Полная версия:

Cultural traditions and the origin of the Indo-Europeans

All this is most reminiscent of Andronovo tradition-also indicated by the obligatory presence in burials of vessels and adornments, embellished with ornamental motives that are more than traditional of Andronovo artifacts.

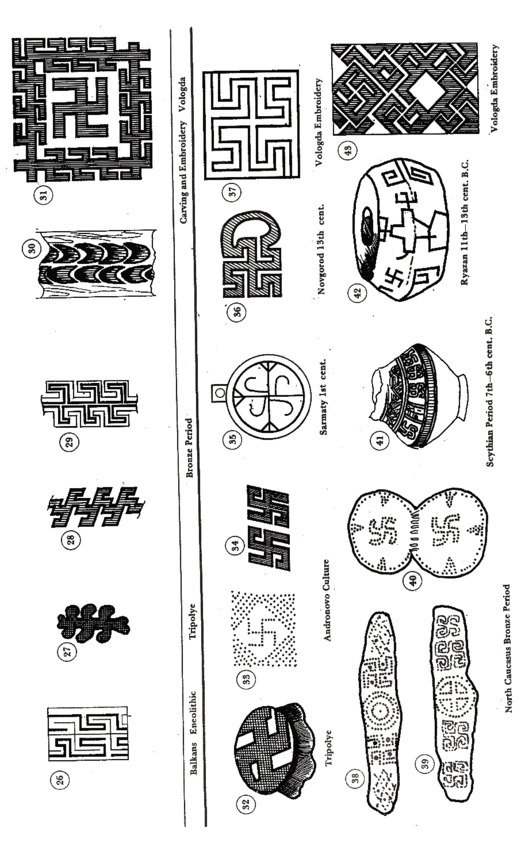

In all likelihood analogous functions were discharged by the sheet bronze diadems embellished with an ornamental pattern identical with the decor of the double oval Lugovoi plaques, which B. Tekhov recovered from the TH graves in Northern Ossctia (Figs. 38 and 39). These diadems are decorated with circle”, triangles and lo/rn^es; m«l also an a rule with meander and swastika typo motives.

Tekhov says that similar diadems were recovered from a Styrfaz chamber-tomb in the Northern Caucasus, from the Armenian village of Geharot and from sites in Azerbaijan and Iran.

He has also indicated the characteristic meander and swastika motives on the Koban-type axes recovered from the same Tliburials.

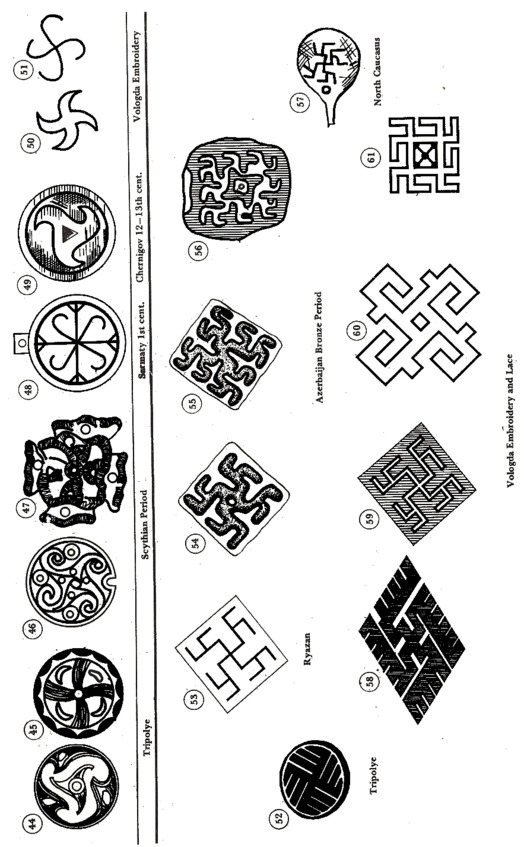

Swastika-type motives complicated by many protruding lines are also to be observed in the decor of finds unearthed in a number of places in Azerbaijan as for instance, on a clay die and also on the walls of a temple and in the plaster work of an earth dwelling from the ancient village of Sary-Tepe, on the wall by a hearth (Fig. 29) and the pintaderas (Figs. 54—56) of the village of Babadervish, which date back to the 12th-8th centuries B.C.

Consequently, the archaeological finds made in the Northern Caucasus and partly in the Trans-Caucasus, in Armenia and Azerbaijan, provide us with specimens of the use of ancient sacred ornamental motives that are characteristic of Mezin site artefacts decor and of Tripolye-Cucuteni, Timber-Frame and, especially, Andronovo pottery. Moreover, in the Caucasus these motives most likely have the same sacred functions of talisman and possibly of tribal and clan totem as were characteristic of Andronovo and, likely, Tripolye cultures.

We encounter echoes of swastika motives in Scythian jewelry, more specifically in the decor of horse trappings recovered from the Northern Pontine area. A. Meliukova believes that the openwork swastika plaques, also to be encountered in Thracian hoards are of Scythian origin, and adds that they appeared in the Northern Pontine area in the late 6th century B.C. True, in Scythian art, all these forms have been markedly modified and transmuted (Fig. 47) to meet requirements of the conventionalized realistic trend known as the Scytho-Siberian Animal Style.

We would now like to turn to the Vologda material. The appended table furnishes specimens of the traditional ornamental motives of peasant embroideries and ornamental weaving, common in the North-Eastern districts of Vologda region. We noted earlier what the historical and ethnic situation in these parts was like and we have no reason to question the Slav, or rather, East-Slav, Russian origin of these ornamental patterns. All the samples supplied are details of elaborate ornamental patterns that embellished headgear, sashes and belts, aprons, shirts and blouses and towels, items mostly sacred that beside having a purely domestic usage were talismans. One must say that the resemblance is amazing. As in the entire range of the Andronovo decor, in North-Russian embroidery and ornamental weaving, too the compositions are divided into three horizontal registers with the often repetitive top and bottom two enclosing the central register that as a rule displays the vital most designs from the angle of semantic significance. This is precisely where we encounter a diversity of meandr and swastika motifs (Fig. 51) which are absolutely identical with the Tripolye (Fig.52) and Amlronovo (Figs. 33 and 34) decor as well as with the North Caucasian and Trans-Caucasian motifs of the 13th-8th centuries B.C. and Scythian décor {Fig. 41). Thus, if the ornament from the Babader vish site. (Fig. 29) embellished the wall behind the altar in a 12th-8th centuries B.C. dwelling had an unquestionably ritual significance the absolutely identical pattern, a composition of lozenges, which adorns the hem of a North-Russian peasant woman’s blouse, is also of a ritual nature (Fig. 31).

The design on the pintadera from the same site has an affinity with the pattern of a wedding towel (Fig. 61) and with the design on the stitched inset for a Vologda towel (Fig. 59). Further, the detail from the ornamental pattern of an Andronovo vessel (Fig. 18) is almost identical with that of the embroidered hem of a blouse (Fig. 24), while the embroidered towel end (Fig. 5) is absolutely identical with the intricate meander weave that embellishes an Andronovo clay vessel of the middle of the 2nd millennium B.C. (Fig. 4) etc. etc. (see Figs. 19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 30 and 60). The existence of such affinities is likewise confirmed by east Slav archaeological finds. Thus, the intricate swastika on the clasp or buckle of 1220—1260 (discovered in the late 1960s at the Tikhvin digs in Novgorod (Fig. 36), is identical with the motif that the Vologda peasant woman U. Terebova employed in the 1910s for the wedding towel of her daughter (Fig. 37). Most exciting in this respect is the slate spindle whorl, carrying a scratched design in the form of a six-armed Orthodox cross enclosed within spiral meanders and swastikas that was unearthed at a Slav farming site of the 11th-13th centuries near Ryazan and published by G. Polyakova (Fig. 42).

The list could be greatly extended. However we shall merely state that while with different nations similar ornamental patterns may converge, one is hard put to believe that peoples thousands of kilometers and thousands of years apart could-if they are not ethnogenetically linked-invent quite independendy of one another such intricate ornamental patterns, which are identical down to the smallest detail and which, furthermore, discharge the same ritual functions of talisman and totem.

Refraining from far-reaching conclusions, we shall merely note that as our analysis is restricted to the steppes and forest-steppes of the USSR, we have not invoked analogous Indian and Persian items, if we did so the appended table of affinities would be much longer. It is our profound conviction, however that, such material should be invoked as representing a most serious problem for the science of history in the foreseeable future. The affinities to be observed in the spiritual and material cultures of the ancient Slavs and, for instance, of the peoples of North Western and Western Indian and Iran-both in olden times and partially today-are too numerous to be ignored.

Currently, Soviet archaeologists have amassed a wealth of evidence warranting the assumption that actively involved in the ancient cultures mentioned above were the carriers of the ancient forms of Indo-Iranian or Aryan47 languages.

Thus Ye. Kuzmina says: “Evidently an in-depth, research, into the Indo-Iranian traditions of the visual arts imagery semantics-for which archaeology has already yielded plentiful evidence-will be crucial studying the intricate ethnic history of Southern-Central Asia and Afghanistan” It must necessarily be added that the quoted region likewise incorporates the vast expanses of the Eurasian steppes and forest steppes.

Notes

Стасов В. В. Русский народный орнамент. Шитье, ткани, кружево. Вып. I. СПб. 1872.

Шаховская С. Н. Узоры старинного шитья в России. М. 1885.

Сидамон-Эристова В. П., Шабелъская Н. П. Собрание русской старины. Вып. I. Вышивки и кружева. М. 1910.

Амброз А. К. Раннеземледельческий культовый символ “ромб с крючками”. “Советская археология” (СА). 1965. №3.

Амброз А. К. О символике русской крестьянской вышивки архаического типа. СА. 1966. №1

Маслова Г. С. Орнамент русской народной вышивки. М. Наука. 1978.

Рыбаков Б. А. Космогония и мифология земледельцев энеолита. СА. 1965. №1.

Рыбаков Б. А. Макрокосм в микрокосме народного искусства. Декоративное искусство СССР. 1975. №1, 3.

Рыбаков Б. А. Происхождение и семантика ромбического орнамента. Сб. трудов НИИХП. М. 1972. вып. 5.

Рыбаков Б. А. Язычество древних славян. М. Наука. 1981.

Бибикова В. И. О происхождении мезинского палеолитического орнамента. СА. 1965. №1.

Граков Б. Н. Ранний железный век. М. изд. МГУ. 1977.

Киселев С. В. Древняя история Южной Сибири. М-Л. АН СССР.1949. Косарев М. Ф. Бронзовый век Западной Сибири. М. Наука. 1981.

Стоколос В. С. О стратиграфии поселения Кипель. СА. 1970. №3.

Арсланова Ф. X. Памятники андроновской культуры из Восточно-Казахстанской области. СА. 1973. №4.

Членова Н. Л. Распространение и пути связей древних культур Восточной Европы, Казахстана, Сибири и Средней Азии в эпоху поздней бронзы. Средняя Азия и ее соседи в древности и средневековье. М. Наука. 1981. Карта 1. Распространение черкаскульских, курмантау, федоровских, алакульских, срубных и абашевских памятников на территории СССР.

Грязное М. П. Этапы развития хозяйства скотоводческих племен Казахстана и Южной Сибири в эпоху бронзы. КСИЗ. 1957. вып. XXVI.

Хлобыстина М. Д. Некоторые особенности андроновской культуры Минусинских степей. СА. 1973. №4.

Маркович В. И. Склепы эпохи бронзы у сел. Энгикал в Ингушетии. СА. 1970. №4.

Маркович В. И. Степи и Северный Кавказ. Об изучении взаимосвязей древних племен. Восточная Европа в эпоху камня и бронзы. М. Наука. 1976. Мунчаев Р. М. Луговой могильник (исследования 1956—1957 гг.). Древности Чечено-Ингушетии. М. изд. АН СССР. 1963.

Техов Б. В. Тлийский могильник и проблема хронологии культуры поздней бронзы-раннего железа Центрального Кавказа. СА. 1972. №3.

Вели Алиев. Археологические раскопки в урочище Бабадервиш. СА. 1971. №2.

Мелюкова А. И. К вопросу о взаимосвязях скифского и фракийского искусства. Скифо-сибирский звериный стиль в искусстве народов Евразии. М. Наука. 1976.

Дьяконов И. М. Восточный Иран до Кира (к возможности новой постановки вопроса). История Иранского государства и культуры. М. 1971.

Кузьмина Е. Е. Происхождение индоиранцев в свете новейших археологических данных. Этнические проблемы истории Центральной Азии в древности (II тыс. до н. э.). М. 1981.

On the possible location of the holy Hara and Meru Mountains in Indo-Iranian (Aryan) mythology. 1986

The location of the legendary Hara and Meru, the holy northern mountains of the Indo-lranian (Aryan) epos and myths is one of the many riddles in Eurasian ancient history that has been troubling researchers for over a century and prompting ever more, sometimes totally contradictory, hypotheses. As a rule, they are believed to be the Scythian Ripei or Hyperborei mountains mentioned by the authors of antiquity. Over 80 years ago The Arctic Home in the Vedas, by the outstanding Indian political figure, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, launched a series of publications related to this subject in one way or another and continued to this day.

The answer has never been found, as obvious from the two most recent publications – a book by G. Bongard-Levin and E. Grantovsky From Scythia to India (1983), The Ethnogeography of Scythia by I. Kuklina (1985). The two socalled Ripei Mountains locations, which the books propose, are mutually exclusive, though the authors proceed from the same ancient myths, historical sources and data.

Bongard-Levin and Grantovsky, analyzed the Avesta, Rigveda, Mahabharata,

the works of Herodotus, Pomponius Mela, Plinius, Ptolemaeos, and the information provided by medieval Arabian travelers, ibn-Faldan, ibn-Batuta, and concluded that the geographical characteristics, repeated without exception in every source, are factual a/id indicate that the Ripei Mountains, Hara and Meru were the Urals, since only they possess nearly all the specific features attributed to the holy northern mountains: high altitude, natural resources, proximity to northern seas, etc.

Kuklina, the author of The Ethnogeography of Scythia, disagrees entirely, and argues that “it is apparently necessary to first distinguish the concept of the mythical northern mountains from that of mountains north of Scythia where many

rivers began. Both of them were named Ripei. However there is no doubt that only the latter mountains can be localized, whereas the former, connected with the far north and Hyperborei, should be sought for in the myths of Indo-lranian peoples”.

Kuklina backs up her conclusions with a large number of comments by ancient authors – Pseudo Hippocrates, Dionisius, Eustaphius, Vergilius, Plinius, Herodotus, etc. – about the northern mountains called Ripei. She then cites, from Bongard-Levin and Grantovsky, examples of amazing similarities between Scythian polar concepts and ancient Indian and ancient Iranian “Arctic” tradition.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги

Всего 10 форматов