Полная версия:

The Way We Eat Now

We speak of conditions such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes as ‘non-communicable diseases’ or NCDs. You can’t catch an NCD from another person in the way that you would catch a common cold by standing next to someone who is sneezing. But what Yajnik discovered is that babies can actually ‘catch’ a predisposition towards diabetes from their mother in the womb, via the diet she eats. The babies of mothers who were undernourished during pregnancy had ‘fat-preserving tendencies’ – passed on as a survival mechanism.7

It used to be believed that India’s diabetes epidemic was mainly due to ‘thrifty’ genes, endowed over many generations on populations that suffered from patchy and inadequate food supplies. Thanks to decades of malnourishment, these populations were poorly adapted to eat a rich modern diet. Yajnik’s breakthrough was to show that the time frame of maladaptation was much shorter. He speaks not of a thrifty gene but a ‘thrifty phenotype’: the interaction of genes with the environment over a single generation. Depending on the environment in which it develops, a given gene may give rise to different phenotypes. The ‘thin-fat’ baby represents a mismatch of biological environments. These babies grew inside their malnourished mothers with phenotypes for hunger but – thanks to the huge changes in India’s food supply between the 1970s and the 1990s – found themselves eating an unexpectedly plentiful diet.8

When Yajnik first observed the ‘thin-fat’ baby in the 1990s, this was a radically new way of thinking about the interaction of nutrition and health. It took six years for Yajnik to have his first paper on the subject accepted for publication because the mainstream medical establishment was so sceptical of this idea ‘coming from an obscure Indian in an obscure place’, as he puts it. The idea of the ‘thin-fat’ baby only started to gain acceptance when Yajnik published a paper in 2004 revealing that he was a ‘thin-fat’ Indian himself.9

This 2004 paper – which he called the ‘The Y-Y paradox’ – included a now-famous photograph of Yajnik side by side with his friend and colleague John Yudkin, a British scientist: two slim middle-aged men in white shirts. The paper explained that Yajnik and Yudkin had near-identical body mass index readings of 22 kg/m2. A BMI of anything between 18.5 and 24.9 is considered healthy in the UK: not underweight and not overweight. Yajnik and Yudkin were both well within this healthy range. But X-ray imagery showed that Yajnik – the thin-fat Indian – had more than twice the body fat percentage of his friend. Yudkin’s body fat was 9.1 per cent whereas Yajnik’s, despite his slim appearance, was 21.2 per cent. Further research has confirmed that the adult Indian population in general has lower muscle mass and higher body fat than white Caucasians or African Americans.10

The story of the thin-fat babies of India is the story of the nutrition transition written on human bodies. Thanks to the new science of epigenetics, we now know that a pregnant woman’s body sends signals to her unborn child about the kind of food environment he or she will be born into. An underweight pregnant woman who eats a scarce diet is signalling to her child that food will always be scarce, which triggers a series of changes in the baby’s body, some hormonal and some physiological. For example, Yajnik found that a lack of vitamin B12 in the mother’s diet resulted in babies who were more likely to be insulin resistant.

Thin-fat babies are graphic evidence of a society in a state of dietary flux, with a shift from starvation to abundance in a generation. These Indian babies were born to mothers who lived and ate not so long ago, but the circumstances of their lives feel like another universe. There was seldom enough food, especially fats and protein, and people had to walk many miles just to get fresh water. When these women became pregnant, their babies’ bodies were metabolically programmed before birth – with their ample deposits of abdominal fat – to survive in circumstances that were harsh and lean. But the babies grew up eating in a very different and more affluent environment: a world of improved buses and electricity and labour-saving farm machinery, of cheap cooking oil and rising incomes. Millions of people in Indian cities – a new and rising middle class – have scooters where once they had only bicycles or feet. Diabetes is the worm in the apple of this new Indian prosperity.

The problems of babies born into a rapidly changing food environment are compounded by the way they are fed during the early years of life. The memory of scarcity still informs the strategies mothers use to feed babies, not just in India but everywhere in the developing world. Many of the thin-fat babies will have been fattened up in their first two years by emergency food aid. In the old India, the most urgent nutrition problem was outright hunger and overfeeding a child seemed to be the last thing anyone should worry about. This hungry India still exists to a shocking extent, with 38 per cent of all children under five so short of food that it will impair their future development, according to the Global Nutrition Report. If the alternative is to starve, rapid weight gain in the first two years of a child’s life can be a miracle. But it’s now known that this rapid growth in children who were previously malnourished may have unintended long-term consequences. Rapid growth is a risk factor for obesity and elevated blood pressure in later childhood and diabetes in adulthood. There is gathering evidence that high intake of protein and vegetable oils during the early years of feeding may result in a higher risk of obesity later in life.11

Given India’s vast population, it is perhaps not so surprising that the country currently has more patients with type 2 diabetes than any other in the world. The more startling fact is that people with diabetes form such a high percentage of that population. Already, in large cities such as Chennai, around two-thirds of the adult population is either diabetic or pre-diabetic.12

What can be done to correct the nutritional mismatch suffered by the thin-fat babies? Those working with malnourished babies in developing countries have started to talk of ‘optimal’ nutrition: the kind of childhood diet that will provide all the essential micronutrients and promote growth while minimising excess weight gain. Yajnik and his colleagues are currently working on a project giving a cohort of adolescent girls vitamin supplements which should, in theory, mean that in pregnancy their bodies will send the message to their unborn children that a world of plenty awaits them. The aim of the project is to get the bodies of the mothers to communicate more accurately with their unborn children about what food is like in modern India and thus to reduce the risk to future generations of developing NCDs. Only time will tell if these hopes come to fruition. The epigenetic messages in our bodies cannot be rewritten straight away.

Spare a thought for the grown-up thin-fat babies of the 1980s and 1990s, many of whom are now diabetics living in modern India. Through no fault of their own, these people are stuck while young with a disease they will spend a lifetime trying to manage. Living with type 2 diabetes means living on a diet that is directly at odds with the prevailing food supply. In food markets awash in lavish amounts of refined carbohydrates, they must teach themselves to be sparing with sugar and white rice. They must try to limit their calorie intake in a world that offers them ever-larger portions.

The dilemmas faced by the thin-fat Indian are an extreme version of the problems facing millions of others in the modern world. We are all affected to some degree by a series of biological clashes between the basic instincts of our bodies and the environments in which we live, and taken together, these clashes seem almost designed to make us fat. Every human baby has an inbuilt preference for sweetness, which didn’t matter too much in the days when sugar was a luxury, but which becomes a problem in a world of cheap sweeteners. We also have a natural inclination to conserve energy, which served us well as physically active hunter-gatherers and farmers but doesn’t pan out so well in cities full of cars. Many of the human instincts that evolved to help us survive have now become a liability. Yet another example is the fact that, in human biology, hunger and thirst are two separate mechanisms, which means we can drink almost any amount of sugary drinks without deriving much satisfaction from them.

The thirst conundrum

Where do you draw the line between a drink and a snack? These days, it can be hard to tell. If you eat a serving of chocolate ice cream, it counts as dessert and gives you approximately 200 calories. But if you take the same chocolate ice cream in the form of a large milkshake, the serving size may yield as much as 1,000 calories. Yet because it’s only a drink, you might have a burger and fries alongside.

It doesn’t make sense to talk about changes to eating habits without bringing in the revolution in what we drink. Perhaps no single change to our diet has contributed more to unthinking excess energy intake than liquids, both soft and alcoholic. We have reached a state where many people, adults and children, can no longer recognise a simple thirst for water, because they have become so accustomed to liquids tasting of something else.

By 2010, the average American consumed 450 calories a day from drinks, which was more than twice as many as in 1965: the equivalent of a whole meal in fluid form. Whether it’s a morning cappuccino or an evening craft beer, a green juice after a workout or an anytime bottle of Coke, the choice of calorific beverages available to us has become immense and varied. Around the world, there are bubble teas and agua frescas; cordials and energy drinks; and then there are all the new-fangled ‘craft sodas’ infused with green tea or hibiscus that pretend to be healthy, even though they probably contain nearly as much sugar as a Sprite. Many modern beverages are better thought of as food than drinks, judging by the number of calories they contain. Yet for reasons both cultural and biological, we don’t categorise most liquids as food. To our bodies, this endless stream of drinks registers as little more satisfying than water.13

Picture a typical day for an average Westerner, and start counting the drinks. It’s a lot. It surprised me to learn that more than 5 per cent of Americans now start the day with a sweetened fizzy drink, but then again, cola for breakfast is a logical enough choice if you work early shifts and don’t have access to a kitchen. A more universal morning drink is coffee, which is often more milk than coffee. Maybe there’s an orange juice on the side. (After decades of growth, however, our appetite for orange juice is finally waning, hit by growing consumer awareness that it is little more than sugar. From 2010 to 2015, the amount of Tropicana fruit juices consumed in the US dropped 12 per cent.) By mid-morning, survey data suggests that 10 per cent of Americans are ready for another coffee or soda. Personally, I am in awe of anyone who waits that long. I am so addicted to coffee, particularly when working, that I am often thinking about my second cup before I have finished the first (which is one of the reasons why I try to take my coffee black as the default. Try).14

And so our days continue, punctuated by sips of sugar-water and caffeine of one kind and another, with or without the addition of milk and various syrups, until the cocktail hour arrives, time for more soft drinks or alcohol. We sometimes imagine that the Mad Men generation of the 1950s were much bigger drinkers than the average person today. But except for a small affluent minority, Americans consumed vastly less alcohol in the 1950s than today – total alcohol intake increased fourfold from 1965 to 2002 in the US.15

This is a global story. A rise in beverage consumption is one of the key elements in the nutrition transition, wherever it has happened. In 2014, a market report on soft drinks wrote of Latin America as ‘the global bright spot for soft drinks brand owners and bottlers’.16 Young people in the emerging economies of Mexico and Argentina drink more of these drinks every year, as incomes increase. In China, people who lived their whole lives drinking nothing but unsweetened tea and water now have access to beer and fizzy drinks and a whole smorgasbord of Starbucks flavoured coffees.

It’s a sign that times are good when you can afford to quench your thirst with liquids other than water. The drinks industry – both soft and alcoholic – has conditioned us to believe that whatever the occasion, it will be improved with a drink in our hand. Studying? An energy drink will help you concentrate. Out with friends? You need a beverage to help you relax. By 2004 the average American was consuming 135 gallons of beverages a year other than water – around one and a half litres a day.17

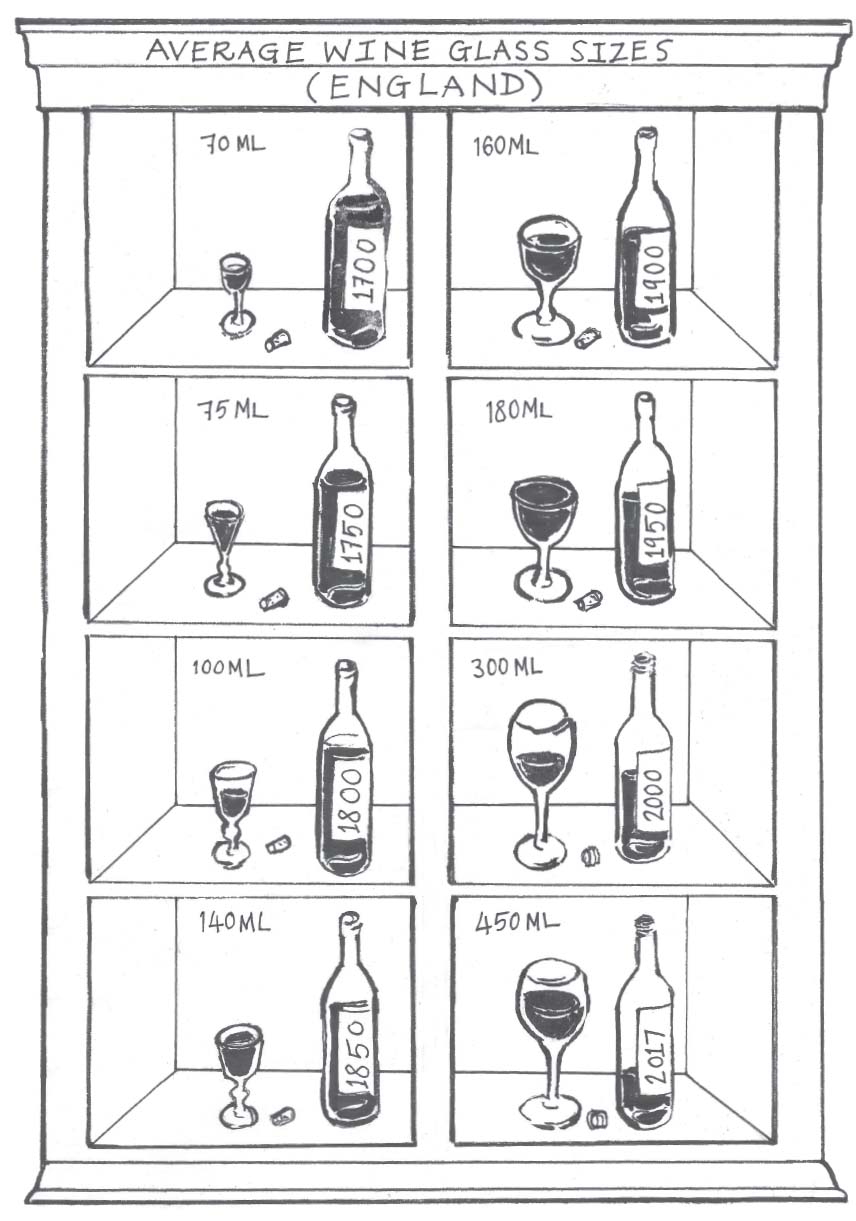

Wine glasses in England from 1700 to 2017: a sevenfold increase in size (based on an article by Theresa Marteau and colleagues in the British Medical Journal 2017).

It would be easy to paint all this modern beverage consumption as a novel kind of gluttony which those wise great-grandmothers of ours would never have indulged in. But in middle-income countries such as Mexico where much of the water supply is unsafe, buying soft drinks can be a move of self-preservation. Bottled drinks do not contain the bacteria of unclean water and are less likely to make you and your children sick. What’s more, a fizzy drink can look like the frugal choice. Given the option between paying a similar amount for a bottle of water or a bottle of cola, the cola can appear to be better value, because it offers flavouring and energy along with the liquid.

But our biology is not well adapted for this switch to high-calorie beverages. When we talk about what’s wrong with modern drinks, we discuss the problems with sugar, but we don’t talk so much about our own hunger and fullness. It seems that our genes have not evolved to be satisfied by drinking clear liquids, even when those liquids contain as much energy as a three-course lunch. This is the liquid conundrum. A person might easily drink two large glasses of Chardonnay before dinner, and then go ahead and eat a substantial meal as if nothing had happened (or maybe this is just me). Another person might have half a litre of Mountain Dew and feel no less hungry for a foot-long sandwich. With certain exceptions, our bodies simply do not register the calories from liquids in the same way that we do with solid food. This is one of the starkest mismatches between human biology and our current patterns of consumption.

Before the first experiments with honey-wines around 11,000 years ago, the only drinks available to humans were water and breast milk. For most of our evolution as a species, drinks and food were thus two entirely separate things, except for babies. There were survival benefits to keeping the mechanism of thirst separate from the mechanism of hunger. If hunter-gatherers had become full from drinking water, they wouldn’t have felt the need or desire to go out and search for food, and they would have died.18

Numerous studies have shown that most people do not compensate for the energy they drink by eating less. When you drink water, it rapidly enters your intestine, quenching your thirst but doing little to dent your hunger. The same is true even when the water is laced with sugar. It’s as if our bodies simply don’t register the calories in the same way when they arrive from a glass, a cup or a can. Clear fluids such as sports drinks, fruit juices, cola and sweetened iced teas seem to be particularly bad at killing hunger, but milk-based drinks such as lattes and chocolate milk are also surprisingly unfilling for most people, despite the nutrients they contain. Scientific studies show that people have a weak satiety response to clear drinks regardless of how many calories they are laden with – meaning that they don’t fill us up as much as the equivalent calories taken as food. And so we end up consuming a lot more energy from drinks than we intended or even knew.19

As of the year 2000, sugary drinks were the single largest source of energy in American diets. Westerners have been drinking sugar-sweetened tea and coffee for a few centuries, but never before have ‘caloric beverages’ taken up so large a proportion of the average diet. In the past, the largest source of energy in human diets would have been a staple food that actually filled a person up, such as bread. It’s a sign of how disconnected we are from our own hungers that we have reached the point when so many people receive most of their energy from something that gives our stomachs so little satisfaction.

The relationship between liquids and hunger is still not fully understood. One biological explanation for our lack of fullness after a drink is that the normal hormones – peptides – that are triggered in our gut when we eat food are not triggered when we drink sugary or alcoholic drinks. The role of these hormones is to signal to our brains that we are full. When we have a large sugary drink, there is faulty communication between our gut and our brain and somehow we don’t get the message that we have just ingested hundreds of calories.

We need a way to think about liquid-fullness as well as food-fullness. I’ve found it helpful to start telling myself that anything other than water is a snack not a drink: to be savoured, not gulped down. A cappuccino can taste amazingly creamy and delicious when you tell yourself it’s food. Whether this kind of mindful drinking would work when you have just ingested three beers and are wondering about a fourth on a Friday night is debatable, however.20

There are exceptions to the rule that liquids don’t fill us up. After all, breast milk is both food and drink to a baby. Some liquids – soup being the prime example – are actually even more filling for most people than solid food. The thickness or viscosity of a liquid seems to be important for whether it is filling or not. The more viscous a liquid is, the more it suppresses hunger.21 Our beliefs about different liquids may also affect how much satisfaction they bring us. Soup has a long-standing reputation as satisfying – something that nourishes us and feeds us, body and soul. A cold, fizzy drink, by contrast, has no such nourishing connotations.

The rise of highly marketed calorie-filled drinks is a big part of why our energy balance – calories in and calories out – is so out of sync. The average BMI of the US population has been increasing for over 250 years but it only took a sudden sharp turn upwards in the mid to late 1970s. This was the same moment when the daily energy gained from beverages suddenly increased – from 2.8 per cent of all energy to 7 per cent for the average person. Correlation is not causation, but the timing supports an association between rising beverage intake and rising obesity. The correlation between a sudden growth in consumption of caloric drinks and increasing BMI maps onto the whole population, across all ages and ethnic groups.22

Mainstream opinion will – charmingly – tell a person that if he or she is fat, the reason must be a lack of willpower. But the example of calorie-laden drinks shows once again that obesity cannot simply be attributed to individual laziness or greed. Around forty years ago, companies began marketing a completely new set of drinks to American and European consumers. Another couple of decades on and these novel liquids were travelling the world and becoming ever larger. In 2015, Starbucks marketed a cinnamon-roll-flavoured frappuccino that contained twenty teaspoons of sugar (102 grams) in a single serving. In some ways, the surprise is not that two-thirds of the population in the UK and US are overweight or obese; but that one-third of the population are not.23

Yet we live in a culture that says that despite all this sugar being pumped into our drinks, we are not allowed to be fat. This is one of the cruellest aspects of our current food culture. There is a huge mismatch between the availability of foods and drinks and the way we talk about the people who consume the most everyday and easily available items.

The stigmatised majority

In most countries, the majority of people eating today are overweight or obese. Yet there has been remarkably little discussion of how the overall experience of eating is affected by this change. We wring our hands about the ‘obesity crisis’ but we do not pay much attention to how it feels to eat in the modern world as a person with obesity. Culturally, we have not yet adapted to the new reality and we continue to hold up slim bodies as ‘normal’. This is sad, not least because the psychology of fat shaming is one of the reasons most people with obesity find it so hard to lose weight.

The fact that weight stigma is a problem has been known since the 1960s. A series of studies carried out by sociologists in the early 1960s found that when shown pictures of six children and asked to rank them in order of preference, ten-year-old American girls consistently ranked the girl with obesity as the least preferred, lower in the friendship stakes than a child in a wheelchair, a child with facial disfigurement or a child with an amputated arm.24

In 1968, a German-American sociologist called Werner Cahnman published an article titled ‘The Stigma of Obesity’. In it, Cahnman documented the terrible discrimination suffered by young people with obesity in America, based on a series of thirty-one interviews he conducted at an obesity clinic in New York City. They told him stories of rejection and ridicule, of doors slammed and opportunities lost. Rejection of people with obesity ‘is built into our culture’, wrote Cahnman. In 1938, as a young Jewish man, Cahnman had been interred in the Dachau concentration camp. After his escape, he emigrated to the US, where he spent much of his career as a sociologist considering the various forms that social prejudices took. To him, it was clear that being overweight in America was not just seen as ‘detrimental to health’ but as ‘morally reprehensible’.25

The worst aspect of weight stigma, Cahnman suggested, was that it created an internalised sense of shame from which the obese ‘cannot free themselves’. In the fifty years since Cahnman’s article was published, much research has been done confirming that weight stigma has damaging effects on the health and wellbeing of the stigmatised.

Yet stigma about being overweight or obese goes almost unchallenged. Negative messaging about fatness is the norm rather than the exception in our culture and has become a global phenomenon. There used to be numerous cultures where non-thin bodies were celebrated, but a study from 2011 found that fat stigma has now spread to Mexico, Paraguay and American Samoa. Meanwhile in Western societies, psychologist A. Janet Tomiyama has found, weight stigma is now ‘more socially acceptable, severe, and in some cases more prevalent than racism, sexism and other forms of bias’.26

Clearly, not everyone who is overweight or obese is equally sensitised to negative stereotypes about weight. Some are cheerfully unfussed by such questions as body mass index, while others find solace and pride in the ‘body acceptance’ movement that celebrates human bodies in all their diversity. Nevertheless, the indications are that millions of people worldwide are negatively affected – both psychologically and physically – by obesity stigma.

The history of public health is littered with examples of health-related stigma, and it never ends well for those affected. Cholera, syphilis and tuberculosis were all impossible to bring under control when the sufferers were seen as morally to blame. In 2017, an editorial in the British medical journal The Lancet argued that health systems will never effectively prevent childhood obesity until it stops being treated as a personal moral failing caused by faulty willpower. Until there is collective recognition that obesity is ‘not a lifestyle choice’, argues The Lancet, the prevalence of obesity is unlikely to be reduced.27