Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 68, No 422, December 1850

The general diffusion of the means of comfort and of simple enjoyment, earned by unbought rural industry, is an idea that takes a strong hold of the imagination. The fancy wanders back to the days of the old yeomen of England, or further still to Horace's charming pictures of country life, or to Claudian's Old Man of Verona, thus rendered into glorious English by Sir John Beaumont: —

"Thrice happy he whose age is spent upon his owne,The same house sees him old that him a child hath known;He leans upon his staffe in sand where once he crept —His memory long descentes of one poor cote hath kept.Unskilful in affaires, he knows no city neare,So freely he enjoys the light of heaven more cleare.The yeeres by sev'rall corne – not consuls he computes;He notes the spring by floures, and autumne by the fruits —One space put down the sun, and bring again his rays;Thus by a certaine orbe he measures out his dayes,Rememb'ring some greate oke from small beginning spred,He sees the woode grow old which with himself was bred," &c.In every man's mind we believe there is a quiet corner, where the memories or the imaginations of country life take root and thrive spontaneously. Even the old, hardened, care-worn dweller among the sights and sins of cities will "babble o' green fields" when all other earthly things have faded from his mind. In England especially, the preference for country life amounts almost to a passion; and most of us are ready enough to admit, without demanding many reasons, that a people whose chief employment and dependence is the cultivation of their own lands, will be individually happier than if the scene of their labours were in the mine or the mill. But let us beware lest our rural partialities lead us too far.

We may acknowledge that the social condition of a country in which the land is distributed into small properties, affords, in many respects, a better chance of contentment to the people than is enjoyed by the labouring classes generally in Britain. But whether such a system be adapted to our circumstances, whether its introduction to any considerable extent be at all practicable here, is obviously quite another question. The subject has been treated hitherto by British authors with too little reference to the condition of their own country. Benevolent enthusiasts talk of peasant-proprietorship as if it were a harbour of refuge from all our difficulties, as if a return to that unsophisticated mode of life under which —ut prisca gens mortalium– each man of us should eat and be satisfied with the fruits reared by his own labour upon his own land, were at once the simplest and the most obvious remedy for our complicated social evils, and as easily accomplished as the passing of a railway suspension bill. Even Mr Laing, we think, in his former works, directed attention perhaps too exclusively to the benefits which he saw to be connected with the system in the northern parts of the Continent, without sufficiently adverting to the causes which render it unsuitable for countries situated like ours. But this omission has been remedied in the work before us, in which, after tracing the beneficial results of a minute subdivision of land property, he turns the picture, and impartially points out its unfavourable features; and to any one who has been indulging in the dream that the culture and territorial system of Belgium or Norway can be transplanted into the soil of England, we earnestly recommend the study of Mr Laing's sixth chapter. We cannot afford space to follow him through the adverse side of the argument, but may state briefly the chief points he brings forward.

In the first place, the condition of a society in which the population is principally employed in raising their food upon their own little properties, is necessarily a stationary condition. We speak, be it observed, of a people principally engaged in this occupation; for, in proportion as commerce and manufactures increase among them, labour will become expensive, capital will accumulate in masses, and the peculiar advantages of the small estate system will gradually disappear. The estates themselves will cease to be small; for, as a natural result, men who have made money will add farm to farm, and create large properties, unless there be some counteracting influence, such as the law of equal succession in France, to disperse these accumulations as fast as they arise. Two conditions, then, are necessary to the continuance of peasant-proprietorship among a people as a permanent institution. 1st, An imperfect development of trade and manufactures; and, 2d, a law of inheritance that shall discourage men from forming large properties and transmitting them to their heirs. The state of such a community then, we say, is a stationary one. Every man is like his neighbour, and each succeeding generation is only a copy of the one that preceded it – contented, it may be, industrious and peaceable, but incapable of making a single important step in civilisation. And here we see the nature and extent of that bewildering contrariety which we have noticed between man's social progress and his other interests of happiness and morality. We cannot resist the conviction that the proper destiny of man is, that in every community each generation should be wiser, as well as better and happier, than that which has gone before it. But here we have before us a condition eminently fitted to favour the latter objects, while it acts as a barrier to all material improvement in the arts, the economical applications of science, and all the refinements of social life. In his habits, tastes, and opinions, the bauer of this generation in the Rhenish provinces, the udaller of Norway, is just the same as his forefathers were five hundred years ago. His simple wants are supplied almost entirely by the industry of his own household, and the travelling pedlar furnishes him with the few articles of luxury in which he indulges. He is not only the owner, cultivator, and labourer of the land, but he is usually his own carpenter, builder, saddler, baker, brewer – often his own clothier, tailor, and shoemaker. Granting, then, that the gross produce of the soil is greater when cultivated by a race of petty landowners, than by capitalists employing hired labour, and that the land will thus maintain a greater number of agricultural labourers, it is obvious that the surplus produce that remains for the support of other branches of industry is diminished in exactly an inverse ratio. The production of commodities for exchange is therefore inconsiderable; and the growth and circulation of capital are necessarily slow.

"Petty cultivation, when pushed to its farthest extent, terminates in spade husbandry, and in it, therefore, the utmost consequences of a minute subdivision of land must be seen. There is no doubt that a country cultivated in this way could be made to produce much more than under any other system of agriculture; and were food the only necessary of man, it might therefore support a much larger population from the growth of its own soil. But then the wealth of this population would be reduced to a bare subsistence; the whole crop, or nearly all, would be consumed by those employed in raising it, and there would be little or nothing over to purchase home or foreign manufactures, the productions of art, or the works of genius, and no means of supporting a population engaged in such occupations. And even though persons might be found willing to addict themselves to the arts and sciences without expectation of pecuniary reward, yet none would be rich enough to have leisure to follow such pursuits. Thus, gradually, a universal barbarism would overspread the land."

Mr Ramsay, from whom we have copied these sentences, and whose judicious remarks on this subject well deserve the attention of the inquirer, here supposes the system of petty cultivation carried out to its utmost limits; but the same consequences, though in a less degree, will necessarily follow every step in that direction. And in point of fact, it is precisely the state of matters in those countries of Europe where agriculture is wholly carried on by peasant proprietors, – where, consequently, there is no independent and wealthy class to maintain a home trade; and the trifling commerce that exists is kept alive chiefly by the demands of that class who live on Government employment, and at the expense of the public.

We have adverted to the connection between the petty territorial system and the law of inheritance. If we could suppose the whole surface of England were to be parcelled out to-morrow into small holdings, and then placed in the hands of labouring men, it is clear that, while enterprise and the spirit of accumulation were left as free as at present, the whole arrangement would be upset before the end of the twelvemonth; and that, in a few generations at furthest, property would be found gathered into large masses, just as it is now. Some artificial means, then, would be necessary for limiting the liberty of disposing of property – some such contrivance as the compulsory law of equal succession in France and the Provinces of the Rhine – to provide against the possibility of the landowner ever becoming wealthy, and rising above the condition of a peasant. But are we prepared for all the consequences to which an equal partition of the land among the children of the peasant proprietor would inevitably lead, and has to a great extent already led in those countries? In communities such as Norway, where equal inheritance has grown up with the old institutions of the nation, and all their domestic customs are intimately connected with it, its evil effects are in a great measure neutralised by traditionary usages, which supply the place of law, and prevent the subdivision of property from reaching a dangerous extreme. But national customs cannot be adopted extempore; and the experience of France is surely a sufficient proof of the danger of attempting factitiously to adapt that system of succession to the habits and institutions of an old and highly civilised nation. And yet, without some such restriction of the freedom of testation, peasant-proprietorship, as a permanent social principle, is impossible. It is becoming every day more apparent, that the compulsory subdivision of landed property is the main source of the restless and disorganised condition of the French population. The sons of the peasant proprietor spend their youth in the labours of the farm, and look to the land alone as the means of their subsistence. The acre or two that must fall legally to their share at the death of their father is regarded as a sufficient provision against the chance of indigence; and they rarely think of seeking employment in other industrious occupations, or of applying themselves steadily to a trade. The consequence is, that at that age which, in our country, is the prime of a working man's life, they find themselves left to the bare subsistence they can scrape from their miserable inheritance – without regular occupation, unfit for mercantile pursuits, and ripe for war and social tumult. Is it possible to imagine a condition more fitted to foster that reckless and turbulent military spirit – ever ready to burst the barriers of constitutional law – which lies at the root of France's social calamities? Subdivision of land property and perpetual peace – these are the two great elements which our Manchester lawgivers think are to change the face of civilised Europe. Most truly does Mr Laing declare, that ingenuity could not have devised two principles more hostile to each other in their very nature, and more irreconcilable in the past history of the world, than those which Mr Cobden and his followers have selected as the twin pillars of their new social system.

"If Mr Cobden be right in considering this social state (the universal diffusion of property in land) pacific in its elements and tendencies, all political economy, as well as all history, must be wrong!" – (P. 110.)

No state can be pacific, no state can be secure, in which there is not an intervening class between those who govern and those who are governed – a class who shall, as our author says, act "like the buffers and ballast waggons of a railway train," and prevent those violent jerks and concussions which shake the machine of government to pieces; and the existence of such a class is excluded by the very notion of peasant proprietorship. The truth is, there are two, and only two, kinds of government compatible with the territorial system of France, and her law of succession. These are, an absolute democracy on the one hand, and military despotism on the other – the tyranny of one man or of millions; and between these two polar points of the political compass, her destinies have been vibrating for the last half century.

Let us turn our view once more homewards. We have frequently and earnestly endeavoured to impress upon the public that the accumulation of property, real as well as movable, into vast and unwieldy masses, has gone too far in our own land. We have consistently opposed that policy which tends to give capital an undue and factitious influence, and, in its precipitate zeal to stimulate production, overlooks all other interests. But we cannot deceive ourselves with the imagination, that peasant proprietorship is the specific antidote to these evils. Pleasing as such Arcadian visions may be to the speculative man, who turns away in weariness and perplexity from the struggle of discordant and competing interests, no one surely can believe that they can possibly be realised here, or that the cultivation of the land by peasant owners can ever become a normal and permanent element in our social condition. The ingenious reasonings of Mr Mill and Mr Thornton seem to establish nothing more than that such a state is compatible with good agriculture, and with that contentment which Mandeville calls "the bane of industry;" and that nations, like young couples in the honeymoon —

"Though very poor, may still be very blest."

But no one has seriously set himself to show how a system in such direct antagonism to all our existing institutions and habits – a system tantamount to a retrogression of three hundred years in our history, is to be engrafted on the laws of Great Britain. Some writers, indeed, are fond of referring obscurely to the great measures of Prince Hardenberg and Von Stein in Prussia, and to their beneficial results, as if they formed a precedent and argument for the creation of peasant estates in this country. But every one who has made himself acquainted with the true nature and purpose of the change introduced by those ministers – which was merely a commutation of certain burdens on the beneficiary owners of the land – knows that no such change is possible in Britain, simply because there are no such burdens to commute.32 An isolated experiment of such plantations may be tried here and there, and by artificial culture may be kept up for a time: but it can have no permanent influence on the nation at large. Acts of Parliament cannot make us forget what we have learnt, and relapse into the condition our fathers were in before the Revolution. We cannot retrace our steps at will, and fall back upon some imaginary stage of our past history, when contentment and rude simplicity are supposed to have overspread the land. Examples there are, no doubt, of nations once great and opulent, whose arts, inventions, and civilisation, are now almost forgotten. But changes like these are not studiously brought about by the politic enactments of rulers, but by indirect causes of decay; and a people that has once begun to go back in civilisation must gradually sink into indigence and barbarism. Whether our past advancement, then, has been for good or for evil, it is now too late to retreat. The progress of a society, composed chiefly of peasant landowners, resembles the motion of an eddy at the margin of a great stream – slowly circling for ever in the same narrow round. We, more daring than others, have ventured out into the very centre of the flood where the current rolls strongest; and to stand still now is as impossible as to breast the Spey when the winter's snows are melting on the Grampians.

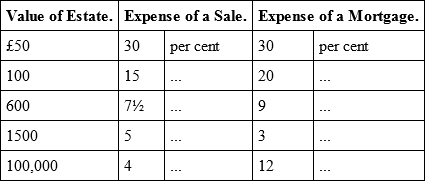

Following Mr Laing's footsteps, we have pointed out some of the dangers inseparable from a division of the soil into small estates; but we are very far indeed from considering the tenure of land in this country as incapable of amendment. It is mischievous as well as visionary to talk of remodelling our territorial system on the pattern of Prussia or Belgium, or any other country; but it is also mischievous, and most impolitic, to create or continue legal impediments to the natural subdivision of property. It is impossible to doubt that a very general desire prevails among the labouring classes, and those who have laid up little capitals in banks and friendly societies, to acquire portions of land suitable to their means of investment. The large prices paid for such lots when they are found in the market, and the eagerness with which even such dubious projects as Mr Feargus O'Connor's have been laid hold of, prove the fact to a certain extent; and it has been strongly confirmed by the inquiries of the committee which sat last session for investigating the means available to the working-classes for the investment of their small savings. The great extension of allotments, in late years, may perhaps have helped to foster this disposition; while it shows how anxious these classes are to acquire the possession of land, even on the most uncertain and unfavourable tenure. However disapprovingly our political economists may shake their heads at the progress made by that system, as not squaring with their doctrines, we cannot doubt that, so far as it has gone, its results have been eminently beneficial; and the thanks of the nation are due to that enlightened nobleman who has taken the lead in this course, and has created, we are told, no less than four thousand holdings of this description on his estates. But allotments do not meet the difficulty of finding a field for the secure investment of the smaller accumulations of industry. The question then is, whether it be right or safe that so strong and healthful a wish should prevail among the people, without the means of gratifying it? Let us shut out of view all the crude and disjointed schemes for a redistribution of property on a wider basis, and the limitation of the right of testation; and, without undermining the structure of the law, endeavour to remove those parts of it which present technical or fiscal impediments to the acquisition of small properties, and to adapt it generally to the wants of the community. The amendment of the Scotch entail law, and of the process of conveyance, as well as the recent remission of part of the burden of stamp duties, have already cleared away some of those obstacles. But much remains to be done, especially in England, in simplifying technical forms, and abridging the expense of conveyances in small transfers. In this respect, we are still far behind the nations of the Continent. Until the recent alteration of the stamp duties, the expense of effecting a sale of land in England, and of creating a mortgage, was in ordinary circumstances thus proportioned to the value of the subject: —

Who would ever dream of applying his savings in the purchase of a piece of land of £50 value, when he must pay £30 more to make a title to it? The new scale of stamp duties alters the proportion; but the expense of legal writings, which forms the larger half of the charges above stated, remains undiminished, and operates as an absolute prohibition of the sale and purchase of land for investment under £1000 value. Such are the intricacies of the system, and such the want of a proper registry,33 that we are told by the highest authorities that there is scarcely a title to be met with on which a purchaser can be quite secure, and which does not afford room for dispute and litigation. Now, contrast all this with the way in which the transfer of property is effected abroad. We have before us a copy34 of an actual conveyance of a parcel of land in the Duchy of Nassau, the price of which was £181. The form of the contract extends to only four lines, and contains a reference to an appended schedule, which specifies briefly in separate columns the description of the subject, its extent, and its number on the register. The expense of the whole transaction, including government charges, was £4, 7s. The sale of a similar estate in England would, until the other day, have been attended with an expense of about £24.

But we cannot enter into the specific means by which the exchange of land properties, especially those of small amount, may yet be facilitated; our object being merely to show how desirable, and how strictly coincident with the soundest conservative policy, it is to remove all discouragements to the natural employment of capital on the soil of the country.

This leads us to the mention of one of those topics of Mr Laing's Observations, in which his opinions seem to be more ingenious than correct; we allude to the apparently paradoxical view he takes of the ultimate consequences of abolishing agricultural protection.

Mr Laing is not an observer who runs any risk of being entangled in the obvious meshes of the Free-Trade net. He has seen too much of other countries, and has too just an appreciation of the practical value of politico-economical theories, to be deceived by the common sophisms of the Manchester dialectics. No one has more ably exposed the cardinal fallacy on which the whole system hinges – that a permanently low price of corn is necessarily beneficial to the people. In the former series of his Observations, published at a time when the common-sense of the country was beginning to give way before the bold and clamorous assertions of the League, he showed, by arguments sufficient to have convinced any one who would have listened to calm reason, that, in a country like Great Britain, the cheapness of imported corn, though it may enrich the employer of labour, cannot in the long run be an advantage to the working man. He pointed out clearly, too, the fallacy that ran through all the calculations of Dr Bowring and Mr Jacob, as to the supply of grain which the Northern countries of Europe could send us, and the price they could afford to take for it. Every week's experience is now showing the utter worthlessness of the large mass of estimates and returns compiled by these great statistical authorities, and confirming what Mr Laing foretold in opposition to all their calculations – that our principal imports would be drawn from the countries whose produce reaches us through the Baltic, at prices which, in ordinary seasons, must uniformly undersell the English grower in his own markets. The reason assigned by him is a very clear one, and well deserves the attention of those landowners and farmers at home, who are still flattering themselves with the belief that the rates and quantities of the grain imports of the last two years have been occasioned by temporary causes – that the importers must have been losing largely, and will soon cease to prosecute an unremunerative trade.

"Why cannot the British farmer, with his greater skill, capital, and economy of production, raise vastly greater crops, and undersell with advantage, at least in the British market, the foreign grain, which has heavy charges of freight, warehouse rent, and labourage against it? The reason is this: The foreign grain brought to England from the Continent or Europe consists either of rents, quit-rents, or feu-duties, paid in kind by the actual farmer; or it is the surplus produce of the small estate of the peasant proprietor. In either case the subsistence of the family producing it is taken off, and also whatever is required to pay tithe, rates, and even taxes, which, as well as rent, are not paid in money, but in naturalia– in grain, and generally in certain proportions of the crops raised. The free surplus for exportation may be sold at any price in the English market, however low; because, if it bring in nothing at all, the loss neither deranges the circumstances nor the ordinary subsistence and way of living of the farmers producing it. All their rents or payments are settled in grain; all their subsistence, clothing, and necessary expenditure are provided for; and the surplus is merely a quantity which must be sold, because it is perishable; and which, if it sells well, may enable them to lay out a little more on the gratifications and tastes of a higher state of civilisation; but if it sells badly, or for nothing at all, does not affect their means of reproduction, or even their ordinary habits, enjoyments, way of living, or stock. They have not paid a price for their corn in rent, wages, manures, and other outlay of money, as the British farmer does before he brings his corn to market, and have, therefore, no minimum below which they cannot afford to sell it without ruin."35