Полная версия

Полная версияContinental Monthly , Vol. 5, No. 6, June, 1864

The Positive Element or Factor of Oral Speech, the Absolute Reality or 'Affirmation' of Language, is Vocal Utterance, or, specifically, the kind of Sound called Vowel.

The Negative Element or Factor of Oral Speech, the 'Negation' of Kant, as illustrated in the Speech Domain, is Silence; the Silences or Intervals of Rest which intervene between Sounds (and, by repetition, between Syllables, Words, Sentences, and the still larger divisions of Speech).

The Limitational Element of Oral Speech is Consonantism, or, specifically, the Consonant Sounds, which for that reason are otherwise denominated Articulations, or jointings; as they are the breaks of the otherwise continuous vocal utterance of Vowel Sound, and, at the same time, the joinings between the fragments of Vowel Sound, namely, the Vowels, and the surrounding and intervening medium of Silence. The Consonants thus become, in a sense, the Bony Structure, or Skeleton of Speech, the most prominent part, that which furnishes the fossil remains of Language, which are investigated by the Comparative Philologists.

Sound, the Positive Element or Factor, the Affirmation, the Eternal Yea, the Absolute Reality, is the Something of Speech.

Silence, the Negative Element or Factor, the Negation, the Eternal Nay, the Absolute Unreality, is the Nothing of Speech.

Articulate Sound, the Resultant Element, the Limitation or Articulation, the Eternal Transition, the Arriving and Departing, is the Existential Reality, which comes up between and out of the Absolute Vocality (quasi-negative), and the Absolute Silence.

But the Vowel Absolute, the continuous, unbroken, unarticulated, undifferentiated, monotonous Vowel-Sound, would be precisely equivalent to Silence. This, then, illustrates the famous fundamental aphorism of the Philosophy of Hegel: Something = (equal to) Nothing; and the seemingly absurd Hegelian affirmation that the real Something is the resultant of the conjunction of two Nothings.

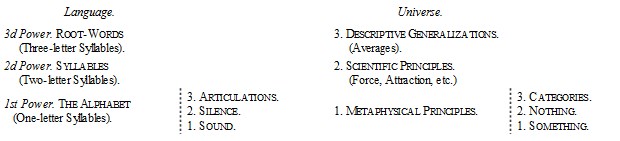

What Kant denominates Quality, would be, for some uses, better denominated Elementism or Elementality, and the Domain in which this principle dominates might then be called the Elementismus of such larger Domain as may be under consideration. Thus the Elementismus (or Elementary Domain) of Language would include Sounds, or the Alphabet, Syllables, and Root-Words. These are three powers or gradations of the Roots of Language. This same domain might therefore be called the Radicismus or Root-Domain of Language. Typically, one-letter, two-letter, and three-letter roots, again, represent these three powers.

The Elementismus or Radicismus of the Universe, correspondential with that of Language, consists of the Metaphysical, the Scientific, and the Descriptive Principles of Being. The parallelism is exhibited throughout in the following table:

It results from this table that the deep Metaphysical Domain, wherein Aristotle and Kant were laboring to categorize the Universe, is the Alphabetic Domain of Universal Being; and that their profound effort was, so to speak, to discover The Alphabet of the Universe. It also appears that the Syllabarium of the Universe, and typically the open two-letter syllables of Language, as bi, be, ba, correspond as analogues with the Physical Principles which lie at the basis of the Sciences; and finally, that the completed Root-Words, typically the closed three-letter syllables, or usual monosyllabic root-words, as min, men, man, correspond with the descriptive generalizations or general averages of Natural Science, as Universe itself, Matter, Mind, Movement, etc.

These analogies need further elaboration and confirmation to render them perfectly clear and to establish them beyond cavil—such as space here does not admit of. Let us hurry on, therefore, to the Relational or Constructive Domains of Language and the Universe, where the analogies are more obvious.

The second of Kant's groups of Categories, in the order in which it is most appropriate now to consider them, he denominates Relation. Relation is that which intervenes between the Parts of a Whole.

Prepositions are especially defined in Grammar as words denoting relations. Our attention is thus turned in the Domain of Language to the Parts of Speech; and to the Syntax (putting together), or Construction of these Parts into the wholeness of Discourse. This is more specifically the Department of Grammar. Conjointly these are what may be denominated the Relationismus of Language. This is the Domain immediately above the Elementismus. In the same way the division of the human body or any other object into Parts, Limbs, Members, etc., and the recombination of these into a structural whole, arises in the scale of creation above the Domain of Elements (Ultimate, Proximate, Chemical, etc.), this last embracing only the qualitative nature of the substances entering into the structure. In the Universe at large, therefore, this Relational Domain is that in which we shall find Things, Properties, Actions, and, specifically, the Relations between such, and their Combinations into Structures and Departments, Branches, or Limbs of Being, and finally into the total Universe itself, which is the analogue of the totality of Language.

Relation has a threefold aspect: first, in respect to Space; second, in respect to Time; and third, in respect to Instance or Present Being, the conjunction of the Here and the Now.

The first of these aspects subdivides into what Kant denominates, 1. Substance, and 2. Inherence.

The second of these aspects subdivides into what Kant denominates, 1. Cause, and 2. Dependence.

The third of these aspects of Relation Kant sums up in the term Reciprocal Action.

Commencing with the first of these three subdivisions of Relation, and making our application within the Domain of Language, it is obvious that it refers to the Substantive and Adjective region of Grammar; Substance relating to Substantives, and Inherence (or Attributes) to Adjectives; or otherwise stated, thus:

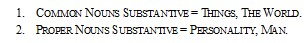

The one Thing inclusive of all minor Things is the Universe. The Universe as Thing, or the concrete domain of Being, subdivides into the world of Things proper as distinguished from the Personal world, or the Human world or Man. This first division of the substantive Universe corresponds with the first grand grammatical division of Nouns Substantive into 1. Common Nouns Substantive, and 2. Proper Nouns Substantive.

Common Nouns Substantive correspond with Things proper, not aspiring to the rank of Personality; Things put in contrast with Persons; Things in that sense in which we speak of a person derogatorily as a mere thing; hence, common or ordinary, and as a common, undistinguished herd of objects, only named and discriminated by the class-name of the class of objects to which they belong.

Proper Nouns Substantive are the individual and distinctive names of Men, Women, and Children. Hence they belong to and correspond with the domain of Personality, or to that of Man as against the world of mere Things. Some objects, lower in the scale of Being than man, are treated with that respect and consideration which ordinarily attach to Human Beings, and are then dignified by applying to them Proper Names. These are especially the Domestic Animals immediately associated with man; Mountains, Rivers, Lakes, etc. Restated, this discrimination is as follows:

It is to be borne in mind that, as a minor proportion of mere Things are raised to the dignity of wearing Proper Names, so, on the other hand, Men, though appropriately distinguished by prenomens and cognomens, may also sink to the character of Things, and be mentioned by class-names. Thus it is that throughout Nature one domain overlaps another domain, and all of our discriminations, though made in terms as if absolute, signify, in fact, merely the preponderance; thus, when we say, that Proper Names apply to the Human Domain, that is true in preponderance, but not absolutely or exclusively; and when we say that Common Names apply to Things below Persons, the statement is true in preponderance, but not absolutely or exclusively.

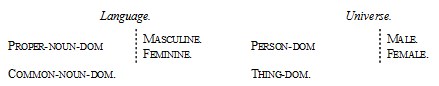

Proper Names—The Human World in Language—are, in the next place, distinguished by Gender, as that word itself is distinguished by Sex. By the principle of Overlapping, above explained, this distinction of Gender or Sex descends in a minor degree into the Thing World; in a large degree to the Animal World below man: in less degree to the Vegetable World; and in the least degree to the Mineral and Abstract World. But characteristically and predominatingly, Sex is predicated of Humanity, where it is developed in its highest perfection; and in the same degree Gender in Grammar is, in predominance, confined to the Proper Nouns Substantive. Masculine and Feminine are the only Proper Genders. Neuter Gender means of neither Gender, and includes the great mass of Common Nouns, or the Thing World, as distinguished from Personality.

Reversing the order, and resuming the above discriminations in the two domains, Language and the Universe, they are as follows:

Again, in this Concrete World, the world of Persons and Things, Number reappears, and guides the next great Grammatical division of Nouns Substantive; and the ruling numbers are, again, One, Two, Three.

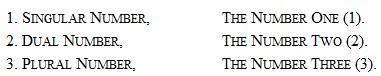

The Number One corresponds with the Singular Number in Grammar, and with the Individual or Single Person (or Thing) in the Universe at large. The Number Two corresponds with the Dual Number in Grammar, and with the Couple or Pair in the World of Persons (and Things); and finally the Number Three corresponds with the Plural Number in Grammar and with Society or the many among Persons (and Things); or in tabular form, thus:

The Number Three, as the first Plural Number above the Dual, is the Head and Type of Plurality in the grammatical discrimination, and stands representatively for all Plurality.

One, Two, and Three, are the Representative Numbers and Heads of the whole Cardinal Series of Number.

First, Second, and Third are the corresponding Representatives and Heads of the Corresponding Ordinal Series of Number. These latter numerals find their representation, grammatically, in the next Grand Grammatical Distribution of the Proper Nouns Substantive, namely, Person, so called, or, specifically, the

1st Person,

2d Person, and

3d Person (of Proper Nouns).

This distribution represents properly the Rank or Degree of Persons in the Hierarchy of Personality; the Ego ranking naturally as 'Number One.' Deference or Grace teaches us afterward to defer to the personality of others, and converts our primitive notions of rank into opposites, in a way which is indicated by the honorific use of Thou in addressing the Supreme, etc.

This idea of Personal Rank, the Hierarchical Ascension of Individuality or Personality in Society, abstracted from the particular Individuals, and rendered purely official, becomes nominally a new Part of Speech, and is the whole, substantially, of what we denominate the Pronouns.

The Pronoun, as a Part of Speech, is, therefore, the Analogue, within the Lingual Domain, of The State or the Constitution, governmentally, of Human Society, the ascending and descending rank of individuals in the social organization, the Heraldic Schedule of Man.

Finally we arrive at the consideration of the Casus or Case of Nouns Substantive.

The Accidents of Life or Being, the occasional states of Men or Things, as acting or being acted upon, or simply as related to each other in Space, or otherwise, are here represented. It is this which is meant by Case, from the Latin casus, itself from the Latin cadere, TO FALL, or to FALL OUT or HAPPEN. In the old Grammars, the Cases of the Nouns are denominated Accidents. Ac-cid-ent, is from ad, to, and cadere (cid), TO FALL; and the same root with ob (oc), gives us oc-cas-ion, oc-cas-ionally, etc.

The Accidents of Being are a special kind of Inherence to the Substance of Being; the Relational kind par excellence, as distinguished from the Qualitative kind; which last is denoted by the proper Adjectives. The Oblique Case of a Noun Substantive, whether formed by an Inflexion or by a Preposition, is therefore nothing else than a special kind of Adjective, destitute of the property of Comparison, because it denotes the Accident instead of the Quality of Being, and because Accidents or Relations between Things do not vary by degrees of Intensity as Qualities do.

The above description of the Cases of Nouns applies especially to the Oblique Cases; that is to say, to all except the Nominative Case.

The Nominative Case is itself susceptible of being regarded as an Accident; but its more important office is that of the Subject of the Proposition, which takes it out of the minor category of an accident, or at least subordinates this latter view of its character.

The Accidents of Being in the Universe at large are therefore the analogues of the oblique cases of Nouns Substantive in the Domain of Language; the Nominative Case representing, on the contrary, the central figure in the particular member of discourse, and that which the accidents or falls (casus) are perceived to relate to or affect.

Substantives and Adjectives were both formerly included under the term Nouns or Names; and we have still to distinguish, when they are under special consideration, as they are here, Nouns Substantive, and Nouns Adjective.

By regarding all the Oblique Cases of Nouns Substantive as a species or variety of Nouns Adjective, and so classifying them along with the Adjectives proper, the Nominative Case alone remains to represent the Substantive, in the higher and exclusive sense of the term. This is then, at the same time, The Subject. The terms employed to designate them sufficiently indicate this identity: Substantive, from sub, UNDER, and stans, STANDING; and Subject, from sub, UNDER, and jectus, THROWN or CAST. These are, therefore, nearly etymological equivalents.

Before passing to the consideration of the Subject and the Proposition, let us finish with the Nouns Adjective, to which we have only given an incidental attention.

These are the representatives of Incidence or Attribution; and correspond to the entire adjectivity pertaining to the substantiality of the real or concrete Universe; both Substance and Incidence falling as parts of one domain within the larger domain of Relation, which in Language is the domain of Grammar proper, including Etymology and Syntax.

It may now be shown that this Adjective World is so much a world by itself that Kant's namings for the four groups of the Categories of the Understanding, which we are here enlarging to be the Categories of All Being, are precisely the most appropriate namings for the subdivisions of the Adjective World. These are:

1. Adjectives of Quality.

2. Adjectives of Relation.

3. Adjectives of Quantity.

4. Adjectives of Mode.

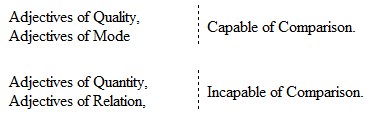

1. Adjectives of Quality are those which designate the qualities of things as good or bad, etc. They are susceptible of three Degrees of Comparison; and are, without due consideration, usually regarded by Grammarians as if they constituted the whole of the Adjective World.

2. Adjectives of Relation are, as we have seen, (chiefly) the Oblique Cases of the Noun Substantive. They admit of no Degrees of Comparison. These have not heretofore been regarded as Adjectives; but broadly and philosophically considered, they are so.

3. Adjectives of Quantity are the Numerals, which always instinctively find their way among the Adjectives in the Grammar Books, without their presence there being duly accounted for, that part of speech having been usually defined as relating exclusively to the Quality of Things. These numeral Adjectives subdivide into Ordinal Numerals and Cardinal Numerals; and, like Adjectives of Relation, they are not susceptible of being varied by the Degrees of Comparison.

4. Adjectives of Mode relate to the Conditions of Existence, as necessary and unnecessary, important and unimportant, etc. They are somewhat ambiguous as to their susceptibility to comparison. It is over this class of Adjectives that the Grammarians dispute. If a thing is necessary, then, it is said, it cannot be more necessary, or most necessary, the Positive Case being itself Absolute or Superlative. In some cases this rule is not so clear, and there is doubt whether it is proper to apply the signs of Comparison or not. We may correctly say more important and most important; and on the whole the Adjectives of Mode, or Modal Adjectives, are to be classed as capable of Comparison.

These four classes of Adjectives again classify in respect to their usual susceptibility to comparison, as follows:

The Principle of Comparison is itself hierarchical, or pertaining to gradation or rank divinely ordained; or as the mere scientist might prefer to say, naturally existent. It repeats, therefore, in an echo, or correspondentially, The Person (First, Second, Third) of Nouns Substantive and Pronouns; and has relation to the Three Heads of the Ordinal Series of Number, 1st, 2d, 3d; as The Number of Nouns Substantive (Singular, Dual, and Plural) has relation to the Three Heads of the Cardinal Series of Number, 1, 2, 3.

The Qualities, the Relations, the Numerical Character, and the Modal Condition of Things, are conjointly an Adjunct World to the Real World of Persons and Things, in the Universe at Large; and taken collectively, it is that domain or aspect of the total Universe which is the scientific echo to or analogue of the Part of Speech called Adjective in the Grammar of Language. The Substantivity and the Adjectivity, taken again collectively with each other, are the totality of the Concrete Universe considered in a state of Rest. The Movement of the Universe is expressed by the verbal department of Language, and will receive our subsequent attention. It is, therefore, from within this department that our concrete analogues of the larger Abstractions of the Universe, Nature, Science, and Art, namely, The World, Man, and the Product of Man's labor, were taken. They belong to the Substantivity (Kant's Substance) of the Universe, and their qualities, relations, number, and mode of being belong to the Adjectivity of the Universe (Kant's Inherence); and these two departments of Universal Being or of the possible aspects of Universal Being are the Scientific Analogues, in the Universe at large, of Nouns Substantive and Nouns Adjective, in the Grammar Department of the total distribution of the little Universe of Language; which is the point to be here specially illustrated and insisted upon.

We pass now to the consideration of the Verb and Participle, related to Movement. The Great Noun Class of Words, including the Nominative Noun Substantive, not yet brought into action and made to functionate as Subject or Agent, together with the whole Adjective Family of Words as above defined, is without Action. These words, and correspondentially, the Things and their Attributes which they represent in the Universe at large, are static or immovable. The Universe, viewed in the light of them solely, is a Universe at rest, or, as it were, arrested in its progression through Time, and existing only in Space; for Time has relation to Motion, as Space has relation to Position or Rest. This aspect of the Universe or of Language may therefore be appropriately denominated Statoid (or Spaceoid). The relations between the Parts of this Aspect, denoted by the Prepositions and Conjunctions, are inert or static relations, concerning predominantly Position in Space, as above, below, etc.

When the Substantive proper (the Nominative Case) passes over and becomes functionally a Subject (we will consider, first, the case where the Verb is Active Transitive, and the Subject therefore an Agent), we pass from Statism to Motism; or from Rest to Movement. This is, at the same time, to pass from the Domain or Kingdom of Space to the Kingdom or Domain of Time (or Tense).

Noun-dom (in its largest extension, including Nouns Substantive and Nouns Adjective, together with their Words of Relation, Prepositions and Conjunctions) constitutes, therefore, the Statismus (or Domain of the Principle of Rest) within the Relationismus (or Domain of Parts and their Construction, or Syntaxis into a whole) of the larger Domain of Language, which might then be properly denominated the Linguismus of the Universe. (Every new Science has to have its new nomenclature. Let the reader not be repelled, therefore, by these innovations upon the speech usages of our Language; their great convenience, and their actual necessity even for the right discussion of the subject, furnishing their sufficient apology.)

To determine what the limits of the corresponding Domain are in the Universe at large, and its proper technical designation, it is only necessary to go back upon the analogues already indicated. We have, then, the Statismus of the Relationismus of the Universe; which is the Structural Universe, viewed in respect to the relationship between the parts and the whole, and as if arrested in Space, or, what is the same thing, abstracted from Movement in Time.

In going over to the new Domain in Language,—the Grammar of the Verb and Participle,—we pass then, technically speaking, to the Motismus of the Relationismus of Language; and in going over to the corresponding Domain of the Universe at large, we pass to the Motismus of the Relationismus of the Universe, in which action and the relations between actions are concerned.

Since Motion and Action involve the idea of Force or Power, for which the Greek word is dynamis, furnishing the English words Dynamic and Dynamics, our Philosophers have chosen the distinction Static and Dynamic, instead of Static and Motic, the true distinction, and have in that way obscured and disguised from themselves even the fundamental and all-important relationship of these two great Aspects of Being, with the two great negative Grounds or Containers of all Being; namely, with Space and with Time respectively.

It is here, in the Domain of Movement and Time, the Motismus of Language, and especially of Grammar,—the Relationismus of Language,—that the Grand Lingual Illustration or Type of the Second Subdivision of Kant's Group of Relation occurs;—the subdivision which he should have denominated Tempic, as distinguished from the former Subdivision (of Substance and Inherence), which should then have been called Spacic.

This Tempic Sub-Group of Relation again subdivides, as already stated, into 1. Cause, and 2. Dependence.

The Subject of a Proposition, in the Active Voice, which is the Typical or Direct Expression of Action, is the Agent or Actor in the performance of the given Action. To be an agent is to act; and to act is to exhibit an effect, the Cause of which resides in the Agent. Agent and Cause are thus identified. In other words, the Nominative Case, in the Active Transitive Locution, is the type and illustration of the Sub-Category, Cause, in the Group of Relation, as conceived by the great German metaphysician. His Correlative Sub-Category, Dependence, is the Action itself, resulting from the Activity of the Agent, and expressed by the Verb and its dependencies.