Полная версия

Полная версияHarper's Young People, November 25, 1879

"Nobody can say that of me," said Mrs. Mouse, holding up her nose in the air; and poor Mr. Mouse gave in utterly, and only ventured an occasional snort every now and then, when one of the fifteen babies squeaked more shrilly than usual.

Mrs. Mouse put her babies in the bottle, and they grew up into fine big mice, nearly as big as their father. But these young mice were very noisy; they tore about, and squeaked even in broad daylight, so that the cross maid looked crosser, and at last told her mistress.

"Them mice are not to be borne, mum, and I'll set a trap."

The old lady said she would not have a trap set, and the dear little things killed, so for some days the mice continued to squeak and scamper as much as ever. But the maid, thinking matters were going too far, got the trap, without saying anything to her mistress, and putting some toasted cheese in it, set it under the wardrobe.

Vainly did Mr. and Mrs. Mouse say to their children, in the most solemn tones, "Don't go near that cage; I don't quite know what it is, but I'm sure it is dangerous." The young ones did not mind them. They thought they would only go and look at it, and then the toasted cheese smelled so very good, it could do no harm just to try and taste it; and so five of them were caught, and next morning were given to the cat.

All the other brothers and sisters went into deep mourning, and could be seen wiping their eyes with their tails a great many times during the following days. Then one or two of them thought change of air would be the best thing for them, so they went down stairs for a short time, and when they came back, to Mr. Mouse's disgust, they each brought back a wife or a husband.

Mr. Mouse was quite angry at such an addition to a family already too large, he thought; so that evening, instead of staying quietly at home, and watching the young ones run races, he was so disturbed in his mind that he went out for a walk.

The moonlight was coming in through the window and making a long line of light on the floor as Mr. Mouse slowly walked out from under the wardrobe. He stood for some time looking about him, thinking in which direction should he first go. His bright little eyes twinkled in the moonlight as he looked this way and that, and having made up his mind to go first to the bird-cage and see how the provisions were there, he sat down on the floor and scratched his ear slowly with his hind-foot. The birds were all asleep on their perches; but to Mr. Mouse's indignation he found that his children, not satisfied with taking all the seed that fell outside, had all but emptied the box in the cage.

"Young scamps," said Mr. Mouse, "they will be getting us into mischief if they eat up everything like this."

From the bird-cage he went on to the old lady's bed, and after running about there for some time, went to sleep under her pillow. He found it so comfortable and warm that next night he went back to the bed, but before going to sleep under the pillow he thought he would like to see what the old lady's night-cap tasted like. He nibbled and nibbled until he had made a large hole; and then, finding it so amusing and nice, he crept under the clothes, and ate several large round holes in her night-gown. But alas for poor Mr. Mouse! The old lady in her sleep happened to roll over on her side: there was a faint squeak, rather muffled by the bedclothes, and Mr. Mouse's days on this earth were over.

Next morning the old lady said to her maid, "Brown, I wish you would look at my cap; there was something tickling and pressing my head last night, and also my leg." Brown looked, and was horrified at the big hole she found on her mistress's cap; but she was speechless when on looking into the bed she found Mr. Mouse's dead body, and two more holes in her mistress's night-gown. She wanted to get a dog or a cat, and any amount of traps; but the old lady was so sorry for the mouse she had killed that she made the excuse that perhaps he was the only one left, and that they would wait a little longer and see. Brown gave in, as she could not help it, and looked crosser than ever on account of the mice.

Now the young Mrs. Mice were searching for homes for their babies, which had come. They could find no place at all, until one day one of them found a hole in the back of the wardrobe, and calling her sister, they both with great caution crept in and found just what they wanted. One of them took possession of the old lady's bonnet, one of the old-fashioned big ones, all quilted with satin inside; and the other the muff to match the bonnet. There could not have been more comfortable nests for their babies, when the linings were removed and had all been properly cut up into shreds, than the old lady's muff and bonnet made; so the two young mammas were in high delight, and tucked their babies in that night, feeling they had been wiser and luckier than any Mrs. Mouse ever had been in getting such a bed for their little ones.

A few days after a young lady came running into the room. She was a very pretty young lady, and she seemed to bring sunshine and happiness into the room with her. "Oh, grandmamma!" she cried, "you must put on your things and come out. I have brought the carriage for you; the sun is shining so brightly; the wind is from the south, and it is quite summer. It will do you so much good to get some fresh air."

"Oh, little one, I could not," said grandmamma; "I have not been out for months, and I don't know where my things are. I don't think I can go out to-day. It does me almost as much good to see your bright face."

"You must come out, grandmamma; it's no use making excuses," said the young lady; and so the old lady gave in, as everybody did to this sunshiny little woman.

As soon as the two young Mrs. Mice heard the doors of the wardrobe opened, they scampered away as fast as they could. The bonnet was taken out, and then the muff, and you can think what a scene there was when the nasty hairless little mice tumbled out, and they found how utterly destroyed both bonnet and muff were.

That was the last of the Mouse family. The old lady moved into another room the next day. Her old room was cleared of furniture, the mouse-holes stopped up, a cat put in at night, and a bull-terrier by day, and traps of all kinds. Every mouse was killed, and not a single one from any other part of the house had courage to go into that room after such a tragedy.

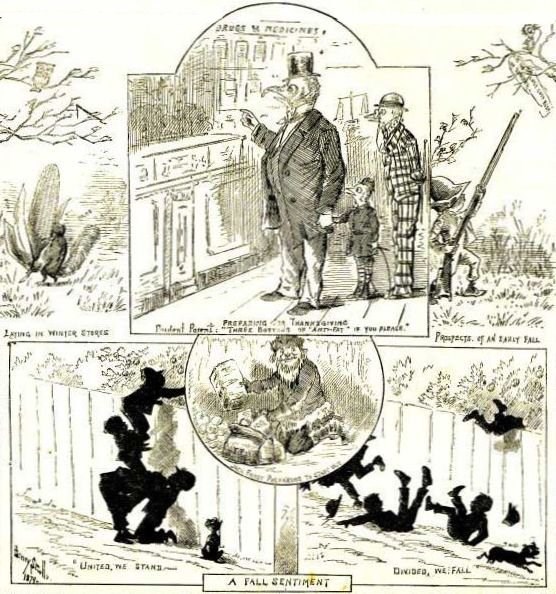

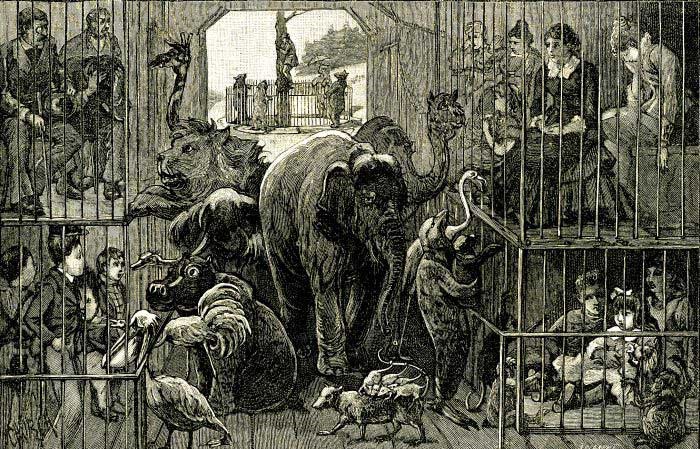

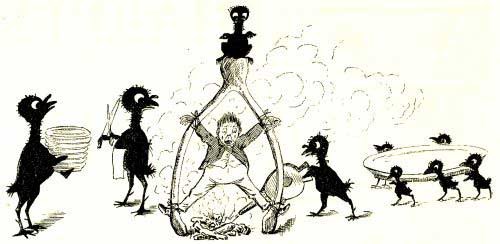

TOO MUCH TURKEY—THE KEEPER'S DREAM.—Drawn by F. S. Church.

The Raven Stone.—In Germany a superstition prevails that if the eggs are taken from a raven's nest, boiled, and replaced, the old raven will bring a root or stone to the nest, which he fetches from the sea. This "raven stone" confers great fortune on its owner, and has the power of rendering him invisible when worn on the arm. The stone is said to make the nest itself invisible; it must be sought with the aid of a mirror. In Pomerania and Rügen the method is somewhat different. The parent birds must have attained the age of one hundred years, and the would-be possessor of the precious "stone" must climb up and kill one of the young ravens. Then the aggressor descends, taking careful note of the tree. The old raven immediately returns with the stone, which he puts in the dead bird's beak, and thereupon both tree and nest become invisible. The man, however, feels for the tree, and on reaching the nest, he carries off the stone in triumph. The Swabian peasantry maintain that young ravens are nourished solely by the dew from heaven during the first nine days of their existence. As they are naked, and of a light color, the old birds do not believe that they are their progeny, and consequently neglect to feed them; but they occasionally cast a glance at the nest, and when the young ones begin to show a little black down on their breasts, by the tenth day, the parents bring them the first carrion.

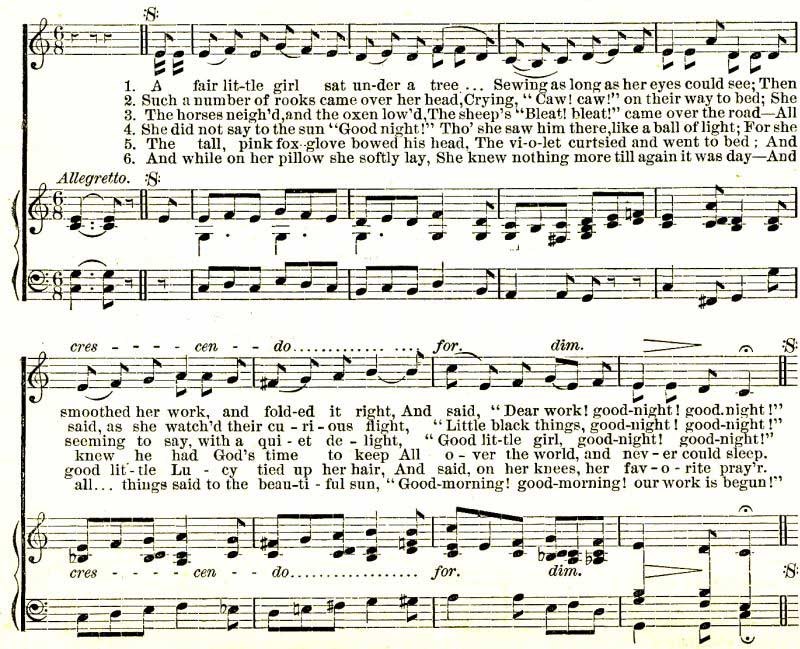

Good-Night and Good-Morning

LETTER FROM A LITTLE GIRL ABOUT "HARPER'S YOUNG PEOPLE."

Newport, Rhode Island, November 6, 1879.

Mr. Editor,—I don't know who to put at the head of this letter, because I don't know your first name. I wonder if it is Uncle John.

Papa found me reading what he called a "trash paper" the other day, and he said he would take a good paper for me if I would not read any more of that kind of trash; and he said you was going to print a nice paper for young folks, and this morning he brought one home—the very first number; but he said he was disappointed in the size of it, and that it was not quite half so big as an ordinary paper at four cents, and I am afraid he will not take it for me; but mamma says if I wrote to you perhaps you could give me some good reason for the paper being smaller than papa expected, so that he will keep his promise, for I like the paper very much, and I have read about the "Brave Swiss Boy," and so has father; and he says it is better than the kind of paper they throw in the door—"to be continued." So please tell us why your paper is not so big as the "trash papers," as father calls them, and I will be very thankful.

Lizzie M. D.There are several reasons why Harper's Young People is not as large as the journals which you call "trash" papers. In the first place, Harper's Young People is very carefully printed on extra fine paper, which make the type and illustrations look so clear and beautiful. And then a very large price is paid to the artists who draw the pictures, to the engravers who reproduce them on wood, and to the authors who contribute the reading matter which you find so interesting. The picture of "The Tournament," for instance, on the first page of the preceding number, cost over one hundred and fifty dollars for drawing and engraving. Some of the pictures will cost even more than that. If Young People was a larger weekly paper, and just as good in every respect as it is now, the price would necessarily be larger; and then some of our young readers might be deprived of the pleasure of having it.

Harper's Young People comes out every Tuesday; and if you read all the stories, poems, etc., and make out the puzzles and enigmas, you will find that it will take all the time you ought to spare from study, play, and other callings. We mean to make Young People the very best weekly for children in the world, so that they will always be glad to see it, as they would welcome a visit from a pleasant companion.

The following letters have been received in reply to the question, in the first number of Young People, as to the originator of cheap postage.

New York City.

The founder of the system of prepaying postage by placing a small label on one corner of the letter was Sir Rowland Hill. It was first advocated by him in 1837, and stamps were first used by the British Post-office May 6, 1840. They were introduced in the United States in 1847. Sir Rowland was born at Kidderminster in 1795, and died at Hampstead August 27, 1879, at the age of eighty-four.

Walter J. Lee.Brooklyn, New York.

In answer to your question in the first number of Young People, asking if any one knew the name of the man who first thought of cheap postage, I would say that it was Sir Rowland Hill, of England. He died a few months ago at Hampstead, near London, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

The answer to your letter puzzle in the same number is "Longfellow."

F. B. Hesse (11 years old).Clara S. Gardiner, St. Louis, Missouri, sends a similar reply.

Correct answers to letter puzzle have also been received from Albert E. Seibert, New York city, and Annie B. Stephens, Elizabeth, New Jersey. Several correct answers to the mathematical puzzles have been sent in, and will be published as soon as other correspondents have had time to try their skill.

Louis B. Parsons, Montclair, New Jersey.—If you will put a very little oil of cloves, or still better, a few drops of creosote, into your ink, it will not trouble you by moulding. You should also keep it corked tight when not in use.

THE STORY OF A PARROT

I soon heard the sound of voices, and in a moment my mistress with the children entered the room. I greeted them with screams and laughter, while the whole party stopped in astonishment at the wrecked condition of the pretty sitting-room.

"Oh, Lorito, you bad, bad boy!" said Louis, shaking his finger at me.

"Oo-oo-oo, bad boy! bad boy!" I screamed, to the great delight of the children, who forgot in an instant the mischief I had done, and began to laugh heartily. Seeing my advantage, I kept up a constant rattle of all the ridiculous nonsense I knew. The wine was still dancing in my head, and I made a very sorrowful exhibition of myself.

The children's mother soon discovered the empty bowl lying tipped over on the hearth.

"Poor Lorito is drunk," she said, laughing; "he has swallowed every drop of the wine. We must not blame him for his naughty actions. He is only a bird, and has not enough sense to let wine alone."

She then began to lament the loss of my beauty. I was indeed a frightful object; and when I heard my mistress declare that if I could not be cleaned I must be turned out of the house, my terror at the thought of losing what I had begun to realize was a comfortable home brought me to my sober senses at once. I hung my head and was silent. For the first time in my life I was mortified and ashamed of myself.

It was now decided to try water on my feathers, and Louis, putting me on his shoulder, carried me to the bath-room. I did feel the greatest inclination to bite his ear, but I contented myself by gently pulling his hair, which made him laugh.

It was a great luxury to get into the bath-tub, for no one had even given me water to wet my feet for a very long time; and although parrots do not care to get in the tub every morning and flutter and spatter like canaries, still they like to wet their feet, and, above all things, they enjoy a gentle shower-bath, like a summer rain.

I can not say the bath the children gave me was what I would have chosen myself, for they rubbed me and scrubbed me and tumbled me about till I was half dead. At last it was over. The ink stains had nearly disappeared from my feathers, but I was cold and miserable. Then, too, I had proved myself such a destructive personage when free that my feet were chained once more; and although my mistress had kindly covered the rings I wore round my ankles with soft flannel, the chain was still a dreadful burden. When I was at last left alone on my perch, I gave way to the most sorrowful meditations.

Still, all my present happiness dates from that troublesome time. The children were with me constantly, and their kind treatment completely cured me of my ugly, malicious temper. I then became acquainted with my dear friend Fritz, in whose company I have spent many happy hours. In order to talk with him I was compelled to learn his language, and soon I could bark so well that little Hope would clap her hands and say, "Our Rito makes a better doggie than Fritz himself."

"FRITZ ADORED SUGAR."

Often when I sat on my perch Fritz would lie on the carpet near me, and we would hold long conversations together. He, too, had met with disappointments in life, and we consoled each other. We shared constantly the good things given us, and I soon discovered that Fritz adored sugar. As there were always some pieces in my feed dish, I kept them for him, and many a frolic we have had, for I never could help tantalizing him by holding the tempting morsel higher than he could jump.

I have had some nice friends in the garden, for in warm weather I was often carried out and placed on the branch of a tree, where I had the companionship of butterflies and bees and many kinds of birds. Although they were neither so large nor so beautiful in color as those I knew in my childhood on the banks of the Congo, still I found them excellent company. I would have been perfectly happy in the garden had it not been for the chain which fastened me to the branch; but experience had made me wiser than formerly, and I had learned not to expect perfect happiness, so I wore my chain patiently.

My feed dish was fastened at my side, and as it was always well filled with sugar, bird seed, and other dainties, I often offered some to my new friends; but so awed were they by my size and grand appearance that they feared to approach me, although they would sit on a neighboring branch and talk to me by the hour. Suddenly an idea occurred to me, which I at once put in practice. Springing from my branch, I hung in the air by my chain, which was not only healthy exercise, but left my feed dish free for my guests. They came in crowds, the sparrows of course, hundreds of them, and also robins and finches. So often was this repeated that, to the great surprise of the children, my feed dish was emptied several times every day.

"Mamma," I heard Carrie say once when they were all in the garden together, "Rito eats like an ogre. I am afraid he'll kill himself."

"The fresh air makes him hungry," said Louis, who always had a wise reason for everything. "The day you went to grandpa's, and played in the hay meadow, you ate like an ogre too. I heard grandma say so."

"Yes, I did eat all the jumbles in grandma's tin cake-box," said Carrie; "but that was only once, and every day nurse has to fill Rito's feed dish seven or eight times. He eats enough for ten Ritos."

"Oh, mamma, look at him!" screamed little Hope, who at that moment spied me indulging in my favorite exercise, swinging back and forth on my chain. The children and their mother ran toward me, while I, with one of my loud laughs (which I have heard some people say was a very wicked laugh: I don't think so), skillfully swung myself back to my branch, frightening as I did it a crowd of my feathered friends who were gathered about my feed dish. The children's mother saw them fly away. "Look," she cried; "there go the ogres. It is those thieving sparrows who eat so much, and not Lorito himself."

Now the sparrows may be too bold sometimes, but I do not think they are thieves, and it made me very angry to hear them called such a bad name. I screamed and struck my wings together so violently that I slipped from the branch, and was again swinging in the air by my chain.

"Mamma, Rito will break his legs, and then we shall have to kill him," screamed Louis, in alarm.

"Take off his chain, oh, mamma, do," said kind-hearted Carrie; while little Hope pleaded in her sweet voice: "Poor Rito will be good, mamma. He won't bite things any more."

You can not imagine how eagerly I listened to the discussion, for to be free from my chain was now my sole ambition. My heart was touched by the affection of the children, and when, to my intense delight, their mother yielded to their entreaties, I made a firm resolve that I would never bite and tear things again, unless by good luck I could find an old newspaper or a worthless stick, because I knew if I could not use my beak occasionally, it would ache as bad as Carrie's tooth does some nights when she goes crying to bed.

Since that time my life has been very peaceful. I am free as air, my wings have recovered their strength, and I go wherever I please. Whenever my little master Louis whistles for me I answer him at once, for I have learned to whistle as well as he, and I always go as fast as I can to perch upon his hand.

"I GO INTO MY CAGE."

When night comes, and it grows dark, I go into my cage myself, and my good friend Fritz always sleeps near me.

I have not forgotten my dear papa and mamma, nor my brother and sister, and I often wonder if they are still living in the beautiful hollow tree by the Congo; but I have learned to love new things, and to remember my childhood as a sweet dream instead of a lost and longed-for reality.

The gray parrot gave a little soft laugh, and was silent.

"I declare," said the canary, who had listened very attentively, "you have seen a lot of trouble. But why such a quiet, gentlemanly bird as you should have such a passion to bite and tear things, I can't imagine. Now my family—" But what the canary had to tell will always be a mystery, for at that moment the door opened and in came papa and mamma from the party.

"Oh, Fritz, you naughty dog!" said mamma, when she saw her pretty afghan lying in a heap on the floor. But when she lifted it to put it back on the lounge, she found Louis, still hugging his bow and arrow, Carrie, Hope, the white kitty, and Fritz, all curled up in a little warm bunch, sound asleep.

At that moment nurse, who had just returned from her party too, came running down stairs in great alarm.

"Sure, ma'am, the children ain't in their beds at all," she began, but stopped in astonishment when she saw her little charges sitting on the rug, rubbing their fists into their sleepy eyes.

"They did talk," said Louis, as soon as he was wide-awake enough to speak. "Lorito told us all about his brother and sister and everybody."

"Yes, mamma, and he's so sorry he tipped over the ink," said Carrie.

"Good Rito loves me," said little Hope; "he wouldn't bite me for anything;" and she hugged her white kitty, and went fast asleep, with her little head on mamma's shoulder, while mamma laughed merrily at the children's wonderful dream.

The gray parrot did not say a word. He sat very quiet in his cage, his head buried in his feathers, and his eyes shut tight.

But if, as mamma said, the children had been dreaming, it was very funny indeed that they all three dreamed exactly the same thing.

the end

A GREEDY BOY'S THANKSGIVING DREAM.

Relative Age of Animals.—The average age of cats is 15 years; of squirrels and hares, 7 or 8 years; rabbits, 7; a bear rarely exceeds 20 years; a dog lives 20 years, a wolf 20, a fox 14 to 16; lions are long-lived, the one known by the name of Pompey living to the age of 70. Elephants have been known to live to the age of 400 years. When Alexander the Great had conquered Porus, King of India, he took a great elephant which had fought valiantly for the king, and named him Ajax, dedicated him to the sun, and let him go with this inscription, "Alexander, the son of Jupiter, dedicated Ajax to the sun." The elephant was found with this inscription 350 years after. Pigs have been known to live to the age of 20, and the rhinoceros to 29; a horse has been known to live to the age of 62, but they average 25 or 30; camels sometimes live to the age of 100; stags are very long-lived; sheep seldom exceed the age of 10; cows live about 15 years. Cuvier considers it probable that whales sometimes live 1000 years. The dolphin and porpoise attain the age of 30; an eagle died at Vienna at the age of 104; ravens have frequently reached the age of 100; swans have been known to live to the age of 300. Mr. Malerton has the skeleton of a swan that attained the age of 200 years. Pelicans are long-lived. A tortoise has been known to live to the age of 107 years.

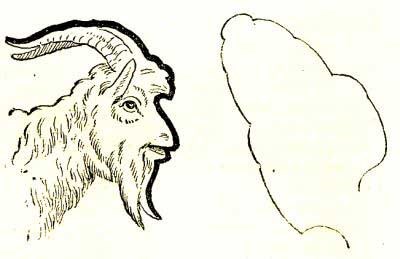

WIGGLES

The thick black line in this picture is a facsimile of the line No. 6 in our last Wiggles, which we submitted to our readers, on which to test their ingenuity.

We subjoin another Wiggle, and shall be happy to see what our young friends can do with it.