Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Essays in Liberalism

The Appeal to Public Opinion

There is something more. There is something wanted from each of us. Personally, I am convinced myself that this problem is soluble on the lines by which it is now being approached. I speak to you as a professional who has given some study to the subject. I am convinced that on the lines of a general pact as opposed to the particular pact, a general defensive agreement as opposed to separate alliances, followed by reduction on a great ratio, the practicability of which has been proved at Washington, a solution can be reached. Given goodwill—that is the point. At the last Assembly of the League of Nations a report was presented by the Commission, of which Lord Robert Cecil was a member, and it wound up with these words: “Finally, the committee recognises that a policy of disarmament, to be successful, requires the support of the population of the world. Limitation of armaments will never be imposed by Governments on peoples, but it may be imposed by peoples on Governments.“ That is absolutely true. How are we going to apply it? Frankly, myself, I do not see that there is a great deal of value to be got by demonstrations which demand no more war. I have every sympathy with their object, but we have got to the stage when we want to get beyond words to practical resolutions. We want definite concrete proposals, and you won’t get these merely by demonstrations. They are quite good in their way, but they are not enough. What you want in this matter is an informed public opinion which sees what is practical and insists on having it.

I am speaking to you as one who for a great many years believed absolutely that preparation for war was the means of securing peace. In 1919—when I had a little time to look round, to study the causes of the war and the events of the war—I changed my opinion. I then came quite definitely to the conclusion that preparation for war, carried to the point to which it had been carried in 1914, was a direct cause of war. I had to find another path, and I found it in 1919. Lord Robert may possibly remember that in the early days of the Peace Conference I came to him and made my confession of faith, and I promised to give him what little help I could. I have tried to keep my promise, and I believe this vital problem, upon which not only the economic reconstruction of Europe and the future peace of the world, but also social development at home depend, can be solved provided you will recognise that the problem is very complex; that there is fear to be overcome; that you are content with what is practical from day to day, and accept each practical step provided it leads forward to the desired goal. I therefore most earnestly trust that the Liberal party will take this question up, and translate it into practical politics. For that is what is required.

REPARATIONS AND INTER-ALLIED DEBT

By John Maynard Keynes

M.A., C.B.; Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge; Editor of Economic Journal since 1912; principal representative of the Treasury at the Paris Peace Conference, and Deputy for the Chancellor of the Exchequer on the Supreme Economic Council, Jan.-June, 1919.

Mr. Keynes said:—I do not complain of Lord Balfour’s Note, provided we assume, as I think we can, that it is our first move, and not our last. Many people seem to regard it as being really addressed to the United States. I do not agree. Essentially it is addressed to France. It is a reply, and a very necessary reply, to the kites which M. Poincaré has been flying in The Times and elsewhere, suggesting that this country should sacrifice all its claims of every description in return for—practically nothing at all, certainly not a permanent solution of the general problem. The Note brings us back to the facts and to the proper starting-point for negotiations.

In this question of Reparations the position changes so fast that it may be worth while for me to remind you just how the question stands at this moment. There are in existence two inconsistent settlements, both of which still hold good in law. The first is the assessment of the Reparation Commission, namely, 132 milliard gold marks. This is a capital sum. The second is the London Settlement, which is not a capital sum at all, but a schedule of annual payments calculated according to a formula; but the capitalised value of these annual payments, worked out on any reasonable hypothesis, comes to much less than the Reparation Commission’s total, probably to not much more than a half.

The Breakdown of Germany

But that is not the end of the story. While both the above settlements remain in force, the temporary régime under which Germany has been paying is different from, and much less than, either of them. By a decision of last March Germany was to pay during 1922 £36,000,000 (gold) in cash, plus deliveries in kind. The value of the latter cannot be exactly calculated, but, apart from coal, they do not amount to much, with the result that the 1922 demands are probably between a third and a quarter of the London Settlement, and less than one-sixth of the Reparation Commission’s original total. It is under the weight of this reduced burden that Germany has now broken down, and the present crisis is due to her inability to continue these reduced instalments beyond the payment of July, 1922. In the long run the payments due during 1922 should be within Germany’s capacity. But the insensate policy pursued by the Allies for the last four years has so completely ruined her finances, that for the time being she can pay nothing at all; and for a shorter or longer period it is certain that there is now no alternative to a moratorium.

What, in these circumstances, does M. Poincaré propose? To judge from the semi-official forecasts, he is prepared to cancel what are known as the “C” Bonds, provided Great Britain lets France off the whole of her debt and forgoes her own claims to Reparation. What are these “C” Bonds? They are a part of the London Settlement of May, 1921, and, roughly speaking, they may be said to represent the excess of the Reparation Commission’s assessment over the capitalised value of the London Schedule of Payments, and a bit more. That is to say, they are pure water. They mainly represent that part of the Reparation Commission’s total assessment which will not be covered, even though the London Schedule of Payments is paid in full.

In offering the cancellation of these Bonds, therefore, M. Poincaré is offering exactly nothing. If Great Britain gave up her own claims to Reparations, and the “C” Bonds were cancelled to the extent of France’s indebtedness to us, France’s claims against Germany would be actually greater, even on paper, than they are now. For the demands under the London Settlement would be unabated, and France would be entitled to a larger proportion of them. The offer is, therefore, derisory. And it seems to me to be little short of criminal on the part of The Times to endeavour to trick the people of this country into such a settlement.

Personally, I do not think that at this juncture there is anything whatever to be done except to grant a moratorium. It is out of the question that any figure, low enough to do Germany’s credit any good now, could be acceptable to M. Poincaré, in however moderate a mood he may visit London next week. Apart from which, it is really impossible at the present moment for any one to say how much Germany will be able to pay in the long run. Let us content ourselves, therefore, with a moratorium for the moment, and put off till next year the discussion of a final settlement, when, with proper preparations beforehand, there ought to be a grand Conference on the whole connected problem of inter-Governmental debt, with representatives of the United States present, and possibly at Washington.

The Illusion of a Loan

The difficulties in the way of any immediate settlement now are so obvious that one might wonder why any one should be in favour of the attempt. The explanation lies in that popular illusion, with which it now pleases the world to deceive itself—the International Loan. It is thought that if Germany’s liability can now be settled once and for all, the “bankers” will then lend her a huge sum of money by which she can anticipate her liabilities and satisfy the requirements of France.

In my opinion the International Loan on a great scale is just as big an illusion as Reparations on a great scale. It will not happen. It cannot happen. And it would make a most disastrous disturbance if it did happen. The idea that the rest of the world is going to lend to Germany, for her to hand over to France, about 100 per cent. of their liquid savings—for that is what it amounts to—is utterly preposterous. And the sooner we get that into our heads the better. I am not quite clear for what sort of an amount the public imagine that the loan would be, but I think the sums generally mentioned vary from £250,000,000 up to £500,000,000. The idea that any Government in the world, or all of the Governments in the world in combination, let alone bankrupt Germany, could at the present time raise this amount of new money (that is to say, for other purposes than the funding or redemption of existing obligations) from investors in the world’s Stock Exchanges is ridiculous.

The highest figure which I have heard mentioned by a reliable authority is £100,000,000. Personally, I think even this much too high. It could only be realised if subscriptions from special quarters, as, for example, German hoards abroad, and German-Americans, were to provide the greater part of it, which would only be the case if it were part of a settlement which was of great and obvious advantage to Germany. A loan to Germany, on Germany’s own credit, yielding, say, 8 to 10 per cent., would not in my opinion be an investor’s proposition in any part of the world, except on a most trifling scale. I do not mean that a larger anticipatory loan of a different character—issued, for example, in Allied countries with the guarantees of the Allied Government, the proceeds in each such country being handed over to the guaranteeing Government, so that no new money would pass—might not be possible. But a loan of this kind is not at present in question.

Yet a loan of from £50,000,000 to £100,000,000—and I repeat that even this figure is very optimistic except as the result of a settlement of a kind which engaged the active goodwill of individual Germans with foreign resources and of foreigners of German origin and sympathies—would only cover Germany’s liabilities under the London Schedule for four to six months, and the temporarily reduced payments of last March for little more than a year. And from such a loan, after meeting Belgian priorities and Army of Occupation costs, there would not be left any important sum for France.

I see no possibility, therefore, of any final settlement with M. Poincaré in the immediate future. He has now reached the point of saying that he is prepared to talk sense in return for an enormous bribe, and that is some progress. But as no one is in a position to offer him the bribe, it is not much progress, and as the force of events will compel him to talk sense sooner or later, even without a bribe, his bargaining position is not strong. In the meantime he may make trouble. If so, it can’t be helped. But it will do him no good, and may even help to bring nearer the inevitable day of disillusion. I may add that for France to agree to a short moratorium is not a great sacrifice since, on account of the Belgian priority and other items, the amount of cash to which France will be entitled in the near future, even if the payments fixed last March were to be paid in full, is quite trifling.

A Policy for the Liberal Party

So much for the immediate situation and the politics of the case. If we look forward a little, I venture to think that there is a clear, simple, and practical policy for the Liberal Party to adopt and to persist in. Both M. Poincaré and Mr. Lloyd George have their hands tied by their past utterances. Mr. Lloyd George’s part in the matter of Reparations is the most discreditable episode in his career. It is not easy for him, whose hands are not clean in the matter, to give us a clean settlement. I say this although his present intentions appear to be reasonable. All the more reason why others should pronounce and persist in a clear and decided policy. I was disappointed, if I may say so, in what Lord Grey had to say about this at Newcastle last week. He said many wise things, but not a word of constructive policy which could get any one an inch further forward. He seemed to think that all that was necessary was to talk to the French sympathetically and to put our trust in international bankers. He puts a faith in an international loan as the means of solution which I am sure is not justified. We must be much more concrete than that, and we must be prepared to say unpleasant things as well as pleasant ones.

The right solution, the solution that we are bound to come to in the end, is not complicated. We must abandon the claim for pensions and bring to an end the occupation of the Rhinelands. The Reparation Commission must be asked to divide their assessment into two parts—the part that represents pensions and separation allowances and the rest. And with the abandonment of the former the proportion due to France would be correspondingly raised. If France would agree to this—which is in her interest, anyhow—and would terminate the occupation it would be right for us to forgive her (and our other Allies) all they owe us, and to accord a priority on all receipts in favour of the devastated areas. If we could secure a real settlement by these sacrifices, I think we should make them completely regardless of what the United States may say or do.

In declaring for this policy in the House of Commons yesterday, Mr. Asquith has given the Liberal Party a clear lead. I hope that they will make it a principal plank in their platform. This is a just and honourable settlement, satisfactory to sentiment and to expediency. Those who adopt it unequivocally will find that they have with them the tide and a favouring wind. But no one must suppose that, even with such a settlement, any important part of Germany’s payments can be anticipated by a loan. Any small loan that can be raised will be required for Germany herself, to put her on her legs again, and enable her to make the necessary annual payments.

THE OUTLOOK FOR NATIONAL FINANCE

By Sir Josiah Stamp, K.B.E., D.Sc

Assistant Secretary Board of Inland Revenue, 1916-19. Member of Royal Commission on Income Tax, 1919.

Sir Josiah Stamp said:—In discussing the problem of National Finance we have to decide which problem we mean, viz., the “short period” or the “long period,” for there are distinctly two issues. I can, perhaps, illustrate it best by the analogy of the household in which the chief earner or the head of the family has been stricken down by illness. It may be that a heavy doctor’s bill or surgeon’s fee has to be met, and that this represents a serious burden and involves the strictest economy for a year or two; that all members of the household forgo some luxuries, and that there is a cessation of saving and perhaps a “cut” into some past accumulations. But once these heroic measures have been taken and the burden lifted, and the chief earner resumes his occupation, things proceed on the same scale and plan as before. It may be, however, that the illness or operation permanently impairs his earning power, and that the changes which have to be made must be more drastic and permanent. Then perhaps would come an alteration of the whole ground plan of the life of that family, the removal to a smaller house with lower standing charges and a changed standard of living. What I call the “short period” problem involves a view only of the current year and the immediate future for the purpose of ascertaining whether we can make ends meet by temporary self-denial. What I term the “long distance” problem involves an examination of the whole scale upon which our future outlay is conditioned for us.

The limit of further economies on the lines of the “Geddes’ cut” that can become effective in 1923, would seem to be some 50 or 60 millions, because every 10 per cent. in economy represents a much more drastic and difficult task than the preceding, and it cuts more deeply into your essential national services. On the other side of the account one sees the probable revenue diminish to an almost similar extent, having regard to the effect of reductions in the rate of tax and the depression in trade, with a lower scale of profits, brought about by a lower price level, entering into the income-tax average. It looks as though 1923 may just pay its way, but if so, then, like the current year, it will make no contribution towards the reduction of the debt. So much for the “short period.” Our worst difficulties are really going to be deep-seated ones.

The Two Parts of a Budget

Now a national budget may consist of two parts, one of which I will call the “responsive” and the other the “non-responsive” portion. The responsive portion is the part that may be expected to answer sooner or later—later perhaps rather than sooner—to alterations in general conditions, and particularly to price alterations. If there is a very marked difference in general price level, the salaries—both by the addition or remission of bonuses and the general alteration in scales for new entrants—may be expected to alter, at any rate, in the same direction, and that part of the expense which consists of the purchase of materials will also be responsive. The second, or non-responsive part, is the part that has a fixed expression in currency, and does not alter with changed conditions. This, for the most part, is the capital and interest for the public debt.

Now the nature and gravity of the “long distance” problem is almost entirely a question of the proportions which these two sections bear to each other. If the non-responsive portion is a small percentage of the total the problem will not be important, but if it is larger, then the question must be faced seriously. Suppose, for example, that you have now a total budget of 900 million pounds, and that, in the course of time, all values are expressed at half the present currency figure. Imagine that the national income in this instance is 3600 million pounds. Then the burden, on a first approximation, is 25 per cent. Now, if the whole budget is responsive, we may find it ultimately at 450 million pounds out of a national income of 1800 million pounds, i.e. still 25 per cent. But let the non-responsive portion be 400 million pounds, then your total budget will be 650 million pounds out of a national income of about 2000 million pounds, or 33-1/3 per cent., and every alteration in prices—or what we call “improvement” in the cost of living—becomes an extraordinarily serious matter as a burden upon new enterprise in the future.

Let me give you a homely and familiar illustration. During the war the nation has borrowed something that is equivalent to a pair of boots. When the time comes for paying back the loan it repays something which is equivalent to two pairs or, possibly, even to three pairs. If the total number of boots produced has not altered, you will see what an increasing “pull” this is upon production. There are, of course, two ways in which this increasing pull—while a great boon to the person who is being repaid—must be an increased burden to the individual. Firstly, if the number of people making boots increases substantially, it may still be only one pair of boots for the same volume of production, if the burden is spread over that larger volume. Secondly, even supposing that the number of individuals is not increased, if the arts of production have so improved that two pairs can be produced with the same effort as was formerly necessary for one, then the debt may be repaid by them without the burden being actually heavier than before.

Now, coming back to the general problem. The two ways in which the alteration in price level can be prevented from resulting in a heavier individual burden than existed at the time when the transaction was begun, are a large increase in the population with no lower average wealth, or a large increase in wealth with the same population—which involves a greatly increased dividend from our complex modern social organism with all its mechanical, financial, and other differentiated functions. Of course, some of the debt burden is responsive, so far as the annual charge is concerned, on that part of the floating debt which is reborrowed continually at rates of interest which follow current money rates, but, even so, the burden of capital repayment remains. An opportunity occurs for putting sections of the debt upon a lower annual charge basis whenever particular loans come to maturity, and there may be some considerable relief in the annual charge in the course of time by this method.

What are the prospects of the two methods that I have mentioned coming to our rescue in this “long distance” problem? It is a problem to which our present “short distance” contribution is, you will admit, a very poor one, for we have not so far really made any substantial contribution from current revenue towards the repayment of the debt.

A Century of the National Debt

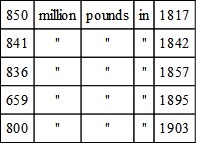

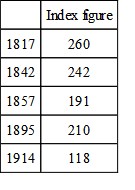

Historical surveys and parallels are notoriously risky, particularly where the conditions have no precedent. They ought, however, to be made, provided that we keep our generalisations from them under careful control. Now, after the Napoleonic wars we had a national debt somewhat comparable in magnitude in its relation to the national wealth and income with the present debt. What happened to that as a burden during the 100 years just gone by? If it was alleviated, to what was the alleviation due? I would not burden you with a mass of figures, but I would just give you one or two selected periods. You can find more details in my recent book on Wealth and Taxable Capacity. We had a total debt of—

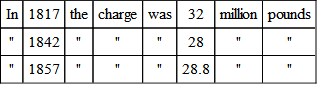

and before this last war it had been reduced to 707 million pounds. In 1920, of course, it was over 8000 million pounds. Such incidents as the Crimean and the Boer wars added materially to the debt, but apart therefrom you will see that there is no tremendous relief by way of capital repayment to the original debt. Similarly, in a hundred years, even if we have no big wars, it is quite possible we may have additions to the national debt from smaller causes. Yet the volume of the debt per head fell from £50 to £15.7, so you will see that the increasing population made an enormous difference. The real burden of the debt is of course felt mainly in its annual charge. I will take this, therefore, rather than the capital:—

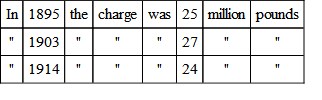

Here you will see that the reduction from 32 to 24 was 25 per cent. or a much greater reduction than the reduction of the total capital debt, and this, of course, was contributed to by the lower rates of interest which had been brought about from time to time. When we take the annual charge per head the fall is much more striking. In the hundred years it decreased from 37s. to 10s. This, however, was a money reduction, and the real burden per head can only be judged after we have considered what the purchasing power of that money was. Now, the charge per head, reduced to a common basis of purchasing power, fell as follows:—

In the year 1920 the charge per head was £7.16 and my purchasing power index figure 629. You will see that the real burden in commodities moved down much less violently than the money burden, and the relief was not actually so great as it looks, because prices were far lower in 1914 than they were early in the nineteenth century.

In view of the fact that our debt is approximately ten times that of the last century, let us ask ourselves the broad question: “Can we look forward to nothing better than the reduction of our debt by 450 millions in thirty-seven years?”