Полная версия:

Garden Birds

Globally, certain species are well represented within garden bird communities, including Rock Dove/Feral Pigeon Columba livia, House Sparrow and Starling Sturnus vulgaris (Aronson et al., 2014). Also widely represented – at least within the wider urban environment – are introduced or ‘invasive’ species such as Mallard Anas platyrhynchos, Canada Goose Branta canadensis, Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto and Ring-necked Parakeet Psittacula krameri, plus (in those places beyond their native range) House Sparrow, Starling and Rock Dove/Feral Pigeon. As a group, corvids appear to be well represented, as do pigeons and doves, leading some authors to suggest that urban bird communities globally are becoming more homogenous in their composition (either directly, in terms of particular species, or indirectly, through different species occupying similar ecological niches). This process is something that we will discuss in the next section.

FIG 4. Blackbird is best considered as an ‘urban adopter’, a species that is opportunistic in the way that it uses gardens and the resources that they offer. (John Harding)

The species of birds associated with the urban environment – of which gardens are a key component – can be divided into three main types. These are the ‘urban exploiters’, the ‘urban adopters’ and the ‘urban relicts’. Exploiters are those species, like Feral Pigeon, that are typically abundant within urban areas and which depend upon the anthropogenic resources available within the built environment. Adopters also make use of the resources but are more opportunistic in how they do this, and many of our familiar garden birds can be regarded as being of this kind – think of the Blackbirds Turdus merula and Siskins Spinus spinus that move into gardens during the winter months. Urban relict species are those whose population has managed to hang on within a fragment of their former habitat that is now contained within a wider urbanised landscape; such species tend to be found outside of western Europe, where new cities have emerged quickly within formerly wildlife-rich habitats. Another term that may be encountered when discussing urban bird populations is ‘urban avoiders’, those species that are absent or very poorly represented within the urban bird community.

The Rock Dove/Feral Pigeon is one of the oldest and most cosmopolitan commensal species, whose huge global population reflects early domestication and the subsequent transportation and introduction to sites across the world. The very high Feral Pigeon densities encountered in many cities is, to a large degree, a consequence of supplementary feeding and discarded human food, and the presence of buildings and other structures with an abundance of suitable nest sites. In some cities, such as Singapore, these populations are derived from the rapid expansion of a genetically homogenous group of founder individuals (Tang et al., 2018), underlining how a species can very rapidly colonise an urban area given favourable conditions. Similar patterns may be seen in introduced populations of House Sparrow, Starling and Collared Dove.

The notion that species found in a high proportion of the world’s cities, such as Starling, are successful generalists and able to breed anywhere, does require some refinement. Work by Gwénaëlle Mennechez and Philippe Clergeau has, for example, revealed that while the abundance of breeding Starlings does appear to be similar throughout the urbanisation gradient, the degree of urbanisation still has a measurable negative impact on its breeding success. Working in western France, Mennechez and Clergeau (2006) found that the amount of food delivered to Starling nestlings in more urbanised areas was significantly lower than that delivered elsewhere along the urbanisation gradient, resulting in smaller nestling masses. These urban Starlings were found to produce fewer young, each of seemingly lower quality; while they were able to maintain breeding populations in these highly urban habitats, the species was not as successful as a simple measure of breeding abundance might suggest. This is something to which we will return in Chapter 3.

URBAN BIRD COMMUNITIES

Surprisingly perhaps, one in five of the world’s 10,000 or so bird species is found in the highly urbanised landscapes of major cities, including 36 species that have been identified by the IUCN global Red List as threatened with extinction. (Aronson et al., 2014). Globally, the species richness of urban bird communities ranges from 24 species to 368, with a global median of 112.5 species (Aronson et al., 2014). As just noted, a number of studies, typically involving work carried out within a single city, have suggested that the process of urbanisation results in urban bird communities that are becoming increasingly similar over time, and dominated by a few key species. This process is known as homogenisation and is thought to come about because urbanisation not only extirpates native species from an area but also promotes the establishment of non-native species capable of adapting to the new conditions (Luck & Smallbone, 2010). Although these new conditions tend to be similar in cities across the world, they do not in themselves promote the same species winners; instead, it is our preference for certain species (transporting them to new settlements) that has resulted in the homogenisation seen at a global scale (McKinney, 2006).

In their review of the bird communities of 54 cities, spread over 36 countries and 6 continents, Aronson et al. (2014) found that cities tended to retain similar compositional patterns within their distinct biogeographic regions. While certain non-native species were shared across many of the cities studied, the urban communities had not yet become taxonomically homogenised at a global scale – they retained the characteristics of their local region pool. Four species were found in more than 80 per cent of the cities examined; these being the familiar Feral Pigeon, House Sparrow, Starling and Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica. With the exception of Australasia, the proportion of non-native species found within each urban community was similar (at 3 per cent), Australasia being somewhat higher because of the large number of non-native species introduced into New Zealand by settlers. Work within Europe (Jokimäki & Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, 2003; Clergeau et al., 2006) suggests that urbanisation here might bring about homogenisation by decreasing the abundance of ground-nesting species and those preferring bush-shrub habitats, but also noting that it is difficult to generalise because of the effects of latitude and diversity in the urban habitats studied.

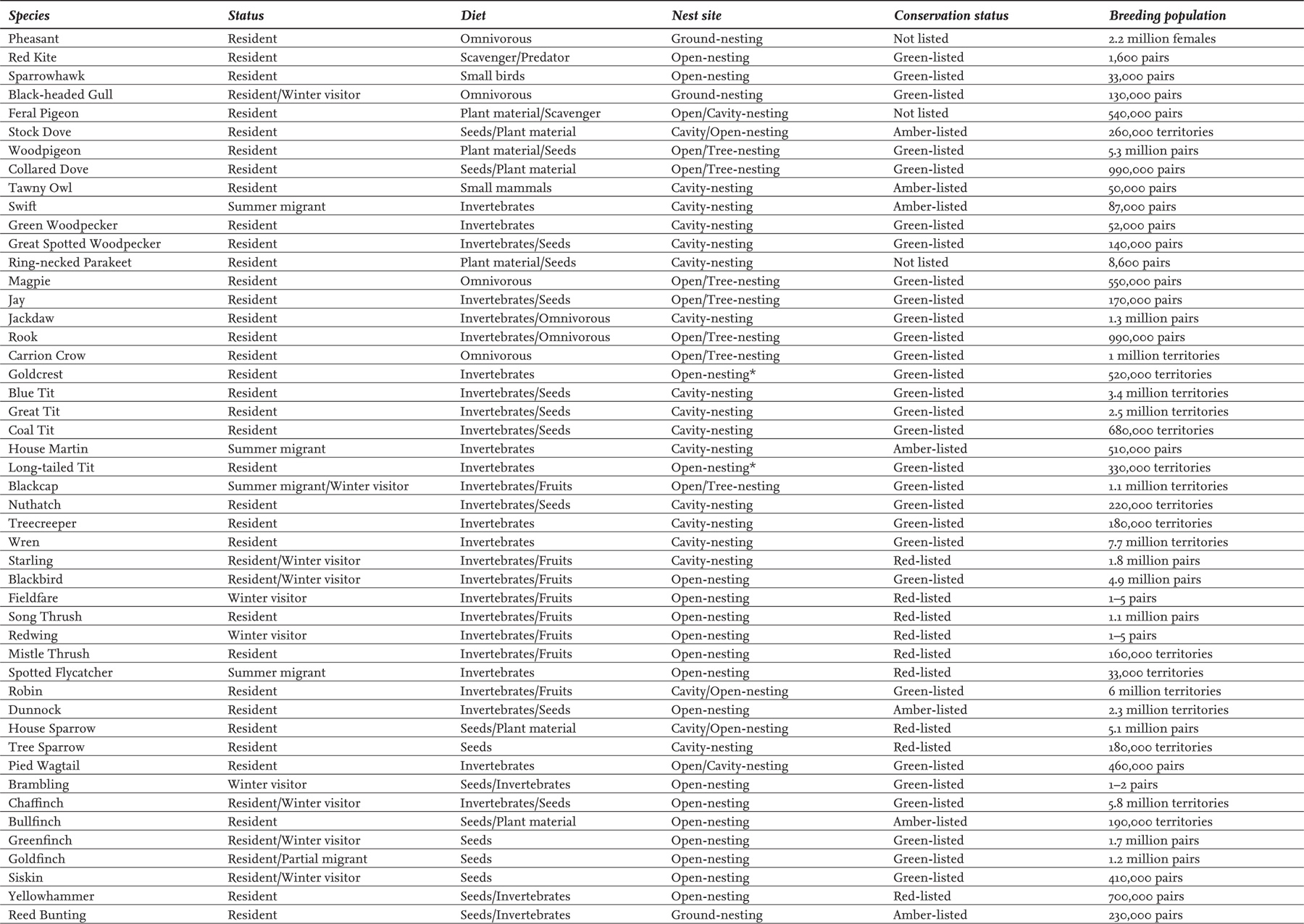

What is interesting about species seemingly well adapted to the urban environment is that they tend to share a number of traits (Leveau, 2013). They tend to be omnivorous in their diet, largely sedentary in habits and able to utilise a range of artificial nesting sites (Máthé & Batáry, 2015). Table 1 highlights the broad ecological traits of the garden bird species considered in this book. As we have seen, omnivores and granivores (seed-eating species) tend to dominate the garden bird community, with insectivores often poorly represented. This suggests that invertebrate populations within gardens and the wider urban environment may not be sufficient to support populations of insect-eating birds. It also has implications for breeding success more widely, since most small birds feed their chicks on invertebrates. Work by Croci & Clergeau (2008) also suggests that ‘urban adapter’ species are those that are sedentary in habits and omnivorous, though with the additional traits of preferring forest environments, being widely distributed, and being high-nesters with large wingspans. Croci & Clergeau (2008) also note that ‘urban avoider’ species tend to be those that allocate more energy to their breeding attempts than ‘urban adaptor’ species, a trait that might make it difficult for them to adapt to new environments. Logically, given the absence of larger and older trees with natural cavities, you might predict cavity-nesting birds to be less common in urban environments. However, the presence of substantial numbers of nest boxes appears to help at least some of these species, most notably the tits, though those requiring large cavities often lose out.

TABLE 1. Common garden birds, their ecological traits and status. * Goldcrest and Long-tailed Tit are open-nesting species, whose nest is fully domed. Conservation status is derived from the Birds of Conservation Concern (BOCC) List, which classifies species as Red-, Amber- or Green-listed based on a number of criteria. Non-native species with feral populations are not assessed by BOCC.

That wild birds can take advantage of the opportunities afforded by human activities is evident from changes in urban-nesting gull populations within the UK, which have increased substantially over a short period of time; this increase has occurred despite the fact that coastal populations of the same species have been in decline. It is thought that much of this increase has been driven by the availability of food scraps on our urban streets and at landfill sites, coupled with the relatively predator-free nesting opportunities available (Ross-Smith et al., 2014).

Interestingly, much of the ecological work looking at urban birds has tended to adopt a binary approach, separating species into urban and non-urban classes and then looking for differences in their ecological and/or physiological traits (e.g. Møller, 2009). Such work has underlined, for example, that insectivores, cavity nesters and migrants are under-represented within urban bird communities, while species showing high rates of feeding innovation, high annual fecundity and high adult survival rates are over-represented. However, such an approach – where species are lumped into one or the other of these two groupings – fails to account for important differences in how individual species may respond to urbanisation, or to differences in how a species may respond in different parts of its geographic range. When you consider these differences, then many of the identified traits characteristic of one or other community disappear (Evans et al., 2011).

The nature of urban bird communities has been the subject of study and review for a number of years and several common patterns emerge. It appears, for example, that local factors are more important in determining the species richness of these communities than factors operating at a wider regional scale, and that urban communities respond positively to the availability of supplementary feeding and the structural complexity of local habitat, but negatively to the degree of human disturbance (Evans et al., 2009a). While there is likely to be continuing debate around this topic (e.g. Møller, 2014), it does appear that, at the species level, generalists are better suited to the urban environment than specialists, as are those species that nest off the ground. Generalist species are known to be less susceptible to, and may even benefit from, environmental disturbance of the sort associated with urbanisation (McKinney & Lockwood, 1999), and they are also the species that appear to be coping best with a changing global climate (Davey et al., 2012), something that may also be behind their apparent success in our towns, cities and gardens. Broader environmental tolerance is something that has been demonstrated in urban birds, most clearly through a study by Frances Bonier and colleagues, who compared the elevational and latitudinal distributions of 217 urban birds found in 73 of the world’s largest cities with the distributions of 247 rural congeners. The results of this work showed that urban bird species had markedly broader environmental tolerance than rural congeners, suggesting that a broad environmental tolerance may predispose some species to thrive within urban habitats (Bonier et al., 2007).

UK GARDEN BIRDS, THE SIZE OF THEIR POPULATIONS AND COMMUNITY STRUCTURE

The BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) is the core scheme used to monitor the population trends of a broad range of breeding bird species across the UK. Some 3,000 participants visit randomly selected 1-km survey squares and record the bird species that they encounter there. The birds seen are recorded in a series of distance bands running out parallel to the line transects along which each observer walks. This approach, coupled with the collection of habitat information for each of the transect sections, allows researchers to calculate density estimates by habitat for each of the bird species commonly recorded. These can then be multiplied up by the area of each habitat type nationally to calculate population estimates based on habitat type, which in turn provide a sense of the bird populations associated with gardens and wider urbanised landscapes (Newson et al., 2005).

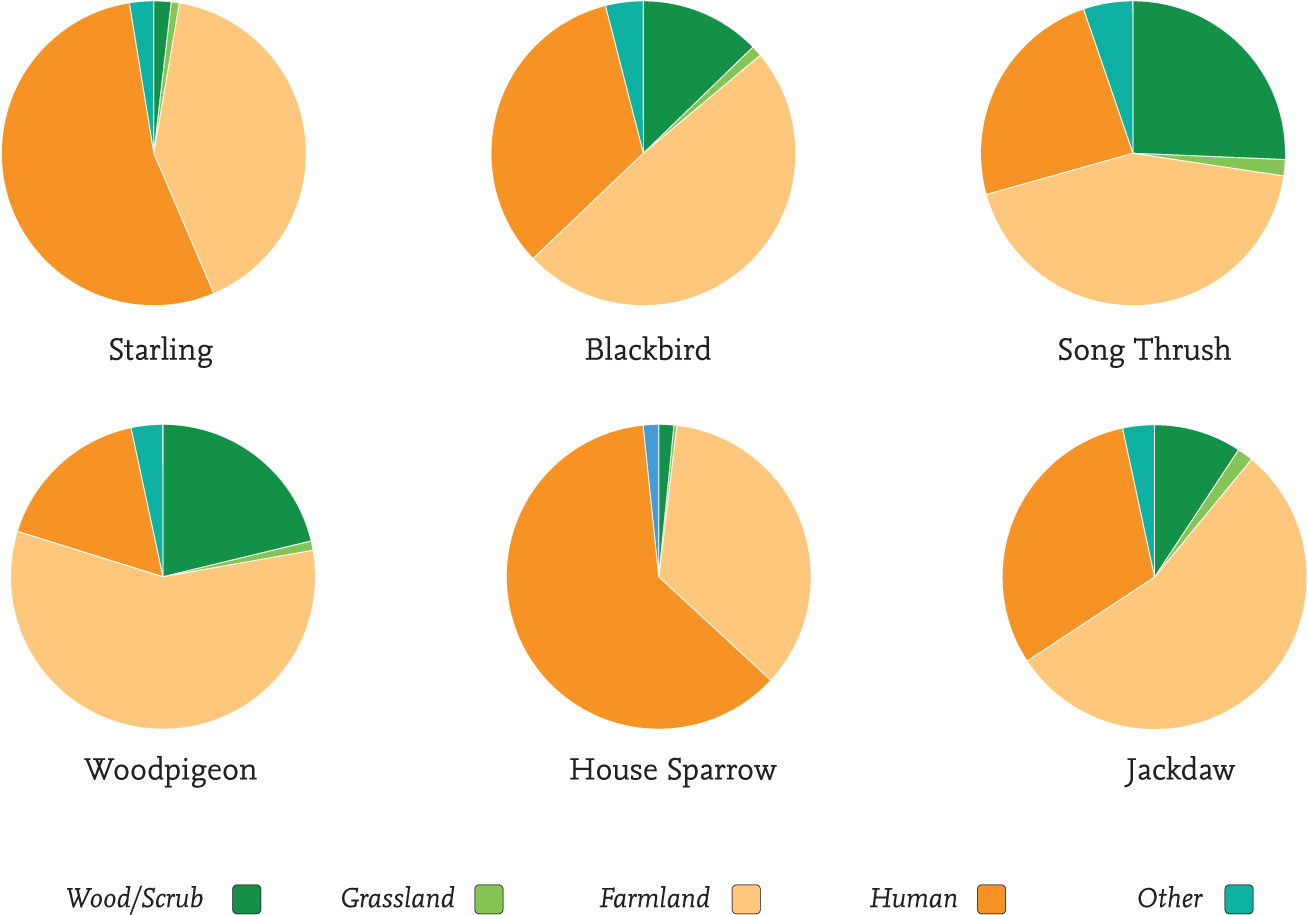

FIG 5. Data from the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey underline the sizeable populations of certain species breeding in urbanised landscapes. Redrawn from data presented by Newson et al. (2005).

This approach suggests that some of the national population estimates previously given for familiar species, like Blackbird, Starling, House Sparrow, Greenfinch Chloris chloris, Jackdaw Crovus monedula and Woodpigeon Columba palumbus, have been underestimated because the built environment and its gardens had not been properly taken into account. The BBS habitat-based approach indicates the importance of urban, suburban and rural human habitats for species like House Sparrow and Starling, which have 61.5 per cent and 53.9 per cent respectively of their breeding population found here. The survey has also enabled the production of figures suggesting that the habitats directly associated with human sites (urban, suburban and rural) could represent 27,919 km2 (2,791,900 ha) or 10.9 per cent of UK land area. This can be further broken down as urban (2.2 per cent), suburban (5.1 per cent) and rural human sites (3.6 per cent). The figure of 10.9 per cent is somewhat higher than the 6 per cent figure that has been derived from the Corinne Land Cover map. Given the different assumptions involved, it seems likely that the true figure lies somewhere between the two approaches and possibly closer to the 6 per cent derived from satellite imagery. Using the figure of 432,964 ha, presented at the top of this chapter and calculated by Davies et al. (2009) for the area of UK gardens, and the two figures just mentioned (Newson et al. 2,791,900 ha, Land Cover map 1,454,970 ha) for the amount of built-upon land, suggests that gardens might represent between 16 per cent and 30 per cent of the land area present within UK cities, towns and villages, and 1.79 per cent of total land area.

Gardens and their associated houses are of particular importance to House Martin and Swift, two species that national monitoring schemes like the Breeding Bird Survey struggle to monitor. While these two summer visitors are clearly dependent upon buildings for the nesting opportunities that they provide, the nature of the surrounding gardens is much less important. Resident species, such as House Sparrow and Starling, also make use of domestic dwellings for their nesting opportunities but are more closely tied to the nature of the gardens within which these dwellings are located. The presence of shrubby cover is important for House Sparrow, while Starlings appear to favour properties where there is access to nearby areas of short vegetation – such as garden lawns or amenity grassland. Another summer migrant, the Spotted Flycatcher, also appears to be dependent on the nature of the gardens it occupies, seemingly preferring rural or larger suburban gardens with mature trees and an abundance of small flying insects.

A number of bird species use gardens at a particular time of the year, arriving to take advantage of feeding opportunities when conditions elsewhere become less favourable. This is something that we will examine in greater detail in Chapter 2 but it is worth noting here how the early winter arrival of migrant thrushes and finches boosts resident populations and sees birds taking windfall apples and the fruits of berry-producing shrubs. Joining these less obvious visitors (which look the same as year-round residents, such as Blackbird and Chaffinch Fringilla coelebs) are more obvious migrants, including Brambling, Redwing, Fieldfare and Waxwing. Such species tend to forage over large areas, responding to the availability of favoured foods, and so are able to take advantage of the seasonal resources present in many gardens.

COMMUNITY STRUCTURE AND GARDEN TYPES

As the figures produced by Newson et al. (2005) illustrate, the garden bird community contains a significant component of the wider breeding populations of a number of key species. In addition, Newson et al.’s work underlines that many garden species also occur alongside one another within other communities – such as the farmland bird community and the woodland bird community. There may be differences between these communities in terms of species interactions, such that one species does better than another in one habitat but not elsewhere. Such differences in community structure can also be seen from smaller and more focussed studies. Work on tit populations across different UK habitats reveals that Great Tits usually outnumber Blue Tits in woodland populations, often by 2:1 or more. In a suburban population studied by Cowie & Hinsley (1987), the situation was reversed, with Blue Tit outnumbering its larger relative by 3:1 or more. This suggests that Blue Tits might be better suited to the urban environment than Great Tits.

Gardens vary greatly in their size and structure, and consequently in their use by birds. Although we often categorise gardens into urban, suburban and rural, this is a rather simplistic approach and fails to adequately account for the variation that exists both within individual gardens and in the wider habitat framework within which they sit. Within the UK, as much as 7 per cent of land area may be located within towns and cities with a human population in excess of 10,000 people. Some 80 per cent of the UK population lives in these areas, with 40 per cent of the population living within London and our other major conurbations. In an attempt to document the extent and structure of the gardens associated with these conurbations, Alison Loram and colleagues at the University of Sheffield took a detailed look at the cities of Edinburgh, Belfast, Oxford, Cardiff and Leicester (Loram et al., 2007). The researchers surveyed a sample of at least 500 properties from each of the five cities, revealing that 99 per cent had an associated garden. The size of the gardens – whose median areas varied across the different cities, from 96.4 m2 (Belfast) to 213.0 m2 (Edinburgh) – was closely related to the type of housing present; the general pattern revealing that garden size roughly doubles as you move from terrace housing, to semi-detached to detached. Relatively small gardens (<400 m2) were much more numerous within the cities than larger gardens, contributing disproportionately to the total garden area present. This has important consequences for engaging householders in nature conservation through practices such as wildlife-friendly gardening (see Chapter 6), because a small garden might not seem particularly important in a wider context to a householder. I have often heard the phrase ‘what difference can I make; my garden is only small’ but it is important to remember that individual gardens do not exist in isolation; they are instead part of a wider ecological network.

FIG 6. Blue Tits typically outnumber Great Tits in the urban environment, by as much as 3:1, but are the less numerous species within traditional woodland habitats. (John Harding)

Loram’s work also revealed the spatial pattern of gardens within each of the cities, reflecting variation in the density of the human population and the associated densities of housing stock. The history of each city, together with the geography of its location, contributed to the pattern of housing seen; the notion of a simple gradient in garden size, from the leafy suburbs with their large gardens through to courtyard gardens in the urban centre, was disrupted by these and other factors. This also meant that there was no clear relationship between garden size and distance to the edge of the conurbation within any of the five cities studied. This is important when we look at urban bird populations in more general terms as, for example, examined through the work of Chamberlain et al. (2009a) and others.

At a wider spatial scale, it is possible to use data from the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey to examine the densities of bird species across the broader landscape and, as was done by Tratalos et al. (2007), to look at the relationship between avian abundance, species richness and housing densities within urban areas. Tratalos et al. (2007) found that total species richness – and that of 27 urban-indicator species – increased from low to moderate household densities, before then declining as you reached higher household densities. Avian abundance showed a rather different pattern, increasing across a wider range of household densities and then only declining at the highest household densities. The researchers were also able to look at the patterns in abundance seen within individual species, highlighting some interesting differences between them. Importantly, however, most of the species showed a hump-shaped relationship with household density, declining at the highest densities. A somewhat worrying finding, highlighted by the team, was that avian abundance almost invariably began to decline at a point below the density of housing required by the UK government for new developments.

A number of studies have highlighted that within cities it is the suburbs that support the greatest variety of bird species, something that is reflected in the hump-shaped distribution of the relationship between species richness and housing density mentioned above. A widely accepted hypothesis for the shape of this relationship is that the observed pattern is due to the increased habitat heterogeneity present at intermediate levels of urbanisation – i.e. that the suburbs are more diverse than either the more urbanised town centres or the farmland habitats that so often surround our towns and cities. However, it may also be the case that there is a higher availability of food resources in our suburbs than elsewhere (see Chapter 2) and that this, rather than habitat heterogeneity, shapes species richness.

Where a garden is located along the rural to urban gradient may influence the community of garden birds associated with it. This is something that we have been able to examine by using data from the BTO’s Garden BirdWatch project (Chamberlain et al., 2004a). Looking at nearly 13,000 garden sites contributing weekly data on garden birds between 1995 and 2002, we examined the extent to which the occurrence of individual garden bird species at a site was determined by features within the garden itself or by the nature of the surrounding landscape. Garden size was taken into account because we found that, in most cases, species were more likely to occur in large gardens (and larger gardens were more likely to occur in rural habitats and to have high tree and hedge cover). Exceptions to this were House Sparrow, Collared Dove, Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus and Starling, all of which were more likely to occur in small gardens.

FIG 7. Analysis of BTO Garden BirdWatch data revealed that while most bird species were associated with larger gardens, Starling was one of four species found to be more likely to occur in smaller gardens. (Jill Pakenham)

Once we had controlled for the effects of garden size and the provision of food at garden feeding stations, we found that the likelihood of many species occurring in gardens was dependent on the nature of the surrounding local habitat rather than on features within the garden itself. We found that 12 of the 40 species examined were most likely to occur where the habitat outside the garden was rural in nature – these included open-nesting passerines associated with woodland or woodland edge (Wren, Robin, Blackbird, Blackcap Sylvia atricapilla and Chaffinch), hole-nesting (Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major, Blue Tit and Coal Tit Periparus ater) or farmland (Pied Wagtail Motacilla alba, Rook Corvus frugilegus, Greenfinch, Goldfinch Carduelis carduelis and Yellowhammer Emberiza citrinella). Just seven species showed a probability of occurrence that was highest in gardens located within urban habitats, these being House Sparrow, Feral Pigeon, Starling, Magpie Pica pica, Black-headed Gull, Woodpigeon and Collared Dove.