Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 391, May, 1848

The fact is, that the farmers and all the lower classes care little for education per se, though they wish their children to profit by a knowledge of English, in order to facilitate their advancement in after life; and they are unwilling, at the same time, to support schools in connexion with the Church. That Church is to them the church of the rich man as distinguished from the poor; of the conqueror as distinguished from the conquered; of the Englishman as distinguished from the Welsh; it is the Church of England, not of Wales; and their affections as well as their prejudices are all opposed to it. This again is one of the main causes – and it is so pointed out by the commissioners – of the slow progress of education in Wales, supported, as it mainly is, by the upper classes. It is not the proper place to enter here into any further discussion as to all the causes of dispute in Wales; we will merely state that we believe it to be now confirmed, not only by the national antagonism of the two races, but also by the democratic principles which are so widely diffused throughout the country, and which are sure to break out again to a most dangerous extent in Wales on the first opportunity. Hear what Mr Lingen states on the subject: —

"Most singular is the character which has been developed by this theological bent of minds isolated from nearly all sources, direct or indirect, of secular information. Poetical and enthusiastic warmth of religious feeling, careful attendance upon religious services, zealous interest in religious knowledge, the comparative absence of crime, are found side by side with the most unreasoning prejudices and impulses; an utter want of method in thinking and acting; and (what is far worse) wide-spread disregard to temperance, wherever there are the means of excess, of chastity, of veracity, and of fair dealing. I subjoin two extreme instances of the wild fanaticism into which such temperaments may run. The first concerns the Rebecca riots. W. Chambers, jun., Esq. of Llanelly House, kindly furnished me with a large collection of contemporary documents and depositions concerning the period of those disturbances. An extract from the deposition of one Thomas Phillips of Topsail, is illustrative of the vividly descriptive and imaginative powers of the Welsh, and of the peculiar forms under which popular excitement among them would be sure to exhibit itself.

"Shoui-yschwr-fawr and Dai Cantwr were noms de guerre borne by two ringleaders in these disturbances.

"Between ten and eleven o'clock on the night of the attack on Mr Newman's house, I was called upon by Shoui-yschwr-fawr, and went with the party. On my way I had a conversation with Dai Cantwr. Thomas Morris, a collier, by the Five Cross Roads, was walking before us, with a long gun. I said "Thomas is enough to frighten one with his long gun." Dai said, "There is not such a free man as Tom Morris in the rank. I was coming up Gellygwlwnog field, arm in arm with him, after burning Mr Chambers's ricks of hay; and he had a gun in the other hand, and Tom said, "Here's a hare," and he up with his gun and shot it slap down – and it was a horse – Mr Chambers's horse. One of the party stuck the horse with a knife – the blood flowed – and Tom Morris held his hand under the blood, and called upon the persons to come forward and dip their fingers in it, and take it as a sacrifice instead of Christ; and the parties did so.' And Dai added, 'that he had often heard of a sacrament in many ways, but had never heard of a sacrament by a horse before that night.'

"The other instance was told me by one who witnessed much of the Chartist outbreak. He said that 'the men who marched from the hills to join Frost, had no definite object beyond a fanatical notion that they were to march immediately to London, fight a great battle, and conquer a great kingdom.' I could not help being reminded of the swarm that followed Walter the Penniless, and took the town which they reached at the end of their first day's march for Jerusalem."

We could point out several districts in Wales, in which few gentry reside, such as the south-western portion of Caernarvon, and some parts of Anglesey, where the most republican and levelling doctrines prevail extensively among the farmers and the labouring classes, and where resistance to tithes, and not only to tithes, but to rents, is a subject fondly cherished for future opportunity. The town of Caernarvon itself is a pestilent hot-bed of discontent; so is Merthyr Tydvil; so is Newtown; so is Swansea; and so are many others.

The commissioners dwell rather lightly on this part of the subject – on these consequences of the past and present condition of the country, and of the defective education existing in it. Many of the assistants employed by the commissioners were Dissenters, and their examinations of Church schools may be therefore suspected; at least we fancy that we can discern a certain warmth of admiration, and intensity of unction, in the reports on the Dissenting schools, which are not bestowed on the others. However this may be, we cannot but admit that these reports do actually show the existence of a very defective state of things in the principality; and we find the commissioners justly pointing out and reprobating two glaring vices in the Welsh character, the existence of which we admit, and to which we shall, of our own knowledge, add a third.

The first refers to the want of chastity, or rather to the lax ideas of the common order of people on that subject previous to marriage. This, with every wish to excuse the national feelings and failings of the Welsh, we must allow to be proved by the concurrent testimony and experience of every one well acquainted with the principality. This vice, however, is more systematically established in the northern than in the southern counties; and the existence of this system is, we have no doubt, of very long standing, ranking, indeed, among the national customs which lose their origin in the night of ages. The common notion prevalent among the lower classes in Wales, and generally acted on, is, that want of chastity before marriage is no vice, though afterwards it is considered a crime, which is very rarely committed. Before we pass a sweeping condemnation on the rude population of the Welsh mountains for this laxity, let us remember that, such is the false state of "over-civilisation" in England, the same ideas and practices exist universally among the male portion, at least, of the people, and pass without any thing beyond a formal, we might almost say, a legal reprimand: that in France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and, it may be, other countries of Europe, this laxity exists not so much before as after marriage; and that therefore the poor Celtic mountaineers do not stand alone in their ignorance of what is better.

It appears by the official returns, that the proportion of illegitimate children in North Wales shows an excess of 12·3 per cent above the average of all England and Wales upon the like numbers of registered births. We know ourselves of a union of 48 parishes in which there are now 500 bastard children supported out of the poor-rates; and, in fact, the prevalence of the vice is not to be denied. The volumes of these reports contain numerous minutes of evidences and letters from magistrates and clergymen corroborative of this fact; and they all agree in referring it to the ignorance of the people. We are not inclined to lift the veil which we would willingly allow to hang over the faults, the weaknesses, and the ignorance of a poor uncultivated people; believing, as we do, that the remedies for such a state of things are not far off, nor difficult to find; and knowing that, if there be any palliation of such a state of things, it is to be found in this circumstance, that the married state is most duly honoured and observed in that country, and also, that the women marry early in life, and support all the duties of their state in an exemplary manner. We could also pick out county after county in England, where we know that the morality of the lower orders is little, if at all, elevated above this standard, and where the phenomenon of the pregnant bride is one of the most ordinary occurrence. The statement of these facts, as published by the commissioners, has caused great indignation throughout Wales, and has set the local press in a ferment, but has not produced any satisfactory refutation of the impeachment.

Another vice, correlative to, and consequent upon the other, is the want of truth and honesty in petty matters observable throughout the land. This is the common complaint of almost every gentleman and magistrate in the twelve counties – that the word of a Welshman of the lower classes is hardly to be trusted in little matters; and that the crime of false swearing in courts and at quarter-sessions is exceedingly frequent. In the same manner, the people generally, in the minor transactions of life, are given to equivocations and by-dealing, and make light of telling an untruth if it refers only to a matter of minor importance. Were a Welshman called as a witness in a case of felony, we think his oath might be depended upon as much as an Englishman's; but is he called up on a case of common assault, or the stealing of a few potatoes from his neighbour's field – or is he covenanting to sell you coals or corn at a certain price and weight – we should be uncommonly careful how we trusted to his deposition or his assurances.

A clergyman of Brecknockshire says: —

"The Welsh are more deceitful than the English; though they are full of expression, I cannot rely on them as I should on the English. There is more disposition to pilfer than among the English, but we are less apprehensive of robbery than in England. There is less open avowal of a want of chastity, but it exists; and there is far less feeling of delicacy between the sexes here in every-day life than in England. The boys bathe here, for instance, in the river at the bridge in public, and I have been insulted for endeavouring to stop it. There is less open wickedness as regards prostitution than in England. Drunkenness is the prevailing sin of this place and the county around, and is not confined to the labouring classes, but the drunkenness of the lower classes is greatly caused by the example of those above them, who pass their evenings in the public-houses. But clergymen and magistrates, who used to frequent them, have ceased to do so within the last few years. I have preached against the sin, and used other efforts to check it, though I have been insulted for doing so in the street. I think things are better than they were in this respect… I do not think they are addicted to gambling, but their chief vice is that of sotting in the public-houses."

A magistrate, in another part of the county, gives the following testimony: —

"Crimes of violence are almost unknown, such as burglary, forcible robbery, or the use of the knife. Common assaults are frequent, usually arising from drunken quarrels. Petty thefts are not particularly numerous. Poultry-stealing and sheep-stealing prevail to a considerable extent. There is no rural police, and the parish constables are for the most part utterly useless, except for serving summonses, &c. Sheep and poultry stealers, therefore, very frequently escape with impunity. Drunkenness prevails to a lamentable extent – not so much among the lowest class, who are restrained by their poverty, as among those who are in better circumstances. Every market or fair day affords too much proof of this assertion. Unchastity in the women is, I am sorry to say, a great stain upon our people. The number of bastard children is very great, as is shown by the application of young women for admission into the workhouse to be confined, and by the application to magistrates in petty sessions for orders of affiliation. In hearing these cases, it is impossible not to remark how unconscious of shame both the young woman and her parents often appear to be. In the majority of cases where an order of affiliation is sought, marriage was promised, or the expectation of it held out. The cases are usually cases of bonâ fide seduction. Those who enter the workhouse to be confined are generally girls of known bad character. I believe that in the rural districts few professed prostitutes would be found."

The clerk, to the magistrates at Lampeter observes: —

"Perjury is common in courts of justice, and the Welsh language facilitates it; for, when witnesses understand English, they feign not to do so, in order to gain time in the process of translation, to shape and mould their answers according to the interest they wish to serve. Frequently neither the prisoner nor the jury understand English, and the counsel, nevertheless, addresses them in English, and the judge sums up in English, not one word of which do they often understand. Instances have occurred when I have had to translate the answers of an English witness into Welsh for the jury; and once even to the grand jury at Cardigan I had to do this. A juryman once asked me, 'What was the nature of an action in which he had given his verdict.'

"Truth and the sacredness of an oath are little thought of; it is most difficult to get satisfactory evidence in courts of justice."

Upon the above evidence, Mr Symons, the inspector, remarks: —

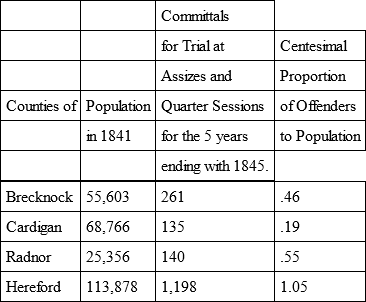

"Notwithstanding the lamentable state of morals, the jails are empty. The following comparison between the relative criminality of the three counties in my district with that of the neighbouring agricultural county of Hereford, exhibits this moral anomaly in the Welsh character very forcibly: —

"Crimes, therefore, are twice as numerous in Herefordshire as in Radnorshire or Brecknockshire, and five times more so than in Cardiganshire.

"I attribute this paucity of punishable offences in Wales partly to the extreme shrewdness and caution of the people, but much more to a natural benevolence and warmth of heart, which powerfully deters them from acts of malice and all deliberate injury to others. And I cannot but express my surprise that a characteristic so highly to the credit of the Welsh people, and of which so many evidences presented themselves to the eye of the stranger, should have been left chiefly to his own personal testimony. Facts were nevertheless related to me which bore out my impression; and I may instance the ancient practice among neighbouring families of assisting the marriages of each other's children by loans or gifts of money at the 'biddings' or marriage meetings, to be repaid only on a similar occasion in the family of the donor, as well as the attendance of friends at times of death or adversity, as among the incidents which spring from and mark this honourable characteristic."

Notwithstanding all this, we know, from official sources, that the proportion per cent of commitments for North Wales is sixty-one per cent below the calculated average for all England and Wales, on the same amount of male population of the like ages. In fact, the jails of Wales are commonly empty, or the next thing to it; and the whole twelve counties would hardly keep one barrister, on the crown side, above starving-point. Maiden assizes are any thing but uncommon in that country.

That particular foci of evil do exist, we have asserted before; and we find the following trace of this portion of the subject in the report of Mr Vaughan Johnson on Montgomeryshire: —

"The following evidence relates to the parishes of Newtown and Llanllwchaiarn, which contain 6842 inhabitants: —

'It appears that, previously to the year 1845, no district in North Wales was more neglected, in respect of education, than the parishes of Newtown and Llanllwchaiarn. The effects were partly seen in the turbulent and seditious state of the neighbourhood in the year 1839. The permanent evils which have sprung from this neglect it will require many years of careful education to eradicate. A memorial, presented by the inhabitants to the Lords of the Committee of Council on Education, at the close of the year 1845, contains the following plea for assistance in providing popular education: —

"In the spring of the year 1839 the peace of the town and neighbourhood was threatened by an intended insurrection on the part of the operative class, in connexion, it is supposed, with other parts of the kingdom, with a view to effect a change in the institutions of the country; but such an insurrection, if intended, was prevented by the presence of an armed force; and a military force has ever since been stationed in the town, with a view of preserving its peace.

'Your memorialists believe that, if the inhabitants had had the benefit of a sound moral and religious culture in early life, the presence of an armed force to protect the peace of the town would not be needed in so comparatively small a place; and your memorialists are under a firm conviction that no better way can be devised for the removal of all disposition to vice and crime, than by enlightening the ignorant, and especially by sowing in early life, by the hands of the teacher, the seeds of religion and morality.'"

'The alarm occasioned by these disturbances has passed away; but I ascertained, by a careful inquiry among the persons best acquainted with the condition of the working-classes, that even at the present day low and unprincipled publications, of a profane and seditious tendency, are much read by a class of the operatives; that private and secret clubs exist for the dissemination of such writings, by means of which the class of operatives have access to the writings of Paine and Volney, to Owen's tracts, and to newspapers and periodicals of the same pernicious tendency. It is stated that many persons who read such works also attend Sunday schools, from their anxiety to obtain a knowledge of the art of reading, which they cannot otherwise acquire. It is the opinion of those who are best acquainted with the evils complained of, that the most efficacious remedy would be the circulation of intelligent publications on general subjects, within the comprehension of the working-classes, by the help of reading-societies and circulating libraries, at terms which the operatives would be able to afford.'"

The third vice – for it is a vice – which we know to be prevalent in Wales, is the extreme dirt and untidiness of all the inhabitants. Go into any Welsh town or village, and observe the squalid shabby look of the houses and their tenants; visit their farms and cottages, and see the wretched filth in which men and animals herd together, and you will bear witness to the truth of our assertion. There is no spirit of order and improvement among them; every thing is done on the principle of the least possible present trouble. Were the Welsh blessed with the climate of Naples, they would, every one of them, become pure Lazzaroni, – as it is, they approximate to the Irish in their innate indolence and love of dirt. Whenever the commissioners for the health of towns receive their full power, they will have an Augean stable to cleanse, comprising the whole Principality.

Even here, however, we are disposed to find some excuse for the people. They have so few resident gentry, at least of the larger proprietors; their country is so wild and so lonely; the difficulties of poverty and bad weather which they have to contend against are so great, that the philanthropical inquirer must make large allowances for them on this head. The commissioners found most of the country schools conducted in the most wretched buildings; but perhaps these buildings were some of the very best and cleanest in the district: they thought them neglected, and in bad repair; whereas the inhabitants might have supposed that they "had done the correct thing," and had adorned them in a style of lavish expenditure.

We might go on multiplying our extracts and our comments ad infinitum, but we purposely abstain; and we shall conclude our review of these highly important documents with one or two inferences that seem to us obviously necessary.

In the first place, as long as the Welsh language cannot reckon, among its literary treasures, the principal portion of the good elementary books of instruction which have long been employed in England, and are still issuing from the English press, it is obviously impossible to place the education of the Welsh on the same level as that of their Saxon neighbours. Not only should the best English books be translated into Welsh – we mean for the instruction and amusement of the middle and lower classes, – but translations might be made most advantageously from other tongues; and the literature of Wales might become permanently enriched with the best fruits of all nations. We by no means coincide in opinion with those who would discourage the study of Welsh, and would even attempt to suppress that language altogether; we look upon it as one of the most interesting and valuable, though not one of the most fortunate and gifted, of European tongues. In ancient literature, in poetry, and in an immense mass of oral tradition, it is uncommonly rich, and, by the mere dignity of age, is worthy of its place being ever kept for it among the languages of the world. But, further than this, though it operates to a certain extent as a social bar to the more intimate connexion of the Welsh and English populations, it serves also as a strong bond and support of Welsh nationality, and keeps alive in their breasts that indomitable love of their country, and that spirit of national pride, which is the best safeguard of the liberties of the realm, and its protection from democratic invasion. It hinders the operations of centralisation – that odious and destructive principle of government which Whigs and Democrats are so fond of copying from their masters, the revolutionary French; and it teaches the people to rely on their own resources, and to preserve the ancient freedom of their country. In times like these, when the aggressive levelling spirit of democracy is actively at work, and when the ancient liberties of the country are gradually falling beneath the scythe of radical innovation, any thing that may serve as a check to the decline and fall of the empire is not to be lightly despised or abandoned. The Welsh, like the Basques, like the Bretons, like the Hungarians, have preserved their national language and feelings, though all these are united to empires and people far more powerful and numerous than themselves; and thus are destined to form the most energetic and abiding portions of those empires, when the excessive advance of civilisation, and the destruction of all national virtues, shall have brought about their disruption and ruin. Let the higher orders and the government of the country show, the former more enlightened and more energetic patriotism, and the latter more intelligence and foresight than hitherto. Let them provide the people with the materials of education and instruction; let them call forth the numerous learned men to be found amongst the clergy of the Principality; let them require and pay for the formation of an elementary literature, and the nucleus thus originated will grow betimes into a goodly mass, fit for the work required, and itself generating the means of its future increase. The natural acuteness of the Welsh people is such – and the Commissioners bear ample testimony to the fact – that, had they but books in their own tongue, the facts of knowledge would be universally acquired. They would make as much progress in secular as they now do in theological research; and were their powers of acquisition well directed, the whole character of the nation would undergo an elevating and improving change.

We would have them taught English as a foreign language – as an accomplishment, in fact. It belongs to a totally different family of languages, and must always be a foreign tongue to a Celt – but still it may be acquired sufficiently for all the common purposes of life; while all facts, all instruction, all matters for reflection and memory, should be conveyed in the national tongue, the pure Cymric language.

Government need not trouble itself by attempting to carry the details of educational systems into operation; all that it is required to supply is the moving and the controlling power; the various duties of the great machine will be better fulfilled by the people at large – that is to say, by the local authorities, the constituted voices and hands of the national body.