Полная версия:

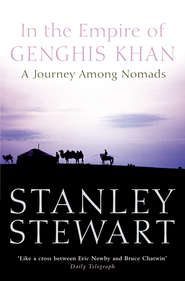

In the Empire of Genghis Khan: A Journey Among Nomads

Chapter Two THE VOYAGE OUT

At the docks my fellow passengers, a queue of burly figures beneath amorphous sacks, were making their up the gangway of the Mikhail Lomonosov like newsreel refugees.

Below in the cabin the resident onions had been cleared away leaving a faint astringent odour and a litter of red skins. The accommodation master appeared with my cabin-mate, a fifteen-year-old boy from Sevastopol. Kolya had been visiting his mother who was working in Istanbul. He was a thin boy with a mutinous complexion and an agitated manner. His gangly limbs jerked and rattled with adolescent impatience.

Kolya and I conversed in a bizarre amalgam of English, Turkish and Russian, prompted by various phrase books and a vocabulary of gestures and mime. It made for surprisingly lucid conversation. At first I tried to chat to him about kid’s stuff – his age, his school, his mother, ice-hockey – but he brushed these dull enquiries aside. He was keen to know the legal age limit for smoking and drinking in England, what kind of guns the police carried in London, and if the Queen was still in the business of beheading. His Istanbul had been somewhat different from mine. He had never heard of Haghia Sophia but he knew where to buy imitation Rolex watches and could quote the prices in three currencies. Like everyone else on this ship, he was a small trader, bringing home goods to sell in Sevastopol. He showed me his wares, – T-shirts, switchblades, pornographic magazines.

He sat on the edge of his bunk, drumming his legs in a nervous rhythm, blowing smoke rings towards the porthole. Kolya was in a hurry to grow up, to find the fast-track to the adult world of hard currency, illegal trading, and women. I was more than he could have hoped for as a cabin-mate, a representative of the glamorous and decadent West, that happy land of rap stars and Playstations. Hoping to cement our relationship, he looked for a way to make himself useful to me. I was a lone foreigner on a ship of Ukrainians and Russians, and he began to cast himself as my protector.

His mother appeared at the door of the cabin to say goodbye. A tall blonde Venus in a fur-collared coat, she was an exotic dancer making a Ukrainian fortune in one of Istanbul’s nightclubs. In the narrow passage Kolya was momentarily tearful – a boy like any other saying goodbye to his mother – but once she was gone he was quick to shake off this unwelcome vulnerability. He began to count the fistful of dollars that she had tucked into his pocket. Then he bolted out the door as if he had another ship to catch. Fifteen minutes later he was back, carrying a shopping bag from the free-port facilities on the quayside. Inside was a hard plastic case. Opening it, he lifted out an automatic pistol.

‘A hundred dollars,’ he said, breaking the seal on the box of ammunition.

‘What is it for?’ I asked, ducking as he swung the gun round the cabin.

‘Protection,’ the boy said. His eyes shone.

He had bought a shoulder-holster as well, and sought my help in buckling it round his thin shoulders. Then he slipped the gun into the new leather, and put on his jacket to hide the weapon. Smiling, the child stood before me, armed and dangerous, ready for the voyage home.

We sailed at nine. Below in the cabin, I felt a series of shudders run through the ship, and went out on deck to find us slipping away from our berth. Swinging about in the entrance to the Golden Horn, where a stream of cars was crossing the Galata Bridge, we turned up the Bosphorus away from the old city. The world’s most splendid skyline, that exquisite silhouette of minarets and domes, was darkening on a lemon-coloured sky. Haghia Sophia, round-shouldered above the trees of Gülhane, was the colour of a shell, a delicate shading of pinks and greys. Swaying in the wash of currents, ferries pushed out from the docks at Eminönü, bound for Üsküdar where the lights were coming on along the Asian shore. On the foredeck, I made my way through the cables and the piled crates to stand in the prow of the ship as we slipped northward through the heart of the city.

The austere face of the Dolmabahçe Palace, the nineteenth-century successor to the Topkapi, rose on our left. Its restrained façade belies a kitsch interior, a confection of operatic furnishings too ghastly to detail. It was here that the last Sultans watched their enfeebled empire slither to an ignominious end in the early years of the twentieth century. Much of the palace was given over to the harem, whose membership seemed to grow as the number of imperial provinces declined. Sex, presumably, was some consolation for political impotency.

The Bosphorus is a pilot’s nightmare. In the twisting straits ships veer back and forth between the two continents, dodging the powerful currents and each other. We passed so close to the mosque at Ortaköy on the European side that I was able to look down through grilled windows to see a row of neatly synchronized bottoms, upturned in prayer. Half a mile on I could see what was on television in the stylish rooms of the old renovated Ottoman houses on the Asian shore. Accidents are not uncommon, and people tell amusing anecdotes about residents of the waterside villas being awoken in the middle of a foggy winter night to find a Russian freighter parked in the living room. Since the late seventies no less than twelve listed yalis or Ottoman houses have been run down by ships, invariably captained by tipsy Russians.

A spring wind had blown up, the Kozkavuran Firtinasi, the Wind of the Roasting Walnuts, which comes down to the Bosphorus from the hills of Anatolia. On the Asian shore we passed the twin-spired façade of the Ottoman cavalry school where cadets were taught some shadow of the horsemanship that had brought their ancestors from Central Asia. Beyond I could make out the ragged outline of Rumeli Hisari, its crenellated walls breasting the European hills. On the slopes below is the oldest Turkish cemetery in Istanbul. Both here and at the cemetery at Eyüp, there is a marvellous literature of death, ironic and light-hearted. I had been reading translations of them at breakfast. They are a fine lesson in how to say farewell.

‘A pity to good-hearted Ismail Efendi,’ reads one epitaph, ‘whose death caused great sadness among his friends. Having caught the illness of love at the age of seventy, he took the bit between his teeth and dashed full gallop to paradise.’ On another tombstone a relief shows three trees, an almond, a cypress, and a peach; peaches are a Turkish metaphor for a woman’s breasts. ‘I’ve planted these trees so that people may know my fate. I loved an almond-eyed, cypress-tall maiden, and bade farewell to this world without savouring her peaches.’ As we passed, the cemetery showed only as an area of darkness.

Soon the city was slipping astern. The tiered lights fell away on both shores and Europe and Asia drifted apart as the straits widened. I stood in the bow until we passed Rumeli Feneri and Anadolu Feneri, the lighthouses on the two continents flanking the northern entrance to the Bosphorus, blinking with different rhythms.

In antiquity the Black Sea was a watery frontier. When the Ionian Greeks crossed its wind-driven reaches in search of fish and wheat, they came upon a people on the far shores who might have stepped from one of their own mythologies. The Scythians were a diverse collection of nomadic tribes with a passion for gold and horses. To the Greeks they were barbarians, the repository of their anxieties and their prejudice.

Herodotus gives us a compelling account of them. His descriptions show remarkable similarities with Friar William’s account of the Mongols two thousand years later, a reminder if one was needed of the static nature of nomadic society and the pervading anxieties they aroused in settled populations. They were a people without towns or crops, Herodotus tells us, clearly unnerved. They lived on the produce of their herds of cattle and sheep and horses, migrating seasonally in search of fresh pasture. They slaughtered their sheep without spilling blood, drank fermented mare’s milk and smoked hemp which made them howl with pleasure. They were shamans who worshipped the elements and the graves of their ancestors. In battle they formed battalions of mounted archers. Their equestrian skills were unrivalled, and they sought the trophies of their enemies’ skulls for drinking-cups.

The ship lifted on the sea’s swell, its bow rising to the dark void ahead. A new wind was blowing, the Meltemi. It was a north-easterly blowing from the Pontic steppe across 500 miles of sea. In Istanbul they say the Meltemi is a cleansing wind, dispelling foul airs and bad feelings.

Historically, the people of cities have had an ambivalent response to the unsettled landscapes of the steppe which seem to harbour ideas both of Arcadia and of chaos. Settled peoples were forever torn between the notions that nomads were barbarian monsters who threatened civilized order, and intuitive innocents who retained some elemental virtue that had been lost to them. ‘Nomads are closer to the created world of God,’ wrote the fourteenth-century Arab historian and philosopher, Ibn Khaldun, ‘and removed from the blameworthy customs that have infected the hearts of settlers.’ He believed that they alone could escape the cycles of decadence that infected all civilization. Only regular blasts of their cleansing winds allowed civilization to sustain its own virtues.

Kolya came to fetch me from my post in the ship’s bow, motioning for me to follow him as if he had something urgent to show me. Downstairs in our cabin he produced a bottle of champagne and four plastic cups. Then he disappeared and returned a moment later with two women.

Anna and Olga were the occupants of the neighbouring cabin. They were a dramatic illustration of the way that Slavic women seem unable to find any middle ground between slim grace and stout coarseness. Anna was a striking figure in tight jeans and a short sleeveless top. Olga, in cardigan and heavy shoes, wouldn’t have stood out among a party of dockers. Kolya, already a slave to female beauty, had only invited her to make up the numbers.

He was an energetic host, a fifteen-year-old playing at cocktail party. He poured the champagne, produced packets of American cigarettes and a bag of pistachio nuts, and chatted to everyone, the life of the party. I felt like a debutante being launched into the ship’s society. When the women asked about me Kolya explained I was going to visit the Tartars, and that I was a good friend of a priest called William who had been to visit them already.

Olga was silent and morose while Anna did all the talking. She had spent three weeks in Istanbul and was now travelling home to Sevastopol. The purpose of her visit was unclear. She tried to make it sound like a holiday but her cabin, like all the cabins on this boat, was so crowded with canvas sacks and cardboard boxes tied with string she could barely get the door open. The collapse of Communism had made everyone a salesman. But Anna, I suspected, had been trading more than tinned sardines. The Black Sea routes carried a heavy traffic of young women bound for the red-light districts of Istanbul. Many were part-timers making three or four trips a year to boost the family income.

We drank the champagne and when it was finished Kolya fetched another bottle, which I tried in vain to pay for. The boy was our host, magnanimous and expansive. He made toasts, he told dirty jokes that made the girls laugh, he kept his jacket on, buttoned up to conceal the gun. Olga soon drifted away to shift some crates and Anna now basked alone in our attention. She had become flirtatious. With the boy she already enjoyed a maternal familiarity, alternately hugging him and slapping him in mock remonstration, and now she extended the same attentions to me, pinching my shoulder and propping her elbows on my knees.

Kolya was showing off his collection of T-shirts adorned with American slogans. ‘California is a State of Mind’, one announced. ‘Better Dead than in Philadelphia’, another said. When he presented one to Anna, she leapt up to try it on. Standing with her back to us in the cramped cabin she removed her top. The boy gazed at her naked back and her bare breasts swelling into view as she stooped to pick up the T-shirt, then he shot a hot questioning glance at me. She swung round to model the gift. It seemed a trifle small. Her nipples pressed through the thin fabric just below a caption that read ‘Flying Fuck: the Mile High Club’.

When we had finished the second bottle Kolya took us off to the nightclub. I had not suspected the Lomonosov of harbouring a nightclub but Kolya was obviously a veteran clubber on the Black Sea routes. We descended a narrow stairway to a windowless dungeon in the bowels of the ship. Coloured lights in putrid hues of pink and blue glazed the shabby velvet sofas and plastic tables gathered round a small dance floor. The room smelt of stale beer and bilge water. Disco Muzak was leaking out of tinny speakers. Kolya ordered and paid for a round of drinks with umbrellas in them. I had given up trying to restrain him.

Throwing back her cocktails, Anna was now in full party mode. A tall bearded Russian, billed as Rasputin, had taken to the tiny stage with a synthesizer that replicated every instrument known to lounge lizards. She insisted I dance with her, tugging me by the arm out onto the empty dance floor. She had two basic steps, neither related to the music. The first was licentious: she ground her hips provocatively against me, insinuating one of her legs between mine. The other was a cross between the Moulin Rouge chorus line and a kung-fu exercise with a series of high kicks and spectacular twirls. It was a nerve-wracking business. The transition from simulated sex to the martial arts was so drunkenly abrupt that I was in real danger of having my head kicked in between romantic clinches.

All the following day at sea, Kolya followed me around the ship like a pint-sized bodyguard, his jacket bulging. Below in the cabin he spent most of his time loading and unloading the pistol. I tried to keep myself out of the line of fire.

In the dining hall Kolya, Anna and I ate together at a corner table. Meals on the Mikhail Lomonosov were dour occasions. Breakfast was an ancient sausage and a sweet cake. Lunch and dinner were indistinguishable – borscht, grey meat, potatoes, hard-boiled eggs. The passengers ate in silence, large pasty figures earnestly shovelling food in a room where the only sound was the awkward undertone of cutlery.

At breakfast we sat together like a dysfunctional family, bickering over cups of tea. We drifted into a curious relationship in which I was cast in the role of the grumpy and distracted pater. My failure to respond to Anna’s advances had upset them both. She behaved as if I was a shiftless husband who had humiliated her. In a filthy mood, Anna cut short the boy’s mediating advances by scolding him for his table manners, for his swearing, for his untucked shirt, for his lack of attention to her. Then she scolded me for not exercising more control over him. I retreated monosyllabically behind newspapers. It hardly seemed credible that we had met only twelve hours before. We chaffed at the confinement of our respective roles as if we had inhabited them for a lifetime.

Though he had conceived some loyalty to me as cabin-mate and foreigner, I was a disappointment to the boy. I knew nothing about rap stars, I lacked the flash accessories he associated with the West, and I took a firm and decidedly negative line about his chief pleasure of the moment: the revolver. With Anna he had a tempestuous and ambivalent relationship, alternately straining at her maternal leash and embracing her bursts of affection. Argument seemed to strengthen some perverse bond between them. When they made up, Kolya brought her bottles of Georgian champagne and fake Rolexes, then snuggled into her lap amid the sacks of cargo in her cabin in some uneasy limbo between a childish cuddle and a lover’s embrace.

He took the fact that I had not slept with Anna as a personal slight. When we were alone he would try to convince me that I should have sex with her. His pleas were both an injured innocence and a sordid knowledge beyond his years. At one moment he might have been the whining child of divorced parents, hoping for a reconciliation. At another, he was an underage pimp trying to drum up business.

In spite of Kolya’s disapproval of fraternizing with the staff, I had accepted an invitation from Dimitri, the second mate. He inhabited a small cabin on the port side of the ship where he had laid out afternoon tea: slabs of jellied meat, salted herrings, hard-boiled eggs, black bread, and glasses of vodka. Despite his long tenure on the Lomonosov the cabin had an anonymous air. There was a hold-all on the bed, two nylon shirts on hangers, and an officer’s jacket hanging on the back of the door. He might have been a passenger, uncharacteristically travelling light. His mood had not improved since the first evening I met him when the ship was docked in Istanbul.

‘In the Ukraine, in Russia, shipping has no future,’ he said, shaking his head. ‘There are no opportunities. When I first went to sea, the Soviet Union was a great naval power. Its ships sailed the world. It is unbelievable what has happened to us. You will see in Sevastopol. The great Black Sea Fleet. The naval docks look like a scrap yard.’

He poured the vodka and sank his teeth into a boiled egg.

‘Do you know what this ship was?’ he asked.

I shook my head. The eggs, like rubber, made speech difficult.

‘It was a research vessel,’ he said emphatically as if I might contradict him. ‘I have been seventeen years on this boat. Before 1990 we used to sail all over the world – the Indian Ocean, South America, Africa. We carried scientists – intelligent people, interesting people, engaged in important research. Professors from Leningrad, from Moscow, from Kiev. You cannot imagine the conversations in the dining room. Philosophy. Genetics. Hydrography. Meteorology. You couldn’t pass the door without learning something. And nice people.’ His voice softened at the memory of the nice professors. ‘Very nice people. Polite. People with manners.’

He crammed a salted herring between small rows of teeth. His expression seemed like an accusation of culpability, as if perhaps I was taking up space that might have been allocated to a wise professorial figure with interesting conversation and good table manners.

‘Look what has become of us. Carrying vegetables and what else back and forth across the Black Sea like a tramp boat. It is difficult to believe.’

I didn’t ask how this had happened. I knew he was going to tell me anyway.

‘Money,’ he exploded. ‘The country is bankrupt. Oh yes we all wanted freedom. We all wanted the end of Communism. But no one mentioned it would bankrupt the country. There is no money for research any more. There is no money for anything. So here we are.’

His rage subsided long enough for him to refill our glasses. ‘I have not been paid in five months,’ he said quietly.

I asked how he managed.

‘I have a kiosk, in Sevastopol.’ His voice had dropped; he was mumbling. He seemed ashamed of this descent into commerce as if it was not worthy of him, a ship’s officer. ‘We sell whisky and vodka, sweets, tobacco. I bring them from Turkey. Otherwise we would starve.’

In the Ukraine, as in the rest of the constituent parts of the old Union, the quest for a living has become everything. From education to the nuclear defence industry, all the great public institutions are obliged to hustle for things to sell like pensioners flogging the remnants of their attics on street corners in Moscow. For Dimitri any hope of advancement had shrunk with the maritime fleet. He had been second mate on the Lomonosov for the last twelve of his seventeen years of service, and still the first mate showed no signs of departure or death.

Economic pressures and the tedium of their endless passages had made the Mikhail Lomonosov a ship of malcontents, riven by jealousies and intrigues. The officers all hated one another. Dimitri hated the cargo master, the cargo master hated the chief engineer, the chief engineer hated the first mate, who hated him right back. Everyone hated the captain whose position allowed him access to the lucrative world of corruption.

Dimitri piled more sausage onto my plate. His anger had been spent, and he seemed apologetic about drawing me into his troubles, as if they were a family matter, unseemly to parade before a foreigner.

‘Do you know who Mikhail Lomonosov was?’ he asked.

I confessed I didn’t. I had seen his portrait hanging in the dining hall, an eighteenth-century figure in a powdered wig and a lace shirt.

‘You are not a Russian. How would you know? But the passengers on this ship. None of them know who Lomonosov was.’ He was beginning to grow agitated again, in spite of himself, chopping the air with his hand. ‘He was a great Russian, a scientist, a writer. He founded Moscow University. He set up the first laboratory in Russia. He was also a poet, a very great poet. He wrote about language and science and history. The scientists who travelled on the ship all knew his work. They discussed him. But these people, these traders, they are ignorant. They do not know their own history. They can tell you the price of every grade of vodka but they know nothing about Mikhail Lomonosov. No one cares about these things any more, about science, about poetry. Only about money, and prices in Istanbul.’

In the evening I went to visit him on the bridge during his watch. He was alone. The hushed solitude of the place and the instruments of his profession – charts, radar screens, compasses – had lightened his mood. On the chart table the Black Sea was neatly parcelled by lines of longitude and latitude. Near the bottom Istanbul straddled the Bosphorus. At the top Sevastopol was tucked carefully round a corner on the western shores of the Crimea. A thick smudged pencil line joined the two. Overdrawn countless times, it marked the single unvarying line to which his life had been reduced: 43° NE.

Below in the nightclub Rasputin was singing a Russian version of My Way. Despairing of me, Anna had transferred her attentions rather theatrically to the singer, and was now gyrating suggestively in front of the tiny stage. The purple lighting did Rasputin no favours. His eyes and cheeks were malevolent pockets of darkness.

I found Kolya alone at a corner table nursing a double brandy.

‘Anna seems to be enjoying herself,’ I said taking a seat.

He looked at me without speaking then turned his eyes back to the dance floor and the figure of Rasputin in its purple haze.

‘He is not exactly Sinatra,’ I said.

‘He is a shit,’ Kolya said.

The boy seemed to have diminished on his stool, sinking deeper into himself. He simmered with resentment. He felt Rasputin was displacing him in Anna’s affections, that the arbitrary tides of the adult world had shifted without any reference to him. He glowered at the singer from his corner table like a child gangster.

I retired and when Kolya arrived later in the cabin, he was sullen and uncommunicative. We played cards in a difficult silence. Half an hour later, Anna arrived with Rasputin, trailing all the forced merriment of the nightclub. She seemed to need to show off her acquisition to me and to Kolya in some act of petty revenge.

They sat together on the bunk opposite. Anna stroked his thigh. They chattered together in Ukrainian. The boy watched them coldly. Rasputin tried to draw him out with bantering exchanges. The nightclub had closed and the two were trying to press Kolya for his usual hospitality. Anna had delved into one of Kolya’s bags and produced a bottle of vodka which she proposed they drink. Rasputin held it up and made to open the screw top, looking teasingly to Kolya for his response. He was laughing open-mouthed, a barking ridicule emerging from between rows of long yellow teeth. Then he closed his mouth suddenly, and his expression changed. Anna and Rasputin were suddenly rigid.