland as Worcester. Thirty or forty vessels were dashed through the Weybosset Bridge into the cove above. Others were swept from their moorings and stranded among the wharves. Shops were smashed or damaged and the whole devastation cost nearly one million of dollars – a great sum in those days. It was a radical measure of improvement. New streets were opened and better stores rose amid the ruins. South Water and South West Water Streets date hence, and Canal Street was opened soon after.

In 1832 the city government was organized, with Samuel W. Bridgham for mayor. A serious riot occurring the previous year had shown that the old town government was outgrown. The railways to Boston and Stonington changed the course of transportation. In 1848 the Worcester connection, the first intersecting or cross line in New England, gave direct intercourse with the West.

We sent out Henry Wheaton, one of the masters of international law, and we adopted Francis Wayland, – a citizen of the world, – who set an enduring mark on Rhode Island. President of Brown University, 1827-1855, his work in the American educational system has not yet yielded its full fruit. He brought teacher and pupil into closer contact by the living voice. He projected a practical method for elective studies and put it in operation at Brown University in 1850. Started too soon, and with insufficient means, it opened the way to success, when the larger universities inaugurated similar methods after the Civil War. Nine hundred and forty-six students now attend where Manning and Wayland taught.

An armed though bloodless insurrection in 1842 brought our State to the verge of revolution. The old charter of 1663 limited suffrage to freeholders and their oldest sons. Thomas Wilson Dorr was the champion of people’s suffrage. His party elected him governor with a legislature, by irregular and illegitimate voting. They mustered in arms and tried to seize the State arsenals in our city. Dorr had a strong intellect; he was a sincere and unselfish patriot, though perverse and foolish in his conduct of affairs. The suffrage was widened by a new constitution in 1843, which has just been revised by a constitutional commission.

The early cotton manufacture was fostered by the well-distributed water-power of Rhode Island. The glacial grinding of the land had left numerous ponds and minor streams, – admirable reservoirs of water-power, – just the facilities needed for weak pioneers. As the century advanced, greater force was needed. About 1847 George H. Corliss bent his talents and energies to extend the power of the high-pressure steam-engine. He adapted and developed better cut-off valves, which preserved the whole expansive force of the steam, stopped off before it filled the cylinder. It was a new lever of Archimedes, and Corliss’s machines went over the whole world. This new mastery of force stimulated all industries.

Our little community showed its customary military spirit in 1861. Governor William Sprague mustered troops with great energy. After the famous Massachusetts 6th, the Rhode Island 1st Militia with its 1st Battery were the first reinforcements which arrived at Washington. In field artillery, our volunteers were especially proficient.

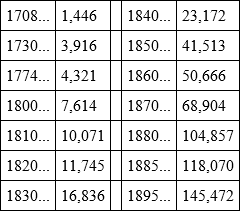

The growth of the population of Providence is shown in the following table:

We could not notice all parts of Providence in this cursory survey. Small as well as large implements of iron, jewelry and silver, the invention and immense production of wood-screws, india-rubber, worsted, – all these complicated industries have built up an extending and encroaching city, until now three hundred thousand people dwell within a radius of ten miles from our City Hall.

Old Providence, the home of Williams and the Quakers, is fading away. The “Towne Streete,” its meandering curves gradually straightening, will hardly be recognized a century hence. The Mowry house, the homes of Stephen and Esek Hopkins, are small, when compared with the mansions of John Brown, Thomas P. Ives, Sullivan Dorr and Edward Carrington; while the solid comfort prevailing in the eighteenth century, as embodied in these houses, is surpassed, though it may not be bettered, by the more pretentious domestic architecture of our day. The Independent worshipers in the First Baptist and First Congregational churches would feel strange under the domes of the beautiful Central Congregational. The Anglicans of the first St. John’s would be bewildered by the pointed arches of St. Stephen’s. The few Catholic immigrants, bringing the Host across the seas with tender care, and resting at St. Peter and St. Paul’s, would be amazed by the swarm of well-to-do citizens clustering beneath the massive towers of the Cathedral.

The industrial and economic evolution is fully as great as the æsthetic and architectural. The crazy little organism of Almy, Brown and Slater is replaced by the long, whirling shafts, the spindled acres of the Goddards’ Ann and Hope Mill at Lonsdale. The homely security of the market house (present Board of Trade), the Providence Bank and the “Arcade” is overshadowed by the City Hall, the Rhode Island Hospital and Rhode Island Hospital Trust Company. University Hall burgeons into the fair arches of Sayles Hall. No medieval builder worked more reverently than Alpheus C. Morse, as he devotedly wrought at his task, getting the best lines into stone and lime.

Not always does the work of the modern builders tend toward beauty. The masterly brick arcades of Thomas A. Teft kept the city’s approaches for a half-century. Swept away by the more convenient passenger station of the New York and New Haven Railway, they will leave behind many regrets. The magnificent marble State House will lift the observer away from and above all the buildings below.

The growth of Providence runs even with the State’s, except in the excrescent luxury of Newport in its summer bloom. We cannot stand still like Holland; we must look outward or decay. The American destiny is reaching out, notwithstanding the caution of the prudent, perhaps of the judicious. The mystic Orient, no longer mysterious, beckons from the West instead of the East. It led the Browns, Iveses, Carringtons, Maurans, and their captains, the Holdens, Ormsbees, Paiges and Comstocks, to opulence. Their descendants, with more abundant capital, ready skill and better organization, ought not to lag in the world’s march. Men must be forthcoming.

There has been always a cosmopolitan flavor in the little State, isolated between the restless intellectual energy of Massachusetts and the steady Puritan development of Connecticut. Boston had more trade than Providence and Newport; she was not so truly commercial. The larger Franklin went over to Pennsylvania, but the next man, Stephen Hopkins, stayed in Rhode Island. The seed which Berkeley planted sprouted in Channing, and that influence went throughout New England. The little State has never been without ideas.

HARTFORD

“THE BIRTHPLACE OF AMERICAN DEMOCRACY”

By MARY K. TALCOTT

AMONG the historic cities of New England, Hartford claims a foremost place. Not only was its settlement of great consequence at the time, but for historical importance and far-reaching results this colony’s claims to attention are second only to those of Plymouth and Boston. The foundation of Hartford was a further application and development of the ideas that brought the Puritans to this country, and, to quote the historian, Johnston, —

“Here is the first practical assertion of the right of the people, not only to choose, but to limit the powers of their rulers, an assertion which lies at the foundation of the American system… It is on the banks of the Connecticut, under the mighty preaching of Thomas Hooker, and in the constitution to which he gave life, if not form, that we draw the first breath of that atmosphere which is now so familiar to us. The birthplace of American democracy is Hartford.”

This constitution, first promulgated in Hartford, was the first written constitution in history which was adopted by a people and which also organized a government. John Fiske says:

“The compact drawn up in the Mayflower’s cabin was not, in the strict sense, a constitution, which is a document defining and limiting the functions of government. Magna Charta partook of the nature of a written constitution as far as it went, but it did not create a government.”

On the 14th of January, 1639, the freemen of the three towns, Windsor, Hartford, and Wethersfield, assembled at Hartford, and drew up a constitution, consisting of eleven articles, which they called the “Fundamental Orders of Connecticut,” and under this law the people of Connecticut lived for nearly two centuries, as the Charter granted by King Charles II., in 1662, was simply a royal recognition of the government actually in operation. Another writer says:

“We honor the limitations of despotism which are written in the twelve tables; the repression of monarchical power in Magna Charta, in the Bill of Rights, and in that whole undefinable creation, as invisible and intangible as the atmosphere but like it full of oxygen and electricity, which we call the British Constitution. But in our Connecticut Constitution we find no limitation upon monarchy, for monarchy is unrecognized; the limitations are upon the legislature, the courts, and executive. It is pure democracy acting through representation, and imposing organic limitations. Even the suffrage qualification of church membership, which was required by our older sister Colony of Massachusetts, was omitted. Here in a New England wilderness a few pilgrims of the pilgrims, alive to the inspirations of the common law and of the British Constitution, so full of Christianity that they felt the great throb of its heart of human brotherhood, and so full of Judaism that they believed themselves in some special sense the people of God, made a written constitution, to be a supreme and organic law for their State.”

But for the immediate inspiration of this document we must look to a “lecture,” preached by Mr. Hooker on Thursday, May 21, 1638, before the legislative body of freemen. Dr. Bacon says of it:

“That sermon, by Thomas Hooker, is the earliest known suggestion of a fundamental law, enacted, not by royal charter nor by concession from any previously existing government, but by the people themselves, – a primary and supreme law by which the government is constituted, and which not only provides for the free choice of magistrates by the people, but also sets the bounds and limitations of the power and place to which each magistrate is called.”

But we must know something of a people to whom such doctrines were preached – of a people capable of receiving and applying such truths. It is said that three kingdoms were sifted to furnish the men who settled New England, and it may also be said that the Massachusetts Colony was sifted to supply the Connecticut settlers. Three of the eight Massachusetts towns, Dorchester, Watertown, and Newtown (now Cambridge), were not in full agreement with the other five, especially on the fundamental feature of the Massachusetts polity, the limitation of office-holding and the voting privilege to church-members. At first the majority were unwilling to grant the minority “liberty to remove.” John Haynes was made Governor of Massachusetts in 1635, probably with the hope of retaining his friends in the Colony. But their desire to leave was too strong; small parties of emigrants made their way to the banks of the Connecticut during the year 1635, but the main body of the colonists did not leave until the spring of 1636. Dr. Benjamin Trumbull, the first historian of Connecticut, writing more than one hundred years ago, says:

“About the beginning of June Mr. Hooker, Mr. Stone, and about a hundred men, women, and children took their departure from Cambridge, and travelled more than a hundred miles thro’ a hideous and trackless wilderness to Hartford. They had no guide but their compass; made their way over mountains, thro’ swamps, thickets, and rivers, which were not passable but with great difficulty. They had no cover but the heavens, nor any lodgings but those which simple nature afforded them. They drove with them a hundred and sixty head of cattle, and by the way subsisted on the milk of their cows. Mrs. Hooker was borne through the wilderness upon a litter. The people generally carried their packs, arms, and some utensils. They were nearly a fortnight on their journey.”

Trumbull adds: “This adventure was the more remarkable, as many of this company were persons of figure, who had lived in England in honor, affluence, and delicacy, and were entire strangers to fatigue and danger.” When dismissing these colonists Massachusetts sent with them a governing committee, or commissioners, as they were called. At a meeting of these commissioners, held February 21, 1637, the plantation, which had been called Newtown, was named Hartford. As Governor Haynes was born in the immediate vicinity of the English Hertford, he probably had much influence in naming the new plantation. On the 11th of April, 1639, the first general meeting of the freemen under the constitution was held, and John Haynes was elected the first Governor of Connecticut. This selection shows his active sympathy and co-operation with Hooker, and we can entirely agree with Bancroft, when he says: “They who judge of men by their services to the human race will never cease to honor the memory of Hooker, and of Haynes.”

But the soil of Hartford has had other occupants; not only the aboriginal owners of the soil, for when the English came they found a Dutch trading-post established on what is yet known as Dutch Point. The English claimed the territory now comprehended in the State of Connecticut by virtue of the discoveries of John and Sebastian Cabot in 1497, and more especially in 1498. This territory was included in the grant to the Plymouth Company in 1606, but that organization undertook no work of colonization. When the settlers of 1635 came they took possession of this portion of the valley of the Connecticut under the English flag, and claimed the territory by virtue of patents from the English crown. They paid Sequassen, the Indian chief, who ruled the river Indians, for his lands, and when the Pequots, his over-lords, disputed Sequassen’s right to sell, the colonists attacked them, and practically exterminated the tribe. The Dutch settlement originated from discoveries by Adrian Block, who sailed through the Sound in 1614, and up the Connecticut, or Fresh River, as he called it, in his sloop, The Unrest, as far as the falls, and upon his report to the States-general, a company was formed for trading in the New Netherlands. Only limited privileges were granted to this company, and it was afterwards superseded by the Dutch West India Company, to whom the exclusive governmental and commercial rights for the territory were granted. The Dutch were influenced much more by the desire for a lucrative trade with the natives than by any wish to found a colony, and in 1633 they built a fort on the spot still called Dutch Point, in Hartford, for the purpose of protecting their traffic with the Indians, which they had been carrying on for some ten years. This fort was known as the House of Hope, and when the English came they settled all about it, but did not interfere with the Dutch occupation. Naturally, there was friction between the two nationalities, and petty trespasses of various kinds were charged by both parties. Finally, after repeated complaints, the Commissioners of the United Colonies, Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven, met at Hartford, September 11, 1650, with Peter Stuyvesant, Director of the New Netherlands, to consult upon the proper boundaries of the Dutch jurisdiction. The matter was referred to arbitrators, and resulted in a transfer to the English of all the territory lying west of the Connecticut except the land in Hartford actually occupied by the Dutch, the New Netherlands taking the country east of the river. But this arrangement did not last long, as, in 1653, war was declared between England and Holland, and the colonies were required by Parliament to treat the Dutch as the declared enemies of the Commonwealth of England. Trumbull says:

“In conformity to this order the General Court was convened, and an act passed sequestering the Dutch house, lands, and property of all kinds at Hartford, for the benefit of the Commonwealth; and the Court also prohibited all persons, whatsoever, from improving the premises by virtue of any former claim or title had, made, or given, by any of the Dutch nation, or any other person, without their approbation.”

Even after this change of rulers a few of the Dutch traders remained in Hartford, as is shown by references to them on the records, but they all finally returned to the New Netherlands.

During the next thirty years the little settlement on the banks of the Connecticut continued to grow and prosper, having very little to do with the affairs of the outside world. In 1675 and 1676, King Philip’s War caused great alarm and anxiety for a time, but after this conflict was concluded by the subjugation of the Indians, peace and quietness again reigned. Soon after the accession of James II., in 1685, this quiet was however rudely disturbed by the issue of a writ of quo warranto against the Governor and Company of Connecticut, summoning them to appear before his Majesty, and show by what warrant they exercised certain powers. In reply, the Colony pleaded the Charter, granted by the King’s royal brother, made strong professions of their loyalty, and begged a continuance of their privileges. Two more writs of quo warranto were issued against Connecticut, but she still refused to surrender her Charter, and re-elected Robert Treat as Governor. The Charter of Massachusetts had been vacated, and Chalmers, in his History of the American Colonies, says that “Rhode Island and Connecticut were two little republics embosomed in a great empire.” Rhode Island, however, submitted to his Majesty, so Connecticut stood alone in refusing to surrender her Charter. In the latter part of 1686, Sir Edmund Andros arrived in Boston, bearing his royal commission as Governor of New England. After some correspondence with Governor Treat, who still stood firm, he left Boston for Hartford, with several members of his Council and a small troop of horse. When he arrived in Hartford, October 31, 1687, he was escorted by the Hartford County Troop, and met with great courtesy by the Governor and his assistants. Sir Edmund was conducted to the Governor’s seat in the council chamber, and at once demanded the Charter. Trumbull says:

“The tradition is that Governor Treat strongly represented the great expense and hardships of the colonists in planting the country, the blood and treasure which they had expended in defending it, both against the savages and foreigners; to what hardships and dangers he himself had been exposed for that purpose; and that it was like giving up his life now to surrender the patent and privileges so dearly bought, and so long enjoyed. The important affair was debated and kept in suspense until the evening, when the Charter was brought and laid upon the table, where the Assembly were sitting. By this time great numbers of people were assembled, and men sufficiently bold to enterprise whatever might be necessary, or expedient. The lights were instantly extinguished, and one Captain Wadsworth, of Hartford, in the most silent and secret manner carried off the Charter, and secreted it in a large hollow tree, fronting the house of the Honorable Samuel Wyllys, then one of the Magistrates of the Colony. The people appeared all peaceable and orderly. The candles were officiously relighted, but the patent was gone, and no discovery could be made of it, or of the person who had conveyed it away.”