Полная версия:

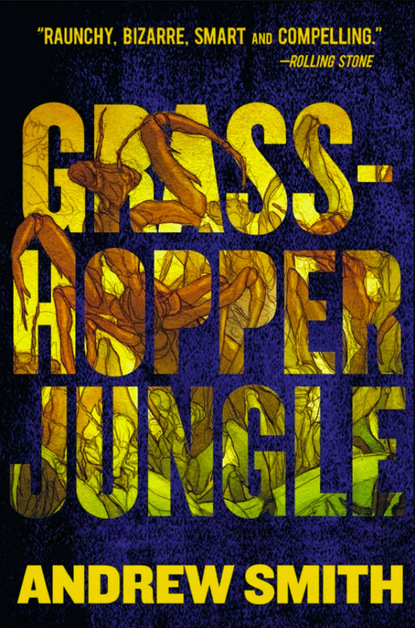

Grasshopper Jungle

As history is my judge, probably not.

“I think we should go up on the roof and get our shit back. Tonight, when no one will see us. Those were my best shoes.”

Actually, those were Robby’s only non-Lutheran-boy school shoes.

I was willing.

“I bet there’s some cool shit up on that roof,” I said.

“Oh yeah. No doubt everyone in Ealing hides their cool shit up on the roof of The Pancake House.”

“Or maybe not.”

WHAT MADE THIS COUNTRY GREAT

ROBBY HAD AN older sister named Sheila.

Sheila was married and lived with her husband and Robby’s six-year-old nephew in Cedar Falls.

I had a brother named Eric.

Eric was in Afghanistan, shooting at people and shit like that.

As bad as Cedar Falls is, even the Del Vista Arms for that matter, Eric could have gone somewhere better than Afghanistan.

Both our moms took little blue pills to make them feel not so anxious. My mom took them because of Eric, and Robby’s mom needed pills because when we were in seventh grade, Robby’s dad left and didn’t come back. My dad was a history teacher at Curtis Crane Lutheran Academy, and my mom was a bookkeeper at the Hy-Vee, so we had a house and a dog, and shit like that.

Hy-Vee sells groceries and shit.

My parents were predictable and ominous. They also weren’t home yet when Robby and I got there in our still-wet socks and T-shirts.

“Watch out for dog shit,” I said as we walked across the yard.

“Austin, you should mow your lawn.”

“Then it would make the dog shit too easy to see and my dad would tell me to pick it up. So I’d have to mow the lawn and pick up dog shit.”

“It’s thinking like that that made this country great,” Robby said. “You know, if they ever gave a Nobel Prize for avoiding work, every year some white guy in Iowa would get a million bucks and a trip to Sweden.”

Thinking about me and Robby going to Sweden made me horny.

SHANN’S NEW OLD HOUSE

FIRST THING, NATURALLY: We got food from the kitchen.

We also made dirt tracks on the floor because socks are notoriously effective when it comes to redistributing filth from sidewalks, lawns, the Del Vista Arms, and Robby’s untidy old Ford Explorer.

I boiled water, and we took Cups-O-Noodles and Doritos into my room.

Robby sat on my bed and ate, waiting patiently while I recorded the last little bit of the day’s history in my notebook.

“Here.” I tossed my cell phone over to the bed. “Call Shann.”

“Have you ever smelled a Dorito ?”

“Mmmm . . .” I had to think about it. I wrote. “Probably not.”

“Just checking,” he said, “’Cause they smell like my nephew’s feet.”

“Why did you smell a six-year-old kid’s feet?”

“Good question.”

As usual, Shann got mad because I had Robby call her using my phone, and when she answered, she thought it was me. This, quite naturally, made me horny. But Robby explained to her I was writing, and he told her that something terrible had happened to us. He asked if it would be okay that we came over to her new old house as soon as we finished eating.

Robby was such a suave communicator when it came to relaying messages to Shann. In fact, I believed it was the biggest component of why she was so much in love with me. Sometimes, I wished I could cut off Robby’s head and attach it to my body, but there were more than a couple things wrong with that idea: First, uncomfortably enough, it kind of made me horny to think about a hybridized Robby/Austin having sex with Shann; and, second, decapitation was a sensitive topic in Ealing.

Well, anywhere, really. But, in Ealing during the late 1960s there was this weird string of serial murders that went unsolved. And they all involved headlessness.

History is full of decapitations, and Iowa is no exception.

So, after we finished eating, I outfitted Robby with some clean socks, a Titus Andronicus T-shirt (I changed into an Animal Collective shirt—all my tees are bands), and gave him my nicest pair of Adidas.

And both of us tried to pretend we didn’t notice my dad’s truck pulling up the drive just as we took off for Shann’s.

“Perfect timing,” I said.

Robby answered by pushing in the dashboard cigarette lighter.

Besides all the head-cutting-off shit that went on fifty years ago, Ealing was also known for Dr. Grady McKeon, founder of McKeon Industries, which, up until about six months ago, employed over half the town’s labor force. Grady McKeon was some kind of scientist, and he made a fortune from defense programs during the Cold War. When the fight against Communism went south on McKeon, the factory retooled and started manufacturing sonic-pulse shower-heads and toothbrushes, which ultimately became far more profitable when made in Malaysia or somewhere like that. So the factory shut down, and that’s also why most of the Ealing strip mall was deserted, and why every time I visited Robby at the Del Vista Arms, there were more and more Pay or Quit notices hanging on doors.

And that’s a half century of an Iowa town’s history in four sentences.

Grady McKeon was gone, but his much younger brother still lived and ran businesses in Ealing. Johnny McKeon owned Tipsy Cricket Liquors and the From Attic to Seller thrift store, both of which were big crowd-pleasers at the strip mall.

Johnny, who was responsible for thinking up the names of those two establishments entirely on his own, was also Shann’s stepfather.

And Shannon Collins, whom Robby and I called Shann, her mother (the relatively brand-new Mrs. McKeon), and Johnny had just taken ownership of the McKeon House, a decrepit old wooden monstrosity that was on the registry of historic homes in Ealing.

Well, actually, it was the only historic home in Ealing.

It took Robby and me two cigarettes to get to Shann’s new old house.

It had already been a rough day.

We were going to need another pack.

GOING SOMEWHERE YOU SHOULDN’T GO

SHANNON KISSED ME on the lips at the door of her new old house.

She kissed Robby on the lips, too.

Shann always kissed Robby on the mouth after she kissed me.

It made me horny.

I wondered what she would say if I asked her to have a threesome with us in her new old, unfurnished bedroom.

I knew what Robby would say.

Duh.

I wondered if it made me homosexual to even think about having a threesome with Robby and Shann. And I hated knowing that it would be easier for me to ask Robby to do it than to ask my own girlfriend.

I felt myself turning red and starting to sweat uncomfortably in my Animal Collective shirt.

And I realized that for a good three and a half minutes, I stood there at the doorway to a big empty house that smelled like old people’s skin, thinking about three-ways involving my friends.

So I wondered if that meant I was gay.

I hadn’t been listening to anything Shann and Robby were talking about, and while I was pondering my sexuality, they were probably thinking about how I was an idiot.

I might just as well have been a blowup doll.

These are the things I don’t write down in the history books, but probably should.

I don’t think any historians ever wrote shit like that.

“You have to excuse him. He got kneed in the balls.”

“Huh?”

Robby nudged me with his shoulder and said it again, louder, because idiots always understand English when you yell it at them: “YOU HAVE TO EXCUSE HIM. HE GOT KNEED IN THE BALLS.”

Shann put her hand flat on the side of my face, the way that real moms, who don’t take lots of drugs every day, do to little boys they think might be sick. Real moms have sensors or some kind of shit like that in their hands.

Shann’s mom, Mrs. McKeon, was a real mom. She also used to be a nurse, before she married Johnny McKeon.

“Are you okay, Austin?”

“Huh? Yeah. Oh. I’m sorry, Shann. I was kind of tripping out about something.”

Having a three-way in Sweden with Robby and her was what I was tripping out about.

But I didn’t tell her.

Shann’s room was empty.

The entire house was mostly empty, so our footsteps and voices echoed like sound effects in horror films about three kids who are going somewhere they shouldn’t go.

Thinking about things like that definitely did not make me horny.

In fact, just about the only things I noticed in that musty mausoleum of a house were unopened boxes—brand-new ones—containing McKeon Pulse-O-Matic® showerheads and toothbrushes.

“The moving van’s going to be here this afternoon. They just finished at the house,” Shann explained as the three of us stood awkwardly in her empty, echoey room.

Because, in an empty bedroom with creaky old wood floors, it is a natural human response to just stand there and shift your weight from foot to foot, and think about sex.

ROBBY’S VOLCANO

SHANN AND I started going out with each other in seventh grade.

When I think about it, a lot of stuff happened to us that year.

There are nine filled, double-sided-paged volumes of Austin Szerba’s Unexpurgated History of Ealing, Iowa for that year alone.

That year, Eric went into the Marines and left me at home, brotherless, with our dog named Ingrid, a rusty golden retriever with a real dynamo of an excretory tract.

People in Ealing use expressions like real dynamo whenever something moves fast-er than a growing stalk of corn.

It was also the same year Robby’s dad went to Guatemala to film a documentary about a volcanic eruption. Lots of stuff erupted that year, because Mr. Brees met a woman, got her pregnant, and expatriated to Guatemala.

And, just like a lot of boys in seventh grade, I started erupting quite frequently then, too.

A real dynamo.

And, that year Shannon Collins’s mom moved to Ealing, enrolled her daughter at Curtis Crane Lutheran Academy (where we were all good, non-smoking, non-erupting Christians), and married Johnny McKeon, the owner of From Attic to Seller Consignment Store and Tipsy Cricket Liquors.

And I fell in love with Shann Collins.

It was a very confusing time. I didn’t realize then, in seventh grade as I was, that the time, and the eruptions, and everything else that happened to me would only keep getting more and more confusing through grades 8, 9, and 10.

I will tell you how it was I managed to get Shann Collins to fall in love with me, too: My best friend, Robby Brees, taught me how to dance.

I was infatuated with Shann from the moment I saw her. But, being the new kid at school, and new in Ealing, Shann kept pretty much to herself, especially when it came to such things as eruptive, real dynamo, horny thirteen-year-old boys.

Robby noticed how deeply smitten I was by Shann, so he selflessly taught me how to dance, just in time for the Curtis Crane Lutheran Academy End-of-Year Mixed-Gender Mixer . Normally, genders were not something that were permitted to mix at Curtis Crane Lutheran Academy.

So I went over to Robby’s apartment every night for two and a half weeks, and we played vinyl records in his room and he taught me how to dance. This was just after Robby and his mother had to move out of their house and into the Del Vista Arms.

Robby was always the best dancer of any guy I ever knew, and girls like Shann love boys who can dance.

History does show that boys who dance are far more likely to pass along their genes than boys who don’t.

Boys who dance are genetic volcanoes.

It made me feel confused, though, dancing alone with Robby in his bedroom, because it was kind of, well, fun and exceptional, in the same way that smoking cigarettes made me feel horny.

Seventh grade was also when Robby and I stole a pack of cigarettes from Robby’s mom. By the time we got into tenth grade, Robby’s mom started buying them for us. She might take drugs and not have one of those sensor things in the palm of her hand like real moms do, but Mrs. Brees doesn’t mind when teenage boys smoke cigarettes in her house and dance with each other, alone in the bedroom, and that’s saying something.

That year, at the end of seventh grade, Robby confessed that he’d rather dance with me than with any girl. He didn’t just mean dance . It was very confusing to me. It made me wonder more about myself, whom I doubted, than about Robby, whom I suppose I love.

At first, I thought Robby would grow out of it—you know, start erupting like everyone else.

But there was nothing wrong with Robby’s volcano, and he never did grow out of it.

So it was at the Curtis Crane Lutheran Academy End-of-Year Mixed-Gender Mixer that Robby casually and bravely walked up to the new girl, Shann Collins, and announced to her:

“My friend Austin Szerba is shy. That’s him over there. He is good-looking, don’t you think? He’s also a nice guy, he writes poetry, he’s a really fantastic dancer. He would like very much if you would agree to dance with him.”

And everything, confusing as it was, worked out beautifully for me and Shann and Robby after that.

DOORS THAT GO SOMEWHERE; DOORS THAT GO NOWHERE

“OKAY. SO, BASICALLY this house is, like, infested with demons or something,” Shann told us.

Demonic infestations have a way of making guys feel not so horny.

“It’s in the Ealing Registry of Historical Homes,” I pointed out.

“People died here.”

“You should get that kind of air freshener shit that you plug into outlets so it masks the scent of death and decay with springtime potpourri,” Robby offered.

“Look at this,” she said. “There are doors that go nowhere, and I swear I heard something ticking and rattling inside my wall a moment ago.”

Shann used words like moment .

She wasn’t from Ealing.

One of the walls in her creaky room had two doors set into it. The wall itself was kind of creepy. It had wallpaper with flowers that seemed to float like stemless clones between wide red stripes. If I pictured a room where I was going to murder someone, aside from the instruments of torture and shit like that, it would have this wallpaper. If I was on death row, awaiting electrocution, I’d be wearing pajamas with the same pattern on them.

Shann went to the door on the left and pulled it open.

When she opened it, there was only the jamb and frame of the door, and then a wall of bricks behind it.

“See?”

I could only imagine what was on the other side of the bricks.

Robby, naturally, felt compelled to say something less than comforting.

“I suggest you don’t liberate whatever’s imprisoned back there,” he said.

Shann was getting angry. I knew I should intervene, but I didn’t know what to say.

“Nowadays, people spend a lot of money for distressed bricks like those,” I said.

It was probably for the best that Shann wasn’t paying attention to me.

“And look at this,” she said.

When she opened the second door, a long, narrow stairway extended down into darkness on the other side. The chasm was at least twenty feet deep, but it dead-ended at another distressed brick wall, and there were no other doorways leading off in any direction that I could see.

“What can you expect from a house this old?” I asked.

It was a good question.

Ghosts and shit like that, was what I was thinking, though. You wouldn’t expect miniature ponies and trained talking peacocks that dispensed Sugar Babies and gumballs from their asses, would you?

“I don’t want to stay in this room by myself,” Shann said.

And that made me very horny again.

I also wanted candy.

Shann, obviously stressed, looked at Robby, then at me.

“I need to talk to you, Austin,” she said, and motioned for me to go with her down the candyless staircase of death and decay.

Robby took the hint. “Uh. I need to go to the bathroom. Maybe Pulse-O-Matic® my teeth. Or take a shower. Or something.”

He made a tentative, weight-shifting creak onto one leg and I followed Shann behind door number two.

We sat beside each other on the staircase.

Our bare legs touched.

Shann had a perfect body, a Friday-after-school body that was mostly visible because she was barefoot, and wore tight, cuffed shorts with a cantaloupe-colored halter top. A boy could go insane, I thought, just being this close to Shann’s uncovered shoulders, wheat hair, and heavy breasts.

This staircase to nothing was a fitting dungeon for constantly erupting, real-dynamo sixteen-year-old boys like me.

“Why is Robby wearing your clothes, and what happened to you and him?”

While we sat there, three important things struck me about Shann: First, I realized that, like most girls I knew, Shann could ask questions in machine-gun bursts that peppered the male brain with entirely unrelated projectiles of interrogation. Second, it was often unstated, but clear by her tone, that Shann was jealous of Robby, possibly to the point of being a little curious about my sexuality. I know, maybe that was also my confusion, as well. Because, third, what was most troubling to me, was that despite all the fantasies, all the intricately structured if/then scenarios I concocted involving Shann Collins and me, whenever an opportunity to take action presented itself—like being alone with her in a nearly sealed dungeon—I became timid and restrained.

I couldn’t understand it at all.

History chews up sexually uncertain boys, and spits us out as recycled, generic greeting cards for lonely old men.

Dr. Grady McKeon was a lonely old man. I can only conclude he must have also at one time been a sexually confused, unexplainably horny teenage boy who erupted all over everything at the least opportune times. He was twenty-five years old, and well on his way to building an empire of profits when his younger brother, Johnny, was born. I once heard a tobacco-chewing hog farmer say that, in Iowa, folks liked to spread out their children like dog shit on a dance floor.

Dr. Grady McKeon would be Shann’s stepuncle, if there is such a thing, and if he weren’t dead. He was the last person to live in the historic McKeon house. He died when his private jet went down in the Gulf of Mexico. Its engines choked to death on ash from Mount Huacamochtli, the same erupting volcano in Guatemala that Robert Brees Sr. was filming a documentary on. And it also happened the same year Robby Brees and I smoked our first cigarette, danced together, and I fell in love with Shannon Collins.

Johnny McKeon never wanted to live in his dead brother’s old house. It took Shann’s mother about four years of badgering to get him to finally break down and take the place out of mothballs.

I held Shann’s hand, and we sat there in the dungeon with our legs pressed together, and I was so frustrated I felt like I could explode. But I concentrated, and methodically went through the entire account of what happened to me and Robby at Grasshopper Jungle. I told her about our plan to climb up onto the roof of the Ealing Mall to get our stuff back.

“I’m coming with you,” she decided.

“Not up on the roof,” I said, so authoritatively my voice lowered an octave.

Sounding father-like to Shann in the echoing darkness of the staircase that led nowhere made me feel horny, demons or not. I scooted closer and put my arm around her so that my fingers relaxed and splayed across the little swath of exposed skin above the waist of her shorts.

“I’ll wait in Robby’s car. I’ll be your lookout.”

“Shann?” I said.

I almost had myself convinced to ask her if didn’t she think it was time we had sex, and the thought made me feel dizzy. I would force myself to no longer have any doubt or confusion, to not wind up recycled by history.

“What?”

“This staircase really is creepy.”

And just as I pushed her firmly against the distressed brick wall and put my open mouth over hers, Robby swung the door wide above us and said, “The moving van’s here.”

CURFEW

WHILE SHANN’S MOM, the movers, and Johnny McKeon worked at unloading and organizing the houseful of furniture they’d shipped over from their old-but-much-newer house, the three of us stole away in Robby’s Ford Explorer on our mission to reclaim our shoes and skateboards.

Friday nights in Ealing, Iowa, rarely got more thrilling than climbing up on the roof of a three-quarters abandoned mall, and we were up for the excitement.

On Fridays, my curfew came at midnight, which meant that if I was quiet enough I could stay out until just before my mother served breakfast on Saturday morning.

I had to check in with my dad and mom, so they’d know I was still alive.

I told them I was going out for pizza with Robby and Shann.

It wasn’t a lie; it was an abbreviation.

I was not concerned about going to hell.

Nobody who was born and raised in Ealing, Iowa, was afraid of hell, or Afghanistan, or living at the Del Vista Arms.

Checking in for Robby meant swinging by his two-bedroom deluxe apartment at the Del Vista Arms and asking his mom for five dollars and a fresh pack of cigarettes, while Shann and I waited in the parking lot.

Shann did not smoke.

She was smarter than Robby and me, but she didn’t complain about our habit.

STUPID PEOPLE SHOULD NEVER READ BOOKS

IT TOOK ME a very long time to work up the nerve to kiss Shann Collins, who was the first and only girl I had ever kissed.

There was a possibility that I’d never have kissed her, too, because she was the one who actually initiated the kiss.

It happened nearly one full year after the Curtis Crane Lutheran Academy End-of-Year Mixed-Gender Mixer.

Like Robby explained to her: I was shy.

I was on the conveyor belt toward the paper shredder of history with countless scores of other sexually confused boys.

After the Curtis Crane Lutheran Academy End-of-Year Mixed-Gender Mixer, I tried to get Shann to pay more serious attention to me.

I tried any reasonable method I could think of. I joined the archery club when I found out she was a member, and I offered multiple times to do homework with her. Sadly, nothing seemed to result in serious progress.

At last, all I could do was let Shann Collins know that I would be there for her if she ever needed a friend or a favor. I do not believe I had any ulterior motives in telling her such a thing. Well, to be honest, I probably did.

I’d leave notes for Shann tucked inside her schoolbooks; I would compliment her on her outfit. She laughed at such things. Shann knew it was a ridiculous thing to write, since all the girls at Curtis Crane Lutheran Academy dressed exactly the same way. Still, history will show that patient boys with a sense of humor, who can also dance, tend to have more opportunities to participate in the evolution of the species than boys who give up and mope quietly on the sidelines.

But I began to worry. Rumors were spreading around Curtis Crane Lutheran Academy about me and Robby, even though I never heard anything directly.