Полная версия

Полная версияEssays: Scientific, Political, and Speculative, Volume I

Not only the directions, but also the velocities of rotation seem thus explicable. It might naturally be supposed that the large planets would revolve on their axes more slowly than the small ones: our terrestrial experiences of big and little bodies incline us to expect this. It is a corollary from the Nebular Hypothesis, however, more especially when interpreted as above, that while large planets will rotate rapidly, small ones will rotate slowly; and we find that in fact they do so. Other things equal, a concentrating nebulous mass which is diffused through a wide space, and whose outer parts have, therefore, to travel from great distances to the common centre of gravity, will acquire a high axial velocity in course of its aggregation; and conversely with a small mass. Still more marked will be the difference where the form of the genetic ring conspires to increase the rate of rotation. Other things equal, a genetic ring which is broadest in the direction of its plane will produce a mass rotating faster than one which is broadest at right angles to its plane; and if the ring is absolutely as well as relatively broad, the rotation will be very rapid. These conditions were, as we saw, fulfilled in the case of Jupiter; and Jupiter turns round his axis in less than ten hours. Saturn, in whose case, as above explained, the conditions were less favourable to rapid rotation, takes nearly ten hours and a half. While Mars, Earth, Venus, and Mercury, whose rings must have been slender, take more than double that time: the smallest taking the longest.

From the planets let us now pass to the satellites. Here, beyond the conspicuous facts commonly adverted to, that they go round their primaries in the directions in which these turn on their axes, in planes diverging but little from their equators, and in orbits nearly circular, there are several significant traits which must not be passed over.

One of them is that each set of satellites repeats in miniature the relations of the planets to the Sun, both in certain respects above named and in the order of their sizes. On progressing from the outside of the Solar System to its centre, we see that there are four large external planets, and four internal ones which are comparatively small. A like contrast holds between the outer and inner satellites in every case. Among the four satellites of Jupiter, the parallel is maintained as well as the comparative smallness of the number allows: the two outer ones are the largest, and the two inner ones the smallest. According to the most recent observations made by Mr. Lassell, the like is true of the four satellites of Uranus. In the case of Saturn, who has eight secondary planets revolving round him, the likeness is still more close in arrangement as in number: the three outer satellites are large, the inner ones small; and the contrasts of size are here much greater between the largest, which is nearly as big as Mars, and the smallest, which is with difficulty discovered even by the best telescopes. But the analogy does not end here. Just as with the planets, there is at first a general increase of size on travelling inwards from Neptune and Uranus, which do not differ very widely, to Saturn, which is much larger, and to Jupiter, which is the largest; so of the eight satellites of Saturn, the largest is not the outermost, but the outermost save two; so of Jupiter's four secondaries, the largest is the most remote but one. Now these parallelisms are inexplicable by the theory of final causes. For purposes of lighting, if this be the presumed object of these attendant bodies, it would have been far better had the larger been the nearer: at present, their remoteness renders them of less service than the smallest. To the Nebular Hypothesis, however, these analogies give further support. They show the action of a common physical cause. They imply a law of genesis, holding in the secondary systems as in the primary system.

Still more instructive shall we find the distribution of the satellites – their absence in some instances, and their presence in other instances, in smaller or greater numbers. The argument from design fails to account for this distribution. Supposing it be granted that planets nearer the Sun than ourselves, have no need of moons (though, considering that their nights are as dark, and, relatively to their brilliant days, even darker than ours, the need seems quite as great) – supposing this to be granted; how are we to explain the fact that Uranus has but half as many moons as Saturn, though he is at double the distance? While, however, the current presumption is untenable, the Nebular Hypothesis furnishes us with an explanation. It enables us to predict where satellites will be abundant and where they will be absent. The reasoning is as follows.

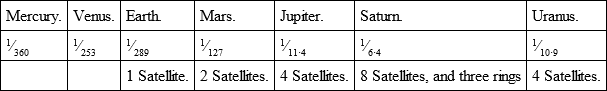

In a rotating nebulous spheroid which is concentrating into a planet, there are at work two antagonist mechanical tendencies – the centripetal and the centrifugal. While the force of gravitation draws all the atoms of the spheroid together, their tangential momentum is resolvable into two parts, of which one resists gravitation. The ratio which this centrifugal force bears to gravitation, varies, other things equal, as the square of the velocity. Hence, the aggregation of a rotating nebulous spheroid will be more or less hindered by this resisting force, according as the rate of rotation is high or low: the opposition, in equal spheroids, being four times as great when the rotation is twice as rapid; nine times as great when it is three times as rapid; and so on. Now the detachment of a ring from a planet-forming body of nebulous matter, implies that at its equatorial zone the increasing centrifugal force consequent on concentration has become so great as to balance gravity. Whence it is tolerably obvious that the detachment of rings will be most frequent from those masses in which the centrifugal tendency bears the greatest ratio to the gravitative tendency. Though it is not possible to calculate what ratio these two tendencies had to each other in the genetic spheroid which produced each planet, it is possible to calculate where each was the greatest and where the least. While it is true that the ratio which centrifugal force now bears to gravity at the equator of each planet, differs widely from that which it bore during the earlier stages of concentration; and while it is true that this change in the ratio, depending on the degree of contraction each planet has undergone, has in no two cases been the same; yet we may fairly conclude that where the ratio is still the greatest, it has been the greatest from the beginning. The satellite-forming tendency which each planet had, will be approximately indicated by the proportion now existing in it between the aggregating power, and the power that has opposed aggregation. On making the requisite calculations, a remarkable harmony with this inference comes out. The following table shows what fraction the centrifugal force is of the centripetal force in every case; and the relation which that fraction bears to the number of satellites.18

Thus taking as our standard of comparison the Earth with its one moon, we see that Mercury, in which the centrifugal force is relatively less, has no moon. Mars, in which it is relatively much greater, has two moons. Jupiter, in which it is far greater, has four moons. Uranus, in which it is greater still, has certainly four, and more if Herschel was right. Saturn, in which it is the greatest, being nearly one-sixth of gravity, has, including his rings, eleven attendants. The only instance in which there is nonconformity with observation, is that of Venus. Here it appears that the centrifugal force is relatively greater than in the Earth; and, according to the hypothesis, Venus ought to have a satellite. Respecting this anomaly several remarks are to be made. Without putting any faith in the alleged discovery of a satellite of Venus (repeated at intervals by five different observers), it may yet be contended that as the satellites of Mars eluded observation up to 1877, a satellite of Venus may have eluded observation up to the present time. Merely naming this as possible, but not probable, a consideration of more weight is that the period of rotation of Venus is but indefinitely fixed, and that a small diminution in the estimated angular velocity of her equator would bring the result into congruity with the hypothesis. Further, it may be remarked that not exact, but only general, congruity is to be expected; since the process of condensation of each planet from nebulous matter can scarcely be expected to have gone on with absolute uniformity: the angular velocities of the superposed strata of nebulous matter probably differed from one another in degrees unlike in each case; and such differences would affect the satellite-forming tendency. But without making much of these possible explanations of the discrepancy, the correspondence between inference and fact which we find in so many planets, may be held to afford strong support to the Nebular Hypothesis.

Certain more special peculiarities of the satellites must be mentioned as suggestive. One of them is the relation between the period of revolution and that of rotation. No discoverable purpose is served by making the Moon go round its axis in the same time that it goes round the Earth: for our convenience, a more rapid axial motion would have been equally good; and for any possible inhabitants of the Moon, much better. Against the alternative supposition, that the equality occurred by accident, the probabilities are, as Laplace says, infinity to one. But to this arrangement, which is explicable neither as the result of design nor of chance, the Nebular Hypothesis furnishes a clue. In his Exposition du Système du Monde, Laplace shows, by reasoning too detailed to be here repeated, that under the circumstances such a relation of movements would be likely to establish itself.

Among Jupiter's satellites, which severally display these same synchronous movements, there also exists a still more remarkable relation. "If the mean angular velocity of the first satellite be added to twice that of the third, the sum will be equal to three times that of the second;" and "from this it results that the situations of any two of them being given, that of the third can be found." Now here, as before, no conceivable advantage results. Neither in this case can the connexion have been accidental: the probabilities are infinity to one to the contrary. But again, according to Laplace, the Nebular Hypothesis supplies a solution. Are not these significant facts?

Most significant fact of all, however, is that presented by the rings of Saturn. As Laplace remarks, they are, as it were, still extant witnesses of the genetic process he propounded. Here we have, continuing permanently, forms of aggregation like those through which each planet and satellite once passed; and their movements are just what, in conformity with the hypothesis, they should be. "La durée de la rotation d'une planète doit donc être, d'après cette hypothèse, plus petite que la durée de la révolution du corps le plus voisin qui circule autour d'elle," says Laplace. And he then points out that the time of Saturn's rotation is to that of his rings as 427 to 438 – an amount of difference such as was to be expected.19

Respecting Saturn's rings it may be further remarked that the place of their occurrence is not without significance.

Rings detached early in the process of concentration, consisting of gaseous matter having extremely little power of cohesion, can have little ability to resist the disruptive forces due to imperfect balance; and, therefore, collapse into satellites. A ring of a denser kind, whether solid, liquid, or composed of small discrete masses (as Saturn's rings are now concluded to be), we can expect will be formed only near the body of a planet when it has reached so late a stage of concentration that its equatorial portions contain matters capable of easy precipitation into liquid and, finally, solid forms. Even then it can be produced only under special conditions. Gaining a rapidly-increasing preponderance as the gravitative force does during the closing stages of concentration, the centrifugal force cannot, in ordinary cases, cause the leaving behind of rings when the mass has become dense. Only where the centrifugal force has all along been very great, and remains powerful to the last, as in Saturn, can we expect dense rings to be formed.

We find, then, that besides those most conspicuous peculiarities of the Solar System which first suggested the theory of its evolution, there are many minor ones pointing in the same direction. Were there no other evidence, these mechanical arrangements would, considered in their totality, go far to establish the Nebular Hypothesis.

From the mechanical arrangements of the Solar System, turn we now to its physical characters; and, first, let us consider the inferences deducible from relative specific gravities.

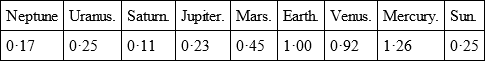

The fact that, speaking generally, the denser planets are the nearer to the Sun, has been by some considered as adding another to the many indications of nebular origin. Legitimately assuming that the outermost parts of a rotating nebulous spheroid, in its earlier stages of concentration, must be comparatively rare; and that the increasing density which the whole mass acquires as it contracts, must hold of the outermost parts as well as the rest; it is argued that the rings successively detached will be more and more dense, and will form planets of higher and higher specific gravities. But passing over other objections, this explanation is quite inadequate to account for the facts. Using the Earth as a standard of comparison, the relative densities run thus: —

Two insurmountable objections are presented by this series. The first is, that the progression is but a broken one. Neptune is denser than Saturn, which, by the hypothesis, it ought not to be. Uranus is denser than Jupiter, which it ought not to be. Uranus is denser than Saturn, and the Earth is denser than Venus – facts which not only give no countenance to, but directly contradict, the alleged explanation. The second objection, still more manifestly fatal, is the low specific gravity of the Sun. If, when the matter of the Sun filled the orbit of Mercury, its state of aggregation was such that the detached ring formed a planet having a specific gravity equal to that of iron; then the Sun itself, now that it has concentrated, should have a specific gravity much greater than that of iron; whereas its specific gravity is only half as much again as that of water. Instead of being far denser than the nearest planet, it is but one-fifth as dense.

While these anomalies render untenable the position that the relative specific gravities of the planets are direct indications of nebular condensation; it by no means follows that they negative it. Several causes may be assigned for these unlikenesses: – 1. Differences among the planets in respect of the elementary substances composing them; or in the proportions of such elementary substances, if they contain the same kinds. 2. Differences among them in respect of the quantities of matter they contain; for, other things equal, the mutual gravitation of molecules will make a larger mass denser than a smaller. 3. Differences of temperatures; for, other things equal, those having higher temperatures will have lower specific gravities. 4. Differences of physical states, as being gaseous, liquid, or solid; or, otherwise, differences in the relative amounts of the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter they contain.

It is quite possible, and we may indeed say probable, that all these causes come into play, and that they take various shares in the production of the several results. But difficulties stand in the way of definite conclusions. Nevertheless, if we revert to the hypothesis of nebular genesis, we are furnished with partial explanations if nothing more.

In the cooling of celestial bodies several factors are concerned. The first and simplest is the one illustrated at every fire-side by the rapid blackening of little cinders which fall into the ashes, in contrast with the long-continued redness of big lumps. This factor is the relation between increase of surface and increase of content: surfaces, in similar bodies, increasing as the squares of the dimensions while contents increase as their cubes. Hence, on comparing the Earth with Jupiter, whose diameter is about eleven times that of the Earth, it results that while his surface is 125 times as great, his content is 1390 times as great. Now even (supposing we assume like temperatures and like densities) if the only effect were that through a given area of surface eleven times more matter had to be cooled in the one case than in the other, there would be a vast difference between the times occupied in concentration. But, in virtue of a second factor, the difference would be much greater than that consequent on these geometrical relations. The escape of heat from a cooling mass is effected by conduction, or by convection, or by both. In a solid it is wholly by conduction; in a liquid or gas the chief part is played by convection – by circulating currents which continually transpose the hotter and cooler parts. Now in fluid spheroids – gaseous, or liquid, or mixed – increasing size entails an increasing obstacle to cooling, consequent on the increasing distances to be travelled by the circulating currents. Of course the relation is not a simple one: the velocities of the currents will be unlike. It is manifest, however, that in a sphere of eleven times the diameter, the transit of matter from centre to surface and back from surface to centre, will take a much longer time; even if its movement is unrestrained. But its movement is, in such cases as we are considering, greatly restrained. In a rotating spheroid there come into play retarding forces augmenting with the velocity of rotation. In such a spheroid the respective portions of matter (supposing them equal in their angular velocities round the axis, which they will tend more and more to become as the density increases), must vary in their absolute velocities according to their distances from the axis; and each portion cannot have its distance from the axis changed by circulating currents, which it must continually be, without loss or gain in its quantity of motion: through the medium of fluid friction, force must be expended, now in increasing its motion and now in retarding its motion. Hence, when the larger spheroid has also a higher velocity of rotation, the relative slowness of the circulating currents, and the consequent retardation of cooling, must be much greater than is implied by the extra distances to be travelled.

And now observe the correspondence between inference and fact. In the first place, if we compare the group of the great planets, Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus, with the group of the small planets, Mars, Earth, Venus, and Mercury, we see that low density goes along with great size and great velocity of rotation, and that high density goes along with small size and small velocity of rotation. In the second place, we are shown this relation still more clearly if we compare the extreme instances – Saturn and Mercury. The special contrast of these two, like the general contrast of the groups, points to the truth that low density, like the satellite-forming tendency, is associated with the ratio borne by centrifugal force to gravity; for in the case of Saturn with his many satellites and least density, centrifugal force at the equator is nearly 1⁄6th of gravity, whereas in Mercury with no satellite and greatest density centrifugal force is but 1⁄360th of gravity.

There are, however, certain factors which, working in an opposite way, qualify and complicate these effects. Other things equal, mutual gravitation among the parts of a large mass will cause a greater evolution of heat than is similarly caused in a small mass; and the resulting difference of temperature will tend to produce more rapid dissipation of heat. To this must be added the greater velocity of the circulating currents which the intenser forces at work in larger spheroids will produce – a contrast made still greater by the relatively smaller retardation by friction to which the more voluminous currents are exposed. In these causes, joined with causes previously indicated, we may recognize a probable explanation of the otherwise anomalous fact that the Sun, though having a thousand times the mass of Jupiter, has yet reached as advanced a stage of concentration. For the force of gravity in the Sun, which at his surface is some ten times that at the surface of Jupiter, must expose his central parts to a pressure relatively very intense; producing, during contraction, a relatively rapid genesis of heat. And it is further to be remarked that, though the circulating currents in the Sun have far greater distances to travel, yet since his rotation is relatively so slow that the angular velocity of his substance is but about one-sixtieth of that of Jupiter's substance, the resulting obstacle to circulating currents is relatively small, and the escape of heat far less retarded. Here, too, we may note that in the co-operation of these factors, there seems a reason for the greater concentration reached by Jupiter than by Saturn, though Saturn is the elder as well as the smaller of the two; for at the same time that the gravitative force in Jupiter is more than twice as great as in Saturn, his velocity of rotation is very little greater, so that the opposition of the centrifugal force to the centripetal is not much more than half.

But now, not judging more than roughly of the effects of these several factors, co-operating in various ways and degrees, some to aid concentration and others to resist it, it is sufficiently manifest that, other things equal, the larger nebulous spheroids, longer in losing their heat, will more slowly reach high specific gravities; and that where the contrasts in size are so immense as those between the greater and the smaller planets, the smaller may have reached relatively high specific gravities when the greater have reached but relatively low ones. Further, it appears that such qualification of the process as results from the more rapid genesis of heat in the larger masses, will be countervailed where high velocity of rotation greatly impedes the circulating currents. Thus interpreted then, the various specific gravities of the planets may be held to furnish further evidences supporting the Nebular Hypothesis.

Increase of density and escape of heat are correlated phenomena, and hence in the foregoing section, treating of the respective densities of the celestial bodies in connexion with nebular condensation, much has been said and implied respecting the accompanying genesis and dissipation of heat. Quite apart, however, from the foregoing arguments and inferences, there is to be noted the fact that in the present temperatures of the celestial bodies at large we find additional supports to the hypothesis; and these, too, of the most substantial character. For if, as is implied above, heat must inevitably be generated by the aggregation of diffused matter, we ought to find in all the heavenly bodies, either present high temperatures or marks of past high temperatures. This we do, in the places and in the degrees which the hypothesis requires.

Observations showing that as we descend below the Earth's surface there is a progressive increase of heat, joined with the conspicuous evidence furnished by volcanoes, necessitate the conclusion that the temperature is very high at great depths. Whether, as some believe, the interior of the Earth is still molten, or whether, as Sir William Thomson contends, it must be solid; there is agreement in the inference that its heat is intense. And it has been further shown that the rate at which the temperature increases on descending below the surface, is such as would be found in a mass which had been cooling for an indefinite period. The Moon, too, shows us, by its corrugations and its conspicuous extinct volcanoes, that in it there has been a process of refrigeration and contraction, like that which has gone on in the Earth. There is no teleological explanation of these facts. The frequent destructions of life by earthquakes and volcanoes, imply, rather, that it would have been better had the Earth been created with a low internal temperature. But if we contemplate the facts in connexion with the Nebular Hypothesis, we see that this still-continued high internal heat is one of its corollaries. The Earth must have passed through the gaseous and the molten conditions before it became solid, and must for an almost infinite period by its internal heat continue to bear evidence of this origin.