Полная версия

Полная версияHarper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol. IV, No. 19, Dec 1851

Doesn't the impressive inquiry embodied in the ensuing touching lines, somewhat enter into the matrimonial thoughts of some of our city "offerers?"

"Oh! do not paint her charms to me,I know that she is fair!I know her lips might tempt the bee,Her eyes with stars compare:Such transient gifts I ne'er could prize,My heart they could not win:I do not scorn my Mary's eyes,But – has she any 'tin?'"The fairest cheek, alas! may fade,Beneath the touch of years;The eyes where light and gladness played,May soon grow dim with tears:I would love's fires should to the lastStill burn, as they begin;But beauty's reign too soon is past;So – has she any 'tin?'"There is something very touching and pathetic in a circumstance mentioned to us a night or two ago, in the sick-room of a friend. A poor little girl, a cripple, and deformed from her birth, was seized with a disorder which threatened to remove her from a world where she had suffered so much. She was a very affectionate child, and no word of complaining had ever passed her lips. Sometimes the tears would come in her eyes, when she saw, in the presence of children more physically blessed than herself, the severity of her deprivation, but that was all. She was so gentle, so considerate of giving pain, and so desirous to please all around her, that she had endeared herself to every member of her family, and to all who knew her.

At length it was seen, so rapid had been the progress of her disease, that she could not long survive. She grew worse and worse, until one night, in an interval of pain, she called her mother to her bed-side, and said, "Mother, I am dying now. I hope I shall see you, and my brother and sisters in Heaven. Won't I be straight, and not a cripple, mother, when I do get to Heaven?" And so the poor little sorrowing child passed forever away.

"I heard something a moment ago," writes a correspondent in a Southern city, "which I will give you the skeleton of. It made me laugh not a little; for it struck me, that it disclosed a transfer of 'Yankee Tricks' to the other side of the Atlantic. It would appear, that a traveler stopped at Brussels, in a post-chaise, and being a little sharp-set, he was anxious to buy a piece of cherry-pie, before his vehicle should set out; but he was afraid to leave the public conveyance, lest it might drive off and leave him. So, calling a lad to him from the other side of the street, he gave him a piece of money, and requested him to go to a restaurant or confectionery, in the near vicinity, and purchase the pastry; and then, to 'make assurance doubly sure,' he gave him another piece of money, and told him to buy some for himself at the same time. The lad went off on a run, and in a little while came back, eating a piece of pie, and looking very complacent and happy. Walking up to the window of the post-chaise, he said, with the most perfect nonchalance, returning at the same time one of the pieces of money which had been given him by the gentleman, 'The restaurateur had only one piece of pie left, and that I bought with my money, that you gave me!'"

This anecdote, which we are assured is strictly true, is not unlike one, equally authentic, which had its origin in an Eastern city. A mechanic, who had sent a bill for some article to a not very conscientious pay-master in the neighborhood, finding no returns, at length "gave it up as a bad job." A lucky thought, however, struck him one day, as he sat in the door of his shop, and saw a debt-collector going by, who was notorious for sticking to a delinquent until some result was obtained. The creditor called the collector in, told him the circumstances, handed him the account, and added:

"Now, if you will collect that debt, I'll give you half of it; or, if you don't collect but half of the bill, I'll divide that with you."

The collector took the bill, and said, "I guess, I can get half of it, any how. At any rate, if I don't, it shan't be for want of trying hard enough."

Nothing more was seen of the collector for some five or six months; until one day the creditor thought he saw "the indefatigable" trying to avoid him by turning suddenly down a by-street of the town. "Halloo! Mr. – !" said he; "how about that bill against Mr. Slowpay? Have you collected it yet?" "Not the hull on it, I hain't," said the imperturbable collector; "but I c'lected my half within four weeks a'ter you gin' me the account, and he hain't paid me nothin' since. I tell him, every time I see him, that you want the money very bad; but he don't seem to mind it a bit. He is dreadful 'slow pay,' as you said, when you give me the bill! Good-morning!" And off went the collector, "staying no further question!"

There is a comical blending of the "sentimental" and the "matter-of-fact" in the ensuing lines, which will find a way to the heart of every poor fellow, who, at this inclement season of the year, is in want of a new coat:

By winter's chill the fragrant flower is nipped,To be new-clothed with brighter tints in springThe blasted tree of verdant leaves is stripped,A fresher foliage on each branch to bring.The aerial songster moults his plumerie,To vie in sleekness with each feathered brother.A twelvemonth's wear hath ta'en thy nap from thee,My seedy coat! —when shall I get another?"My name," said a tall, good-looking man, with a decidedly distingué air, as he entered the office of a daily newspaper in a sister city, "my name, Sir, is Page – Ed-w-a-rd Pos-th-el-wa-ite Pa-ge! You have heard of me no doubt. In fact, Sir, I was sent to you, by Mr. C – r, of the ' – Gazette.' I spent some time with him – an hour perhaps – conversing with him. But as I was about explaining to him a little problem which I had had in my mind for some time, I thought I saw that he was busy, and couldn't hear me. In fact, he said, 'I wish you would do me the kindness to go now and come again; and always send up your name, so that I may know that it is you; otherwise,' said he, 'I shouldn't know that it was you, and might refuse you without knowing it.' Now, Sir, that was kind – that was kind, and gentlemanly, and I shall remember it. Then he told me to come to see you; he said yours was an afternoon paper, and that your paper for to-day was out, while he was engaged in getting his ready for the morning. He rose, Sir, and saw me to the door; and downstairs; in fact, Sir, he came with me to the corner, and showed me your office; and for fear I should miss my way, he gave a lad a sixpence, to show me here, Sir.

"They call me crazy, Sir, some people do —crazy! The reason is simple – I'm above their comprehension. Do I seem crazy? I am an educated man, my conduct has been unexceptionable. I've wronged no man – never did a man an injury. I wouldn't do it.

"I came to America in 1829 2^m which being multiplied by Cæsar's co-sine, which is C B to Q equal X' 3^m."

Yes, reader; this was Page, the Monomaniac: a man perfectly sound on any subject, and capable of conversing upon any topic, intelligently and rationally, until it so happened, in the course of conversation, that he mentioned any numerical figure, when his wild imagination was off at a tangent, and he became suddenly as "mad as a March hare" on one subject. Here his monomania was complete. In every thing else, there was no incoherency; nothing in his speech or manner that any gentleman might not either say or do. So much for the man: now for a condensed exhibition of his peculiar idiosyncrasy, as exhibited in a paper which he published, devoted to an elaborate illustration of the great extent to which he carried the science of mathematics. The fragments of various knowledge, like the tumbling objects in a kaleidoscope, are so jumbled together, that we defy any philosopher, astronomer, or mathematician, to read it without roaring with laughter; for the feeling of the ridiculous will overcome the sensations of sympathy and pity. But listen: "Here's 'wisdom' for you," as Captain Cuttle would say: intense wisdom:

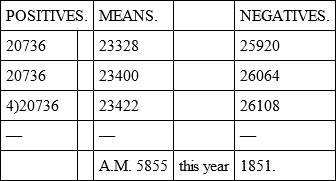

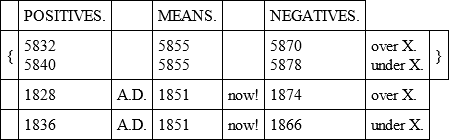

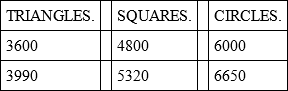

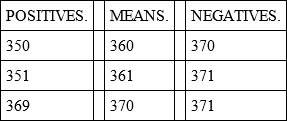

"Squares are to circles as Miss Sarai 18 when she did wed her Abram 20 on Procrustes' bed, and 19 parted between each head; so Sarah when 90 to Abraham when 100, and so 18 squared in 324, a square to circle 18 × 20 = 360, a square to circle 400, a square to circle 444, or half Jesous 888 in half the Yankee era 1776; which 888 is sustained by the early Fathers and Blondel on the Sibyls. It is a square to triangle Sherwood's no-variation circle 666 in the sequel. But 19 squared is 361 between 360 and 362, each of which multiply by the Sun's magic compass 36, Franklin's magic circle of circles 360 × 36 considered.

"Squares are to circles as 18 to 20, or 18 squared in 324 to 18 × 20 = 360. But more exactly as 17 to 19, or 324 to 362 × 36, or half 26064. As 9 to 10, so square 234000 to circle 26000.

"Squares are to circles as 17 to 19, or 23360 to 26108. The sequel's 5832 and 5840 are quadrants of 23328 and 23360.

"18 cubed is 5832, the world's age in 1828, 5840 its age in the Halley comet year 1836, 5878 its age the next transit of Venus in 1874, but 5870 is its age in the prophet's year 1866.

"100 times the Saros 18 = 18-1/2 = 19 in 1800 last year's 1850, 1900 for new moons.

"If 360 degrees, each 18, in Guy's 6480, evidently 360 × 18-1/2 in the adorable 6660, or ten no-variation circles, each 36 × 18-1/2 = 666, like ten Chaldee solar cycles, each 600 in our great theme, 6000, the second advent date of Messiah, as explained by Barnabas, Chap. xiii in the Apocryphal New Testament, 600 and 666 being square and circle, like 5994 and 6660. Therefore 5995 sum the Arabic 28, or Persic 32, or Turkish 33 letters.

"But as 9 to 10, so square 1665 of the Latin IVXLCDM = 1666 to circle last year's 1850 – 12 such signs are as much 19980 and 22200, whose quadrants are 4995 and 5550, as 12 signs, each the Halley comet year 1836, are 5508 Olympiads, the Greek Church claiming this era 5508 for Christ.

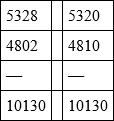

"But though the ecliptic angle has decreased only 40 × 40 in 1600 during 43 × 43 = 1849, say 1850 from the birth of Christ, and double that since the creation; yet 1600 and Yankee era 1776 being square and circle like 9 and 10 – place 32 for a round of the seasons in a compass of 32 points, or shrine them in 32 chessmen, like 1600 and 1600 in each of 16 pieces; then shall 32 times Sherwood's no-variation circle 666, meaning 666 rounds of the seasons, each 32, be 12 signs, each 1776, or 24 degrees in the ecliptic angle, each Jesous 888, in circle 21312 to square 19200, or 12 signs each 1600, that the quadrants of square 19200 and circle 21312 may be the Cherubim of Glory 4800 and 5328; which explains ten Great Paschal cycles each 532, a square to circle 665 of the Beast's number 666. Because, like 3, 4, 5, in my Urim and Thummim's 12 jewels, are

"Because 3990 of the Latin Church's era 4000 for Christ, is doubled in the Julian period 7980.

"Every knight of the queen of night may know that each of 9 columns in the Moon's magic compass for 9 squared in 81, sums 369, and that 370 are between it and 371, while 19 times 18-1/2 approach 351, when 19 squared are 361 in

"The Saros 18 times 369 in 6642 of the above 6650; but 18 × 370 = 6660, or 360 times 18-1/2.

"1800 and proemptosis 2400 are half this Seraphim 3600 and Cherubim 4800: but 7 × 7 × 49 × 49 = 2401 in 4802.

"All that Homer's Iliad ever meant, was this: 10 years as degrees on Ahaz's dial between the positive 4790, mean 4800, negative 4810: If the Septuagints' 72 times 90 in 360 × 18 = 6480, equally 72 times 24 and 66 degrees in 12 cubed and 4752."

Now it is about enough to make one crazy to read this over; and yet it is impossible not to see, as it is impossible not to laugh at the transient glimpses of scattered knowledge which the singular ollapodrida contains.

"If you regard, Mr. Editor, the following," says a city friend, "as worthy a place in your 'Drawer,' you are perfectly welcome to it. It was an actual occurrence, and its authenticity is beyond a question:

"Many years ago, when sloops were substituted for steamboats on the Hudson River, a celebrated Divine was on his way to hold forth to the inhabitants of a certain village, not many miles from New York. One of his fellow-passengers who was an unsophisticated countryman, to make himself appear 'large' in the eyes of the passengers, entered into a conversation with the learned Doctor of Divinity. After several ordinary remarks, and introducing himself as one of the congregation, to whom he (the doctor) would expound the Word on the morrow, the following conversation took place:

"'Wal, Doctor, I reckon you know the Scripters pooty good,' remarked the countryman.

"'Really, my friend,' said the clergyman, 'I leave that for other persons to determine. You know it does not become a person of any delicacy to utter praise in his own behalf.'

"'So it doesn't,' replied the querist; 'but I've heerd folks say, you know rather more than we do. They say you're pooty good in larning folks the Bible: but I guess I can give you a poser.'

"'I am pleased to answer questions, and feel gratified to tender information at any time, always considering it my duty to impart instruction, as far as it lies in my power,' replied the clergyman.

"'Wall,' says the countryman, with all the imperturbable gravity in the world, 'I spose you've heerd tell on, in the Big Book, 'bout Aaron and the golden calf: now, in your opinion, do you think the calf Aaron worshiped, was a heifer or a bull?'

"The Doctor of Divinity, as may be imagined, immediately 'vamosed,' and left the countryman bragging to the by-standers, that he had completely nonplussed the clergyman!"

Literary Notices

A new work by Herman Melville, entitled Moby Dick; or, The Whale, has just been issued by Harper and Brothers, which, in point of richness and variety of incident, originality of conception, and splendor of description, surpasses any of the former productions of this highly successful author. Moby Dick is the name of an old White Whale; half fish and half devil; the terror of the Nantucket cruisers; the scourge of distant oceans; leading an invulnerable, charmed life; the subject of many grim and ghostly traditions. This huge sea monster has a conflict with one Captain Ahab; the veteran Nantucket salt comes off second best; not only loses a leg in the affray, but receives a twist in the brain; becomes the victim of a deep, cunning monomania; believes himself predestined to take a bloody revenge on his fearful enemy; pursues him with fierce demoniac energy of purpose; and at last perishes in the dreadful fight, just as he deems that he has reached the goal of his frantic passion. On this slight framework, the author has constructed a romance, a tragedy, and a natural history, not without numerous gratuitous suggestions on psychology, ethics, and theology. Beneath the whole story, the subtle, imaginative reader may perhaps find a pregnant allegory, intended to illustrate the mystery of human life. Certain it is that the rapid, pointed hints which are often thrown out, with the keenness and velocity of a harpoon, penetrate deep into the heart of things, showing that the genius of the author for moral analysis is scarcely surpassed by his wizard power of description.

In the course of the narrative the habits of the whale are fully and ably described. Frequent graphic and instructive sketches of the fishery, of sea-life in a whaling vessel, and of the manners and customs of strange nations are interspersed with excellent artistic effect among the thrilling scenes of the story. The various processes of procuring oil are explained with the minute, painstaking fidelity of a statistical record, contrasting strangely with the weird, phantom-like character of the plot, and of some of the leading personages, who present a no less unearthly appearance than the witches in Macbeth. These sudden and decided transitions form a striking feature of the volume. Difficult of management, in the highest degree, they are wrought with consummate skill. To a less gifted author, they would inevitably have proved fatal. He has not only deftly avoided their dangers, but made them an element of great power. They constantly pique the attention of the reader, keeping curiosity alive, and presenting the combined charm of surprise and alternation.

The introductory chapters of the volume, containing sketches of life in the great marts of Whalingdom, New Bedford and Nantucket, are pervaded with a fine vein of comic humor, and reveal a succession of portraitures, in which the lineaments of nature shine forth, through a good deal of perverse, intentional exaggeration. To many readers, these will prove the most interesting portions of the work. Nothing can be better than the description of the owners of the vessel, Captain Peleg and Captain Bildad, whose acquaintance we make before the commencement of the voyage. The character of Captain Ahab also opens upon us with wonderful power. He exercises a wild, bewildering fascination by his dark and mysterious nature, which is not at all diminished when we obtain a clearer insight into his strange history. Indeed, all the members of the ship's company, the three mates, Starbuck, Stubbs, and Flash, the wild, savage Gayheader, the case-hardened old blacksmith, to say nothing of the pearl of a New Zealand harpooner, the bosom friend of the narrator – all stand before us in the strongest individual relief, presenting a unique picture gallery, which every artist must despair of rivaling.

The plot becomes more intense and tragic, as it approaches toward the denouement. The malicious old Moby Dick, after long cruisings in pursuit of him, is at length discovered. He comes up to the battle, like an army with banners. He seems inspired with the same fierce, inveterate cunning with which Captain Ahab has followed the traces of his mortal foe. The fight is described in letters of blood. It is easy to foresee which will be the victor in such a contest. We need not say that the ill-omened ship is broken in fragments by the wrath of the weltering fiend. Captain Ahab becomes the prey of his intended victim. The crew perish. One alone escapes to tell the tale. Moby Dick disappears unscathed, and for aught we know, is the same "delicate monster," whose power in destroying another ship is just announced from Panama.

G. P. Putnam announces the Home Cyclopedia, a series of works in the various branches of knowledge, including history, literature, and the fine arts, biography, geography, science, and the useful arts, to be comprised in six large duodecimos. Of this series have recently appeared The Hand-book of Literature and the Fine Arts, edited by George Ripley and Bayard Taylor, and The Hand-book of Universal Biography, by Parke Godwin. The plan of the Encyclopedia is excellent, adapted to the wants of the American people, and suited to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge. As a collateral aid in a methodical course of study, and a work of reference in the daily reading, which enters so largely into the habits of our countrymen, it will, no doubt, prove of great utility.

Rural Homes, by Gervasse Wheeler (published by Charles Scribner), is intended to aid persons proposing to build, in the construction of houses suited to American country life. The author writes like a man of sense, culture, and taste. He is evidently an ardent admirer of John Ruskin, and has caught something of his æsthetic spirit. Not that he deals in mere theories. His book is eminently practical. He is familiar with the details of his subject, and sets them forth with great simplicity and directness. No one about to establish a rural homestead should neglect consulting its instructive pages.

Ticknor, Reed, and Fields have published a new work, by Nathaniel Hawthorne, for juvenile readers, entitled A Wonder-Book for Boys and Girls with engravings by Barker from designs by Billings. It is founded on various old classical legends, but they are so ingeniously wrought over and stamped with the individuality of the author, as to exercise the effect of original productions. Mr. Hawthorne never writes more genially and agreeably than when attempting to amuse children. He seems to find a welcome relief in their inartificial ways from his own weird and sombre fancies. Watching their frisky gambols and odd humors, he half forgets the saturnine moods from which he draws the materials of his most effective fictions, and becomes himself a child. A vein of airy gayety runs through the present volume, revealing a sunny and beautiful side of the author's nature, and forming a delightful contrast to the stern, though irresistibly fascinating horrors, which he wields with such terrific mastery in his recent productions. Child and man will love this work equally well. Its character may be compared to the honey with which the author crowns the miraculous hoard of Baucis and Philemon. "But oh the honey! I may just as well let it alone, without trying to describe how exquisitely it smelt and looked. Its color was that of the purest and most transparent gold; and it had the odor of a thousand flowers; but of such flowers as never grew in an earthly garden, and to seek which the bees must have flown high above the clouds. Never was such honey tasted, seen, or smelt. The perfume floated around the kitchen, and made it so delightful, that had you closed your eyes you would instantly have forgotten the low ceiling and smoky walls, and have fancied yourself in an arbor with celestial honeysuckles creeping over it."

Glances at Europe, by Horace Greeley (published by Dewitt and Davenport), has passed rapidly to a second edition, being eagerly called for by the numerous admirers of the author in his capacity as public journalist. Composed in the excitement of a hurried European tour, aiming at accuracy of detail rather than at nicety of language, intended for the mass of intelligent readers rather than for the denizens of libraries, these letters make no claim to profound speculation or to a high degree of literary finish. They are plain, straight-forward, matter-of-fact statements of what the writer saw and heard in the course of his travels, recording at night the impressions made in the day, without reference to the opinions or descriptions of previous travelers. The information concerning various European countries, with which they abound, is substantial and instructive; often connected with topics seldom noticed by tourists; and conveyed in a fresh and lively style. With the reputation of the author for acute observation and forcible expression, this volume is bound to circulate widely among the people.

Ticknor, Reed, and Fields, have issued a new volume of Poems, by Richard Henry Stoddard, consisting of a collection of pieces which have been before published, and several which here make their appearance for the first time. It will serve to elevate the already brilliant reputation of the youthful author. His vocation to poetry is clearly stamped on his productions. Combining great spontaneity of feeling, with careful and elaborate composition, he not only shows a native instinct of verse, but a lofty ideal of poetry as an art. He has entered the path which will lead to genuine and lofty fame. The success of his early effusions has not elated him with a vain conceit of his own genius. Hence, we look for still more admirable productions than any contained in the present volume. He is evidently destined to grow, and we have full faith in the fulfillment of his destiny. His fancy is rich in images of gorgeous and delicate beauty; a deep vein of reflection underlies his boldest excursions; and on themes of tender and pathetic interest, his words murmur with a plaintive melody that reaches the hidden source of tears. His style, no doubt, betrays the influence of frequent communings with his favorite poets. He is eminently susceptible and receptive. He does not wander in the spicy groves of poetical enchantment, without bearing away sweet odors. But this is no impeachment of his own individuality. He is not only drawn by the subtle affinities of genius to the study of the best models, but all the impressions which he receives, take a new form from his own plastic nature. The longest poem in the volume is entitled, "The Castle in the Air" – a production of rare magnificence. "The Hymn to Flora," is full of exquisite beauties, showing a masterly skill in the poetical application of classical legends. "Harley River," "The Blacksmith's Shop," "The Old Elm," are sweet rural pictures, soft and glowing as a June meadow in sunset. "The Household Dirge," and several of the "Songs and Sonnets," are marked by a depth of tenderness which is too earnest for any language but that of the most severe simplicity.