Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 67, No. 411, January 1850

Berwickshire—

Robt. Hunter, Swinton Quarter, Coldstream.

Wm. Dove, Wark, Coldstream, attests Mr Dudgeon's only.

Robt. Nisbet, Lambden, Greenlaw.

Roxburghshire—

R. B. Boyd, of Cherrytrees, Yetholm.

Nicol Milne, Faldonside.

Wm. Broad, Clifton Hill, Kelso.

Fred. L. Roy, of Nenthorn, Kelso.

James Roberton, Ladyrig, Kelso.

Fifeshire—

James B. Fernie, of Kilmux.

John Thomson, Craigie, Leuchars.

Forfarshire—

Alexander Geekie, Baldowrie, Coupar-Angus.

David Hood, Hatton, Glammis.

James Adamson, Middle Drums, Brechin.

Wm. Ruxton, Farnell, Brechin.

Aberdeenshire—

Robert Walker, Portleithen Mains, Aberdeen.

John Hutchison, Monyruy, Peterhead.

Robt. Simpson, Cobairdy, Huntly.

William Hay, Tillydesk, Ellon.

William M'Combie, Tillyfour, Aberdeen.

Elginshire—

Peter Brown, Linkwood, Elgin.

Kincardineshire—

J. Garland, Cairnton.

R. Barclay Allardyce, of Ury, Stonehaven.

James Falconer, Balnakettle, Fettercairn.

We further subjoin extracts from the letters of several of these gentlemen, containing remarks or suggestions about the statements: —

"I was favoured with your letter and enclosure of the 8th inst. I have gone carefully over the statements of the working of a farm, and the quantity and value, at present prices, of the produce – all of which appear to me to be fairly stated. I have drawn up a statement of the returns of produce of a 400 acre farm in Mid-Lothian, which, if it meets your approval, you are at liberty to publish along with the others. The prices of the grain which I have assumed are in some instances higher than those of Messrs Dudgeon and Watson; but I think this can be explained, by the farm being situated in the neighbourhood of the best market." – (THOMAS SADLER, Norton Mains, Ratho.)

"I am in receipt of your letter of the 8th current, inclosing statements by various eminent agriculturists, showing the difference between times past and to come for farmers. I perfectly coincide with these gentlemen; and consider their valuation of produce and price to be average and just: although we are not at present realising the prices quoted, yet it is fair that an allowance should be made this year for the full crop wheat." – (ANDREW HOWDEN, Lawhead, Prestonkirk.)

"On looking over the statements you handed me of the comparative value of farm produce, under protection and free-trade prices, as drawn up by Messrs Watson and Dudgeon, my first impression was, that they had fixed the protection price of grain too high; but on taking the average prices of my own sales of the different kinds of grain, as entered in my corn-book, from crop 1827 to that of 1845, I find they are not beyond what I have actually received during that period. The only points in which I differ from these gentlemen's statements are in the rents fixed by them for land yielding the crops they mention, which in my opinion should not be less than 35s. per acre, and £1000 might be taken from the sum put down as necessary for floating capital by Mr Watson; and I think, upon an average of years, that £50 should cover the loss of live stock. These alterations I have suggested would make no material change in the calculations, which, in the main particulars, I hold to be perfectly correct." – (ROBERT NISBET, Lambden, Greenlaw.)

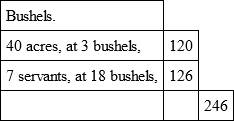

"I have to acknowledge the receipt of your agricultural statements, and have carefully examined them, especially Mr Dudgeon's, as being the one with which I am best acquainted. I have tested its various items, and have found them generally correct, and in agreement with my own practical experience. There is one, however, which I consider too low – viz., the allowance of barley for seed and servants. Mr Dudgeon, I believe, uses a drill-sowing machine, and, by that means, will save about one bushel of seed per acre; but as this mode of sowing has not come into general use, the following is what is commonly found necessary —

From the general accuracy of the statement, I have no hesitation in consenting to the use of my name in connexion with it." – (WILLIAM BROAD, Clifton Hill, Kelso.)

"Having for several years farmed land in the vicinity of Kelso, and of a description somewhat similar to that described by Mr Dudgeon, Spylaw, I beg to say that I agree essentially with the statement subscribed by him. It exhibits, in my opinion, a fair estimate of the returns of such a farm when in good condition, and of the necessary expenses attending the working and keeping it in good order. In many cases, a much larger sum has been expended in improvements, but that would probably make no great difference in the result; for while the occupier would have a larger sunk capital to draw out of the land, he would probably have a smaller rent to pay. I may remark, that even where land has been thoroughly drained, or does not require it, there is usually a large sum sunk at the commencement of a lease in liming, for I consider that almost all land in this district would require to be limed during the currency of a lease, in order to yield full crops." – (FRED. L. ROY, Nenthorn, Kelso.)

"I think Mr Dudgeon makes too little allowance for stock and insurance, (£50.) Mr Watson's allows double, (£100,) which is low enough. Some of my neighbours here have lost from £200 to £300 by pleuro-pneumonia upon cattle alone, independent of other stock. I also think they are both wrong in the average quantity of grain grown. It may be done upon a farm of good land, in high condition, but – I mean taking a whole county – it is, I think, above the mark. For example, 1836, 1837, 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, being six years running, with as fine appearance of wheat as I ever grew, I did not average twenty-six bushels per acre, weighing 64 lb. to 65 lb. per imperial bushel, in these six years. I considered my loss equal to 2000 bolls wheat below a fair crop, all in consequence of the fly." – (JOHN THOMPSON, Craigie, Leuchars.)

"I have carefully looked over Mr Watson's statement, and I think that his calculations are very correct, and agree entirely with my experience, except in regard to the profits upon stock, which I think he has rather overrated, as the price of stock is falling every week. I do not think it necessary, however, to make out a separate statement." – (David Hood, Hatton, Glammis.)

"In reply to yours of the 8th instant, requesting my opinion as to the accuracy of the statements in your enclosed proof-sheet, I have to state that, after mature consideration, I generally concur with the statement drawn by Mr Watson as to the results; though, I think, that as a deduction of £20 per cent on the profits of livestock has been made in the free-trade account, a like percentage should be deducted from the amount stated for casualties in the charge, thus making the loss under free trade £20 less. It also appears to me, that both the capital invested, and the amount received for crop and stock, are considerably beyond the average of farming capital and proceeds in Strathmore and the eastern district of Forfarshire; but as the statement is headed as "under the improved system of agriculture," of course the amounts must be different, and therefore are acceded to.

"It may be remarked, that the depreciation of £20 per cent on the value of livestock, which has taken place this year, ought only to be deducted from the average of the last ten or twelve years, as the present prices might be considered equal to what we had been receiving previously to the opening up the southern markets.

"In my own case, the rent is considerably lower than that assumed, as I occupy a large proportion of unequal, inferior soil, which I have drained at my own expense; and, in order to raise the same quantity of grain per acre as mentioned in the statement, I have hitherto had to pay at least £100 more for manure than what seems to be allowed for under the title 'expenses of management.'" – (William Ruxton, Farnell, Brechin.)

"I received yours of the 8th, with the enclosed statements regarding the prospects of agriculture, and as this was a ploughing-match day, (the Buchan district,) I deferred writing you until I should also show it to several experienced farmers for their opinions, and we all consider the statements as near as may be correct." – (John Hutchison, Monyruy, Peterhead.)

"I have examined minutely the statements drawn up by Messrs Watson and Dudgeon, and have compared them with some calculations that I had previously made myself, and have no hesitation in allowing my name to be affixed to them as attesting their accuracy, in so far as my knowledge of the localities in which they are drawn up leads me to be a judge. Had I had time, I should have liked to have furnished you with a similar comparative statement of the difference likely to be made by free trade in our more northern climate, where we cannot raise the same quality of grain, and where little or no wheat is grown, and I am much afraid it would not have been so favourable to farmers as Messrs Watson and Dudgeon's are. The average price of what has been sold of this year's crop, in the counties of Aberdeen and Banff, is not more, I am sure, than 1s. 8d. per bushel for oats, and 2s. 6d. for bear or barley." – (Robert Simpson, Cobairdy, Huntly.)

"As to the statements of Messrs Watson and Dudgeon, the items appear to me, on the whole, to be fairly put. My only difficulty is in regard to the £3000 put down in Mr Watson's statement as invested capital. I presume, however, he includes in this draining and lime sunk, machinery, implements, horses, &c.; and, considering the valuable breed of cattle and sheep on the Keillor Farm, I would not regard £5000 as at all too large an estimate for capital of both kinds. As to the considerable difference in profits shown in Nos. I. and II., that might be accounted for in many ways. In 500-acre farms, with equal management and a like rent, greater differences will be induced by variations in the soil and climate alone.

"On the presumption above stated, as to what Mr Watson means by invested capital, I have no difficulty in allowing you to affix my name, as attesting, to the best of my knowledge, the substantial accuracy of statements Nos. I. and II." – (William M'Combie, Tillyfour, Aberdeen.)

"I have gone over the respective statements with much care and anxiety, and have compared the different items entered to the debit and credit of the farm by both gentlemen with my own experience in such matters, and, on the whole, I have no hesitation in pronouncing them as nearly correct as, under the circumstances, they could be framed. Were I to draw up a statement of a farm of the like extent in this county, I believe the result would be still less favourable for the farmer, because if we have such returns as are stated by Messrs Watson and Dudgeon, we obtain them by the application to our land of a larger quantity of foreign manure than those gentlemen seem to use." – (Peter Brown, Linkwood, Elgin.)

Some of the gentlemen to whom we wrote, whilst entirely concurring in the estimates of Messrs Watson and Dudgeon, have not authorised us to affix their names. Only three gentlemen, out of nearly fifty, have refused their assent on the ground of difference of opinion. The most important objection specified by any of them was, that the prices of grain assumed in No. II., as having been received before protection was withdrawn, were higher than those warranted by the fiars' prices of the county. Such were, however, the actual prices received in those years by Mr Dudgeon; and the reader is requested to refer to the extract from Mr Nisbet of Lambden's letter for a corroboration as to that point. That there should be some difference of opinion is only natural, when the variations of soil, climate, and locality are considered; but we think it will generally be admitted, that the ordeal to which these estimates have been exposed, without exciting more challenge than we have just noticed, is a tolerably convincing proof of their general accuracy.

The receipt of these statements has induced several gentlemen, in different parts of the country, to draw up further estimates of the working of farms in their own districts, and these documents we now proceed to lay before our readers —

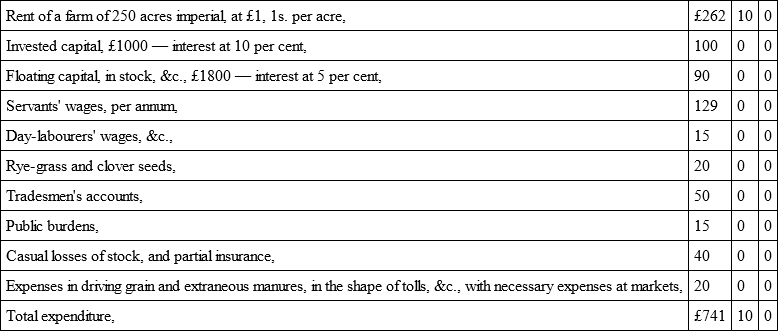

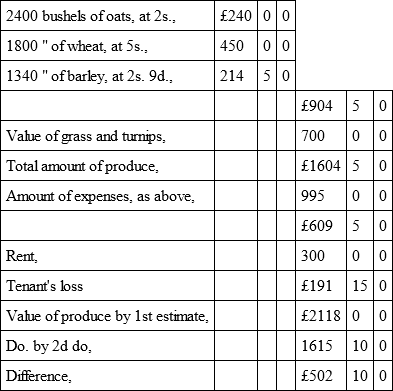

No. IIIStatement of Income and Expenditure on an Aberdeenshire farm of the ordinary description, taking the value of produce at an average of a series of years – say 19 – previously to the late alteration of the law in relation to the importation of corn and cattle. – Extent, 250 acres.

Annual Expenditure.

250 acres, on the five-course rotation: —

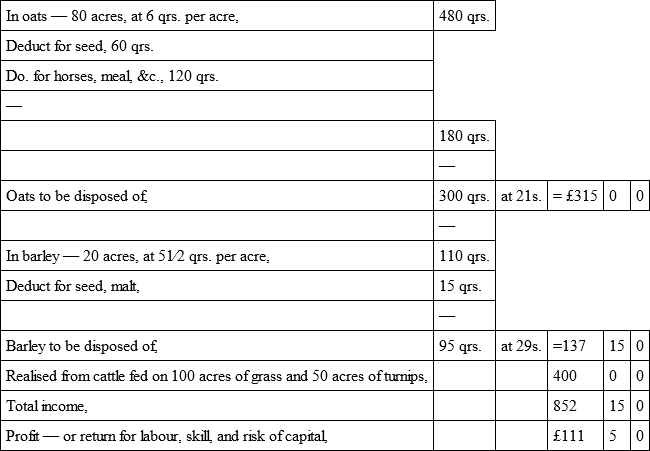

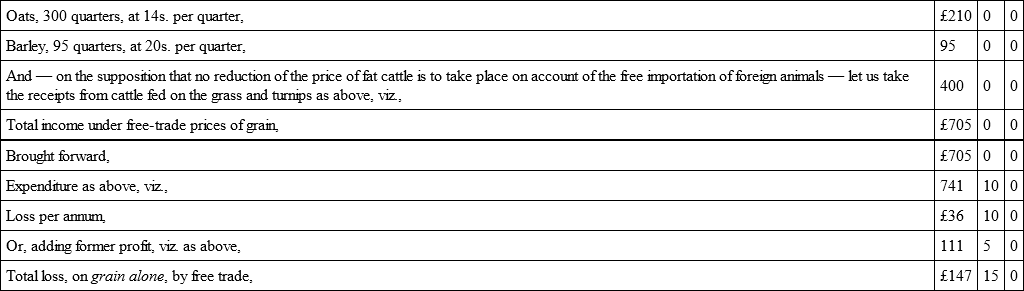

Income under Free-trade Prices.

I consider the above a fair statement of the expenditure and income on a farm in the lower district of Aberdeenshire, under former and under present circumstances. It will be observed that no wheat is grown; but the soil is well adapted for the rearing and feeding of cattle, and from this source the Aberdeenshire farmer expects to derive a large proportion of his returns. In the comparison, reference is had solely to the fall in the price of the kinds of grain cultivated. Whatever decline in the price of fat cattle may arise from free trade, will fall heavily on the farmers of this district; and the reduction of income thus occasioned will, of course, add to the amount of loss shown above.

JAMES HAY,Little Ythsie, 13th December 1849.Having lately had an opportunity of examining a number of actual accounts of income and expenditure on various farms, I can confirm the substantial accuracy and fairness of the above statements, Nos. I. and II. Mr Hay's statement above, referring to the system of agriculture with which, in this part of the country, we are most conversant, may, in my humble opinion, be regarded as fair and just, and as near the average that a comparison of a number of individual cases would indicate, as it can be made.

I am sensible that, in many cases of calculations – more especially in those in which certain assumptions have to be made – it is quite possible, even with a show of fairness, to bring out by means of figures almost any result that may be desired; but it is to be observed that, in the above statements, the same assumptions (if they can be regarded as such) are made on both sides of the comparison, with the exception of the prices at which agricultural produce is taken; and it is submitted with confidence that these are neither made higher in the one case, nor lower in the other, than experience warrants.

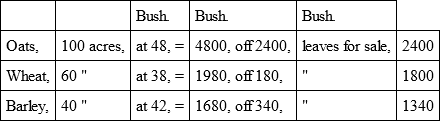

W. HAY,Tillydesk, 14th December 1849.No. IVEstimated Value, of the produce upon a farm in Roxburghshire of 500 acres, managed according to the five-shift rotation, thus: —

200 acres of corn crop.

200 " of grass.

100 " of turnips.

–

500

It is here assumed that there are no local advantages, the whole green crops being consumed upon the farm by sheep and cattle.

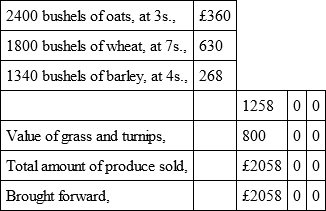

I. Produce of Corn Crops.

Average Value during the ten years preceding Crop 1848.

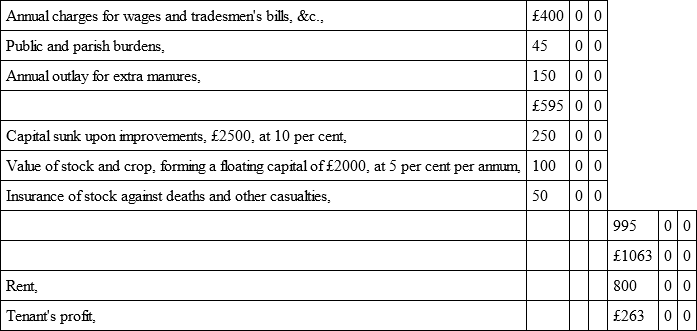

Expenses and Rent —

Estimated Value of the same amount of produce at the present rate of prices: —

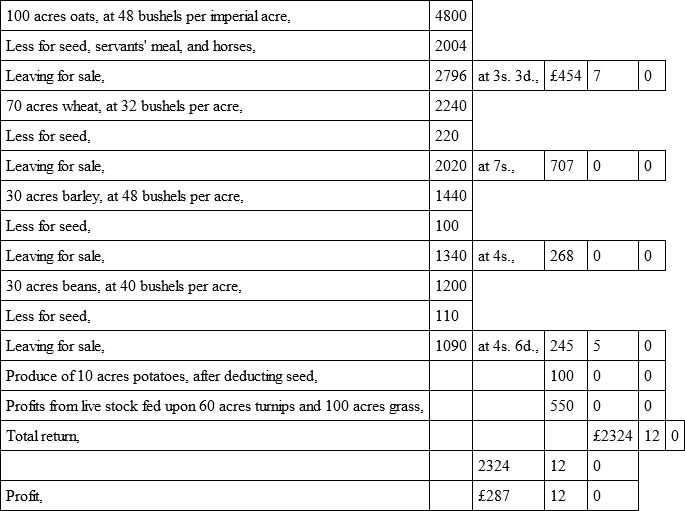

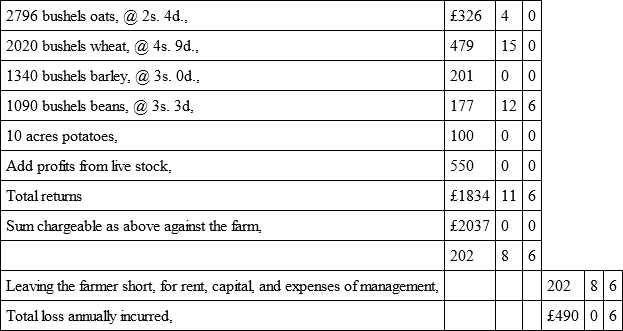

The total amount of capital invested is £4500, of which £2500 is sunk upon improvements. According to the first estimate, the annual return, exclusive of 5 per cent per annum for repayment of the sum sunk, would be £548, or at the rate of about 121⁄5 per cent. According to the second estimate, the annual return would be £45, 10s., or at the rate of about 1 per cent per annum upon the same sum.

I shall be glad to allow my name to be affixed to Mr Dudgeon's statement, as attesting, in so far as my experience goes, the accuracy of it.

My estimates and his very nearly correspond; but as every one has his own method of making up such statements, I take the liberty of handing along with it this detail of my own.

In all, excepting in regard to the value of live stock, or produce of grass and turnips, we nearly agree; and this difference may be accounted for, because no part of farm produce varies so much in its return as that of the live stock. Upon such a farm as that which is taken as an example, sheep and cattle are not wholly reared upon the farm, but part are bought in to fatten; hence the returns depend upon three circumstances, – 1st, upon the crops of turnips and grass being less or more abundant; 2d, upon the price of lean stock; and, 3d, upon the price of fat. While, therefore, the butcher market may be very high, the feeder may not necessarily be well paid, – and hence, in making up returns under this head, a correct average is not easily ascertained; and as there must always be a difference of opinion among practical men upon this part of the subject, I think, for publication, Mr Dudgeon's method of stating the returns in one sum is preferable to giving them in detail.

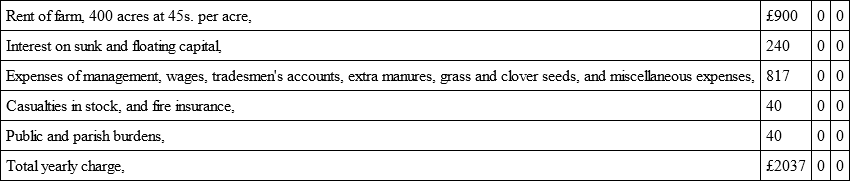

JAS. ROBERTON,Ladyrig, 13th Dec. 1849.No. VStatement of the Annual Charge against, and Returns from, a 400 imperial acre Farm in Mid-Lothian – on an average of ten years previous to free trade in corn and cattle; – with a comparative statement of the Returns of Produce from the same farm under the present free-trade measures affecting agriculture. The farm alluded to is managed on the four-course shift – the whole straw, turnips, and clover being consumed on it, and an average number of stock fattened.

To meet this sum there is the produce of 230 acres corn crop, 10 acres potatoes, and the profits from live stock as follows: —

The like quantities of disposable grain, taken at the present prices, fetch as follows: —

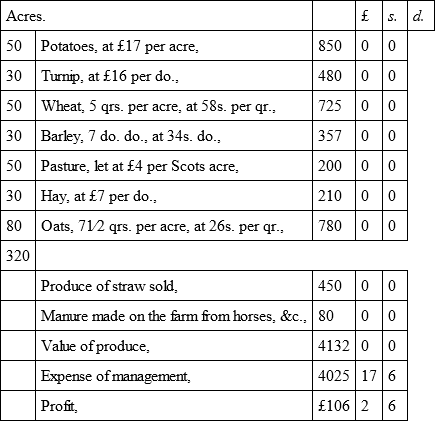

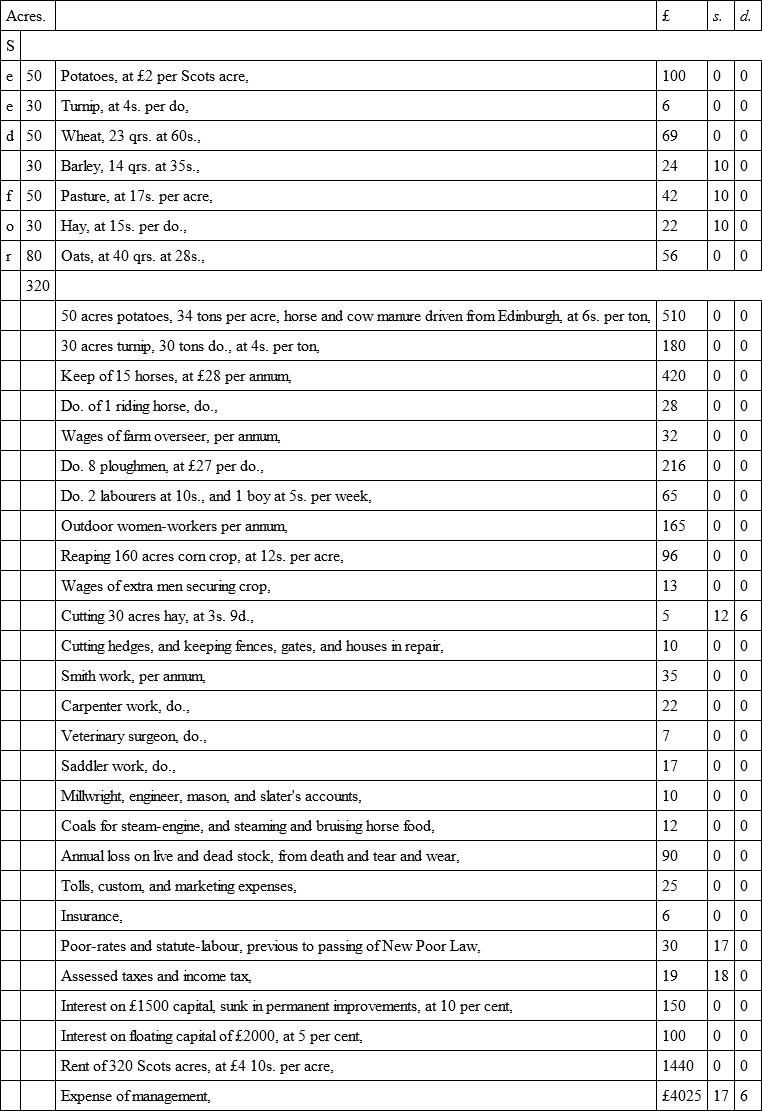

Valuation of Produce, and Expense of Management of a Farm of 320 Scots acres, situated within five miles of Edinburgh, on an average of seven years previous to potato failure in 1846, and farmed according to the four-shift rotation, the straw being sold in Edinburgh, and dung bought. The produce is a fair average of the best-managed farms within five miles of Edinburgh, during the period from which the average is taken. The prices noted are what were realised, being about 3s. 6d. per qr. above the average prices of the county, and the expense of management charged is what was actually paid.

[We ought, perhaps, to explain that this case is peculiar. It is that of a first-class farm in the neighbourhood of Edinburgh, attested by men of the same standing as its tenant, and similarly situated; the average of the produce is very high, and the rent corresponding. Mr Gibson, the tenant farmer, has taken the details of the following statement from his books; so that it becomes of much value, as showing the statistics of farming in the immediate vicinity of the metropolis of Scotland. In estimating the productiveness of this farm by the extent of the yield, our English readers must bear in mind, that it is divided by the Scots and not the imperial acre as in the other estimates, the former being one-fifth larger. It will be allowed, on all hands, that the yield of this farm is extraordinary.]

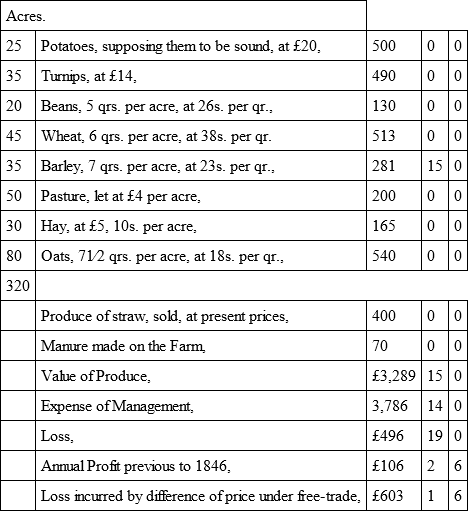

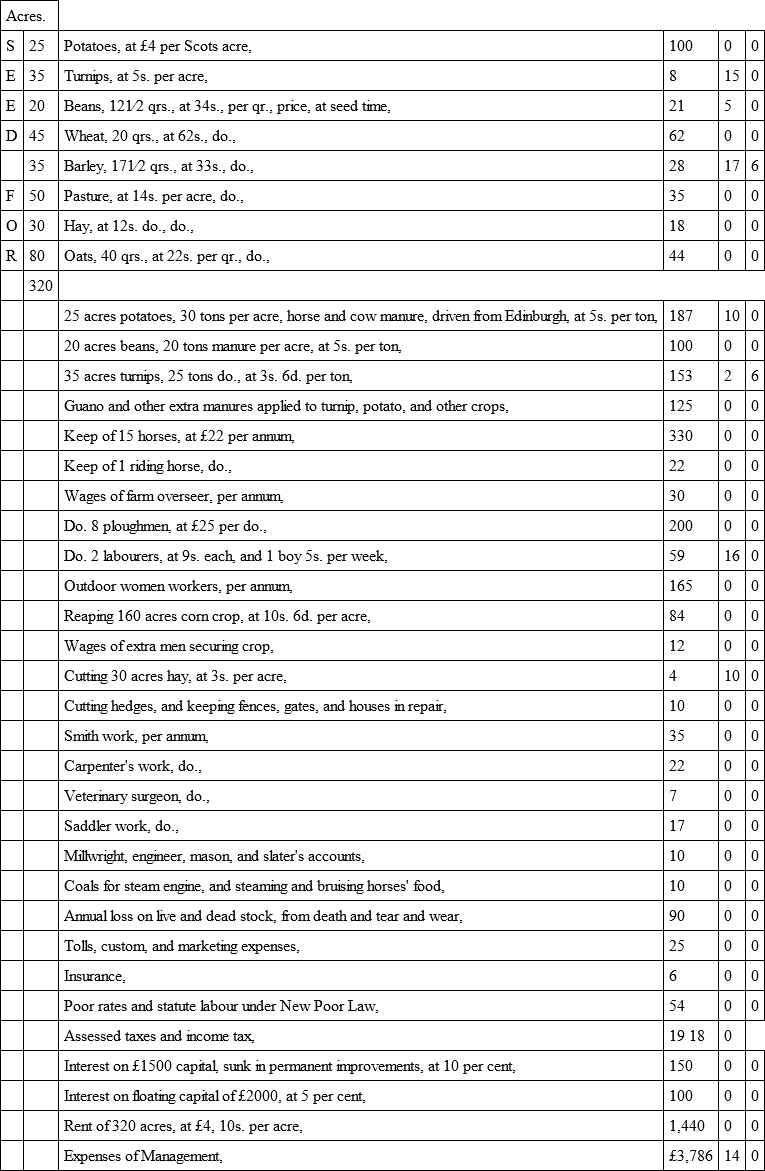

Valuation of Produce and Expenses of Management of the same Farm, for Crop 1849: as the Wheat crop is considered to be the best we have had in the district since 1835, every allowance is made for this in estimating the produce. The Oat, Barley, and Bean crops are under an average, but are charged at average quantities; the prices noted are what are being realised. In the expense of management full allowance is made in every item affected by present prices, except the seed, which is charged as paid for at seed time: had it been charged at present prices, there would fall to be deducted from expense of management a sum of £28.

Let those who believe that, by high farming, the soil can be stimulated so as to produce enormously augmented crops, at a large additional profit, consider the above statistics well. They are the statistics of the very highest farming in Scotland. The English agriculturist has been taunted for his backwardness in not adopting the improvements of his northern neighbour, who, with a worse climate, has made the most of the soil. Such has been the language used by some of the advocates and apologists of free trade, who are now urging the farmer to lay out more capital in draining and manures – assuring him that, by doing so, the returns will far exceed the interest of the outlay. With a fine disregard for the elements of arithmetic, they insist that low prices can in no way interfere with his success, and that only exertion and enterprise are wanting to raise him above the reach of foreign competition. The above tables exhibit the experiment, worked out to its highest point. In these cases capital has been liberally expended, energy tasked to the utmost, and every means, which science can devise or experience suggest, called into active operation. The farmers of Mid-Lothian, Berwickshire and Forfarshire may fairly challenge the world in point of professional attainments. They have done all that man can do, and here is the reward of their toil.

Supposing, then, that hereafter the permanent price of wheat were to be 40s. a quarter; that other cereal produce remained at corresponding rates; and that the value of live stock did not diminish – points, upon all of which we are truly more than sceptical – it will follow that high farming, such as is at present practised in the best agricultural districts of Scotland, cannot by possibility be carried on. No possible reduction of rent would suffice to enable the farmer to continue his competition. Such a fall must necessarily have the effect of annihilating one of the two classes; for the landlord, burdened as he is, would cease to draw the means of maintenance from his estate, and it is questionable whether the residue would suffice to pay the interest of the mortgages and preferable burdens. To the people of Scotland this is the most vital question that has engaged their attention since the Union. Our national prosperity does not depend upon manufactures to the same degree as that of England. By far the greater portion of our wealth arises directly from the soil: by far the larger number of our population depend upon that for their subsistence. Even if Manchester statistics were applicable to England, the case is different here. If the prices of agricultural produce should continue as low as at present – and we cannot see what chance exists of their rising, in the face of such a tremendous import – the effect upon this country must be disastrous. Such prices would reduce Scotland, at one fell swoop, to the condition of Ireland: paralyse the home market for manufactures; throw hundreds of thousands out of employment; lower the revenue; augment the poor-rates; and utterly disorganise society. And yet what help for it? The farmer cannot be expected to pay for the privilege of losing several hundreds per annum by cultivation. Let Mr Watson's statement be examined, and it will appear that the enterprising and skilful tenant of a farm of five hundred acres, in the best corn district of Forfar, cannot clear his expenses unless the rent of the land is reduced by one-half, and, even if that were done, he could only realise a profit of sixpence per acre! Such a result, we fairly allow, would appear, at first sight, to be incredible; yet there it is – vouched for by men of name, character, and high reputation. This is the extreme case; but, if we pass to Berwickshire, we shall find that a reduction of half the rent would barely place the tenant in the same position which he occupied previous to the withdrawal of protection. Look at No. IV., and the result will appear worse. Even were one half of the rent remitted, the profits of the tenants, at present prices, would be less by £100 than they were at the former rates of corn. Very nearly the same results will be brought out, if we calculate the necessary reductions on the rents of the Mid-Lothian farms. Lord Kinnaird may see in those tables the fate which is in store for him; and he cannot hope to escape it long, even by inserting, in his new leases, the most stringent stipulations as to money payments which legal ingenuity can devise. It is just possible that "men of business habits," retired shopkeepers, and others of that class, may be coaxed and persuaded into trying their hands at a trade of which they know literally nothing. They may be incautious enough to put their names to covenants, not conceived according to Mr Caird's liberal principle, and so pledge their capital for the fulfilment of a bargain which common sense declares, and experience proves, to be preposterous. The necessary consequence will be, that the rent must be paid out of capital, a process which cannot last long; and the unhappy speculator, as he finds his earnings disappearing, will curse the hour when he yielded to the delusion, that high farming must be profitable in spite of the variations of price. The poor seamstress, who weekly turns out of hand her augmented number of improved shirts – and who lately, though on exceedingly erroneous principles, has found a warm advocate in the kind-hearted Mr Sydney Herbert – has, in her own way, tested the value of the experiment. There is more cotton to be shaped, and more work to be done, but the prices continue to fall. She makes two additional shirts, but she receives nothing for the additional labour, because the remuneration for each is beaten down. The free-trade tariffs are the cause of her distress, but the unfortunate creature is not learned in statistics, and therefore does not understand the source of her present misery. No more, probably, do the female population of the Orkney islands, whom Sir Robert Peel reduced to penury some years ago, by a single stroke of his pen, through the article of straw-plait. From Lerwick to the Scilly Isles, the poor industrious classes were made the earliest victims. The tiller of the land is liable to the operation of the same rules. By the outlay of capital, he forces an additional crop, but, the value of produce having fallen, his returns, estimated in money, are just the same as before. If the maintenance of rents throughout the United Kingdom depends simply upon the supply of dupes, we are afraid that the Whig landlords will speedily find themselves in a sorry case.