Полная версия

Полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 66 No.406, August 1849

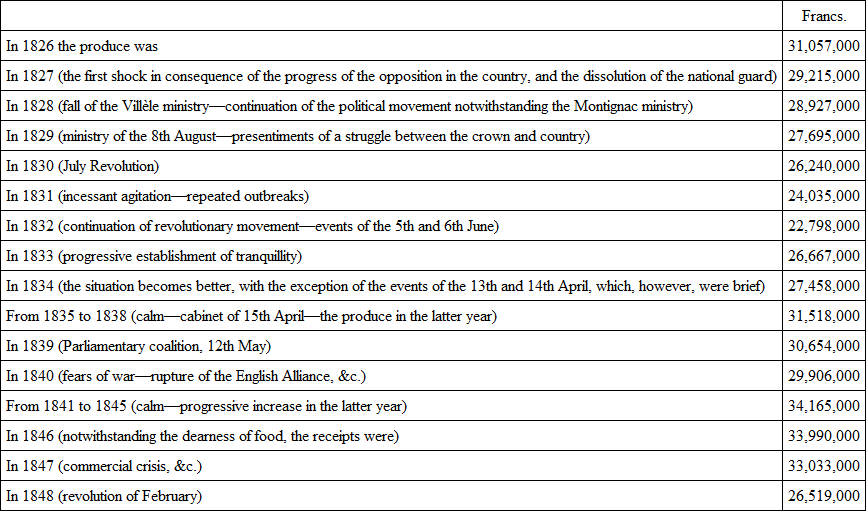

"The following from La Patrie gives a good idea of the effects of an unquiet state of society: —

"'Revolutions cost dear. They, in the first place, augment the public expenses and diminish the general resources. Occasionally they yield something, but before gathering in the profits the bill must be paid. M. Audiganne, chef de bureau at the department of commerce and agriculture, has published a curious work on the industrial crisis brought on by the revolution of February. M. Audiganne has examined all branches of manufactures, and has shown that the crisis affected every one. In the Nord, at Lisle, cotton-spinning, which occupied thirty-four considerable establishments, employing a capital of 7,000,000f. or 8,000,000f.; and tulle making, employing 195 looms, were obliged to reduce their production one-half. At Turcoing and Roubaix, where cloth and carpet manufactories occupied 12,000 workmen, the produce went down two-thirds, and 8000 men were thrown out of work. In the Pas-de-Calais the fabrication of lace and cambrics was obliged to stop before a fall of twenty-five per cent. The linen factory of Capecure, founded in 1836, and which employed 1800 men, was in vain aided by the Municipal Council of Boulogne and the local banks; it at last succumbed to the crisis. In the department of the Somme, 142,000 workmen, who were employed in the woollen, cotton, stocking, and velvet manufactories, were reduced to idleness. In the arrondissement of Abbeville, where the business, known by the name of 'lockwork' of Picardy, yielded an annual produce of 4,000,000f., the orders stopped completely, and the unfortunate workmen were obliged to go and beg their bread in the environs. At Rouen, where the cotton trade gave an annual produce of more than 250,000,000f., there were the same disasters; yet the common goods continued to find purchasers, owing to their low price. At Caen, the lace manufacture, which in 1847 employed upwards of 50,000 persons, or one-eighth of the population of Calvados, was totally paralysed. At St Quentin, tulle embroidery, which gave a living to 1500 women, received just as severe a blow as in March and April, 1848; almost all the workshops were obliged to close. In the east the loss was not less considerable. Rheims was obliged to close its woollen-thread factories during the months of March, April, and May, 1848. The communal workshop absorbed in some weeks an extraordinary loan of 430,000f. Fortunately, an order for 1,500,000f. of merinos, from New York, allowed the interrupted factories to reopen, and spared the town fresh sacrifices. The revolutionary tempest penetrated into Alsace and there swept away two-thirds of the production. Muhlhausen stopped for several months the greater number of its looms, and diminished one-half the length of labour in the workshops, which remained open. Lyons also felt all the horrors of the crisis. In the same way as muslin and lace, silk found its consumption stopped. For several months the unfortunate Lyons' workmen had for sole subsistence the produce of the colours and scarfs ordered by the Provisional Government. At St Etienne and St Chamond, the principal points of our ribbon and velvet manufacture, and where 85,000 workmen were employed, the production went down two-thirds. At Paris M. Audiganne estimates the loss in what is called Paris goods at nine-tenths of the production. The loss on other articles, he considers, on the contrary, to have been only two-thirds on the sale, and a little more than one-half on the amount of the produce. We only touch in these remarks on the most striking points of the calculation; the total loss, according to M. Audiganne, amounts, for the workmen alone, to upwards of 300,000,000f.'"

Such have been the consequences to the people of listening to the voice of their demagogues, who impelled them into the revolution of 1848 – to the national guards, of hanging back at the decisive moment, and forgetting their oaths in the intoxication of popular enthusiasm.

And if any one supposes that these effects were only temporary, and that lasting freedom is to be won for France by these sacrifices, we recommend him to consider the present state of France, a year and a half after the revolution of 1848, as painted by one of its ablest supporters, M. Louis Blanc.

"While Paris is in a state of siege, and when most of the journals which represent our opinions are by violence condemned to silence, we believe it to be a duty owing to our party to convey to it, if possible, the public expression of our sentiments.

"It is with profound astonishment that we see the organs of the counter-revolution triumph over the events of the 13th of June.

"Where there has been no contest, how can there have been a victory?

"What is then proved by the 13th of June?

"That under the pressure of 100,000 soldiers, Paris is not free in her movements? We have known this more than enough.

"Now, as it has always been, the question is, if by crowding Paris with soldiers and with cannon, by stifling with violent hands the liberty of the press, by suppressing individual freedom, by invading private domiciles, by substituting the reign of Terror for that of Reason, by unceasingly repressing furious despair – that which there is wanting a capacity to prevent, the end will be attained of reanimating confidence, or re-establishing credit, of diminishing taxes, of correcting the vices of the administration, of chasing away the spectre of the deficit, of developing industry, of cutting short the disasters attendant upon unlimited competition, of suppressing those revolts which have their source in the deep recesses of human feeling, of tranquillising resentments, of calming all hearts? The state of siege of 1848 has engendered that of 1849. The question is, if the amiable perspective of Paris in a state of siege every eight or ten months will restore to commerce its elastic movements, to the industrious their markets, and to the middle classes their repose." —L. Blanc.

It is frequently asked what is to be the end of all these changes, and under what form of government are the people of France ultimately to settle? Difficult as it is to predict anything with certainty of a people with whom nothing seems to be fixed but the disposition to change, we have no hesitation in stating our opinion that the future government of France will be what that of imperial Rome was, an Elective Military Despotism. In fact, with the exception of the fifteen years of the Restoration, when a free constitutional monarchy was imposed on its inhabitants by the bayonets of the Allies, it has ever since the Revolution of 1789 been nothing else. The Orleans dynasty has, to all appearance, expired with a disgrace even greater than that which attended its birth: the Bourbons can scarcely expect, in a country so deeply imbued with the love of change, to re-establish their hereditary throne. Popular passion and national vanity call for that favourite object in democratic societies – a rotation of governors: popular violence and general suffering will never fail to re-establish, after a brief period of anarchy, the empire of the sword. The successive election of military despots seems the only popular compromise between revolutionary passion and the social necessities of mankind; and as a similar compromise took place, after eighty years of bloodshed and confusion, in the Roman commonwealth, so, after a similar period of suffering, it will probably be repeated, from the influence of the same cause, in the French nation.

Dies Boreales

No. III.

CHRISTOPHER UNDER CANVASS.

Scene —Gutta Percha.

Time —Early Evening.

North – Buller – Seward – Talboys.

NORTH.

Trim – trim – trim —

TALBOYS.

Gentlemen, are you all seated?

NORTH.

Why into such strange vagaries fall as you would dance, Longfellow! Seize his skirts, Seward. Buller, cling to his knees. Billy, the boat-hook – he will be – he is – overboard.

TALBOYS.

Not at all. Gutta Percha is somewhat crank – and I am steadying her, sir.

NORTH.

What is that round your waist?

TALBOYS.

My Air-girdle.

NORTH.

I insist upon you dropping it, Longman. It makes you reckless. I did not think you were such a selfish character.

TALBOYS.

Alas! in this world, how are our noblest intentions misunderstood! I put it on, sir, that, in case of a capsize, I might more buoyantly bear you ashore.

NORTH.

Forgive me, my friend. But – be seated. Our craft is but indifferently well adapted for the gallopade. Be seated, I beseech you! Or, if you will stand, do plant both feet – do not – do not alternate so – and above all, do not, I implore you – show off on one, as if you were composing and reciting verses. – There, down you are – and if there be not a hole in her bottom, Gutta Percha is safe against all the hidden rocks in Loch Awe.

TALBOYS.

Let me take the stroke oar.

NORTH.

For sake of the ancient houses of the Sewards and the Bullers, sit where you are. We are already in four fathom water.

TALBOYS.

The Lines?

BILLY.

Nea, nea – Mister Talboys. Nane shall steer Perch when He's afloat but t' auld commodore.

NORTH.

Shove off, lads.

TALBOYS.

Are we on earth or in heaven?

BILLY.

On t' watter.

NORTH.

Billy – mum.

TALBOYS.

The Heavens are high – and they are deep. Fear would rise up from that Profound, if fear there could be in the perfectly Beautiful!

SEWARD.

Perhaps there is – though it wants a name.

NORTH.

We know there is no danger – and therefore we should feel no fear. But we cannot wholly disencumber ourselves of the emotions that ordinarily great depth inspires – and verily I hold with Seward, while thus we hang over the sky-abyss below with suspended oars.

SEWARD.

The Ideal rests on the Real – Imagination on Memory – and the Visionary, at its utmost, still retains relations with Truth.

BULLER.

Pray you to look at our Encampment. Nothing visionary there —

TALBOYS.

Which Encampment?

BULLER.

On the hill-side – up yonder – at Cladich.

TALBOYS.

You should have said so at first. I thought you meant that other down —

BULLER.

When I speak to you, I mean the bona fide flesh and blood Talboys, sitting by the side of the bona fide flesh and blood Christopher North, in Gutta Percha, and not that somewhat absurd, and, I trust, ideal personage, standing on his head in the water, or it may be the air, some fathoms below her keel – like a pearl-diver.

TALBOYS.

Put up your hands – so – my dear Mr North, and frame the picture.

NORTH.

And Maculloch not here! Why the hills behind Cladich, that people call tame, make a background that no art might meliorate. Cultivation climbs the green slopes, and overlays the green hill-ridges, while higher up all is rough, brown, heathery, rocky – and behind that undulating line, for the first time in my life, I see the peaks of mountains. From afar they are looking at the Tents. And far off as they are, the power of that Sycamore Grove connects them with our Encampment.

TALBOYS.

Are you sure, sir, they are not clouds?

NORTH.

If clouds, so much the better. If mountains, they deserve to be clouds; and if clouds, they deserve to be mountains.

SEWARD.

The long broad shadow of the Grove tames the white of the Tents – tones it – reduces it into harmony with the surrounding colour – into keeping with the brown huts of the villagers, clustering on bank and brae on both sides of the hollow river.

NORTH.

The cozey Inn itself from its position is picturesque.

TALBOYS.

The Swiss Giantess looks imposing —

BULLER.

So does the Van. But Deeside is the Pandemonium —

TALBOYS.

Well translated by Paterson in his Notes on Milton, "All-Devil's-Hall."

NORTH.

Hush. And how lovely the foreground! Sloping upland – with single trees standing one by one, at distances wide enough to allow to each its own little grassy domain – with its circle of bracken or broom – or its own golden gorse grove – divided by the sylvan course of the hidden river itself, visible only when it glimpses into the Loch – Here, friends, we seem to see the united occupations of pastoral, agricultural – and —

BULLER.

Pardon me, sir, I have a proposition to make.

NORTH.

You might have waited a moment till —

BULLER.

Not a moment. We all Four see the background – and the middle-ground and the foreground – and all the ground round and about – and all the islands and their shadows – and all the mountains and theirs – and, towering high above all, that Cruachan of yours, who, I firmly believe, is behind us – though 'twould twist my neck now to get a vizzy of him. No use then in describing all that lies within the visible horizon – there it is – let us enjoy it and be thankful – and let us talk this evening of whatever may happen to come into our respective heads – and I beg leave to add, sir, with all reverence, let's have fair play – let no single man – young or old – take more than his own lawful share —

NORTH.

Sir?

BULLER.

And let the subject of angling be tabooed – and all its endless botheration about baskets and rods, and reels and tackle – salmon, sea-trout, yellow-fin, perch, pike, and the Ferox – and no drivel about Deer and Eagles —

NORTH.

Sir? What's the meaning of all this – Seward, say – tell, Talboys.

BULLER.

And let each man on opening his mouth be timed– and let it be two-minute time – and let me be time-keeper – but, in consideration of your years and habits, and presidency, let time to you, sir, be extended to two minutes and thirty seconds – and let us all talk time about – and let no man seek to nullify the law by talking at railway rate – and let no man who waives his right of turn, however often, think to make up for the loss by claiming quarter of an hour afterwards – and that, too, perhaps at the smartest of the soiree – and let there be no contradiction, either round, flat, or angular – and let no man speak about what he understands – that is, has long studied and made himself master of – for that would be giving him an unfair – I had almost said – would be taking a mean advantage – and let no man —

NORTH.

Why, the mutiny at the Nore was nothing to this!

BULLER.

Lord High Admiral though you be, sir, you must obey the laws of the service —

NORTH.

I see how it is.

BULLER.

How is it?

NORTH.

But it will soon wear off – that's the saving virtue of Champagne.

BULLER.

Champagne indeed! Small Beer, smaller than the smallest size. You have not the heart, sir, to give Champagne.

NORTH.

We had better put about, gentlemen, and go ashore.

BULLER.

My ever-honoured, long-revered sir! I have got intoxicated on our Teetotal debauchery. The fumes of the water have gone to my head – and I need but a few drops of brandy to set me all right. Billy – the flask. There – I am as sober as a Judge.

NORTH.

Ay, 'tis thus, Buller, you wise wag, that you would let the "old man garrulous" into the secret of his own tendencies – too often unconscious he of the powers that have set so many asleep. I accept the law – but let it – do let it be three-minute time.

BULLER.

Five – ten – twenty – "with thee conversing I forget all time."

NORTH.

Strike medium – Ten.

BULLER.

My dear sir, for a moment let me have that Spy-glass.

NORTH.

I must lay it down – for a Bevy of Fair Women are on the Mount – and are brought so near that I hear them laughing – especially the Prima Donna, whose Glass is in dangerous proximity with my nose.

BULLER.

Fling her a kiss, sir.

NORTH.

There – and how prettily she returns it!

BULLER.

Happy old man! Go where you will —

TALBOYS.

Ulysses and the Syrens. Had he my air-girdle, he would swim ashore.

NORTH.

"Oh, mihi præteritos referat si Jupiter annos!"

TALBOYS.

The words are regretful – but there is no regret in the voice that syllables them – it is clear as a bell, and as gladsome.

NORTH.

Talking of kissing, I hear one of the most melodious songs that ever flowed from lady's lip —

"The current that with gentle motion glides,Thou knowest, being stopped, impatiently doth rage;But when his fair course is not hindered,He makes sweet music with th' enamelled stones,Giving a gentle kiss to every sedgeHe overtaketh in his pilgrimage;And so by many winding nooks he straysWith willing sport to the wild ocean."Is it not perfect?

SEWARD.

It is. Music – Painting, and Poetry —

BULLER.

Sculpture and architecture.

NORTH.

Buller, you're a blockhead. Dear Mr Alison, in his charming Essays on Taste, finds a little fault in what seems to me a great beauty in this, one of the sweetest passages in Shakspeare.

BULLER.

Sweetest. That's a miss-mollyish word.

NORTH.

Ass. One of the sweetest passages in Shakspeare. He finds fault with the Current kissing the Sedges. "The pleasing personification which we attribute to a brook is founded upon the faint belief of voluntary motion, and is immediately checked when the Poet descends to any minute or particular resemblance."

SEWARD.

Descends!

NORTH.

The word, to my ear, does sound strangely; and though his expression, "faint belief," is a true and a fine one, yet here the doctrine does not apply. Nay, here we have a true notion inconsiderately misapplied. Without doubt Poets of more wit than sensibility do follow on a similitude beyond the suggestion of the contemplated subject. But the rippling of water against a sedge suggests a kiss – is, I believe, a kiss – liquid, soft, loving, lipped.

BULLER.

Beautiful.

NORTH.

Buller, you are a fellow of fine taste. Compare the whole catalogue of metaphorical kisses – admitted and claimable – and you will find this one of the most natural of them all. Pilgrimage, in Shakspeare's day, had dropt, in the speech of our Poets, from its early religious propriety, of seeking a holy place under a vow, into a roving of the region. See his "Passionate Pilgrim." If Shakspeare found the word so far generalised, then "wanderer through the woods," or plains, or through anything else, is the suggestion of the beholding. The river is more, indeed; being, like the pilgrim, on his way to a term, and an obliged way – "the wild ocean."

SEWARD.

The "faint belief of voluntary motion" – Mr Alison's fine phrase – is one, and possibly the grounding incentive to impersonating the "current" here; but other elements enter in; liquidity – transparency – which suggest a spiritual nature, and Beauty which moves Love.

NORTH.

Ay, and the Poets of that age, in the fresher alacrity of their fancy, had a justification of comparisons, which do not occur as promptly to us, nor, when presented to us, delight so much as they would, were our fancy as alive as theirs. You might suspect a priori Ovid, Cowley, and Dryden, as likely to be led by indulgence of their ingenuity into passionless similitudes – and you may misdoubt even that Shakspeare was in danger of being so run away with. But let us have clear and unequivocal instances. This one assuredly is not of the number. It is exquisite.

TALBOYS.

Mr Alison, I presume to think, sir, should either have quoted the whole speech, or kept the whole in view, when animadverting on those two lines about the kissing Pilgrim. Julia, a Lady of Verona, beloved by Proteus, is only half-done – and now she comes – to herself.

"Then let me go, and hinder not my course;I'll be as patient as a gentle stream,And make a pastime of each weary step,Till the last step have brought me to my love;And there I'll rest, as, after much turmoil,A blessed soul doth in Elysium."The language of Shakspeare's Ladies is not the language we hear in real life. I wish it were. Real life would then be delightful indeed. Julia is privileged to be poetical far beyond the usage of the very best circles – far beyond that of any mortal creatures. For the God Shakspeare has made her and all her kin poetical – and if you object to any of the lines, you must object to them all. Eminently beautiful, sir, they are; and their beauty lies in the passionate, imaginative spirit that pervades the whole, and sustains the Similitude throughout, without a moment's flagging of the fancy, without a moment's departure from the truthfulness of the heart.

NORTH.

Talboys, I thank you – you are at the root.

SEWARD.

A wonderful thing – altogether – is Impersonation.

NORTH.

It is indeed. If we would know the magnitude of the dominion which the disposition constraining us to impersonate has exercised over the human mind, we should have to go back unto those ages of the world when it exerted itself, uncontrolled by philosophy, and in obedience to religious impulses – when Impersonations of Natural Objects and Powers, of Moral Powers and of Notions entertained by the Understanding, filled the Temples of the Nations with visible Deities, and were worshipped with altars and incense, hymns and sacrifices.

BULLER.

Was ever before such disquisition begotten by – an imaginary kiss among the Sedges!

NORTH.

Hold your tongue, Buller. But if you would see how hard this dominion is to eradicate, look to the most civilised and enlightened times, when severe Truth has to the utmost cleansed the Understanding of illusion – and observe how tenaciously these imaginary Beings, endowed with imaginary life, hold their place in our Sculpture, Painting, and Poetry, and Eloquence – nay, in our common and quiet speech.

SEWARD.

It is all full of them. The most prosaic of prosers uses poetical language without knowing it – and Poets without knowing to what extent and degree.

NORTH.

Ay, Seward, and were we to expatiate in the walks of the profounder emotions, we should sometimes be startled by the sudden apparitions of boldly impersonated Thoughts, upon occasions that did not seem to promise them – where you might have thought that interests of overwhelming moment would have effectually banished the play of imagination.

TALBOYS.

Shakspeare is justified, then – and the Lady Julia spoke like a Lady in Love with all nature – and with Proteus.

BULLER.

A most beautiful day is this indeed – but it is a Puzzler.

"The Swan on still St Mary's LakeFloats double, Swan and Shadow;"But here all the islands float double – and all the castles and abbeys – and all the hills and mountains – and all the clouds and boats and men, – double, did I say – triple – quadruple, – we are here, and there, and everywhere, and nowhere, all at the same moment. Inishail, I have you – no – Gutta Percha slides over you, and you have no material existence. Very well.

SEWARD.

Is there no house on Inishail?

NORTH.

Not one – but the house appointed for all living. A Burial-place. I see it – but not one of you – for it is little noticeable, and seldom used – on an average, one funeral in the year. Forty years ago I stepped into a small snuff-shop in the Saltmarket, Glasgow, to replenish my shell – and found my friend was from Lochawe-side. I asked him if he often revisited his native shore, and he answered – seldom, and had not for a long time – but that though his lot did not allow him to live there, he hoped to be buried in Inishail. We struck up a friendship – his snuff was good, and so was his whisky, for it was unexcised. A few years ago, trolling for Feroces, I met a boat with a coffin, and in it the body of the old tobacconist.

SEWARD.

"The Churchyard among the Mountains," in Wordsworth's Excursion, is alone sufficient for his immortality on earth.

NORTH.

It is. So for Gray's is his Elegy. But some hundred and forty lines in all – no more – yet how comprehensive – how complete! "In a Country Churchyard!" Every generation there buries the whole hamlet – which is much the same as burying the whole world – or a whole world.

SEWARD.

"The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep!"All Peasants – diers and mourners! Utmost simplicity of all belonging to life – utmost simplicity of all belonging to death. Therefore, universally affecting.