Полная версия

Полная версияContinental Monthly , Vol. 5, No. 6, June, 1864

But the greatest exhibition of the wonderful character of the Mississippi, and in which all its singular effects are most distinctly shown, is in its Delta. For a long succession of years the immense quantities of sediment, of which we have already spoken, had gradually precipitated upon this portion of the river until it reached the surface. Drift now lodged upon it: the decomposition of drift and the accumulation of other vegetable matter soon furnished a suitable bed for the growth of a marine vegetation, and now a vast area, a level expanse of waste land and marsh, is seen extending a great distance into the Gulf, ramified here and there by the outlets of the river. Indeed, so rapid have been these formations, that upon the testimony of history, the Mississippi River to-day is twenty-nine miles farther in the Gulf than it was in 1754.

Mr. Forshey, an engineer, remarks that 'the superficial area of the true Delta formation of the Mississippi, or below Baton Rouge, where the last bluffs are found, is about fifteen thousand square miles, constituting a region of mean width seventy-five miles, and mean length two hundred miles. Probable depth of alluvion is about one fifth of a mile, by inference from the depth of the Gulf of Mexico.' In the vicinity of New Orleans, boring to a depth of two hundred feet, fossils, such as shells, bones, etc., have been found. And at thirty feet specimens of pottery and other evidences of Indian habitation have been discovered. The foundation upon which rest the alluvial formations has been found to consist of a hard blue silicious clay, closely resembling that met with in the bed of the Mississippi. The most recent of the alluvial fields of the Delta have been constituted a parish, termed Plaquemine. In 1800, according to one authority, there were but very few acres in cultivation in the entire parish. Since leveeing above, the deposit has been extremely rapid, until now we find some excellent plantations in Plaquemine. Fifty miles below New Orleans the tillable land is nearly a mile in width; below there, it becomes gradually less, until it is lost in the Gulf. Still the accumulations are going on, and it is impossible even to surmise what changes the great river may yet effect in the future geography of this section of the American continent.

Considering the multitude of streams and vastness of area drained by the Mississippi, it is natural to suppose the river is much affected in the stage of its water by the seasons. We have seen that the meltings of the Rocky Mountain snows, the mountain rills of the Alleghanies, the waters of the valleys of the upper river, of the Missouri, of the Ohio, the Arkansas, the Yazoo, and the Red, all find outlet through this one stream. There are certain seasons in the year when all these widely distant localities are subject to a gradual approach of warmth from the south, until they arrive at a sort of climatic average. This creates a maximum of the supply of water. The inverse then takes place, and a minimum results. For instance, in the latter part of December, the lower latitudes of the Mississippi begin to experience their annual rains. These by degrees tend northward as the season advances. In March commence the thaws of the southern borders of the zone of snow and ice; and during April, May, and June, it reaches to the most distant tributary fountain head. The river now is at its highest. The reverse then sets in. All the tributaries have their excess, the heats of summer are at hand, drought and evaporation soon exhaust the surplus of the streams, and the river is at its lowest.

To meet the great annual excess of water in the Mississippi, nature has provided sure safeguards. These are termed bayous, and are found everywhere along the river, below the mouth of the Ohio. Additional preventives against inundation are the lagoons, or sea-water lakes, of the coast. Into these bayous and lagoons, as the river becomes high, the excess of water backs or flows. They are natural reservoirs, to ease the rise, and prevent the inevitable suddenness and danger which would result without them. In these reservoirs the water rises or falls with the river; and when the fall becomes permanent, the water in the bayous—the lagoons having outlet into the sea—falls with it, returning into the main stream, and finding entrance into the Gulf, from which it had been temporarily detained. Without the bayous the lands adjacent to the Lower Mississippi would, with very few exceptions, be subject to an annual overflow, and be perfectly worthless for certain agricultural purposes. In summer the bayous in numerous instances become perfectly dry, and give a very singular effect to the appearance of the country.

Below the mouth of the Red River the tributaries of the Mississippi cease, and the entire volume of the river is attained. As a protection against serious consequences arising out of such an immense mass of water, nature has again introduced a remedy. This consists in a number of lateral branches, which leave the river a short distance below the mouth of the Red, tending directly to the Gulf, through a continuous chain of conduits, lakes, and marshes.

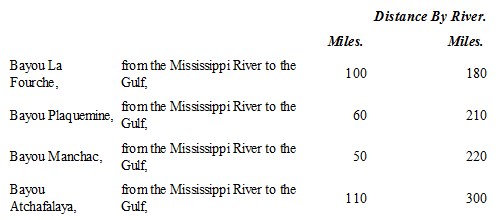

The principal bayous, which exert so important a part in regulating the stage of this part of the river, are in length and distance from the Gulf as follows:

The course of the bayous, it will be seen, have a more direct route than the river. Their average width is one thousand feet, and fall twenty-two feet. Their average velocity is about three and two tenths miles per hour. Though the rise of the river at Baton Rouge sometimes attains a height of thirty feet, so great is the relieving capacity of these lateral branches, that at New Orleans the rise never exceeds twelve feet. At Point à la Hache the difference between the highest and lowest stage is but six feet; at Fort Jackson, four feet, while it falls to low water mark when it enters the sea.

Having briefly noted the peculiarities of the Mississippi, a few facts in recapitulation may place it in a more comprehensive attitude as regards its appearance and size. In the north, after leaving the Falls of St. Anthony, the river has but the characteristics of a single stream, but below the Ohio we find it combines the peculiarities of a number. The water here begins to show signs of almost a new nature and greater density. The river develops into a much wider channel, and its peculiarities become more marked and impressive.

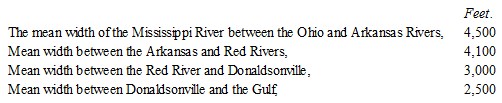

Strange as it may seem, the greatest mean width of the Lower Mississippi is at the confluence of the Ohio, and from this point it gradually becomes narrower, until it is but little more than half that width as it draws near the Gulf. This gives the river a kind of funnel shape, and if it were not for the numerous bayous and lateral branches, which we have explained, the most violent convulsion and devastation would arise. In the United States Engineer Reports we find this statement:

Above the Red River the range between high and low water is about forty-five feet, and thence to the Gulf it gradually diminishes to zero.

The greatest velocity of current is about five and a half miles per hour during floods, and about one and a half miles per hour during low water.

The river is above mean height from January to July, and below from August to December. The greatest height is attained from March to June, and the lowest from October to November.

The mud of the Mississippi is very yielding, insomuch that an allowance of several feet is often made where the draught of a vessel exceeds the clear depth of the water. We have heard of cases where steamers have ploughed successfully through four feet of it.

It is singular, too, and exhibits still more clearly what we have said of deposits, that the lower river for the most part runs along the summit of a ridge of its own formation, and annually this ridge is becoming more elevated. The inland deposits are made by the bayous and their overflow. The lands close to the river are disproportionately higher than those farther back. The average distance from the river to the swamp is about two and a half miles. And the slope in some places sinks to a depression of eighteen feet to a mile. It is upon this strip of tillable earth that the river plantations are located. By a system of drainage even much of the swamp lands now unconverted might soon be turned to profitable use.

The numerous islands and old channels of the Mississippi are also another source of wonder to the traveller. The 'cut offs,' previously explained, are mainly the cause of both. In the first instance, the river forces its way by a new route, and joins the river below; this necessarily detaches a certain amount of land from the main shore. As for the second, after the river has taken this new route, its main abrasive action follows with it. The water in the old channel becomes comparatively quiet, sediment is rapidly deposited, and in course of time the old bed loses its identity, or becomes a beautiful lake, numerous instances of which occur between the Ohio and the Red Rivers.

As the Mississippi reaches the neighborhood of the Balize the east banks slope to the sea level very rapidly, running off toward the end at a declination of three feet to a mile; after which, the land is soon lost in wet sea marsh, covered by tides. On the west side the land declines more slowly, and in some places is deeply wooded. The chenières begin where the declination ends, and the great reservoirs of the coast, the lakes and lagoons, begin.

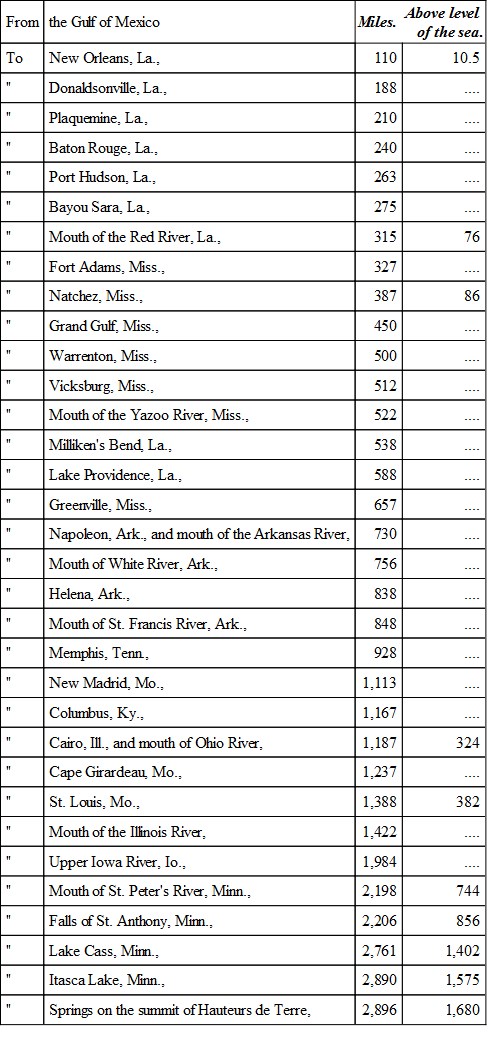

The incessant changes in the channel and filling up of the Mississippi preclude the possibility of a table of distances mathematically accurate, yet we have taken from accepted authorities the number of miles from the Gulf to the principal points along its banks. The table may be of service to the many that are daily tending to the great Father of Rivers, and those at home may be able to form, perhaps, a better estimate of the immense length of the stream, by having before them these figures:

Table of Distances and Altitudes on the Mississippi

The Lower Mississippi presents another feature that should not be forgotten, and which sets forth a great design. Immense forests of cottonwood and ash are to be seen growing along its banks. These trees are of rapid growth, and afford excellent (in fact the best, with the exception of coal) fuel for steamers. Indeed, they constitute much the greater portion of wood consumed in river navigation. So suitable is the rich alluvion of the river banks to the growth of these trees, that in ten years they attain to a sufficient size for felling. Plantations lying uncultivated for a single year, in the second present a handsome young growth of cottonwood. This fact is now very well proven on the Mississippi; the war has ruined agricultural labor almost entirely. No apprehensions are ever felt by steamboat men on the subject of fuel; the supply is inexhaustible and reproducing.

The other woods found upon the river, but not, let it be said, to the extent of the cottonwood or the ash, are the live and water oak, swamp dogwood, willow, myrtle, wild pecan, elm, and ash. The cypress tree is found in extensive forests back from the river in the swamps. This tree attains an enormous height, and is without branches until attaining the very top, and then they are short and crooked, presenting a very fine and sparse foliage. The wood of the cypress is very little used upon the river, not, perhaps, in consequence of its inferiority of quality, but the difficulty of access to it.

In conclusion, we cannot withhold a few words upon the singular typical similarity between the appearance of vegetation upon its banks and the river itself. Gray forests of cypress, the blended foliage of the oak, the cottonwood, and the ash, with a charming intermixture of that beautiful parasitic evergreen, the mistletoe, above Vicksburg, suggest the blooming grandeur of the stream. Below, the appearance of a new parasite, the Spanish moss, draping the trees with a cold, hoary-looking vegetation, casts a melancholy and matured dignity upon the scene. Like the gray locks of age, it reminds the passer by of centuries gone, when the red savage in his canoe toiled upon its turbid flood; it recalls the day of discovery, when De Soto and La Salle sought its mighty torrent in search of gain, and found death; and now looms before us the noblest picture of all, the existence of a maturing civilization upon its banks. Associated thus with an ever-present suggestion of a remarkable and ever-forming antiquity, the Mississippi becomes indeed the wonder of waters. Ponce de Leon, that most romantic of early Spanish explorers, traversed the continent in search of a 'fountain of everlasting youth;' the powerful republic of the West, has found in the 'Father of Waters' a fountain and a stream of everlasting, vigorous life, wealth, and convenience.

SKETCHES OF AMERICAN LIFE AND SCENERY

IV.—MOUNTAIN WAYS

Lucy D–. Aunt Sarah, did you ever read the Declaration of Independence?

Mrs. Grundy. What a question! In my youth it was read regularly, once a year, at every Fourth of July celebration.

Lucy D–. Did you ever, when listening to it, consider that your interest in its enunciation of principles was merely incidental, not direct?

Mrs. Grundy. How so?

Lucy D–. The 'all men' that are born 'equal,' and with an 'inalienable right to liberty,' does not include you, because, although you are white, you are a woman.

Mrs. Grundy. What covert heresy is this, Lucy, with which you are endeavoring to mystify my old-fashioned notions?

Lucy D–. I advocate no theory. I merely state a fact. My own belief is, that men are born very unequal (I do not mean legally, but really, as they stand in the sight of God), and that they, as well as we, are free only to do what is right in the fulfilment of inalienable duties. 'Life' and the 'pursuit of happiness' must both yield to the exactions of such duties. I must confess, however, that, let my abstract views be as they may, I have occasionally embraced in their widest extent the generalizations of the Declaration of Independence; and nowhere has the right of 'Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness' seemed to me so precious and delightful a possession as, when seated on top of a stage coach, I have breathed the exhilarating atmosphere of some elevated mountain region. As to equality, I must also say, that there especially do I feel my inferiority to, and dependence on the driver, who, in his sphere, reigns a king.

Mrs. Grundy. In my day, ladies were always expected to take inside seats.

Lucy D–. Yes, and be shut up behind a great leather strap, so that if anything happened, they would be the last to reach the door! I have a few notes of a stage-coach journey, made last summer. If you like, I will read it to you while you work on that interminable afghan. By the way, Aunt Sarah, I do not think you have labored quite so energetically since the late decision made by the Metropolitan Fair in regard to raffling. How is that?

Mrs. Grundy. My dear, I must acknowledge that my ardor is a little lessened since I began this piece of work, for then I had not only a vision of the poor soldiers to be aided by my labor, but I also fancied that this warm wrapping, instead of adding a new lustre to the carriage of some luxurious lady, might perchance fall to the share of some poor widow; and these beautiful embroidered leaves and blossoms might delight some sickly child, whose best covering had hitherto been a faded blanket shawl, and whose mother was too poor to afford the indulgence of real flowers, purchased from some collection of exotics, or plucked by the pale fingers from some fragrant country wayside. However, I know that was an idle fancy, and the imagination is a dangerous guide. I surely would never call in question the soundness of a decision made by so many excellent and respectable people. Read on, if you please. You know me to be a patient listener.

Lucy D–. Yes, dear aunt, and I know, too, that charity—that crown of virtues—can warm and expand the primmest conventionality, and lend bright wings of beauty to the most commonplace conception. The same Divine Love that fringes dusty highways with delicate, fragrant blossoms, can cause even the arid soil of worldliness to teem with lovely growths and refreshing fruits. But, a truce to this digression, to which, as I foresaw, you give no heed; and now to my notes:

One cool, sunshiny morning in August, a lady traveller, bent for once on gratifying the whim of seeing what lay beyond the blue hills in the far distance, left the Laurel House (Catskill Mountains), and took her way toward Tannersville. Two ladies, charming companions, accompanied her as far as the bridge over the mill stream, where she struck into a neglected byway, leading past a melancholy graveyard. The air was delicious, the mountains were clear, but softened by a dreamy haze; each cottage garden was bright with phlox, bergamot, mallows, and nasturtiums, and the soul of the traveller was filled with gratitude that this earth had been made so beautiful, and she had been given health, strength, opportunity, and a stout heart to enjoy it.

Tannersville reached, an outside seat was secured on the Lexington stage. The sharers of my lofty station were a gentleman on his way to join wife and children at Hunter, and a tattered, greasy-looking Copperhead.

The 'sunny hill' (Clum's) was soon left behind; the opening of the Plattekill Clove, with its beautiful mountains and deep hollows (Mink and Wildcat), passed, and the distant peaks beyond Lexington loomed up fair as the enchanted borders of the land of Beulah. The hay was nearly gathered in, and the oats were golden on the hillsides. Men for farmwork were evidently scarce, and the driver said they had nearly all gone to the war. The Copperhead remarked: 'I was always too smart for that, I was.'

The driver told him his turn would come yet, for he would certainly be drafted. Copperhead said he had the use of only one arm. Driver opined that would make no difference; they took all, just as they came. Copperhead grumbled out: 'Yes; I know we ha'n't got no laws nohow!'

At Hunter, the wife and two ruddy little boys came out to meet the expected head of the family. A bright and happy meeting! The Copperhead also got down, and took seat inside the stage, where he was soon joined by a country lassie, whose merry voice speedily gave token of acquaintance and satisfaction with her fellow traveller.

Opposite Hunter is the most beautiful view of the Stony Clove. The high and narrow cleft opens to the south, and I thought of loved ones miles and miles away.

Beyond Hunter, a long, straggling village, with some neat houses, the road becomes smoother, and gradually descends along the east bank of the Schoharie, which it rarely leaves. The meadow lands widen a little, and the way is fringed by maples, beeches, alders, hemlocks, birches, and occasional chestnuts. The stream is rapid, clear, and, though without any noteworthy falls, a cheerful, agreeable companion. The mountains on the left bank are steep and rugged; near Hunter, burnt over; afterward, green to the top, and, while occasionally curving back from the stream, and thus forming hollows or ravines, still presenting not a single cleft between Stony Clove and the clove containing the West Kill, and opening out from Lexington toward Shandaken. The West Kill enters the Schoharie a little below Lexington, and the East Kill flows in above, near Jewett.

Every farm glittered with golden sunflowers. I saw one misguided blossom obstinately turning its face away from the great source of light and heat. Every petal was drooping, and I wondered if the dwellers in the neighboring cot heeded the lesson. The buckwheat fields were snowy with blossoms and fragrant as the new honey the bees were industriously gathering.

Lexington is a lovely village, with pretty dwellings, soft meadows, and an infinite entanglement of mountains, great and small, green and blue, for background in every direction. I had already been warned that the stage went no farther; and, as my destination that evening was Prattsville, some means of conveyance was of course necessary. The driver feared the horses would all be engaged haying, and asked what I would do in case no wagon could be found. I replied that, as the distance from Lexington to Prattsville was only seven miles, and I had no luggage, it might readily be accomplished on foot. He opened his eyes, and, perhaps, finding the Lexington hotel not likely to be benefited by my delay, cast about for some way of obliging me. As we drove up to the post office, the door was found locked, and Uncle Samuel's agent absent, which circumstance, taken in connection with the fact that the mail comes to Lexington only twice per week, struck me as decidedly 'cool.'

By six o'clock I found myself seated in a comfortable buggy, behind a sleek, fleet pony, and beside an old gentleman, whose upright mien and pleasant talk added no little to the enjoyment of the hour. The evening lights were charming, the hills wound in and out, the Schoharie rippled merrily over the cobble stones or slate rocks forming its bed, and the clematis and elder bushes gently waved their treasures of white blossoms, silky seeds, or deepening berries, in the soft summer air. By and by the slate cliffs rose precipitously from the river shore, leaving only room sufficient for the road, which, is in fact, sometimes impassable, when the rains or melting snows have swollen the singing river to an angry, foaming, roaring flood. My companion told me of the agriculture of the district, of the wild Bushnell Clove, of bees and honey making, and of the Prattsville tanneries, which he stigmatized as a curse to the country, cutting down all the trees, and leaving only briers and brambles in their stead. He also told me of two brave sons in the Union army, and of a married daughter far away. The oldest boy had been wounded at Gettysburg, and all three children had recently been home on a short visit. 'Children,' said the old man, 'are a heap more trouble when they are grown than when they are little; for then they all go away, and keep one anxious the whole time.'

We drove under the steep ledges, the hills of Beulah were passed, and Prattsville reached.

The following morning was bright and clear, but warm. I rose early, and went up on the high bluffs overlooking the town. Below was a pretty pastoral view of stream, meadow, hop fields, pasture lands with cattle, sundry churches, and neat white houses, shut in by great hills, many bare, and a few still wooded. Passing beneath the highest ledge, I came upon an old man, a second Old Mortality, chipping away at the background for a medallion of the eldest son of Colonel Zadoc Pratt, a gallant soldier, who fell, I believe, at the second battle of Manassas. On a dark slab, about five hundred and fifty feet above the river, is a profile in white stone of the great tanner himself. An honest countryman had previously pointed it out to me, saying: 'A good man, Colonel Pratt—but that looks sort of foolish; people will have their failings, and vanity is not one of the worst!' On the above-mentioned ledges are many curious carvings, a record of 'one million sides of leather tanned with hemlock bark at the Pratt tanneries in twenty years,' and other devices, such as niches to sit in, a great sofa wrought from the solid rock, and a pretty spring.

At ten o'clock the stage came from Delhi, which place it had left at two in the morning. Seventy miles from Delhi to Catskill—a good day's journey! It was full, and our landlord put on an extra, giving me a seat beside the driver, and filling the inside with men. Said driver was a carpenter, and an excellent specimen of an American mechanic—intelligent and self-respecting. This is a great cattle and dairy region, and we passed several hundred lambs on their way to the New York market. The driver pitied the poor creatures; and, when passing through a drove, endeavored to frighten them as little as possible. 'Innocent things!' said he, 'they have just been taken from their mothers, and know not which way to turn. I hate to think of their being slaughtered, for what is so meek and so joyous as a young lamb!'