Полная версия

Полная версияDaddy Long-Legs

I really believe I ’ve finished, Daddy. Nothing else occurs to me at the moment—I ’ll try to write a longer letter next time.

Yours always,Judy.P. S. The lettuce has n’t done at all well this year. It was so dry early in the season.

August 25th.

Well, Daddy, Master Jervie’s here. And such a nice time as we ’re having! At least I am, and I think he is, too—he has been here ten days and he does n’t show any signs of going. The way Mrs. Semple pampers that man is scandalous. If she indulged him as much when he was a baby, I don’t know how he ever turned out so well.

He and I eat at a little table set on the side porch, or sometimes under the trees, or—when it rains or is cold—in the best parlor. He just picks out the spot he wants to eat in and Carrie trots after him with the table. Then if it has been an awful nuisance, and she has had to carry the dishes very far, she finds a dollar under the sugar bowl.

He is an awfully companionable sort of man, though you would never believe it to see him casually; he looks at first glance like a true Pendleton, but he is n’t in the least. He is just as simple and unaffected and sweet as he can be—that seems a funny way to describe a man, but it ’s true. He ’s extremely nice with the farmers around here; he meets them in a sort of man-to-man fashion that disarms them immediately. They were very suspicious at first. They did n’t care for his clothes! And I will say that his clothes are rather amazing. He wears knickerbockers and pleated jackets and white flannels and riding clothes with puffed trousers. Whenever he comes down in anything new, Mrs. Semple, beaming with pride, walks around and views him from every angle, and urges him to be careful where he sits down; she is so afraid he will pick up some dust. It bores him dreadfully. He ’s always saying to her:

“Run along, Lizzie, and tend to your work. You can’t boss me any longer. I ’ve grown up.”

It ’s awfully funny to think of that great, big, long-legged man (he ’s nearly as long-legged as you, Daddy) ever sitting in Mrs. Semple’s lap and having his face washed. Particularly funny when you see her lap! She has two laps now, and three chins. But he says that once she was thin and wiry and spry and could run faster than he.

Such a lot of adventures we ’re having! We ’ve explored the country for miles, and I ’ve learned to fish with funny little flies made of feathers. Also to shoot with a rifle and a revolver. Also to ride horse-back—there ’s an astonishing amount of life in old Grove. We fed him on oats for three days, and he shied at a calf and almost ran away with me.

We climbed Sky Hill Monday afternoon. That ’s a mountain near here; not an awfully high mountain, perhaps—no snow on the summit—but at least you are pretty breathless when you reach the top. The lower slopes are covered with woods, but the top is just piled rocks and open moor. We stayed up for the sunset and built a fire and cooked our supper. Master Jervie did the cooking; he said he knew how better than me—and he did, too, because he ’s used to camping. Then we came down by moonlight, and, when we reached the wood trail where it was dark, by the light of an electric bulb that he had in his pocket. It was such fun! He laughed and joked all the way and talked about interesting things. He ’s read all the books I ’ve ever read, and a lot of others besides. It ’s astonishing how many different things he knows.

We went for a long tramp this morning and got caught in a storm. Our clothes were drenched before we reached home—but our spirits not even damp. You should have seen Mrs. Semple’s face when we dripped into her kitchen.

“Oh, Master Jervie—Miss Judy! You are soaked through. Dear! Dear! What shall I do? That nice new coat is perfectly ruined.”

She was awfully funny; you would have thought that we were ten years old, and she a distracted mother. I was afraid for a while that we were n’t going to get any jam for tea.

Saturday.

I started this letter ages ago, but I have n’t had a second to finish it.

Is n’t this a nice thought from Stevenson?

The world is so full of a number of things,I am sure we should all be as happy as kings.It ’s true, you know. The world is full of happiness, and plenty to go round, if you are only willing to take the kind that comes your way. The whole secret is in being pliable. In the country, especially, there are such a lot of entertaining things. I can walk over everybody’s land, and look at everybody’s view, and dabble in everybody’s brook; and enjoy it just as much as though I owned the land—and with no taxes to pay!

…It ’s Sunday night now, about eleven o’clock, and I am supposed to be getting some beauty sleep, but I had black coffee for dinner, so—no beauty sleep for me!

This morning, said Mrs. Semple to Mr. Pendleton, with a very determined accent:

“We have to leave here at a quarter past ten in order to get to church by eleven.”

“Very well, Lizzie,” said Master Jervie, “you have the surrey ready, and if I ’m not dressed, just go on without waiting.”

“We ’ll wait,” said she.

“As you please,” said he, “only don’t keep the horses standing too long.”

Then while she was dressing, he told Carrie to pack up a lunch, and he told me to scramble into my walking clothes; and we slipped out the back way and went fishing.

It discommoded the household dreadfully, because Lock Willow of a Sunday dines at two. But he ordered dinner at seven—he orders meals whenever he chooses; you would think the place were a restaurant—and that kept Carrie and Amasai from going driving. But he said it was all the better because it was n’t proper for them to go driving without a chaperon; and anyway, he wanted the horses himself to take me driving. Did you ever hear anything so funny?

And poor Mrs. Semple believes that people who go fishing on Sundays, go afterwards to a sizzling hot hell! She is awfully troubled to think that she did n’t train him better when he was small and helpless and she had the chance. Besides—she wished to show him off in church.

Anyway, we had our fishing (he caught four little ones) and we cooked them on a camp-fire for lunch. They kept falling off our spiked sticks into the fire, so they tasted a little ashy, but we ate them. We got home at four and went driving at five and had dinner at seven, and at ten I was sent to bed—and here I am, writing to you.

I am getting a little sleepy though.

Good night.Here is a picture of the one fish I caught.

Ship ahoy, Cap’n Long-Legs!

Avast! Belay! Yo, ho, ho, and a bottle of rum. Guess what I ’m reading? Our conversation these past two days has been nautical and piratical. Is n’t “Treasure Island” fun? Did you ever read it, or was n’t it written when you were a boy? Stevenson only got thirty pounds for the serial rights—I don’t believe it pays to be a great author. Maybe I ’ll teach school.

Excuse me for filling my letters so full of Stevenson; my mind is very much engaged with him at present. He comprises Lock Willow’s library.

I ’ve been writing this letter for two weeks, and I think it ’s about long enough. Never say, Daddy, that I don’t give details. I wish you were here, too; we ’d all have such a jolly time together. I like my different friends to know each other. I wanted to ask Mr. Pendleton if he knew you in New York—I should think he might; you must move in about the same exalted social circles, and you are both interested in reforms and things—but I could n’t, for I don’t know your real name.

It ’s the silliest thing I ever heard of, not to know your name. Mrs. Lippett warned me that you were eccentric. I should think so!

Affectionately,Judy.P. S. On reading this over, I find that it is n’t all Stevenson. There are one or two glancing references to Master Jervie.

September 10th.

Dear Daddy,

He has gone, and we are missing him! When you get accustomed to people or places or ways of living, and then have them suddenly snatched away, it does leave an awfully empty, gnawing sort of sensation. I ’m finding Mrs. Semple’s conversation pretty unseasoned food.

College opens in two weeks and I shall be glad to begin work again. I have worked quite a lot this summer though—six short stories and seven poems. Those I sent to the magazines all came back with the most courteous promptitude. But I don’t mind. It ’s good practice. Master Jervie read them—he brought in the mail, so I could n’t help his knowing—and he said they were dreadful. They showed that I did n’t have the slightest idea of what I was talking about. (Master Jervie does n’t let politeness interfere with truth.) But the last one I did—just a little sketch laid in college—he said was n’t bad; and he had it typewritten, and I sent it to a magazine. They ’ve had it two weeks; maybe they ’re thinking it over.

You should see the sky! There ’s the queerest orange-colored light over everything. We ’re going to have a storm.

…It commenced just that moment with drops as big as quarters and all the shutters banging. I had to run to close windows, while Carrie flew to the attic with an armful of milk pans to put under the places where the roof leaks—and then, just as I was resuming my pen, I remembered that I ’d left a cushion and rug and hat and Matthew Arnold’s poems under a tree in the orchard, so I dashed out to get them, all quite soaked. The red cover of the poems had run into the inside; “Dover Beach” in the future will be washed by pink waves.

A storm is awfully disturbing in the country. You are always having to think of so many things that are out of doors and getting spoiled.

Thursday.

Daddy! Daddy! What do you think? The postman has just come with two letters.

1st.—My story is accepted. $50.

Alors! I ’m an AUTHOR.

2d.—A letter from the college secretary. I ’m to have a scholarship for two years that will cover board and tuition. It was founded by an alumna for “marked proficiency in English with general excellency in other lines.” And I ’ve won it! I applied for it before I left, but I did n’t have an idea I ’d get it, on account of my Freshman bad work in math. and Latin. But it seems I ’ve made it up. I am awfully glad, Daddy, because now I won’t be such a burden to you. The monthly allowance will be all I ’ll need, and maybe I can earn that with writing or tutoring or something.

I ’m crazy to go back and begin work.

Yours ever,Jerusha Abbott,Author of, “When the Sophomores Won the Game.” For sale at all news stands, price ten cents.September 26th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

Back at college again and an upper classman. Our study is better than ever this year—faces the South with two huge windows—and oh! so furnished. Julia, with an unlimited allowance, arrived two days early and was attacked with a fever of settling.

We have new wall paper and Oriental rugs and mahogany chairs—not painted mahogany which made us sufficiently happy last year, but real. It ’s very gorgeous, but I don’t feel as though I belonged in it; I ’m nervous all the time for fear I ’ll get an ink spot in the wrong place.

And, Daddy, I found your letter waiting for me—pardon—I mean your secretary’s.

Will you kindly convey to me a comprehensible reason why I should not accept that scholarship? I don’t understand your objection in the least. But anyway, it won’t do the slightest good for you to object, for I ’ve already accepted it—and I am not going to change! That sounds a little impertinent, but I don’t mean it so.

I suppose you feel that when you set out to educate me, you ’d like to finish the work, and put a neat period, in the shape of a diploma, at the end.

But look at it just a second from my point of view. I shall owe my education to you just as much as though I let you pay for the whole of it, but I won’t be quite so much indebted. I know that you don’t want me to return the money, but nevertheless, I am going to want to do it, if I possibly can; and winning this scholarship makes it so much easier. I was expecting to spend the rest of my life in paying my debts, but now I shall only have to spend one-half of the rest of it.

I hope you understand my position and won’t be cross. The allowance I shall still most gratefully accept. It requires an allowance to live up to Julia and her furniture! I wish that she had been reared to simpler tastes, or else that she were not my room-mate.

This is n’t much of a letter; I meant to have written a lot—but I ’ve been hemming four window curtains and three portières (I ’m glad you can’t see the length of the stitches) and polishing a brass desk set with tooth powder (very uphill work) and sawing off picture wire with manicure scissors, and unpacking four boxes of books, and putting away two trunkfuls of clothes (it does n’t seem believable that Jerusha Abbott owns two trunks full of clothes, but she does!) and welcoming back fifty dear friends in between.

Opening day is a joyous occasion!

Good night, Daddy dear, and don’t be annoyed because your chick is wanting to scratch for herself. She ’s growing up into an awfully energetic little hen—with a very determined cluck and lots of beautiful feathers (all due to you).

Affectionately,Judy.September 30th.

Dear Daddy,

Are you still harping on that scholarship? I never knew a man so obstinate and stubborn and unreasonable, and tenacious, and bull-doggish, and unable-to-see-other-people’s-points-of-view as you.

You prefer that I should not be accepting favors from strangers.

Strangers!—And what are you, pray?

Is there any one in the world that I know less? I should n’t recognize you if I met you on the street. Now, you see, if you had been a sane, sensible person and had written nice, cheering, fatherly letters to your little Judy, and had come occasionally and patted her on the head, and had said you were glad she was such a good girl—Then, perhaps, she would n’t have flouted you in your old age, but would have obeyed your slightest wish like the dutiful daughter she was meant to be.

Strangers indeed! You live in a glass house, Mr. Smith.

And besides, this is n’t a favor; it ’s like a prize—I earned it by hard work. If nobody had been good enough in English, the committee would n’t have awarded the scholarship; some years they don’t. Also—But what ’s the use of arguing with a man? You belong, Mr. Smith, to a sex devoid of a sense of logic. To bring a man into line, there are just two methods: one must either coax or be disagreeable. I scorn to coax men for what I wish. Therefore, I must be disagreeable.

I refuse, sir, to give up the scholarship; and if you make any more fuss, I won’t accept the monthly allowance either, but will wear myself into a nervous wreck tutoring stupid Freshmen.

That is my ultimatum!

And listen—I have a further thought. Since you are so afraid that by taking this scholarship, I am depriving some one else of an education, I know a way out. You can apply the money that you would have spent for me, toward educating some other little girl from the John Grier Home. Don’t you think that ’s a nice idea? Only, Daddy, educate the new girl as much as you choose, but please don’t like her any better than me.

I trust that your secretary won’t be hurt because I pay so little attention to the suggestions offered in his letter, but I can’t help it if he is. He ’s a spoiled child, Daddy. I ’ve meekly given in to his whims heretofore, but this time I intend to be FIRM.

Yours,With a Mind,Completely and Irrevocably andWorld-without-End Made-up.Jerusha Abbott.

“I LIKE MY DIFFERENT FRIENDS TO KNOW EACH OTHER.”

November 9th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

I started down town to-day to buy a bottle of shoe blacking and some collars and the material for a new blouse and a jar of violet cream and a cake of Castile soap—all very necessary; I could n’t be happy another day without them—and when I tried to pay the car fare, I found that I had left my purse in the pocket of my other coat. So I had to get out and take the next car, and was late for gymnasium.

It ’s a dreadful thing to have no memory and two coats!

Julia Pendleton has invited me to visit her for the Christmas holidays. How does that strike you, Mr. Smith? Fancy Jerusha Abbott, of the John Grier Home, sitting at the tables of the rich. I don’t know why Julia wants me—she seems to be getting quite attached to me of late. I should, to tell the truth, very much prefer going to Sallie’s, but Julia asked me first, so if I go anywhere, it must be to New York instead of to Worcester. I ’m rather awed at the prospect of meeting Pendletons en masse, and also I ’d have to get a lot of new clothes—so, Daddy dear, if you write that you would prefer having me remain quietly at college, I will bow to your wishes with my usual sweet docility.

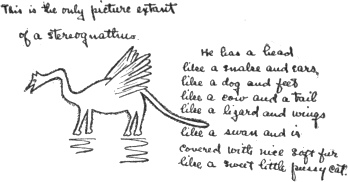

I ’m engaged at odd moments with the “Life and Letters of Thomas Huxley”—it makes nice, light reading to pick up between times. Do you know what an archæopteryx is? It ’s a bird. And a stereognathus? I ’m not sure myself but I think it ’s a missing link, like a bird with teeth or a lizard with wings. No, it is n’t either; I ’ve just looked in the book. It ’s a mesozoic mammal.

I ’ve elected economics this year—very illuminating subject. When I finish that I ’m going to take Charity and Reform; then, Mr. Trustee, I ’ll know just how an orphan asylum ought to be run. Don’t you think I ’d make an admirable voter if I had my rights? I was twenty-one last week. This is an awfully wasteful country to throw away such an honest, educated, conscientious, intelligent citizen as I would be.

Yours always,Judy.December 7th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

Thank you for permission to visit Julia—I take it that silence means consent.

Such a social whirl as we ’ve been having! The Founder’s dance came last week—this was the first year that any of us could attend; only upper classmen being allowed.

I invited Jimmie McBride, and Sallie invited his room-mate at Princeton, who visited them last summer at their camp—an awfully nice man with red hair—and Julia invited a man from New York, not very exciting, but socially irreproachable. He is connected with the De la Mater Chichesters. Perhaps that means something to you? It does n’t illuminate me to any extent.

However—our guests came Friday afternoon in time for tea in the senior corridor, and then dashed down to the hotel for dinner. The hotel was so full that they slept in rows on the billiard tables, they say. Jimmie McBride says that the next time he is bidden to a social event in this college, he is going to bring one of their Adirondack tents and pitch it on the campus.

At seven-thirty they came back for the President’s reception and dance. Our functions commence early! We had the men’s cards all made out ahead of time, and after every dance, we ’d leave them in groups under the letter that stood for their names, so that they could be readily found by their next partners. Jimmie McBride, for example, would stand patiently under “M” until he was claimed. (At least, he ought to have stood patiently, but he kept wandering off and getting mixed with “R’s” and “S’s” and all sorts of letters.) I found him a very difficult guest; he was sulky because he had only three dances with me. He said he was bashful about dancing with girls he did n’t know!

The next morning we had a glee club concert—and who do you think wrote the funny new song composed for the occasion? It ’s the truth. She did. Oh, I tell you, Daddy, your little foundling is getting to be quite a prominent person!

Anyway, our gay two days were great fun, and I think the men enjoyed it. Some of them were awfully perturbed at first at the prospect of facing one thousand girls; but they got acclimated very quickly. Our two Princeton men had a beautiful time—at least they politely said they had, and they ’ve invited us to their dance next spring. We ’ve accepted, so please don’t object, Daddy dear.

Julia and Sallie and I all had new dresses. Do you want to hear about them? Julia’s was cream satin and gold embroidery, and she wore purple orchids. It was a dream and came from Paris, and cost a million dollars.

Sallie’s was pale blue trimmed with Persian embroidery, and went beautifully with red hair. It did n’t cost quite a million, but was just as effective as Julia’s.

Mine was pale pink crêpe de chine trimmed with écru lace and rose satin. And I carried crimson roses which J. McB. sent (Sallie having told him what color to get). And we all had satin slippers and silk stockings and chiffon scarfs to match.

You must be deeply impressed by these millinery details!

One can’t help thinking, Daddy, what a colorless life a man is forced to lead, when one reflects that chiffon and Venetian point and hand embroidery and Irish crochet are to him mere empty words. Whereas a woman, whether she is interested in babies or microbes or husbands or poetry or servants or parallelograms or gardens or Plato or bridge—is fundamentally and always interested in clothes.

It ’s the one touch of nature that makes the whole world kin. (That is n’t original. I got it out of one of Shakespeare’s plays.)

However, to resume. Do you want me to tell you a secret that I ’ve lately discovered? And will you promise not to think me vain? Then listen:

I ’m pretty.

I am, really. I ’d be an awful idiot not to know it with three looking-glasses in the room.

A Friend.P. S. This is one of those wicked anonymous letters you read about in novels.

December 20th.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

I ’ve just a moment, because I must attend two classes, pack a trunk and a suitcase, and catch the four-o’clock train—but I could n’t go without sending a word to let you know how much I appreciate my Christmas box.

I love the furs and the necklace and the liberty scarf and the gloves and handkerchiefs and books and purse—and most of all I love you! But Daddy, you have no business to spoil me this way. I ’m only human—and a girl at that. How can I keep my mind sternly fixed on a studious career, when you deflect me with such worldly frivolities?

I have strong suspicions now as to which one of the John Grier Trustees used to give the Christmas tree and the Sunday ice-cream. He was nameless, but by his works I know him! You deserve to be happy for all the good things you do.

Good-by, and a very merry Christmas.

Yours always,Judy.P. S. I am sending a slight token, too. Do you think you would like her if you knew her?

January 11th.

I meant to write to you from the city, Daddy, but New York is an engrossing place.

I had an interesting—and illuminating—time, but I ’m glad I don’t belong in such a family! I should truly rather have the John Grier Home for a background. Whatever the drawbacks of my bringing up, there was at least no pretense about it. I know now what people mean when they say they are weighed down by Things. The material atmosphere of that house was crushing; I did n’t draw a deep breath until I was on an express train coming back. All the furniture was carved and upholstered and gorgeous; the people I met were beautifully dressed and low-voiced and well-bred, but it ’s the truth, Daddy, I never heard one word of real talk from the time we arrived until we left. I don’t think an idea ever entered the front door.

Mrs. Pendleton never thinks of anything but jewels and dressmakers and social engagements. She did seem a different kind of mother from Mrs. McBride! If I ever marry and have a family, I ’m going to make them as exactly like the McBrides as I can. Not for all the money in the world would I ever let any children of mine develop into Pendletons. Maybe it is n’t polite to criticize people you ’ve been visiting? If it is n’t, please excuse. This is very confidential, between you and me.

I only saw Master Jervie once when he called at tea time, and then I did n’t have a chance to speak to him alone. It was sort of disappointing after our nice time last summer. I don’t think he cares much for his relatives—and I am sure they don’t care much for him! Julia’s mother says he ’s unbalanced. He ’s a Socialist—except, thank Heaven, he does n’t let his hair grow and wear red ties. She can’t imagine where he picked up his queer ideas; the family have been Church of England for generations. He throws away his money on every sort of crazy reform, instead of spending it on such sensible things as yachts and automobiles and polo ponies. He does buy candy with it though! He sent Julia and me each a box for Christmas.