Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 63, No. 389, March 1848

Weary with this skirmish, and with the previous walk, Stemaw calls a halt under a big tree, and prepares to bivouac. Having started with him, we shall accompany him to the end of his expedition, the more willingly that his proceedings are very interesting, and capitally described by Mr Ballantyne, in whose words we continue to give them.

"Selecting a large pine, whose spreading branches covered a patch of ground free from underwood, he scrapes away the snow with his snow-shoe. Silently but busily he labours for a quarter of an hour; and then, having cleared a space seven or eight feet in diameter, and nearly four feet deep, he cuts down a number of small branches, which he strews at the bottom of the hollow till all the snow is covered. This done, he fells two or three of the nearest trees, cuts them up into lengths of about five feet long, and piles them at the root of the tree. A light is applied to the pile, and up glances the ruddy flame, crackling among the branches overhead, and sending thousands of bright sparks into the air. No one who has not seen it can have the least idea of the change that takes place in the appearance of the woods at night, when a large fire is suddenly lighted. Before, all was cold, silent, chilling, gloomy, and desolate, and the pale snow looked unearthly in the dark. Now, a bright ruddy glow falls upon the thick stems of the trees, and penetrates through the branches overhead, tipping those nearest the fire with a ruby tinge, the mere sight of which warms one. The white snow changes to a beautiful pink; whilst the stems of the trees, bright and clearly visible near at hand, become more and more indistinct in the distance, till they are lost in the black background. The darkness, however, need not be seen from the encampment, for, when the Indian lies down, he will be surrounded by the snowy walls, which sparkle in the firelight as if set with diamonds. These do not melt, as might be expected: the frost is much too intense for that; and nothing melts except the snow quite close to the fire. Stemaw has now concluded his arrangements: a small piece of dried deer's meat warms before the blaze, and meanwhile he spreads his green blanket on the ground, and fills a stone calumet (a pipe with a wooden stem) with tobacco, mixed with a kind of weed prepared by himself."

His pipe smoked, his venison devoured, the trapper wraps him in his blanket, and sleeps. We are then transported to a beaver-lodge at the extremity of a frozen and snow-covered lake. Yonder, where the points of a few bulrushes appear above the monotonous surface of dazzling white, are a number of small earthy mounds, the trees and bushes in whose vicinity are cut and barked in many places. It is a lively place enough in the warm season, when the beavers are busy nibbling down trees and bushes, to mend their dams and stock their storehouses with food. Now it is very different: in winter the beaver stays at home, and sleeps. His awakening is sometimes an unpleasant one.

"Do you observe that small black speck moving over the white surface of the lake, far away in the horizon? It looks like a crow, but the forward motion is much too steady and constant for that. As it approaches, it assumes the form of a man; and at last the figure of Stemaw, dragging his empty sleigh behind him, (for he has left his wolf and foxes in the last night's encampment, to be taken up when returning home,) becomes clearly distinguishable through the dreamy haze of the cold wintry morning. He arrives at the beaver-lodges, and, I warrant, will soon play havoc among the inmates.

"His first proceeding is to cut down several stakes, which he points at the ends. These are driven, after he has cut away a good deal of ice from around the beaver-lodge, into the ground between it and the shore. This is to prevent the beaver from running along the passage they always have from their lodge to the shore, where their storehouse is kept, which would make it necessary to excavate the whole passage. The beaver, if there are any, being thus imprisoned in the lodge, the hunter next stakes up the opening into the storehouse on shore, and so imprisons those that may have fled there for shelter on hearing the noise of his axe at the other house. Things being thus arranged to his entire satisfaction, he takes an instrument called an ice-chisel – which is a bit of steel about a foot long by one inch broad, fastened to the end of a stout pole, wherewith he proceeds to dig through the lodge. This is by no means an easy operation; and although he covers the snow around him with great quantities of mud and sticks, yet his work is not half finished. At last, however, the interior of the hut is laid bare, and the Indian, stooping down, gives a great pull, when out comes a large, fat, sleepy beaver, which he flings sprawling on the snow. Being thus unceremoniously awakened from its winter nap, the shivering animal looks languidly around, and even goes the length of making a face at Stemaw, by way of showing its teeth, for which it is rewarded with a blow on the head from the pole of the ice-chisel, which puts an end to it. In this way several more are killed, and packed on the sleigh. Stemaw then turns his face towards his encampment, where he collects the game left there, and away he goes at a tremendous pace, dashing the snow in clouds from his snow-shoes, as he hurries over the trackless wilderness to his forest home" – where, upon arrival, he is welcomed with immense glee by his greedy Squaw, whose lips water at the prospect of a good gorge upon fat beaver. We are not informed what sort of eating this is; but we read of soup made of beaver skins, which are oily, and stew well, resorted to by Europeans when short of provender in the dreary wilds of Hudson's Bay. Indeed all manner of queer things obtain favour as edibles in the territory of the Honourable Hudson's Bay Company. A party of Canadian voyageurs or boatmen find a basket made of bark and filled with bear's grease, which had been hidden away by Indians, who doubtless entertained the laudable design of forwarding it, per next ship, to the address of a London hairdresser. The boatmen preferred its internal application to the external one usually made of the famous capillary regenerator, and in less than two days devoured the whole of the precious ointment, spread upon the flour-cakes which, with pemican, form their usual provisions. Pemican is buffalo flesh, dried in flakes and then pounded between two stones. "These are put into a bag made of the animal's hide, with the hair on the outside, and well mixed with melted grease; the top of the bag is then sewed up, and the pemican allowed to cool. In this state it may be eaten uncooked; but the voyageurs mix it with a little flour and water, and then boil it; in which state it is known throughout the country by the elegant name of robbiboo. Pemican is good wholesome food, will keep fresh for a great length of time, and, were it not for its unprepossessing appearance, and a good many buffalo hairs mixed with it, through the carelessness of the hunters, would be very palatable." The Indians, it has already been shown, are by no means particular in their diet, and devour, with equal relish, a beaver and a kinsman. Another unusual article of food in favour amongst them is a species of white owl, which looks, we are told, when skinned, comically like very young babies. They are large and beautiful birds, sometimes nearly as big as swans. Mr Ballantyne shot one measuring five feet three inches across the wings. "They are in the habit of alighting upon the tops of blighted trees, and on poles of any kind, which happen to stand conspicuously apart from the forest trees; for the purpose, probably, of watching for birds and mice, on which they prey. Taking advantage of this habit, the Indian plants his trap (a fox trap) on the top of a bare tree, so that, when the owl alights, it is generally caught by the legs." Owls of all sizes abound in Hudson's Bay, from, the gigantic species just described, down to the small gray owl, not much bigger than a man's hand.

Hudson's Bay not being a colony, but a great waste country, sprinkled with a few European dwellings, dealings are carried on by barter rather than by cash payments, and of money there is little or none. But, to facilitate trade with the Indians, there is a certain standard of value known as a castor, and represented by pieces of wood. We may conjecture the term to have originated in the French word castor, signifying a beaver – of which animal these wooden tokens were probably intended to represent the value. It stands to reason that such a coinage is too easily counterfeited for its general circulation to be permitted, and it consequently is current only in the Company's barter-rooms. "Thus an Indian arrives at a fort with a bundle of furs, with which he proceeds to the Indian trading-room. There the trader separates the furs into different lots, and valuing each at the standard valuation, adds the amounts together, and tells the Indian, who has looked on the while with great interest and anxiety, that he has got fifty or sixty castors; at the same time handing him fifty or sixty little bits of wood in lieu of cash, so that he may, by returning these in payment of the goods for which he really exchanges his skins, know how fast his funds decrease. The Indian then looks around upon the bales of cloth, powder-horns, guns, blankets, knives, &c., with which the shop is filled, and after a good while makes up his mind to have a small blanket. This being given him, the trader tells him that the price is six castors; the purchaser hands him six of his little bits of wood, and selects something else. In this way he goes on till the wooden cash is expended. The value of a castor is from one to two shillings. The natives generally visit the establishments of the Company twice a-year; once in October, when they bring in the produce of their autumn hunts, and again in March, when they come in with that of the great winter hunt. The number of castors that an Indian makes in a winter hunt varies from fifty to two hundred, according to his perseverance and activity, and the part of the country in which he hunts. The largest amount I ever heard of was made by a man named Piaquata-Kiscum, who brought in furs, on one occasion, to the value of two hundred and sixty castors. The poor fellow was soon afterwards poisoned by his relatives, who were jealous of his superior abilities as a hunter, and envious of the favour shown him by the white men."

Mr Ballantyne visits and describes Red River settlement, the only colony in the extensive district traded over by the Hudson's Bay Company. It contained in 1843 about five thousand souls – French Canadians, Scotchmen, and Indians – and since then the population has rapidly increased. In the time of the North-West Company, since amalgamated, with that of Hudson's Bay, it was the scene of a smart skirmish or two between the rival fur-traders, in one of which Mr Semple, governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, lost his life, and a number of his men were killed and wounded. We find some curious particulars of the stratagems and manœuvres employed by the two associations to outwit each other, and get the earliest deal with the Indian hunters. But to this we can only thus cursorily refer; whilst to many other chapters of equal novelty and interest we cannot even do that. We are obliged to refuse ourselves the pleasure of a piscatorical page, in which we would have shown the brethren of the angle, roaming by loch and stream on trout and salmon intent, how in the land of Hendrik Hudson silver fish are caught whose eyes are living gold. All we can do, before laying down the pen, is to commend Mr Ballantyne's book, which does him great credit. It is unaffected and to the purpose, written in an honest, straightforward style, and is full of real interest and amusement, without the unnecessary wordiness and impertinent gossip with which books of this description are too often swollen. We are glad to learn, whilst concluding this paper, that the public will soon be enabled, by a second edition of the volume, to form a better idea of its merits than it has been possible for us to give by these few brief extracts.

THE BUDGET

The budget has just been produced, and the country has heard the lamentable exposure which the prime minister of the United Kingdom has been forced to submit to parliament. Such is the state of our financial affairs and future prospects, under the operation of the free-trade mania: and it is matter of congratulation that the mischievous and anti-national doctrines of the Manchester school should have been refuted at so early a period of their practice, and that the results of democratic rule are already made apparent even to the dullest understanding. Since warning has failed – or rather, let us say, since deep and deliberate treachery has combined with ambition and selfishness to alter the system through which Britain obtained and maintained its greatness, it is well that the hard but wholesome admonitions of experience should be felt. Better, surely, now than hereafter; before we have become familiarised to the annual tale of a declining revenue, and before we have lost heart and courage to meet the danger with a front of defiance!

The balance-sheet of last year exhibits the deplorable fact, that there is an excess of expenditure over income to the amount of very nearly Three Millions. For such a result our readers must have been perfectly prepared. We have pointed out, over and over again, the disastrous effects which were certain to follow upon the adoption of the new theories; the depreciation of property, and the depression of industry, inevitable as the consequence of such measures: and the defalcation of the revenue is the best proof of the soundness and accuracy of our views. Not that such defalcation is to be taken in any degree as the measure of our loss. It is a mere trivial fraction of the injury sustained in consequence of misguided legislation; a little proof, but a sure one, that we have entered upon the path which we must retread, unless we are to move on deliberately towards ruin. Three millions is of itself an inconsiderable sum to be provided for by the British nation, if the exigency were only temporary, and the resources of the country augmenting. But three millions may be a serious matter, if the demand is to be annual and increasing, and if, withal, our means are dwindling and notoriously on the wane.

We write at so late a period of the month, that our remarks must necessarily be contracted. Before these sheets can issue from the press, the debate will have commenced in earnest, and the proposed financial measures be thoroughly discussed in parliament. We have no wish at present to fall back upon the earlier question, or to resume consideration of the causes which have led to this extraordinary deficiency. We are content to take Lord John Russell's figures and apology as we find them. His estimates may very possibly be within the mark, and we believe he has been cautious in framing them. Warned by the experience of last year, he has not ventured to calculate upon any increase in the cardinal items of the customs and excise, thereby tacitly renouncing his faith in the realisation of the Cobdenite prophecies; and the result of the whole is, that the yearly revenue of the country, even including the present income-tax, will be, short of the expenditure by more than three millions. It may be right to subjoin Lord John Russell's own calculations.

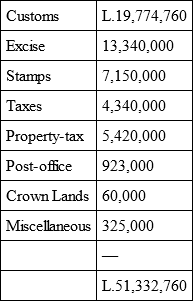

Estimated Ordinary Revenue.

Estimated Expenditure.

The calculated deficit will therefore amount to £3,263,781.

This is a lamentable enough exposition, more especially as it follows upon a year of singular hardship and depression. Burdened as we are already, both with state and with local burdens, we are now required to submit to a further pressure: the credit of the nation must be maintained, and in some way or other this additional impost must be levied. And here we shall state, at once, that, all things considered, we see no just grounds for charging Lord John Russell – or his Chancellor of the Exchequer, who seems, on this occasion, to have been superseded as incompetent – with any undue want of economy. An outcry will, of course, be made by the furious and fatuous fanatics of the League against the increase of the army and navy estimates, amounting altogether to about £300,000. This charge, for reasons which we have stated before, we believe to be just and reasonable, and it is certainly nothing more than the situation of the country demands. But supposing that not one additional shilling were to be laid out on the strengthening of either service, there would still remain a sum of nearly three millions to be provided for; and we have now to consider the means by which that additional impost may be fairly and equitably levied.

The system pursued of late years in this country, with regard to revenue matters, has been cowardly, dangerous, and, in one instance at least, deliberately deceptive. It has been cowardly, because ministers have not chosen to abide by principles which they have acknowledged to be just; but, on the contrary, for the sake of popularity and the retention of power, they have invariably yielded to clamour, and surrendered, one after another, many of the surest means of raising an adequate revenue. All idea of reducing the amount of the national debt has long since been abandoned. The moment any surplus appeared, some minor tax was remitted. If the consumer did not gain thereby, as in most instances has been the case, the ministry at least could claim credit for their desire to remove burdens; and these reductions, however profitless to the public, looked well in a financial statement. It has been dangerous, because, as a natural consequence, the remissions made in a prosperous year, when the revenue was full, caused a corresponding defalcation in another when the scales had turned against us. It is easy and popular to remove an existing tax; but difficult and decidedly obnoxious to levy a new one. We had gradually cut down our indirect taxation so far, that any further reductions became impossible, without reverting to direct taxation, which is the most grievous and oppressive, as it is usually the most unequitable method of collecting a public revenue.

We were in this position when the great financial juggle of the age was attempted; and, we are sorry to say, successfully carried through by its schemer. The history of the imposition of the income-tax in 1842, must, hereafter, to the exclusion of all minor matters, be considered the point upon which the posthumous reputation of Sir Robert Peel will rest. No minister of this country ever assumed the reins of office under auspices more favourable, if his practice had been equal to his profession. In 1841 – and the coincidence is singular – the Whigs found themselves placed in nearly the same financial difficulty as now. They had a deficit of about three millions to provide for, and they fell in consequence. All eyes were turned to Sir Robert Peel, whose prestige as a commercial minister was then at its very height. He was at the head of a great, concentrated, and enthusiastic party, whose chief fault was the consummate reliance which they were disposed to place in their leader; and the destinies of the nation were committed with extraordinary confidence into his hands. He had but to dictate his course, and every one was ready to obey. It was then that he came forward with the proposition of an income and property tax – not, be it remarked, as a permanent measure, but as the means of removing the temporary and pressing difficulty, and of sustaining the revenue until the ordinary sources should produce the necessary supply. It is needless, now, to recount the process of persuasive rhetoric employed by the minister to ensure the adoption of his scheme. The injustice of the tax was admitted; the sacrifice lauded as an example of public patriotism; and that portion of the community who were selected as the victims, so hugged, coaxed, and wheedled, that it was almost beyond the power of human nature to deny a boon which was implored in such terms of seducing endearment. And, in truth, the scheme did involve a sacrifice; because it amounted to nothing less than a partial confiscation of property. One class of the community were to be directly taxed, whilst another was allowed to go free. What was still worse, two of the united kingdoms were to be subjected to a burden from which the third was altogether relieved. On principle, the income-tax was indefensible, nor did Sir Robert Peel attempt to place his measure so high. With much seeming candour he anticipated all objections, and his scheme was carried on the faith of its merely temporary endurance.

Instead of producing three millions, as was anticipated, the income-tax returns amounted to considerably more than five; and, as trade did revive, it was within the power of Sir Robert Peel to have redeemed his pledge with honour, and to have relieved the class which had been subjected, voluntarily, to this unusual burden, at the termination of the first period of three years. It then, however, appeared that the revenue so raised had been diverted from its proper purpose. It was not used as the substitute for a temporary deficiency, but as the means of making that deficiency absolutely permanent. More indirect taxes were taken off, more duties repealed; so that, at the end of three years, it was impossible to dispense with the income-tax. In fact, the minister had broken his word. The horse, says Æsop, being desirous to avenge himself on his old enemy the stag, allowed the man to clap a saddle on his back, and to ride in pursuit. He had his revenge, indeed, but the saddle has never been removed to the present day. It would be well if, in this age, when prevarication and disingenuity are so rife in high places, the fables of the shrewd Phrygian were consulted more frequently, for the sake of the morals which they convey.

Of all the gorgeous promises held out in 1842, and since repeated, not only by ministers, but by the accredited organs of free-trade, not one has been fulfilled. Instead of the Pactolus which was to flow in to us, we find that the ordinary streams of commerce have shrunk alarmingly in their channel: instead of being relieved from the temporary income-tax, there is another deficit of three millions staring us in the face. The statutory period of the income-tax expires in April next: we are now asked to renew it for another period of five years, and to augment it, for two of these years, from three to five per cent. The income-tax, therefore, has changed its character. It is no longer a voluntary grant, but has become part and parcel of our national system of taxation. It is to be maintained and levied in order to make up for the deficiencies occasioned by the late commercial experiments; and Lord John Russell does not propose to modify or alter its arrangements in any degree whatever. It is to be drawn from the same class as before, with this difference, that whereas we have hitherto paid seven-pence in the pound, we are now to contribute a shilling.

This is, indeed, a most serious matter; and we shall look forward to the financial debate with feelings of the greatest anxiety. This is no ordinary crisis, and it must be met with corresponding fortitude and promptness. A measure, admittedly unjust in its principle, is now to be recognised as a law; and the faith which was plighted, a few years ago, to the most important section of the community, is now to be deliberately broken. Property is at last assailed, not covertly but openly; and the worst anticipations of those who deprecated our departure from the older system, are upon the eve of being realised.

Two considerations now arise, and each of them is of the utmost importance. The first concerns the policy of this measure: the second relates to its injustice. On both points we have a few words to say.

And first, as to its policy. A direct property or income-tax has hitherto been considered and acknowledged by all governments of this country as the very last which can be resorted to in cases of extraordinary emergency. In the event of danger, of war or of invasion, unusual imposts will be submitted to without a murmur: in time of peace it has always been held as a principle, that the ordinary expenditure should be met by the ordinary methods of taxation; and these have been for the most part indirect. Of all our sources of revenue, that derived from the customs, which has been most tampered with, is the easiest of collection. It amounts to much more than one-third of the whole, and in time of peace is capable of contraction and of expansion. That is the mark at which the free-traders have discharged the whole of their battery, and certainly they have succeeded in effecting a notable reduction. In consequence, we are now called upon in time of peace to submit to a war-tax, which is in effect a sort of monetary conscription. By adopting it, we sacrifice the power of falling back in any case of emergency upon a strong existing reserve. It will be conceded on all hands, that in time of war we cannot look to the customs and excise for any additional support; and if we go on multiplying direct taxation in the time of peace, to what source can we turn in the event of in unforeseen emergency? This is perhaps the most mischievous result of our adoption of the free-trade doctrines, because it leaves us utterly fettered, at the moment when freedom of action is most necessary for the safety of the whole state. We are extremely glad that on this point we are corroborated by the opinions of Mr Francis Baring, formerly Chancellor of the Exchequer under the Melbourne administration, whose clear and forcible denunciation of the proposed financial policy must have been listened to by his former colleagues with feelings of considerable shame. "At a time," said Mr Baring, "when we talk of preparing our defences, I deeply regret that we should be throwing away that which is the most powerful financial weapon in our whole armoury in the case of a war. If you now lay on a tax of five per cent, in case of a war to what source of taxation would you turn? Do you think you could raise the income-tax above five per cent? or are you prepared, at a time when you shall be in difficulty and distress, to have recourse to the taxes on customs and excise which you have so lavishly thrown away? I opposed the income-tax at its first introduction, because I thought it a dangerous course to accumulate in direct taxation any very large amount of taxation of a different kind." With these sentiments we entirely coincide; nor could such a tax, we venture to say, have been originally imposed, unless it had been broadly and explicitly stated that it was only temporary in its duration. At every step we encounter the effects of Sir Robert Peel's indefensible and cruel want of candour. Had he acted in that noble and upright spirit which has characterised British statesmen of a former age, we should have been spared that distress and difficulty; but he chose to prefer the crooked path to the straight one; he hatched and harboured commercial designs which he did not dare to impart to his colleagues, and he asked the support of a large body of the community on the strength of representations which he never intended to fulfil. It is not surprising that Lord John Russell should adopt without hesitation the legacy of his predecessor, and attempt to profit by the income-tax when he has the machinery ready to his hand. But we warn the people of this country – we warn those who were betrayed into yielding by specious promises, but who now find to their cost that they in reality are to become the bearers of the burden of the state – we warn them that the same game will be continued, and that, if they consent to this augmentation, it will not be by any means the last. If the proposals of the ministry should unfortunately be adopted, and if once more the defalcation in the national revenue should be made good – if trade again revives, and a surplus is exhibited in the balance sheet, more indirect taxes will be repealed, more tampering with our ordinary revenue be resorted to; free-trade will progress as it has begun, crippling our native industry, destroying our means, and sacrificing the British labourer even in the home market to the foreigner, until the defalcation again arises, and another attack is made directly upon property. When that time shall arrive – and unless prompt resistance is now made, we do not think it is far distant – the limits of taxation will have been reached. It will be no longer possible to go on. The lesser confiscation will give way to the greater, and the sponge be propounded as the remedy.