Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 391, May, 1848

Lord Brougham, a great liberal authority in his day, has given, in the House of Peers, the following graphic and characteristic account of the state of France at this time, (April 17,) from which he has just returned: —

"The present condition of Paris, if it continue for any time, would inevitably effect the ruin of that glorious country. Paris governs France, and a handful of the mob govern Paris. He hoped and trusted that they would live to see better times. He hoped that what they now saw passing before their eyes – the general want of credit, the utter impossibility of commerce going on, the complete ruin of trade in the capital and great towns, the expedients to which the Provisional Government finds itself compelled to have recourse day by day to perpetuate its existence, and to make its ephemeral being last – one day taking possession of the banks of deposit to the robbery of the poor – another, stopping the supplies of the rich – a third day stopping travellers for the purpose of taking their money from them (hear, hear, and laughter) at the barriers, upon the ground that the town was in want of cash. He hoped, he said, that they would soon see such an unsettled state of things give way to a more firm form of government. He knew some of those individuals who had severely suffered by these circumstances – (hear, and laughter) – but he should inform their Lordships that he was not here present. (Continued laughter.) Although it was a pity to spoil their merriment, he yet rejoiced in being able to show them that there was not a shadow of foundation for the report which had been circulated respecting himself; when he came to the barrier, the circumstance occurred which had no doubt given rise to the story. He was told that he should stop in order that his baggage might be examined. On requiring further explanation for this conduct, he was informed that the inquiry was sought for for the purpose of seeing whether he had any money. (Laughter.) He had heard a great deal respecting the misgovernment of former rulers, but he had never heard of such a step as this being tolerated. He knew one person from whom they took 200,000 francs, giving him bank paper instead. The state of trade in that country was dreadful – the funds falling suddenly from 70 to 32; the bank stopping, notwithstanding the order for the suspension of cash-payments; the taking possession of one of the railways, with the proceeds, amounting to about £8000 a-week, which were put into Louis Blanc's pocket to be dispensed again according to his peculiar theory. In the same way, it was said, the Provisional Government intended to act with all the other railways. They had, no doubt, a right to do all this, if they pleased, and also, as it was rumoured they intended to do, to seize the bank, and to issue a paper currency to a very large amount. He only hoped that at the meeting of the National Assembly, they would open their eyes to the necessity of taking such steps as to prevent that mischief to which such experiments as these were likely to lead. (Hear, hear.) He believed that the certain result of such a government would be this – that they would be stricken down with imbecility, and would become too weak to perform the ordinary functions of a government. They might struggle on for a time, until some military commander would rise and destroy the Republic, and perhaps plant in its place a military despotism. At this moment he was of opinion that any one general, with 10,000 men, marching into Paris, would have the effect of at once putting an end to the Republic. No man could doubt it. The Belgian ambassador the other day had applied to M. Lamartine for protection; the latter said in reply, he admitted the full right of the ambassador to such protection, but he had not really three men at his disposal. The people in Paris were as uneasy as any persons could be at this state of things, but they have made up their minds to the fact that this experiment of a Republic must be tried; so that France must remain a Republic for some time, whether it be for her advantage or not." —Morning Chronicle, April 13, 1848.

Wretched as this account of the present state of France is, its prospects are if possible still more deplorable. The misery brought on the working-classes by the ruin of commerce, destruction of credit, and flight of the opulent foreigners, is such that it is absolutely sickening to contemplate it. Seventy-five thousand persons are out of employment in Paris alone, which, with the usual number of dependents, must imply two hundred thousand human beings in a state of destitution. The only way of supporting this enormous mass of indigence is by maintaining it as an armed force; and it is said that 200,000 idlers are in this way paid thirty sous a-day to keep them from plundering the capital! But the resources of no country, far less one shipwrecked in capital, trade, and industry, can withstand such a strain. The following is one of the latest accounts of the financial and social condition of France, by an able observer on the spot: —

"The time is now fast approaching when the pecuniary resources left in the treasury at the revolution will be exhausted. The old loan has ceased to be paid up. The new loan remains a barren failure. The regular taxes are paid with reluctance, and are not paid beforehand except in Paris. The additional impost of 45 centimes (near 50 per cent on the direct taxes) is positively refused as illegal by the rural districts and provincial cities. The stock of bullion in the Bank of France decreases, and, in short, the progress of financial ruin goes steadily on. We pointed out some weeks ago the exact and inevitable course of this decline, and we now read in a French journal of repute the precise confirmation of our predictions: – 'We are now,' says the Journal des Debats, 'but two steps removed from a complete system of paper-money; and if we enter on that system, we shall not get out of it again short of the total ruin of private persons and of the state, after having passed through the most rigorous distress; for it would be the suspension of production and of exchange.' The plan proposed, though not yet sanctioned by the Provisional Government, seems to be a general seizure and incorporation with the state of all the great financial and trading companies, such as the Bank of France, the railways, the canals, mines, &c., and the issue of a vast amount of paper by the state on the alleged credit of this property – in short, a pure inconvertible system of assignats. Monstrous as such a proposal appears, we are inclined to think that the rapid disappearance of the precious metals will render some such scheme inevitable, and it will be the form given to the bankruptcy and ruin of the nation." —Times, 14th April.

In the midst of these woful circumstances, the Provisional Government does not for a moment intermit in the inflaming the public mind by the most fallacious and false promises of boundless future prosperity from the adherence to republican principles, and the return of stanch republicans to the approaching assembly. In the same able journal it is observed, —

"We have now before us a handbill entitled the Bulletin de la Republique, and printed on white paper, the distinctive mark of official proclamations, headed, moreover, with the words "Ministère de l'Intérieur." This document is one of those semi-officially circulated, as we understand, by M. Ledru Rollin, for the purpose of exciting the Republican party. A more disastrous appeal to popular passions, and a more delusive pledge to remedy all human sufferings, we never read; for after having laid to the charge of existing laws all the miseries of a poor man's lot, heightened by inflammatory description, the working classes are told that 'henceforth society will give them employment, food, instruction, honour, air, and daylight. It will watch over the preservation of their lives, their health, their intelligence, their dignity. It will give asylum to the aged, work for their hands, confidence to their hearts, and rest to their nights. It will watch over the virtue of their daughters, the requisite provision for their children, and the obsequies of the dead.' In a word, this exceptional and transitory power, whose very form and existence are still undefined, announces some necromantic method of interposing between man and all the laws of his existence on this globe – of suspending the principles of human nature, as it has already done those of society – and of changing the whole aspect of human life. No delusions can be so enormous: the word is too good for them —they are frauds; and these frauds are put forward by men who know well enough that the effect of the present crisis already is, and will be much more hereafter, to plunge the very classes to whom these promises are made into the lowest depths of human suffering." —Times, 14th April.

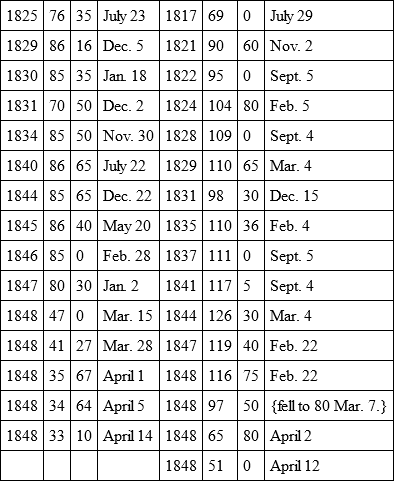

One of the most instructive facts as to the ruinous effect of the late Revolution on the best interests of French industry, is to be found in the progressive and rapid decline in the value of all French securities, public and private, since it took place. It distinctly appears that two-thirds of the capital of France has been destroyed since the Revolution, in the short space of six weeks! Attend to the fall in the value of the public funds during that brief but disastrous period: —

La Presse, March 12, and Times since that date.

The value of railway stock and bank shares has declined in a still more alarming proportion. Bank shares, which in 1824 sold for 3400 francs, are now selling at 900 francs – or little more than A FOURTH of their former value. Railway stock is unsaleable, being marked out for immediate confiscation. Taking one kind of stock with another, it may safely be affirmed that TWO-THIRDS of the capital of France has perished since the Revolution, in the short space of seven weeks. The fruit of thirty-three years' peace, hard labour, and penurious saving, has disappeared in seven weeks of anarchical transports!! Of course, the means of employing the people have declined in the same proportion; for where credit is annihilated, how is industry to be maintained, before its produce comes in, but by realised capital? How is its produce to be disposed of if two-thirds of the classes possessed of property have been rendered bankrupt? Already this difficulty has been experienced in France. The Paris papers of 13th April announce that seventy-five thousand persons will be employed at the "ateliers Nationaux," or public workshops, at 30 sous a-day, in the end of April – at a cost of 112,500 francs a-day, or 3,375,000 francs, (£150,000) a-month. This is in addition to an armed force of above 100,000 men, paid for the most part two francs a-day for doing nothing. No exchequer in the world can stand such a strain; far less that of a bankrupt and revolutionised country like France. It is no wonder that the French funds are down at 32, and an issue of assignats – in other words, the open and avowed destruction of all realised property – is seriously contemplated.

This is exactly the condition to which France was brought during the Reign of Terror, when the whole inhabitants of Paris fell as a burden on the government, and the cost of the 680,000 rations daily issued to them, exceeded that of the fourteen armies which combated on the frontiers for the Republic. In those days the misery in Paris, the result of the Revolution, was so extreme, that the bakers' shops were besieged day and night without intermission by a famishing crowd; and the unhappy applicants were kept all night waiting during a severe frost, with a rope in their hands, and the thermometer often down at 5° Fahrenheit, to secure their place for the distribution when the doors were opened. There is nothing new in the condition of France and Paris at this time: it has been seen and experienced in every age of the world; it has been familiar to the East for three thousand years. The principle that the state is the universal proprietor, the middle class the employés of government, and the labouring class the servants of the state, is exactly the oriental system of government. It is just the satraps and fellahs of Persia – the mandarins and peasants of China – the zemindars and ryots of Hindostan over again. Exact parallels to the armed and insolent rabble who now lord it over Paris, and through it over France, may be found in the Prætorians of Rome – the Mamelukes of Egypt – the Janissaries of Constantinople. The visions of perfectibility and utopian projects of Louis Blanc, Lamartine, and Ledru Rollin, have already landed the social interests of France in the straits of the Reign of Terror – its practical government in the armed despotism of the Algerine pirates, or the turbulent sway of the Sikh soldiery.

But the contagion of violence, the ascendant of ambition, the lust of rapine have not been confined to the armed janissaries of Paris, or their delegates the Provisional Government. They have extended to other countries: they have spread to other states. They have infected governments as well as their subjects; they have disgraced the throne as well as the workshop. Wherever a revolution has been successful, and liberal governments have been installed, there a system of foreign aggression has instantly commenced. The first thing which the revolutionary government of Piedmont did, was to invade Lombardy, and drive the Austrian armies beyond the Po; the first exploit of constitutional Prussia, to pour into Sleswig to spoliate Denmark. Open preparations for revolutionising Lithuania are made in the grand-duchy of Posen. A war has already commenced on the Po and the Elbe; it is imminent on the Vistula. Lamartine's reply to the Italian deputation proves that France is prepared, on the least reverse to the Sardinian arms, to throw her sword into the scale; his conduct in permitting an armed rabble to set out from Paris to invade Belgium, and another from Lyons to revolutionise Savoy, that the extension of the frontier of France to the Rhine and the Alps is still the favourite project of the French republic. If he declines to do so, the armed prætorians of Paris will soon find another foreign minister who will. France has 600,000 men in arms: Austria 500,000: 150,000 Russians will soon be on the Vistula. Hardly was uttered Mr Cobden's memorable prophecy of the approach of a pacific millennium, and a universal turning of swords into spinning-jennies, when the dogs of war were let slip in every quarter of Europe. Hardly was M. Lamartine's hymn of "liberty, equality, fraternity," chanted, when the reign of internal spoliation and external violence commenced in France, and rapidly extended as far as its influence was felt throughout the world.

"And this, too, shall pass away." The reign of injustice is not eternal: it defeats itself by its own excesses: the avenging angel is found in the human heart. In the darkest days of humanity, this great law of nature is unceasingly acting, and preparing in silence the renovation of the world. It will bring about the downfall of the prætorian bands who now rule France, as it brought about the overthrow of Robespierre, the fall of Napoleon. The revolutionary tempest which is now sweeping over Europe cannot long continue. The good sense of men will reassume its sway after having violently reeled: the feelings of religion and morality will come up to the rescue of the best interests of humanity: the generous will yet combat the selfish feelings: the spirit of heaven will rise up against that of hell. It is in the eternal warfare between these opposite principles, that the true secret of the whole history of mankind is to be found: in the alternate triumph of the one and the other, that the clearest demonstration is to be discerned of the perpetual struggle between the noble and generous and selfish and corrupt desires which for ever actuate the heart of man.

"To rouse effort by the language of virtue," says Mr Alison, "and direct it to the purposes of vice, is the great art of revolution." What a commentary on these words have recent events afforded! Judging by the language of the revolutionists, they are angels descended upon earth. Nothing but gentleness, justice, philanthropy is to be seen in their expressions: nothing but liberty, equality, fraternity in their maxims. Astræa appears to have returned to the world: the lion and the kid have lain down together – Justice and Mercy have kissed each other. Judging by their actions, a more dangerous set of ruffians never obtained the direction of human affairs: justice was never more shamelessly set at nought in measures, robbery never more openly perpetrated by power. Their whole career has been one uninterrupted invasion of private rights; their whole power is founded on continual tribute to the selfish desire of individual aggrandisement among their followers. We do not ascribe this deplorable contrast between words and actions to any peculiar profligacy or want of conscience in the Provisional Government. Some of them are men of powerful intellect or fine genius; all, we believe, are sincere and well-meaning men. But "Hell is paved with good intentions." They are pushed on by a famishing crowd in their rear, whom they are alike unable to restrain or to feed. They are fanatics, and fanatics of the most dangerous kind – devout believers in human perfectibility, credulous assertors of the natural innocence of man. Thence their enormous error – thence the enormous evils they have brought upon the world – thence the incalculable importance of the great experimentum crucis as to the justice of these principles which is now taking place upon the earth.

To give one instance, among many, of the way in which these regenerators of society proceed to spoliate their neighbours, it is instructive to refer to the proposals officially promulgated by the Provisional Government, in their interview with the railway proprietors of France, whom, by one sweeping act, it was proposed to "absorb" into the state. The Minister of the Interior stated that it was proposed to "purchase" the shares of the proprietors; and the word "purchase" sounded well, and was doubtless a balm to many a quaking heart, expecting unqualified confiscation. But he soon explained what sort of "purchase" it was which was in contemplation. He said that it was the intention of Government to "absorb" all the railway shares throughout France; to take the shares at the current price in the market, and give the proprietors not money but rentes, or public securities, to the same amount! That is, having first, by means of the revolution, lowered the current value of railway stock to a twentieth, or, in some cases, a fiftieth part of what it was previous to that convulsion, they next proceed to estimate it at that depreciated value, and then pay the unhappy holders, not in cash, but in Government securities, themselves lowered to a third of their value, and perhaps ere long worth nothing. A more shameful instance of spoliation, veiled under the fine names of "absorption," centralisation, and the like, never was heard of; but the Minister of the Interior had two conclusive arguments to adduce on the subject. Some of the railway lines at least were "paying concerns," and the republic must have cash; and all of them afforded work for the labouring classes, and Government must find employment for the unemployed.

To such a length have these communist and socialist projects proceeded in Paris, that a great effort of all the holders of property was deemed indispensable to arrest them. The effort was made on Monday, 17th April; but it is hard to say whether the dreaded evils or the boasted demonstration were most perilous, or most descriptive of the present social condition of the French capital. Was it by argument in the public journals, or by influencing the electors for the approaching Assembly, or even by discussion at the Clubs, as in the days of the Jacobins and the Cordeliers, that the thing was done? Quite the reverse: it was effected by a demonstration of physical strength. They took a leaf out of the book of the Chartists – they copied the processions of the Janissaries in the Atmeidan of Constantinople. The National Guard, two hundred and twenty thousand strong, mustered on the streets of Paris: they shouted out, "A bas les Communistes!" – "A bas Blanqui!" – "Vive le Gouvernement Provisoire!" and the Parisians flattered themselves the thing was done. Is not the remedy worse than the disease? What were fifteen thousand unarmed workmen spouting socialist speeches in the Champs de Mars to 200,000 armed National Guards, dictating their commands alike to the Provisional Government and the National Assembly! Was ever a capital handed over to such a lusty band of metropolitan janissaries? What chance is there of freedom of deliberation in the future Assembly in presence of such formidable spectators in the galleries? Already M. Ledru Rollin is calculating on their ascendancy. Like all persons engaged in a successful insurrection – in other words, who have been guilty of treason – he is haunted by a continual, and in the circumstances ridiculous, dread of a counter-revolution; and in his circular of 15th April, he openly avows the principle that Paris is the soul of France; that it is the advanced guard of Freedom, not for itself alone, but the whole earth; and that the departments must not think of gainsaying the will of their sovereign leaders, or making the cause retrograde, in which all nations are finally to be blessed.

The account of this extraordinary demonstration, given in the Paris correspondence of the Times of 19th April, is so characteristic and graphic, that we cannot forbear the satisfaction of laying it before our readers. It recalls the preludes to the worst days of the first Revolution.

"Ever since the appearance of this bold defiance to the moderate majority in the Provisional Government, and its announcement that 'the gauntlet was thrown down – the death-struggle was at hand,' the city has naturally been in a state of subdued ferment. Various reports, some of the most extravagant kind, were circulated from mouth to mouth. It was said that the majority of the members of the Government intended retreating to the Tuileries, and fortifying their position – that a collision between the violent and moderate parties was imminent – that the Ultras, led by Blanqui, were to profit by a new manifestation in favour of a further delay in the general elections, and against the admission of the military into the city upon the occasion of the great fraternisation fete, in order to upset the moderate party in the Government; in fine, that Ledru Rollin, with two or three of his colleagues, was instigating, aiding, and abetting Blanqui in this movement to get rid of that majority of his other colleagues that thwarted his designs. Whatever the truth of all these rumours, the alarm was general. It soon became generally known that a monster meeting of the working classes was to be held in the Champ de Mars on the Sunday, and that Messrs Louis Blanc and Albert, instigated, it was said, by the Minister of the Interior, had convoked this assembly. The Ultra party, it was added, designed to make use of this manifestation in order to forward the schemes already mentioned. This was the state of things on Sunday morning. In the Champ de Mars, a little after noon, the scene was certainly an exciting one. Delegates of all the trades and guilds of Paris were assembled, to the number of nearly 100,000 men. Banners were waving in all directions, and the fermenting crowd filled about a third of the vast space of the plain. It was with difficulty that an explanation could be obtained of the real object of the meeting. Its ostensible object, however, appeared to be the election from among the working classes of fourteen officers for the staff of the National Guard; although other motives, such as the choice of candidates among them for the general elections, and various deputations to the Government upon various matters connected with the endless organisation of work, were also put forward. There is every reason to believe that the greater part of the meeting had in reality no other object in view, and that the other secret intrigues fomented by the Blanqui party were confined, at all events, to but a chosen few. About two o'clock the monster procession began to move towards the Hotel de Ville. Along the outer boulevards, along the esplanade of the Invalides, over the Pont de la Concorde, and along the quays, it moved on, like a huge serpent, bristling with tricoloured banners. The head of the monster appeared to have nearly reached its destination before the tail had fully left the Champ de Mars. In passing through the Faubourg St Germain, I found the rappel beating in every street; the National Guards were hurrying to their places of meeting, columns were marching forward; in every mouth was the cry that the Provisional Government was in danger from the anarchists of the Ultra party.