Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 62, Number 361, November, 1845.

"He became wild in the pursuit of pleasure; whatever changed the scene was delightful to him, and the more extravagant the better. His associates, and the frequent guests at his table, were recommended by their animal spirits and capacity as boon companions. They were stage-players and orchestral musicians, low and unprincipled persons, whose acquaintance injured him still more in reputation than in purse. Two of these men, Schickaneder, the director of a theatre (for whom Mozart wrote the 'Zauberflöte,') and Stadler, a clarionet-player, are known to have behaved with gross dishonesty towards the composer; and yet he forgave them, and continued their benefactor. The society of Schickaneder, a man of grotesque humour, often in difficulties, but of inexhaustible cheerfulness and good-fellowship, had attractions for Mozart, and led him into some excesses that contributed to the disorder of his health, as he was obliged to retrieve at night the hours lost in the day. A long-continued irregularity of income, also, disposed him to make the most of any favourable moment; and when a few rouleaus of gold brought the means of enjoyment, the Champagne and Tokay began to flow. This course is unhappily no novelty in the shifting life of genius, overworked and ill-rewarded, and seeking to throw off its cares in the pursuits and excitements of vulgar existence. It is necessary to know the composer as a man of pleasure, in order to understand certain allusions in the correspondence of his last years, when his affairs were in the most embarrassed condition, and his absence from Vienna frequently caused by the pressure of creditors. He appears at this time to have experienced moments of poignant self-reproach. His love of dancing, masquerades, masked balls, &c., was so great, that he did not willingly forego an opportunity of joining any one of those assemblies, whether public or private. He dressed handsomely, and wished to make a favourable impression in society independently of his music. He was sensitive with regard to his figure, and was annoyed when he heard that the Prussian ambassador had said to some one, 'You must not estimate the genius of Mozart by the insignificance of his exterior.' The extremity of his animal spirits may occasion surprise. He composed pantomimes and ballets, and danced in them himself, and at the carnival balls sometimes assumed a character. He was actually incomparable in Arlequin and Pierrot. The public masquerades at Vienna, during the carnival, were supported with all the vivacity of Italy; the emperor occasionally mingled in them, and his example was generally followed. We are not, therefore, to measure these enjoyments by our colder northern notions."

It should be added, what Mr Holmes tells us on good authority, that the vice of ebriety was not among Mozart's failings. "He drank to the point of exhilaration, but not beyond." His fondness for ballet-dancing may seem strange to us, who have almost a Roman repugnance to such exhibitions in men of good station. But it is possible that in some minds the love of graceful motion may be a refined passion and an exalted art; and it is singular that Mozart's wife told of him, that, in his own estimation, his taste lay in dancing rather than in music.

"That these scenes of extravagant delight seduced him into occasional indulgences, which cannot be reconciled with the purity of his earlier life, it would be the worst affectation in his biographer to deny. Nor is it necessary to the vindication of Mozart that such temporary errors should be suppressed by a feeling of mistaken delicacy. Living such a round of excitements, and tortured by perpetual misfortunes, there is nothing very surprising in the fact, that he should sometimes have been drawn into the dangerous vortex; but he redeemed the true nobility of his nature by preserving, in the midst of his hasty inconstancies, the most earnest and unfailing attachment to his home. It is a curious illustration of his real character, that he always confessed his transgressions to his wife, who had the wise generosity to pardon them, from that confidence in his truth which survived alike the troubles and temptations of their checkered lives."

Let none lightly dare either to condemn or to imitate the irregularities of life of such wondrous men as Mozart and our own Burns. Those who may be gifted with equally strong and exquisite sensibilities as they, as fine and flexible affections, as bright an imagination, beautifying every object on which its rainbow colours rest, and who have been equally tried by affliction and misconstruction, and equally tempted by brilliant opportunities of pleasure in the intervals of penury and pain – these, if they stand fast, may be allowed to speak, and they will seldom speak uncharitably, of their brethren who have fallen; or, if they fall, they may be heard to plead a somewhat similar excuse. But let ordinary men, and men less extraordinary than those we speak of, beware how they either refer to them as a reproach, or follow them as an example.

The excesses of men of genius are always exaggerated by their enemies, and often overrated even by their friends and companions. With characteristic fervour they enter enthusiastically into every thing in which they engage; and, when they indulge in dissipation, delight to sport on the brink of all its terrors, and to outvie in levity and extravagance the most practised professors of their new art. Few that see or hear them think, that even in the midst of their revels their hearts are often far away, or are extracting good from the evil spread before them; and that all the waste of time and talent, so openly and ostentatiously exhibited, is compensated in secret by longer and intenser application to the true object of their pursuit, and by acts of atonement and self-denial, of which the conscious stars of heaven are the only created witnesses. The worst operation of dissolute indulgences on genius is not, perhaps, in producing depravity of heart or habits, for its pure plumes have a virtue about them that is a preservative against pollution; but in wearing out the frame, ruffling the temper, and depressing the spirits, and thus embittering as well as shortening a career that, even when most peaceful and placid, is often destined to be short and sad enough.

The good-natured sympathy which Mozart always felt in the welfare of the very humblest of his brethren of the lyre, is highly creditable to him. But the extent to which he sacrificed his own interests to serve them, was often any thing but prudent. He was devoid of every sordid and avaricious feeling, and indeed carried his generosity to an excess.

"The extreme kindness of his nature was grossly abused by artful performers, music-sellers, and managers of theatres. Whenever any poor artists, strangers in Vienna, applied to him for assistance, he offered them the use of his house and table, introduced them to the persons whom he thought could be of use to them, and frequently composed for their use concertos, of which he did not even keep a copy, in order that they might have the exclusive advantage of playing them. But, not content with this, they sold these pieces to music-publishers; and thus repaid his kindness by robbing him. He seldom received any recompense for his pianoforte compositions, but generally wrote them for his friends, who were, of course, anxious to possess some work of his for their own use, and suited to their powers of playing. Artaria, a music-seller of Vienna, and other members of the trade, contrived to get possession of many of these pieces, and published them without obtaining the author's consent, or making him any remuneration for them. A Polish count, who was invited to a concert at Mozart's house, heard a quintet performed for the first time, with which he was so greatly delighted that he asked Mozart to compose for him a trio for the flute. Mozart agreed, on condition that he should do it at his own time. The count next day sent a polite note, expressive of his thanks for the pleasure he had enjoyed, and, along with it, one hundred gold demi-sovereigns (about £100 sterling.) Mozart immediately sent him the original score of the quintet that had pleased him so much. The count returned to Vienna a year afterwards, and, calling upon Mozart, enquired for the trio. Mozart said that he had never found himself in a disposition to write any thing worthy of his acceptance. "Perhaps, then," said the count, "you may find yourself in a disposition to return me the hundred demi-sovereigns I paid you beforehand." Mozart instantly handed him the money, but the count said not a word about the quintet; and the composer soon afterwards had the satisfaction of seeing it published by Artaria, arranged as a quartet, for the pianoforte, violin, tenor, and violoncello. Mozart's quintets for wind instruments, published also as pianoforte quartets, are among the most charming and popular of his instrumental compositions for the chamber; and this anecdote is a specimen of the manner in which he lost the benefit he ought to have derived, even from his finest works. The opera of the 'Zauberflöte' was composed for the purpose of relieving the distresses of a manager, who had been ruined by unsuccessful speculations, and came to implore his assistance. Mozart gave him the score without price, with full permission to perform it in his own theatre, and for his own benefit; only stipulating that he was not to give a copy to any one, in order that the author might afterwards be enabled to dispose of the copyright. The manager promised strict compliance with the condition. The opera was brought out, filled his theatre and his pockets, and, some short time afterwards, appeared at five or six different theatres, by means of copies received from the grateful manager."

Mozart's career, when hastening to its close, was illumined by gleams of prosperity that came but too late. On returning from Prague, in Nov. 1791, from bringing out the Clemenza di Tito, at the coronation of Leopold, the new Emperor —

"He found awaiting him the appointment of kapell-meister to the cathedral church of St Stephen, with all its emoluments, besides extensive commissions from Holland and Hungary for works to be periodically delivered. This, with his engagements for the theatres of Prague and Vienna, assured him of a competent income for the future, exempt from all necessity for degrading employment. But prospects of worldly happiness were now phantoms that only came to mock his helplessness, and embitter his parting hour."

"Now must I go," he would exclaim, "just as I should be able to live in peace; now leave my art when, no longer the slave of fashion, nor the tool of speculators, I could follow the dictates of my own feeling, and write whatever my heart prompts. I must leave my family – my poor children, at the very instant in which I should have been able to provide for their welfare."

The story of his composing the requiem for a mysterious stranger, and his melancholy forebodings during its composition, are too well known to require repetition here. The incident, to all appearance, was not extraordinary in itself, and owed its imposing character chiefly to the morbid state of Mozart's mind at the time.

On the 5th of December 1791, the ill-defined disease under which he had for some time laboured, ended in his dissolution; and subsequent examination showed that inflammation of the brain had taken place. He felt that he was dying – "The taste of death," he said to his sister-in-law, "is already on my tongue —I taste death; and who will be near to support my Constance if you go away?"

"Süssmayer (an assistant) was standing by the bedside, and on the counterpane lay the 'Requiem,' concerning which Mozart was still speaking and giving directions. As he looked over its pages for the last time, he said, with tears in his eyes, 'Did I not tell you that I was writing this for myself?'"

It should be added that this "Süssmayer, who had obtained possession of one transcript of the 'Requiem,' the other having been delivered to the stranger immediately after Mozart's decease, published the score some years afterwards, claiming to have composed from the Sanctus to the end. As there was no one to contradict this extraordinary story, it found partial credit until 1839, when a full score of the 'Requiem' in Mozart's handwriting was discovered."

We have now done. The life and character that we have been considering, speak for themselves. Mozart is not perhaps the greatest composer that ever lived, but Handel only is greater than he; and to be second to Handel, seems now to us the highest conceivable praise. Yet, in some departments, Mozart was even greater than his predecessor. It is not our intention to characterise his excellences as a composer. The millions of mankind that he has delighted in one form or other, according to their opportunities and capacities, have spoken his best panegyric in the involuntary accents of open and enthusiastic admiration; and his name will for ever be sweet in the ear of every one who has music in his soul.

Two remarks only we will make upon Mozart's taste and system as a master. The first is, that he invariably considered and proclaimed, that the great object of music was, not to astonish by its difficulty, but to delight by its beauty. Some of his own compositions are difficult as well as beautiful, and in some the beauty may be too transcendental for senses less exalted than his own. But the production of pleasure, in all its varied forms and degrees, was his uniform aim and effort; and no master has been more successful. Our next remark is, that, with all his genius, he was a laborious and learned musician; and the monument to his own fame which he has completed in his works, was built upon the most anxious, heartfelt, and humble study of all the works of excellence that then existed, and without knowing and understanding which, he truly felt that he could never have equalled or surpassed them.

TO THE EDITOR OF BLACKWOOD'S MAGAZINE

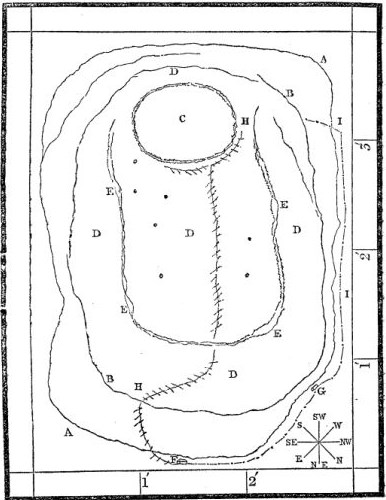

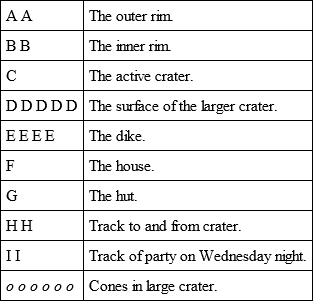

Sir, – The accompanying narrative was originally sent from the Sandwich Islands in the shape of a letter. Since my return to England, it has been suggested to me that it would suit your pages. If you think so, I shall be happy to place it at your disposal. The ground-plan annexed is intended merely to assist the description: it has no pretensions to strict accuracy, the distances have been estimated, not measured. – I remain, Sir, your obedient servant,

An Officer of the Royal Navy.ACCOUNT OF A VISIT TO THE VOLCANO OF KIRAUEA, IN OWHYHEE, SANDWICH ISLANDS, IN SEPTEMBER 1844

The ship being about to proceed to Byron's Bay, (the Hilo of the natives,) on the N.E. side of Owhyhee, to water, the captain arranged, that to give all opportunity to all those who wished to visit the volcano, distant from the anchorage forty miles, the excursion should be made in two parties. Having anchored on Wednesday the 11th of September, he and several of the officers left Hilo early on the 12th; they travelled on horseback, and returned on the ensuing Monday, highly delighted with their trip, but giving a melancholy description of the road, which they pronounced to be in some places impassable to people on foot. This latter intelligence was disheartening to the second division, some of whom, and myself of the number, had intended to walk. These, notwithstanding, adhered to their resolution; and the second party, consisting of eight, left the ship at 6 a. m. on Tuesday. Some on horseback, and some on foot, we got away from the village about eight o'clock, attended by thirteen natives, to whose calabashes our prog and clothing had been transferred; these calabashes answer this purpose admirably; they are gourds of enormous size, cut through rather above their largest diameter, which is from eighteen inches to two feet; the half of another gourd forms the lid, and keeps all clean and dry within; when filled, they are hung by net-work to each end of a pole thrown across the shoulders of a native, who will thus travel with a load of fifty or sixty pounds about three miles an hour. The day was fine and bright, and we started in high spirits, the horsemen hardly able to conceal their exultation in their superiority over the walkers, whilst they cantered over the plain from which our ascent commenced; this, 4000 feet almost gradual in forty miles, is not fatiguing; and thus, although we found the path through a wood about three miles long, very deep, and the air oppressive, we all arrived together without distress at the "half-way house," by 1 p. m. Suppose a haystack hollowed out, and some holes cut for doors and windows, and you have a picture of the "half-way house," and the ordinary dwellings of the natives of these islands; it is kept by a respectable person, chiefly for the accommodation of travellers, and in it we found the comfort of a table, a piece of furniture by these people usually considered superfluous. Here we soon made ourselves snug, commencing by throwing ourselves on the mats, and allowing a dozen vigorous urchins to "rumi rumi" us. In this process of shampooing, every muscle is kneaded or beaten; the refreshing luxury it affords can only be perfectly appreciated by those who have, like us, walked twenty miles on a bad road, in a tropical climate. Here we were to stay the night, and our first object was to prepare dinner and then to eat it; all seemed disposed to assist in the last part of this operation, and where every one was anxious to please, and determined to be pleased, sociability could not be absent. After this we whiled away our time with books and conversation, till one by one dropping asleep, all became quiet, except a wretched child belonging to our hostess, who, from one corner of the hut, every now and then set up its shrill pipe to disturb our slumbers.

Map of the Crater

Explanation of Plan: —

We were on the march the next morning at six, the walkers more confident than the horsemen, some of whose beasts did not seem at all disposed for another day's work. Our road lay for the most part through immense seas of lava, in the crevices of which a variety of ferns had taken root, and, though relieving the otherwise triste appearance, in many places shut out our view of any thing besides. Two of the walkers, and some of the horsemen, came in at the journey's end, shortly after eleven o'clock; the remainder, some leaving their horses behind them, straggled in by two p. m. Here we were at the crater! Shall I confess that my first feeling was disappointment? The plan shows some distance between the outer and inner rims, immediately below the place where the house (F) is situated; this is filled up by another level, which shuts out a great part of the prospect; the remainder was too distant, and the sun's rays too powerful, to allow of our seeing more than a quantity of smoke, and an occasional fiery ebullition from the further extremity. It was not until we had walked to the hut (G) that we became sensible of the awful grandeur of the scene below; from this point we looked perpendicularly down on the blackened mass, and felt our insignificance. The path leads between many fissures in the ground, from which sulphurous vapour and steam issue; the latter, condensing on the surrounding bushes, and falling into holes in the compact lava, affords a supply of most excellent water. As evening set in, the active volcano assumed from the house the appearance of a city in flames; long intersecting lines of fire looked like streets in a blaze; and when here and there a more conspicuous burst took place, fancy pictured a church or some large building a prey to the element. Not contented with this distant view, three of our party started for the hut, whence in the afternoon we had so fine a prospect. When there, although our curiosity was highly gratified, it prompted us to see more; so, pressing a native into our service, we proceeded along the brink of the N.W. side, until, being nearly half-way round the outer circle of the crater, we had hoped to obtain almost a bird's-eye view of the active volcano; we were therefore extremely chagrined to find, that as we drew nearer our object, it was completely shut out by a ridge below the one on which we stood. Our walking had thus far been very difficult, if not dangerous, and this, with the fatigues of the morning, had nearly exhausted our perseverance. We determined, however, to make another effort before giving it up, and were repaid by the discovery of a spur which led us down, and thence through a short valley to the point where our track (I) terminates. We came in sight of the crater as we crested the hill; the view from hence was most brilliant. The crater appeared nearly circular, and was traversed in all directions by what seemed canals of fire intensely bright; several of these radiated from a centre near the N.E. edge, so as to form a star, from which a coruscation, as if of jets of burning gas, was emitted. In other parts were furnaces in terrible activity, and undergoing continual change, sometimes becoming comparatively dark, and then bursting forth, throwing up torrents of flame and molten lava. All around the edge it seemed exceedingly agitated, and noise like surf was audible; otherwise the stillness served to heighten the effect upon the senses, which it would be difficult to describe. The waning moon warned us to return, and reluctantly we retraced our steps; it required care to do this, so that we did not get back to the house before midnight. Worn out with the day's exertions, we threw ourselves on the ground and fell asleep, but not before I had revolved the possibility of standing at the brink of the active crater after nightfall. In the morning we matured the plan, which was to descend by daylight, so as to reconnoitre our road, to return to dinner, and then, if we thought it practicable, to leave the house about 5 P.M., and to remain in the large crater till after night set in. The only objection to this scheme (and it was a most serious one) was, that when we mentioned it to the guides, they appeared completely horror-struck at the notion of it. Here, as elsewhere in the neighbourhood of volcanic activity, the common people have a superstitious dread of a presiding deity; in this place, especially, where they are scarcely rescued from heathenism, we were not surprised to find it. This, and their personal fears, (no human being ever having, as the natives assured us, entered the crater in darkness,) we then found insuperable: all we could do was to take the best guides we were able to procure with us by daylight, so that they should refresh their memories as to the locale, and ascertain if any change had taken place since their last visit, and trust to being able during our walk to persuade one to return with us in the evening. Accordingly we all left the house after breakfast, following the track marked (H), which led us precipitously down, till we landed on the surface of the large crater, an immense sheet of scoriaceous lava cooled suddenly from a state of fusion; the upheaved waves and deep hollows evidencing that congelation has taken place before the mighty agitation has subsided. It is dotted with cones 60 or 70 feet high, and extensively intersected by deep cracks, from both of which sulphurous smoke ascends. It is surrounded by a wall about twelve miles in circumference, in most parts 1000 feet deep. I despair of conveying an idea of what our sensations were, when we first launched out on this fearful pit to cross to the active crater at the further end. With all the feeling of insecurity that attends treading on unsafe ice, was combined the utter sense of helplessness the desolation of the scene encouraged: it produced a sort of instinctive dread, such as brutes might be supposed to feel in such situations. This, however, soon left us, and attending our guides, who led us away to the right for about a mile, we turned abruptly to the left, and came upon a deep dike, which, running concentric with the sides, terminates near the active crater, with which I conceive its bottom is on a level. The lava had slipped into it where we crossed, and the loose blocks were difficult to scramble over. In the lowest part where these had not fallen, the fire appeared immediately beneath the surface. The guides here evinced great caution, trying with their poles before venturing their weight; the heat was intense, and made us glad to find ourselves again on terra firma, if that expression may be allowed where the walking was exceedingly disagreeable, owing to the hollowness of the lava, formed in great bubbles, that continually broke and let us in up to our knees. This dike has probably been formed by the drainage of the volcano by a lateral vent, as the part of the crater which it confines has sunk lower than that outside it, and the contraction caused by loss of heat may well account for its width, which varies from one to three hundred yards. In support of this opinion, I may mention, that in 1840 a molten river broke out, eight miles to the eastward, and, in some places six miles broad, rolled down to the sea, where it materially altered the line of coast. From where we crossed, there is a gradual rise until within 200 yards of the volcano, when the surface dips to its margin. Owing to this we came suddenly in view of it, and, lost in amazement, walked silently on to the brink. To the party who had made the excursion the previous evening, the surprise was not so great as to the others; moreover, a bright noonday sun, and a floating mirage which made it difficult to discern the real from the deceptive, robbed the scene of much of its brilliancy; still it was truly sublime, as a feeble attempt at description will show. This immense caldron, two and three quarter miles in circumference, is filled to within twenty feet of its brim with red molten lava, over which lies a thin scum resembling the slag on a smelting furnace. The whole surface was in fearful agitation. Great rollers followed each other to the side, and, breaking, disclosed deep edges of crimson. These were the canals of fire we had noticed the night before diverging from a common centre, and the furnaces in equal activity; while what had appeared to us like jets of gas, proved to be fitful spurts of lava, thrown up from all parts of the lake (though principally from the focus near the N.E. edge) a height of thirty feet. Most people probably would have been satisfied with having witnessed this magnificent spectacle; but our admiration was so little exhausted, that the idea continually suggested itself, "How grand would this be by night!" The party who had encountered the difficulties of the walk the night before, were convinced that no greater ones existed in that of to-day; and therefore, if it continued fine, and we could induce the guide to accompany us, the project was feasible. The avarice of one of these ultimately overcame his fears, and, under his direction, we again left the house at 5 p. m., and, returning by our old track, reached the hill above the crater about the time the sun set, though long after it had sunk below the edge of the pit. Here we halted, and smoking our cigars lit from the cracks (now red-hot) which we had passed unnoticed in the glare of the sunlight, waited until it became quite dark, when we moved on; and, great as had been our expectations, we found them faint compared with the awful sublimity of the scene before us. The slag now appeared semi-transparent, and so extensively perforated as to show one sheet of liquid fire, its waves rising high, and pouring over each other in magnificent confusion, forming a succession of cascades of unequalled grandeur; the canals, now incandescent, the restless activity of the numerous vents throwing out great volumes of molten lava, the terrible agitation, and the brilliancy of the jets, which, shooting high in the air, fell with an echoless, lead-like sound, breaking the otherwise impressive stillness; formed a picture that language (at least any that I know) is quite inadequate to describe. We felt this; for no one spoke except when betrayed into an involuntary burst of amazement. On our hands and knees we crawled to the brink, and lying at full length, and shading our faces with paper, looked down at the fiery breakers as they dashed against the side of the basin beneath. The excessive heat, and the fact that the spray was frequently dashed over the edge, put a stop to this fool-hardiness; but at a more rational distance we stood gazing, with our feelings of wonder and awe so intensely excited, that we paid no regard to the entreaties of our guide to quit the spot. He at last persuaded us of the necessity of doing so, by pointing to the moon, and her distance above the dense cloud which hung, a lurid canopy, above the crater. Taking a last look, we "fell in" in Indian file, and got back to the house, with no further accident than a few bruises, about ten o'clock. The walk had required caution, and it was long after I had closed my eyes ere the retina yielded the impressions that had been so nervously drawn on them. The next morning at nine, we started on our return to the ship, sauntering leisurely along, picking strawberries by the way, and enjoying all the satisfaction inherent to the successful accomplishment of an undertaking. With health and strength for any attempt we had been peculiarly favoured by the weather, and had thus done more than any who had preceded us. Our party, under these circumstances, was most joyous; so that, independent of the object, the relaxation itself was such as we creatures of habit and discipline seldom experience.