Полная версия

Полная версияThe Harbor of Doubt

It seemed as though the opaque walls about him held in the sound as heavy curtains might in a large room; it fell dead on his own ears without any of the reverberant power that sound has in traveling across water.

Once more he listened. He knew that the schooner, being at anchor, would be ringing her bell; but he hardly hoped to catch a sound of that. Instead, he listened for the answering peal of a horn in one of the other dories. Straining his ears, he thought he caught a faint toot ahead of him and to starboard.

He seized his oars and rowed hard for several minutes in the direction of the sound. Then he stopped, and, rising to his feet, sent another great blast brawling forth into the fog. Once more he listened, and again it seemed as though an answering horn sounded in the distance. But it was fainter this time.

A gust of wind, rougher than the others, swirled the fog about him in great ghostly sheets, turning and twisting it like the clouds of greasy smoke from a fire of wet leaves. The dory rolled heavily, and Code, losing his balance, sprawled forward on the fish, the horn flying from his hand overboard as he tried to save himself.

For a moment only it floated; and then, as he was frantically swinging the dory to draw alongside, it disappeared beneath the water with a low gurgle.

The situation was serious. He was unable to attract attention, and must depend for his salvation upon hearing the horns of the other dories as they approached the schooner. Rowing hard all the time, with frequent short pauses, he strained his ears for the welcome sound.

Sometimes he thought he caught a faint, mellow call; but he soon recognized that these were deceptions, produced in his ears by the memory of what he had heard before. Impatiently he rowed on.

After a while he stopped. Since he could not get track of any one, it was foolish to continue the effort, for every stroke might take him farther and farther out of hearing. On the other hand, if he were headed in the right direction, another dory, trying to find the schooner, might cross his path or come within earshot.

He was still not in the least worried by the situation. Men in much worse ones had been rescued from them without thinking anything of them.

But the rising wind and sea gave him something to think of. The waves found it a very easy matter to climb aboard the heavily laden dory, and occasionally he had to bail with the can in the bows provided for the purpose.

An hour passed, and at the end of that time he found that he was bailing almost constantly. There was only one thing to do under the circumstances. The gaff lay under his hand. This is a piece of broom-handle, to the end of which a stout, sharp hook is attached, and the instrument is used in landing fish which are too heavy to swing inboard on the slender fishing-line.

Code took the gaff and commenced to throw the fish over the side one at a time. He hated the waste of splendid cod, but things had now got to a pass where his own comfort and safety were at stake. Once the fish were gone, with the cleanliness of long habit, he swabbed the bottom and sides of the dory with an old rag and rinsed them with water which he afterward bailed out.

The dory now rose high and dry on the waves; But Code found it increasingly difficult to row because the water tended to “crab” his oars and twist them suddenly out of his hands.

To keep his head to the wind he paddled slowly, listening for any sound of a boat.

Another hour passed and darkness began to come down. The pearly gray fog lost its color and became black, like smoke from a burning oil-tank. He knew the sun was below the horizon. He wondered if any of the other men had been caught. If none were gone but himself, he reasoned, the schooner would have come in search of him.

So, from listening for the horn of a dory, he tried to catch the hoarse voice of a patent fog-horn that would be grinding on the forecastle head.

By this time the wind was a gale, and he knew it was driving him astern, despite his rowing. The waves were no longer the little choppy seas that the Lass had encountered since leaving Freekirk Head, but hustling, slopping hills that attacked him in endless and rapid succession. His progress was a continuous climb to one summit, followed by a dizzying swoop into the following depth.

Each climb was punctuated at the top by a gallon or so of water slopped into the dory from the crest of the wave. These influxes became so frequent that he was obliged to bail very often. Consequently he unshipped one oar and, crawling to the stern, shipped the other in the notch of the sternboard.

Here he sculled with one hand so as to keep the dory’s head to the wind, and bailed with the other. Being aft, his weight caused the water to run down to him, and he could thus perform the two operations at the same time.

When pitch-blackness had come he knew that he was out of reach of the schooner’s horn. His only chance lay in the fog’s lifting or the passing of some schooner.

His principal concern was for the wind. It was just the time of year for those “three-day” nor’-easters that harry the entire coast of North America. When the first excitement of his danger passed he was assailed by the fierce hunger of nervous and physical exhaustion, but there was no food aboard the dory. He had, of course, the breaker of water that was part of his regular equipment; but this was more for use during a long day of fishing than for the emergency of being lost at sea.

He took a hearty drink and prepared for the long watch of the night.

By a wax match several hours later he found that it was midnight. His struggle with wind and sea had now become unequal. He found it impractical to remain longer in the stern attempting to scull. So very cautiously he set about his last defensive measure.

Taking the two oars and the anchor, as well as the thwarts, he bound them together securely with the anchor roding. This drag he hove from the bow of the dory, and it swung the boat’s head into the wind. Schofield, with the bailer in one hand, lay flat in the bottom.

With the increasing sea, water splashed steadily over the sides so that his exertions never ceased. The chill of the night penetrated his soaked garments, and this, with his exhaustion, produced a stupor. The whistle of the wind and the hiss of foaming crests became dream sounds.

CHAPTER XII

OUT OF FREEKIRK HEAD

“OH, I wouldn’t think of such a thing for a minute!”

Captain Bijonah Turner waved his hand with an air of finality and favored his daughter with a glare meant to be pregnant with parental authority.

“But, father, listen to reason!” cried Nellie; “here is mother to take care of the three small children, and here am I with nothing whatever to do. Be sensible and let me go along. I certainly ought to be able to help in some way.”

“But,” expostulated the captain, “girls don’t go on fishing-trips.”

“Suppose the cook should fall sick or be hurt, then I would come in handy, wouldn’t I? But all this is not the real point. Things are different with us than they have ever been before; we have no home, and mother and the children have to board with Ma Sprague. If I stayed here I should be a burden, and I couldn’t stand that.”

Bijonah scratched his head and looked at the girl helplessly. He had yet to score his first victory over her in an argument.

“Have you asked your mother?” he queried at last, seeking his time-worn refuge.

“Yes,” said she, brightening at the imminence of victory, “and she says she thinks it will be just the thing.”

“All right,” said Bijonah weakly; “come along then. But mind, you’ll find things different. Your mother is boss of any land she puts her foot on, but once I get the Rosan past Swallowtail my word goes.”

“All right, daddy dear,” laughed the girl; “I know you’ll be just the finest captain I ever sailed with.” She kissed him impulsively and ran up-stairs to tell her mother the good news.

The departure of the fleet from Grande Mignon was a sad day in the history of the island.

The sun had hardly shown red and dripping from the sea when all the inhabitants were astir. Men from as far south as Seal Cove and Great Harbor clattered up the King’s Road in rickety vehicles, accompanied by their families and their dunnage.

In Freekirk Head alone less than ten men would be left ashore. Of these, one was Bill Boughton, the storekeeper, who was to arrange for the disposal of the catch; but the others were either incapacitated, sick, or old. The five aged fishermen, who subsisted on the charity of the town, formed a delegation on one stringpiece to wave the fleet farewell.

Altogether there were fifteen boats, ten schooners, and five sloops, carrying in all more than a hundred and twenty-five men. The whole resource of the island had been expended to provide tubs of bait and barrels of salt enough for all these, let alone the provisions.

The men either shipped on shares or, if they were fearful of chance, at a fixed monthly wage “and all found,” to be paid after the proceeds of the voyage were realized.

There was not a cent of Grande Mignon credit left in the world, and there was no child too small to realize that on the outcome of this venture hung the fate and future of the island.

It was a brilliant day, with a glorious blue sky overhead and a bracing breeze out of the east. Just beyond Long Island a low stratum of miasmic gray was the only shred of the usual fog to be seen on the whole horizon. In the little roadstead the vessels, black-hulled or white, rode eagerly and gracefully at their moorings, the bright sun bringing out the red, yellow, green, blue, and brown of the dories nested amidships.

At seven o’clock the steamer Grande Mignon blew a great blast of her whistle, cast off her lines, and cleared for St. Andrew’s and St. Stephens. Tooting a long, last salute, she rolled out into Fundy and out of sight around the point.

For these men breakfast was long past, but there were the myriad last details that could not be left undone; and it was fully eight o’clock before the last dory was swung aboard and the last barrel stowed.

Then there came the clicking of many windlasses and the strain of many ropes, and to the women and girls who lined the shore these noises were as the beatings of the executioner’s hand upon the cell-door of a condemned man.

For the first time they seemed to realize what was about to happen. The young girls and the brides wept, but those with children at their skirts looked stonily to the vessel that bore their loved ones; for they were hardened in the fear of death and bereavement, and had become fatalists.

The old women shook their heads, and if tears rolled down their faces they were the tears of dotage, and were shed perhaps for the swift and fleeting beauty of brides under the strain of their first long separation.

Of these last one stood apart, a shawl over her gray hair and her hands folded as though obedient to a will greater than her own. In all the color and pageant of departure May Schofield wondered where her son might be, the son whom she felt had run away from his just responsibilities. Two nights ago he had gone, and since that time the little cottage had seemed worse than deserted.

Somehow the story of the solicitor and his visit went swiftly around the village, and since that time Code’s mother had been the shrinking object of a host of polite but evidently pointed inquiries.

To most of these there was really no adequate reply, and the good woman had grown more hurt and more shrinking with every hour of the day. Now, with little orphan Josie at her side, she came out to see the departure of the fleet.

Suddenly there came the squeaking of blocks and the rattle and scrape of rings as foresails were rushed up at peak and throat. Headsails raced into position, and, with the anchors cat-headed; the vessels, with their captains at the wheels or tillers, swung into the wind and began to crawl ahead.

Behind them, as they forged toward the passage, lay the gray scimitar of stony beach half a mile long. Beyond it were the white, contented-looking cottages built along the road, and back of all rose the vivid green mountains, covered with pine, tamarack, and silver birch, above whose tops at the line of the summit there appeared three terrific, puffy thunder-heads.

As they moved toward Flag Point the gaily colored crowds moved with them past the post-office, the stores, the burned wharfs, and the fish stands.

Captain Bijonah Tanner, by right of seniority, led the way in the Rosan as commodore of the fleet. He stood to his tiller like a graven image, looking neither to right nor left, but gripping his pipe with all the strength of his remaining teeth.

He hoped that his triumph would not be lost upon his wife. Nor was it, for it was a month afterward before the neighbors ceased to hear how her Bige was the best captain that ever sailed out of Freekirk Head.

At Swallowtail Bijonah rounded the point, gave one majestic wave of his hat in farewell, and put the Rosan over on the starboard tack, for the course was southeast, and followed practically the wake of Code Schofield.

One after another the schooners and sloops, closely bunched, came about as smartly as their crews could bring them–and the smartest of them all was Nat Burns’s Nettie B.

Nellie Tanner, jealous for her father’s prestige, could not but admire the splendid discipline and tactics that whipped the Nettie about on the tack and sent her flying ahead of the Rosan like a great seabird. Once Swallowtail was passed the voyage had begun, and the lead belonged to any one who could take it.

At last the knifelike edge of Long Island shut them out completely, and seemed at the same instant to cut the last bonds and ties that had stretched from one to another as long as vision lasted. The men felt as released from a spell. One idea rushed into their minds suddenly and became an obsession.

Fish!

CHAPTER XIII

NAT BURNS SHOWS HIS HAND

OFF Cape Sable the fleet was overhauled by a half-dozen schooners bound the same way, which displayed American flags at their main trucks as they came up.

“Gloucestermen!” said Nat Burns at the wheel of the Nettie B. “Set balloon jib and stays’l and we’ll give ’em a try-out.”

The men jumped to the orders, and the Nettie gathered headway as the American schooners came up. But the Gloucester craft crept up, passed, and with an ironical dip of their little flags raced on to the Banks.

Cape Sable was not yet out of sight when a topmast on the Rosan broke off short in a sudden squall. Bijonah Tanner immediately laid her to and set all hands to work stepping his spare spar, as he would not think of returning to a shipyard. Nat Burns, when he noticed the accident, laid to in turn and announced his intention of standing by the Rosan until she was ready to go on.

As these were among the fastest vessels in the fleet, the others proceeded on their way, and Nat seized the opportunity of the repairs to pay his fiancée a visit and remain to supper on the Rosan.

He found Nellie radiant and more beautiful than he had ever seen her. Protected from the cool breeze by a frieze overcoat, she stood bareheaded by the forerigging, her cheeks red, her brown eyes bright like stars, and her soft brown hair blowing about her face in alluring wisps.

He took her in a strong embrace. She struggled free after a moment, her cheeks flooded with color.

“Don’t, Nat!” she cried. “Before all the men, too! Please behave yourself!”

This last a little nervously as she saw the gleam in his eyes. Suddenly (for her) all the day seemed to have lost its exhilaration. She was always glad to see Nat, but his insistent use of his fiancé rights under all circumstances grated on the natural delicacy that was hers.

His ardor dampened by this rebuke, the gleam in Nat’s eye became one of ugliness at his humiliation before the crew of the Rosan. He scowled furiously and stood by her side without saying a word. It was in this unfortunate moment that Nellie seized on the general topic of the day.

“Guess you’ll have to get off and push the Nettie B. before you can beat those Gloucestermen, Nat,” she said, teasing him.

“Say, I’ve heard about all I want to hear about that!” he snarled, suddenly losing control of himself as they walked back to the little cabin. The girl looked at him in hurt amazement. Never in all her life had a man spoken to her in such a tone. It was inconceivable that the man she was going to marry could address her so, if he even pretended to love her.

“Possibly you have,” she returned, not without a touch of asperity; “but you know as well as I do that you will have to deal with a Gloucester-built schooner before you are through with this voyage.”

In her efforts to placate him she had touched upon his sorest spot. His defeat by the American fishermen had been hard for his pride.

“I suppose you mean that crooked Schofield’s boat?” he flashed back, his face darkening.

“What do you mean by that?”

They were below now in her father’s little cabin, and she turned upon him with flashing eyes.

“Just what I said,” he returned sullenly.

“You say things then that have no foundation in fact,” she retorted vigorously. “You have no right to say a thing like that about Code Schofield.”

“I haven’t, eh?” he sneered, furious. “Since when have you been takin’ his side against me? No facts, eh? I’ll show him an’ you an’ everybody else whether there’s any foundation in fact! What do you suppose the insurance company is after him for if he isn’t a crook?”

Like all the people in Freekirk Head, Nellie had heard some of the rumors concerning Code’s possible part in the sinking of the May Schofield. Nat, for reasons of his own, had carefully refrained from enlarging on these to her, and in the absorption of her wooing by him she had let them go by unnoticed. Now, for the first time, the consequences they might have in Code’s life were made clear to her.

“I–I don’t know,” she faltered, unable to reply to his direct question. “But I know this, that all his life Code has been an honest man and one of my best friends. I grew up with him just as I did with you, and I resent such talk about him as much as I would if it were about you.”

“Yes,” he sneered, “he has been entirely too much of a good friend. What was he always over to your place for, I’d like to know? And, even after he knew we were engaged, what was he doin’ down at Ma Sprague’s that night I called? An’ what did you go to his place for after the fire when I tried to get you to come to mine?”

The last question he roared out at the top of his voice, and the girl, now afraid of him, shrank back against the wall of the cabin.

She knew it was useless to say that she and Code had been like brother and sister all their lives, and that May Schofield was a second mother to her. All reason was hopeless in the face of this unreasoning jealousy. After a moment she found her speech.

“I guess, Nat,” she said, “you had better go back to your schooner until you are in a different mood.”

“Afraid to answer, ain’t you?” he cried. “When I face you down you’re afraid to answer an’ tell me I’d better go away. Well, now let me tell you something. You’re entirely too friendly with that crook, an’ I won’t have it! You’re engaged to me, and what I say goes. An’ let me tell you something else.

“The insurance company is after him because he sunk the May Schofield on purpose. But that ain’t the worst of the things he did–”

“What do you mean?” she flashed at him.

“You’ll find out quick enough, and so will he,” he snarled. “I’m not saying what is goin’ to happen to him, but when I’m through we’ll see if your hero is such a fine specimen.”

From fear to anger her spirit had gone, and now under the lash it turned to cold disdain. With a swift motion of her right hand over her left she drew off the diamond ring he had given her and held it out to him.

“Take this, Nat,” she said, so coldly that for once his rage was checked. He looked stupidly at the glittering emblem of her love, and suddenly became aware of the extent to which he had driven her. The reaction was as swift as the rage.

“Please, Nellie dear,” he begged, “don’t do that! Take it back. Forgive me. Everything has piled up so to-day that I lost my temper. Please don’t do that!”

But he had gone too far. He had shown her a new side to his character.

“No, Nat,” she said calmly, but still with that icy inflection of disdain; “this has gone too far. Take this ring. Some time, when you have made amends for this afternoon, I may see you again.”

“I won’t take it,” he replied doggedly. “Please, Nellie, forgive–”

“Take it,” she flashed, “or I will throw it into the ocean!”

She had unconsciously submitted him to a final test. He was about to let her carry out her threat if she saw fit when his cupidity overcame him. He reached out his hand, and she dropped the ring into it. She stood silent, pale, and cold, waiting for him to go.

He moved away. He had reached the foot of the companionway when he turned back.

“He has brought me to this,” he said so slowly and evilly that each word seemed a drop of venom. “But I’ll make him pay. I’m goin’ to St. John’s, and when I get back it will be the sorriest day in his life and yours, too. His life won’t be worth the thread it hangs on!”

With that he went up the companionway and, not noticing the greeting of Captain Tanner, dropped into his yellow dory that swung and bumped against the Rosan’s side. Swiftly he rowed to the Nettie B. and clambered aboard, bellowing orders to get up sail. In fifteen minutes the schooner was on the back track under every stitch of canvas she carried.

Bijonah Tanner stared blankly after the retreating Nettie. Then, knowing that his daughter had been with Nat, dropped down into the little cabin.

He found Nellie seated in the chair by the little table, and weeping.

CHAPTER XIV

A DISCOVERY

Taken aback as he had been by the strange doings of Nat’s schooner, his dismay then was a feeble imitation of the panic that smote him now. It had long been a favorite formula of Bijonah’s that “A schooner’s a gal you can understand. She goes where ye send her, an’ ye know she’ll come back when ye tell her to. She’s a snug, trustin’ kind of critter, an’ she’s man’s best friend because she hain’t got a grain o’ sense. But woman!”

Here Bijonah always ended, his hands, his voice, and his sentence suspended in mid air.

Now he was baffled completely. Here was a girl who was deeply in love, crying. He tiptoed cautiously to the deck again and stole forward to the galley as though he had been detected in a suspicious action.

After a while the storm passed, and Nellie sat up, red-eyed and red-nosed, but with a measure of her usual tranquillity restored.

“Idiot!” she told herself. “To howl like that over him!”

Nellie finally regained her poise of mind and remembered that she had been at the point of writing a letter to her mother (to be mailed by the first vessel bound to a port) when Nat had interrupted her.

The table at which she sat was a rough, square one of oak, with one drawer that extended its whole width. She opened the drawer and found it stuffed with an untidy mass of paper, envelopes, newspapers, clippings, books, ink, and a mucilage-pot that had foundered in the last gale and spread its contents over everything.

Such was her struggle to find two clean sheets of paper and a pen that she finally dumped the contents of the drawer on top of the table and went to the task seriously. The very first thing that came under her hand was a heavy packet.

Turning it face up, she read, with surprise, a large feminine handwriting which said:

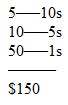

Mr. Code Schofield, kindness of Captain B. TannerLetter enclosedAt the right-hand side of the envelope was this:

Nellie Tanner stared at the envelope. It was the handwriting that held her. She had seen it before. She had once been honorary assistant treasurer of the Church of England chapel, and it suddenly came to her that this was the handwriting that had adorned Elsa Mallaby’s checks and subscriptions.