Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 71, No. 438, April 1852

We have, of course, no reason to complain of any efforts which may be made to give the Revolutionary party a majority in the next Parliament. That is all fair and natural. It will be for the constituencies to decide whether they will return men pledged to the maintenance of the Constitution as it exists, and desirous to adopt such measures only as shall remedy injustice, and promote the harmony of interests throughout the country, or whether they will pronounce decidedly in favour of downright democracy. The question of Free Trade or Protection is undoubtedly one of immense importance, but it is not the only question which is now before the country. By bringing forward his mischievous Reform Bill, and, still more, by indicating his intention that, when brought forward again, that measure shall appear in a more extended shape, Lord John Russell has appealed, as a democrat, to the whole constituencies of Great Britain. If be returns to power, it can only be on the shoulders of the Radical party, with whose proceedings, indeed, he is now and for ever identified. The frail barrier of sentiment or opinion which separated the Ministerial Whig from the more sturdy Liberal, has been broken down by the hand of the late Premier. There is no room now for any distinction. He cannot retract what he has said, or retrieve what he has done. Of his own free will he has espoused the cause of revolution.

Therefore it is the more necessary that, at the coming election, men should distinctly understand what principle they virtually adopt in voting for particular candidates. The most strenuous efforts will be made to sink all other questions in that of the Corn Laws. We shall again hear the rhetorical commonplaces about taxing the bread of the people; and no doubt some ingenious gentlemen will illustrate their arguments, by reference to a couple of fabricated loaves of grossly unequal dimensions. For all this we are quite prepared. It has been the policy of our opponents for years back, both in their speeches and in their writings, to represent Free Trade as nothing more than the free importation of corn. In this way they get rid of the ugly circumstance, that many important branches of manufacture are still protected by large duties, and owe their present existence in this country simply to the retention of these. In this way, too, they try to persuade the other classes of the community, who are suffering under the operation of a cruel and unnational system, that they are compensated for diminished profits by the reduced price of bread, and that what they lose in wages they gain in the baker's account. A very favourite question of theirs is this – "You say that your wages are low – admitted. That is owing to the badness of the times, and circumstances over which we have no control; but we ask you to consider what your situation would be now, had the price of bread been kept up by an artificial Corn Law?" Of course, while putting such questions, they take especial care to conceal the fact, that the admitted "badness of the times" arises simply from the pernicious operation of Free Trade in another quarter; and thus they attempt to set the artisan against the agriculturist – to maintain the discord of interests, instead of promoting their harmony.

The evils which this wretched commercial system has brought both upon Great Britain and her Colonies, cannot be cured by a remedy applied solely to one injured interest. No such selfish cry has ever been raised on the part of the agriculturists; on the contrary, we have all along maintained that it is only by a deliberate revision of the whole system, with due consideration to the circumstances, of each particular interest, that the proper measure of justice to British industry can be ascertained. Lord Derby does not propose in any way to favour the agriculturist at the expense of the artisan. His object and his desire is to place British labour on its proper footing, and to secure it against being crushed by the weight of foreign competition. We are of those who firmly believe in the reciprocity of interests in this great country. We cannot understand how one large interest can be unduly prostrated for the benefit of another. We are convinced that partial legislation ever has been, and ever must be, disastrous; and we agree entirely in the sentiment expressed by an eminent orator, in a speech delivered in the House of Commons – "Let them but once diminish the consumption of British-grown corn, and from that moment the consumption of iron, of hardware, of cotton, and of woollens must decline. There would come a fresh displacement of labour, and a fresh lowering of wages; and discontent, disturbance, and misery, would prove its inevitable consequences." Now, although it may be rather out of place, in this part of our paper, to state any facts relating to the present condition of the country, we are tempted to give one instance, which fully corroborates the views of the said orator, and proves the justness of his remark. The wages of the iron miners and colliers in the west of Scotland, a numerous and important class, seeing that upwards of fifteen thousand persons are directly engaged in that branch of industry in the two counties of Lanark and Ayr, were in 1845, and previous years, from 5s. to 6s. per day – on the average five and sixpence. But now that the duty has been taken off foreign corn, and British agriculture has been depressed, their wages have fallen to 2s. 6d. or 3s. per day – on the average, two and ninepence. Now let us see what the miners have gained in exchange. The average price of wheat for the years 1842, 1843, 1844, and 1845, was 48s. 5½d. per quarter. If we assume the present price to be 38s., there is a diminution of about one-fifth. To that extent, therefore, we may presume that the miners have profited by the reduction of the price of bread; but we apprehend it would be difficult to persuade them that the benefit is at all commensurate to the loss. They may save a fifth upon one article of consumption, but their wages are reduced to one-half.

If it should be said that this is not a fair illustration, and that the depression in the iron districts arises from peculiar circumstances unconnected with the question of Free Trade, we reply, that to the iron trade, more perhaps than to any other in the kingdom, the most extravagant representations were made of the increased consumption which must follow on the opening of the ports. Not only have those promises utterly failed, but this most important branch of industry has been brought down to a point only short of absolute annihilation. The masters are not only realising no profit, but they are large annual losers by carrying on their works. The men, as we have already seen, are on half wages.

But who was the orator that, in 1839, predicted with such exceeding accuracy the decline of the iron and other trades as a necessary consequence of a diminution in the consumption of British corn? Hansard gives us the name: it is that of Sir James Graham.

In truth, unless an early and thorough revision of our whole commercial system is made, the mercantile interests of Great Britain will be placed in the greatest jeopardy. This may appear incredible to that portion of the public who are gulled by the political economists, and who are content to receive the Board of Trade returns of exports and imports as satisfactory proofs of prosperity. But there is not a merchant in one of our large towns who does not know that the case is otherwise. The present number of the Magazine contains a paper from a valued correspondent in Liverpool, giving a fearful account of the losses which have been sustained during the bygone year of prosperity and Free Trade; and we are enabled, on the very best authority, to state that Glasgow is at this moment suffering under the effects of extreme mercantile depression. This may, and undoubtedly does, conduce to cheapen commodities; but such cheapness will be dearly purchased by the sacrifice of capital, and the wholesale ruin of thousands. It is the knowledge of these facts, and, in many cases, the bitter experience of them, which has wrought such a change in the mercantile mind of the country. No one has profited – all have lost by Free Trade; and therefore it is no wonder if the resuscitated Anti-Corn-Law League should receive little countenance beyond its own particular domain. What the country most urgently requires, and what we expect to receive from the Government of Lord Derby, are measures calculated to secure the prosperity – not fictitious but real – of all the great interests of Britain; and it is to prevent the introduction of such measures that faction is exerting itself to the utmost. The Whigs cannot deny the fact that there has been a strong reaction throughout the country. They can assign that reaction to no other cause than a general conviction that the interests of the country have suffered, instead of being promoted, by the practical working of Free Trade; and the existence of that conviction is of itself a clear proof that Free Trade has not fulfilled the anticipations of those who promoted it. It has long ceased to be a theory. It has been presented in a practical shape to the people of Great Britain, who, moreover, had experience of the older system of legislation; and every individual has had the opportunity of testing its effects, and feeling its operation upon his own circumstances. Can any man believe that, if Free Trade had tended to promote the prosperity of the country, or even to maintain it in its former position, there could have been any reaction at all? In that case the opponents of Free Trade might have as well attempted to overthrow Atlas, as to assail any portion of the policy inaugurated by the late Sir Robert Peel. The educated classes of England are still what they were described by Milton – "a nation not slow nor dull, but of a quick, ingenious, and piercing spirit; acute to invent, subtile and sinewy to discourse, not beneath the reach of any point that human capacity can soar to." What effect could any arguments against Free Trade have had on their minds, if the system was daily and yearly vindicating itself by promoting the general prosperity? If the facts had been favourable to their side, our friends of the press, who, in the exuberance of their humour, were wont to accuse us of entertaining a scheme for the restoration of the Heptarchy, would have been fully justified in their banter. As it was, we managed to live on, even under the load of their ridicule, being fully convinced that the day must ere long arrive when stern experience would open the eyes of the public to the real posture of the country, in spite of every delusion which interest and ingenuity could devise.

That such delusions have been practised, and that very largely, we have had frequent occasion to show. Dull statists like Mr Porter, shallow political pretenders like Mr Cardwell, and unscrupulous compilers like the Editor of the Economist, have done their utmost to persuade the public that the proofs of national prosperity are to be found in certain tables emanating periodically from the Board of Trade. For some time we are inclined to believe that their efforts were rather successful than otherwise. Most men have an antipathy to figures, and a fondness for general results; and when they were joyously told that both the exports and the imports of the nation were on the increase, they concluded that all was right, and that the mercantile interest was advancing. We are almost inclined to give the Whig Ministry credit for the same sincere belief, at least up to the commencement of the Session of 1850. We do this the more readily, because we feel convinced that none of them were at all conversant with the real practical working of the commerce of Great Britain. If we were to make an exception at all, it would be in the case of Mr Labouchere; but this we shall not do, as ignorance is his best excuse for the statement he made regarding the position of the shipping interest in February of that year. After that period, however, it is not uncharitable to suppose that the Whigs must have lost confidence in the accuracy of their oracles. It might, undoubtedly, be too much to expect that they should have denounced oracles so perpetually delphic and comfortable to their cause, or that they should not have availed themselves of their aid in repeating to the very last the cuckoo cry of prosperity; but we must conclude that the Trade Circulars were brought, occasionally at least, under the notice of Sir Charles Wood; and surely no man, holding the office of Chancellor of Her Majesty's Exchequer, could fail to perceive that there was something manifestly inconsistent with the deductions which hitherto had been drawn from the trade tables, in the uniformly lugubrious, and frequently despairing tone of these valuable publications. The fact is that these Trade Circulars are by far the most authentic documents we have for ascertaining the real state of the country. They give us, from month to month, an accurate account of our commercial position. They emanate alike from Free-Trader and Protectionist – reveal the actual state of the market, and the amount of demand and supply – and admit of no party colouring, except as regards anticipation of the future – rather a perilous commercial vaticination, as the result of each succeeding month is expected to justify the prediction of the previous issue. For nearly three years we have been unable to glean from these circulars a word of actual comfort. They are uniform in their accounts of depression and absolute want of profit in manufactures, and all of them confess that the home trade is most miserably contracted. This being the case, of what value are the tables of export? They are valuable simply as showing that the manufacturers must export what cannot be used at home, unless they choose at once to shut up their mills, and square their accounts with the banking establishments which have given them credit – a process which, in nine cases out of ten, would lead to most unpleasant results. As to the imports upon which so much stress has been laid, let the importers of Liverpool, Glasgow, and Bristol, tell us what they have made of their speculations for the last couple of years. We sympathise, most deeply, with the valuable class of men who have so suffered. They were not the originators of the system which has proved so fearfully hostile to their interests; and we firmly believe that, in giving their support and countenance to it, they were not actuated by any selfish motive. Their mistake was this – that they believed the effect of the Free-Trade measures would be to extend the foreign market of Britain, and greatly to increase its value. They contemplated a reciprocity which has not taken place, and which never can be established, unless the governments of other states fail in their duty to their own people. And here we may remark that nothing can be more odious than the spite and rancour exhibited by the Free-Traders towards the states which have not reciprocated. If the views of some of their organs were to be carried into effect, this miserable lack of liberality would be made a casus belli, and we are not quite certain that some members of the Peace Congress would object to such a declaration. These gentlemen have no idea that any kind of manufacture, which can at all interfere with their own, ought to be permitted abroad. Since America has established her own cotton-factories, and applied herself to the working of her own mines, she has lost an amazing hold of the affections of Manchester. Sorry are we to say that Mr Cobden now seldom wafts his sighs across the Atlantic, and that apparently he has abandoned his scheme of rivetting together the valley of the Mississippi and Manchester "with hooks of steel." The smoke of an American factory is excessively nauseous to his nostrils. John Bright has ceased to take any active interest in Pennsylvania. He opines that it has denied the faith according to his principles of brotherhood; and it may be that the charge is well founded. We hope our Transatlantic friends are prepared to stand the fearful consequences. Terrible as has been the denunciation of the Manchester men, launched against Russia, Austria, and every other non-reciprocating state of Europe which has made head against British calico, the Americans must expect a fuller volley of tenfold wrath for their unprincipled tergiversation. According to the views of Manchester, a Free-trading despotism is to be preferred to a Protectionist republic. Liberty is estimated according to the return which it brings, not to the children of the soil, but to the cottonocracy of Great Britain.

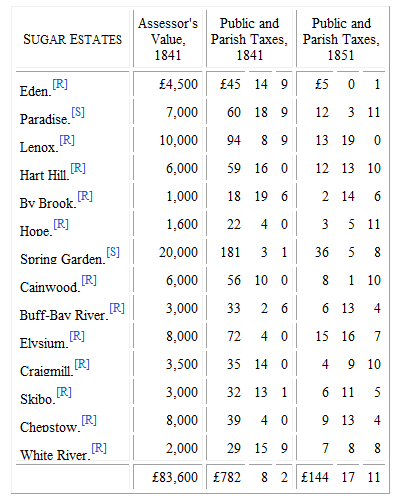

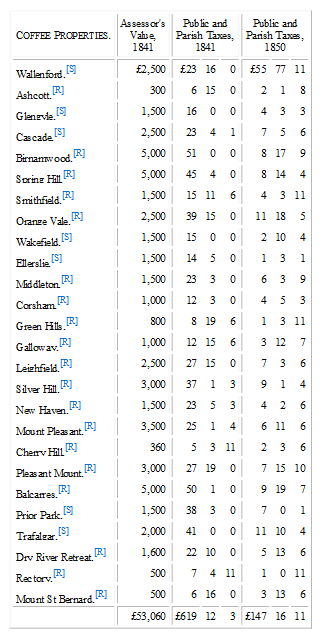

Even if it could be shown that the commercial policy at present in operation had tended to the prosperity of particular interests, and the realisation of individual fortunes, it would by no means follow, as a necessary consequence, that it is a desirable one for the nation at large. What are the symptoms which we find coincident with the increase of exports and imports? First, there is the wholesale depopulation of Ireland, and the great abandonment of tillage in that country, to the amount, we believe, of many millions of quarters of grain. Secondly, there is the ruin of the colonies, not in a metaphorical, but in the literal sense of the term. We have lying before us a copy of a Jamaica paper, The Daily Advertiser, of date 19th January last, containing a full report of a meeting in the parish of Saint George, convened for the purpose of taking into consideration the present deplorable state of the colony. We regret much that we are precluded from commenting in this article upon the statements made by the several able speakers; but we may give, as a proof of the decline of the produce of the island, the following statement by Mr Hosack: – "The past history of Jamaica shows a crop and export of 150,000 hhds. of sugar, and 34,000,000 lb. of coffee. The present shows a crop and export of 36,000 hhds. of sugar, and 5,000,000 lb. of coffee." Another gentleman, Mr Dunbar, thus described the appearance of the island: —

"The present crisis of affairs is fearfully appalling, and cannot be viewed by those immediately concerned without the greatest dismay. Within the recollection of the youngest among us, but a few years ago, our fields wore the garb of luxuriant culture; our population was active and cheerful; our homes were easy, comfortable, and hospitable; and our towns and villages presented the appearance of busy lives. Now the scene is all changed. There is a widespread desolation; the din of industry is no longer heard; we have been driven by distress from our long-cherished homes; the jungle has taken possession of the fields where, but lately, the waving canes met the eyes; our costly buildings are mouldering into decay; and we ourselves are now suspended on the brink of a precipice, created by the unwise and heartless policy of the mother country, in the lowest abyss of which we must ere long be engulfed, unless some kind protecting angel should come to the rescue."

Still more significant, perhaps, of the state of the colony is the account given by the collecting constable of the parish. We insert it here in order to show the effect of Liberal legislation upon British capital invested in a British colony: —

"I will show that properties which formerly paid £1400 taxes are now, if not entirely abandoned, very nearly so. Let the most favourable supporter of Free Trade policy ride over the Buff Bay River district, and at one glance he will see the awful, lamentable, miserably fallen state of our once valuable and flourishing coffee properties. Let him continue his ride through the sugar district, and I envy not the heart of that man who can look on approvingly when he beholds so many valuable estates grown up in common brushwood; the residences of many falling into decay, and scarce affording shelter to the watchman. Let him ask how long has all this been brought about, and I will tell him – that by the list I now hold in my hand, and about to submit to you, sir, it will be found that twenty-six of these coffee properties were valued in 1841 by the assessors of the parish, appointed by the House of Assembly, at a total of £53,060; that these properties paid £619 public and parish taxes; that fourteen of these sugar estates, now nearly all abandoned, were then valued for £83,600, and they then paid £782 taxes; that in 1850 the whole of the taxes of the twenty-six coffee properties amounted to, and were reduced to £147! – and of the fourteen sugar estates, £144. Are these not damning evidences of the destructive policy? Mr Sollas then laid before the meeting the following statement, which he had prepared for the occasion: —

[R] Abandoned.

[S] In partial cultivation.

[R] Abandoned.

[S] In partial cultivation.

– I feel, Sir, that I assert the truth when I add, that my predecessors in office collected these heavy sums within the walls of their office, and the proprietors were then in a position to pay sufficiently early, to avail themselves of the ten per cent discount allowed by law for prompt payment. How different is it with me, sir? I am necessitated not only to keep my hands constantly at the pump, but in too many cases I have been obliged to give the finishing stroke of destruction by levying upon the stock of these properties; and but for much forbearance on my part, heaven knows if others might not be hurried as quickly to ruin. These are truths patent to all; and I assert that this very fact of the taxes being so much reduced, so insignificant by comparison, and yet unable to be met, or met with the greatest difficulty, is an undeniable evidence of the total prostration of the island."

The third symptom to which we would refer is one of marked importance. We mean the enormous increase of emigrants from the British islands. The emigration from the United Kingdom, which, in 1843, amounted only to 57,212, rose in 1849 to the astounding number of 299,498, being 22,000 more than the entire combined population of the large counties of Perth and Fife, according to the census of 1841! How is that fact reconcilable with the professed prosperity of the country? Fourth, and last, because we need not here multiply examples, we have the returns of the Income-tax, which must be accepted, if anything is to be accepted, as a sure index of the state of the nation, and regarding which there can be no delusion, as in the case of export and import tables. Well, then, what do we find from these? Why, that in 1843 the amount of property assessed for trades and professions amounted to £63,021,904. That was under a protective policy. But in 1850, with Free Trade in full operation, that property, which, be it remarked, includes the entire profits arising from the commerce and manufactures of Great Britain, was estimated only at £54,977,566. Where, then, are the increased profits? Let the oracles of Free Trade explain.

Surely these are no wholesome symptoms of the state of the country. Taken singly, each of them implies an enormous amount of misery and decline; taken together, they furnish clear evidence of general national decay. They show us that trade, commerce, and manufactures are far less profitable than before. They show us that emigration from the mother country has multiplied five or six fold, and that the great stream of it is directed to America, a country which is flourishing under protective laws. They show us that agriculture, the only great staple of Irish industry, is largely on the decline. They show us that some of our once richest colonies – because the case of Jamaica is precisely that of several others – are prostrated, and the capital invested in them lost. And all this has taken place under the new commercial system!

Is this a policy to be pursued? Is it one which we are justified in pursuing? Is it one which can afford the slightest pretext for agitation? The answer to these questions must ere long be given by the country on the occasion of the general election. In the mean time, we would entreat the constituencies to consider what interests are at stake, and how much of the national welfare depends upon the nature of their decision. The symptoms of general decadence which we have just referred to cannot be gainsayed nor denied. They are clear ascertained facts, which we have, over and over again, defied the Free-Traders to account for or explain, consistently with their prosperity theories; but in no one instance yet has the challenge been accepted. We are not surprised at this backwardness. Reckless as are the champions of the League – unscrupulous as are their advocates – cunning and sophistical as are the compilers of returns – slippery as are the Whig officials – it would require more courage, craft, and ingenuity than belong to the whole body, to account satisfactorily for the one fact of the diminution of the value of the property assessed for trades and professions. While this fact remains unimpeached – and we have it on Parliamentary authority – it is absolute trash and childish babble to tell us about increased exports and imports. Here are the detailed returns. They comprise, as we have already said, the whole commercial profits of the kingdom; and if we should seem to insist, more strongly than is our wont, upon this point, our apology lies in its paramount importance.