Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

Life of Napoleon Bonaparte. Volume IV

Napoleon blames all the world for his reverses. When he has no longer any one to blame, he accuses his destiny. But it is himself only whom he should blame; and the more so, because the very desertion on the part of his allies, which hastened his fall, could have had no other cause but the deep wounds he had inflicted by his despotic pride, and his acts of injustice. He was himself the original author of his misfortunes, by outraging those who had contributed to his elevation. It was his own hands that consummated his ruin; he was, in all the strictness of the term, a political suicide, and so much the more guilty, that he did not dispose of himself alone, but of France at the same time.

No. IIEXTRACT FROM MANUSCRIPT OBSERVATIONS ON NAPOLEON'S RUSSIAN CAMPAIGN, BY AN ENGLISH OFFICER OF RANK[See p. 135.]Having examined into the probabilities of Ségur's allegation, that Buonaparte entertained thoughts of taking up his winter-quarters at Witepsk, the military commentator proceeds as follows: —

"The Russian army at Smolensk, seeing the manner in which the French army was dispersed in cantonments between the rivers Dwina and Dneister, moved, on the 7th of August, towards Rudnei, in order to beat up their quarters. They succeeded in surprising those of Sebastiani, and did him a good deal of mischief in an attack upon Jukowo. In the meantime, Barclay de Tolly was alarmed by a movement made by the Viceroy about Souraj, on the Dwina; and he countermanded the original plan of operations, with a view to extend his right flank; and for some days afterwards, the Russian army made various false movements, and was in a considerable degree of confusion. Whether Napoleon's plan was founded upon the march of the Russian army from Smolensk, as supposed by Ségur; or upon their position at Smolensk, in the first days of August, he carried it into execution, notwithstanding that march.

"Accordingly, he broke up his cantonments upon the Dwina on the 10th of August, and marched his army by different columns by corps across the front of the Russian army, from these cantonments to Rassassna, upon the Dnieper. The false movements made by the Russian army from the 7th to the 12th of August, prevented their obtaining early knowledge of this march, and they were not in a situation to be able to take advantage of it. On the other hand, Napoleon could have had no knowledge of the miscalculated movements made by the Russian army.

"Being arrived at Rassassna, where he was joined by Davoust, with three divisions of the first corps, he crossed the Dnieper on the 14th. The corps of Poniatowski and Junot were at the same time moving upon Smolensk direct from Mohilow.

"Napoleon moved forward upon Smolensk.

"The garrison of that place, a division of infantry under General Newerofskoi, had come out as far as Krasnoi, to observe the movements of the French troops on the left of the Dnieper, supposed to be advancing along the Dnieper from Orcha. Murat attacked this body of troops with all his cavalry; but they made good their retreat to Smolensk, although repeatedly charged in their retreat. These charges were of little avail, however; and this operation affords another instance of the security with which good infantry can stand the attack of cavalry. This division of about 6000 infantry had no artificial defence, excepting two rows of trees on each side of the road, of which they certainly availed themselves. But the use made even of this defence shows how small an obstacle will impede and check the operations of the cavalry.

"It would probably have been more advisable if Murat, knowing of the movement of Poniatowski and Junot directed from Mohilow upon Smolensk, had not pushed this body of troops too hard. They must have been induced to delay on their retreat, in order effectually to reconnoitre their enemy. The fort would undoubtedly in that case have fallen into the hands of Poniatowski.

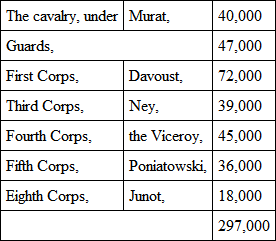

"On the 17th of August, Napoleon assembled the whole of the operating army before Smolensk, on the left of the Dnieper. It consisted as follows: —

"These corps had, about six weeks before, entered the country with the numbers above stated; they had had no military affair to occasion loss; yet Ségur says, they were now reckoned at 185,000. The returns of the 3d August are stated to have given the last numbers only.

"The town had been attacked on the 16th, first, by a battalion – secondly, by a division of the third corps – which troops were repulsed. In the mean time, Bagration moved upon Katani, upon the Dnieper, having heard of Napoleon's movement from the Dwina; and Barclay de Tolly having authorised the resumption of the plan of operations in pursuance of which the Russian army had broken up from Smolensk on the 17th. He moved thence on the 16th, along the right of the Dnieper, back upon Smolensk, and immediately reinforced the garrison. He was followed that night by Barclay de Tolly, who relieved the troops under the command of Bagration, which were in the town: and the whole Russian army was collected at Smolensk, on the right of the Dnieper.

"Bagration moved during the same night with his army on the road to Moscow. Barclay remained in support of the troops in Smolensk.

"Napoleon, after waiting till two o'clock, in expectation that Barclay would cross the Dnieper, and move out of Smolensk, to fight a general battle, attacked the town on the 17th, with his whole army, and was repulsed with loss; and in the evening the Russian troops recovered possession of all the outposts. Barclay, however, withdrew the garrison in the night of the 17th, and destroyed the bridges of communication between the French and the town. The enemy crossed the Dnieper by fords, and obtained for a moment possession of the faubourg called Petersburg, on the right of that river, but were driven back. The Russian army, after remaining all day on the right of the river opposite Smolensk, retired on the night of the 18th; and the French that night repaired the bridges on the Dnieper.

"Before I proceed farther with the narrative, it is necessary to consider a little this movement of Napoleon, which is greatly admired by all the writers on the subject.

"When this movement was undertaken, the communication of the army was necessarily removed altogether from the Dwina. Instead of proceeding from Wilna upon Witepsk, it proceeded from Wilna upon Minsk, where a great magazine was formed, and thence across the Beresina, upon Orcha on the Dnieper, and thence upon Smolensk. The consequences of this alteration will appear presently, when we come to consider of the retreat.

"It is obvious, that the position of the great magazine at Minsk threw the communications of the army necessarily upon the Beresina, and eventually within the influence of the operations of the Russian armies from the southward. Napoleon's objects by the movement might have been three: First, to force the Russians to a general battle; secondly, to obtain possession of Smolensk, without the loss or the delay of a siege; thirdly, to endeavour again to obtain a position in rear of the Russian army, upon their communications with Moscow, and with the southern provinces of the Russian empire. This movement is much admired, and extolled by the Russian as well as the French writers upon this war; yet if it is tried by the only tests of any military movement – its objects compared with its risks and difficulties, and its success compared with the same risks and difficulties, and with the probable hazards and the probably successful result of other movements to attain the same objects – it will be found to have failed completely.

"The risk has been stated to consist, first, in the march of the different corps from their cantonments, on the Dwina, to Rassassna, on the Dnieper, across the front of the Russian army, without the protection of a body of troops formed for that purpose; and, next, in the hazard incurred in removing the communication of the army from Witepsk to Minsk. This will be discussed presently.

"In respect of the first object – that of bringing the Russian army to a general battle – it must be obvious to every body, that the fort of Smolensk and the Dnieper river were between Napoleon and the Russian army when his movement was completed. Although, therefore, the armies were not only in sight, but within musket-shot of each other, it was impossible for Napoleon to bring the enemy to an action on that ground without his consent; and as the ground would not have been advantageous to the Russian army, and an unsuccessful, or even a doubtful result, could not have saved Smolensk, and there was no object sufficiently important to induce the Russian general to incur the risk of an unsuccessful result of a general action, it was not very probable he would move into the trap which Ségur describes as laid for him.

"Neither was it likely that Napoleon would take Smolensk by any assault which this movement might enable him to make upon that place. He had no heavy artillery, and he tried in vain to take the place by storm, first, by a battalion, then, by a division, and lastly, by the whole army. He obtained possession of Smolensk at last, only because the Russian general had made no previous arrangements for occupying the place; and because Barclay knew that, if he left a garrison there unprovided, it must fall into Napoleon's hands a few days sooner or later. The Russian general then thought proper to evacuate the place; and notwithstanding the position of Napoleon on the left of the Dnieper, and his attempts to take the place by storm, the Russian general would have kept the possession, if he could have either maintained the position of his own army in the neighbourhood, or could have supplied the place adequately before he retired from it.

"The possession of the place depended, then, on the position of the Russian army; and what follows will show, that other measures and movements than those adopted were better calculated to dislodge the Russian army from Smolensk.

"There can be no doubt that, upon Napoleon's arrival at Smolensk, he had gained six marches upon his enemy. If Napoleon, when he crossed the Dnieper at Rassassna, had masked Smolensk, and marched direct upon any point of the Dnieper above that place, he could have posted himself with his whole army upon the communications of his enemy with Moscow; and his enemy could scarcely have attempted to pass across his front, to seek the road by Kalouga. Barclay must have gone to the northward, evacuating or leaving Smolensk to its fate, and Napoleon might have continued his march upon Moscow, keeping his position constantly between his enemy and his communications with that city, and with the southern provinces. The fate of Smolensk could not have been doubtful.

"Here, then, a different mode, even upon the same plan of manœuvring, would have produced two of the three objects which Napoleon is supposed to have had in view by these movements. But these were not the only movements in his power at that time. The Viceroy is stated to have been at Souraj and Velij. If, instead of moving by his right, Napoleon had moved by his left, and brought the first, fifth, and eighth corps from the Dneiper to form the reserve; and had marched from Souraj upon any point of the Upper Dnieper, he would equally have put himself in the rear of his enemy, and in a position to act upon his communications. He would have effected this object with greater certainty, if he had ventured to move the first, and the fifth and eighth corps through the country on the left of the Dnieper. And in this last movement there would have been no great risk – first, because Napoleon's manœuvres upon the Dwina would have attracted all the enemy's attention; secondly, because these corps would have all passed Smolensk, before the Russian generals could have known of their movement, in like manner as Napoleon passed the Dnieper and arrived at Smolensk without their knowledge. By either of these modes of proceeding, Napoleon would have cut off his enemy from their communications, would have obliged them to fight a battle to resign these communications, and in all probability Smolensk would have fallen into his hands without loss, with its buildings entire – an object of the last consequence in the event of the campaign.

"Either of these last modes of effecting the object would have been shorter by two marches than the movement of the whole army upon Rassassna."

END OF VOLUME FOURTH1

See Russian proclamation to the inhabitants of Finland, Feb. 18, 1808 Annual Register, vol. l., p. 301.

2

Annual Register, vol. l., p. 759.

3

Mémoires de Fouché, tom. i., p. 337.

4

In 1798, Bernadotte married Eugénie Cléry, the daughter of a considerable merchant at Marseilles, and sister to Julia, the wife of Joseph Buonaparte.

5

"It was not Bernadotte whom Cambêcérès and the Duke of Feltre requested to undertake the defence of Antwerp; but it was I who received several couriers on this subject, and who in fact took the command of the combined army, sufficiently in time to prevent the English surprising Antwerp, as they already had done Walcheren. It was I who flooded the borders of the Scheldt, and erected batteries there. Bernadotte arrived a fortnight afterwards; and, in pursuance of the orders of Napoleon and Clarke, which were officially communicated to me, I resigned the command to him." – Louis Buonaparte, p. 60.

6

See Papers relating to the expedition to the Scheldt, Parliamentary Debates, vol. xv., Appendix; and Annual Register, vol. l., pp. 543, 546, 559.

7

See Declaration of the Pope against the usurpations of Napoleon, dated May 19, 1808; Annual Register, vol. l., p. 314.

8

"Napoleon was of Italian origin, but he was born a Frenchman. It is difficult to comprehend for what purpose are those continual repetitions of his Italian origin. His partiality for Italy was natural enough, since he had conquered it, and this beautiful peninsula was a trophy of the national glory, of which Sir Walter Scott allows Napoleon to have been very jealous. I nevertheless doubt whether he had the intention of uniting Italy, and making Rome its capital. Many of my brother's actions contradict the supposition. I was near him one day when he received the report of some victories in Spain, and amongst others, of one in which the Italian troops had greatly distinguished themselves. One of the persons who were with him exclaimed, at this news – that the Italians would show themselves worthy of obtaining their independence, and it was to be desired that the whole of Italy should be united into one national body. 'Heaven forbid it!' exclaimed Napoleon, with involuntary emotion, 'they would soon be masters of the Gauls.' Amongst all the calumnies heaped against him, there are none more unjust than those which attack his patriotism: he was essentially French, indeed, too exclusively so; for all excess is bad." – Louis Buonaparte, p. 62.

9

"With regard to the removal of the monuments of antiquity, and to the works undertaken by my brother for their preservation, they were not merely projected; they were not only begun, but even far advanced, and many of them finished." – Louis Buonaparte, p. 63.

10

Published, May 17, at Vienna, and proclaimed in all the public squares, markets, &c., of that capital.

11

Annual Register, vol. li., p. 513; Botta, tom. iv., p. 394.

12

Botta, tom. iv., p. 395; Jomini, tom. iii., p. 242; Savary, tom. ii., part ii., p. 140.

13

See Las Cases, vol. ii., pp. 12 and 13. He avowed that he himself would have refused, as a man and an officer, to mount guard on the Pope, "whose transportation into France," he added, "was done without my authority." Observing the surprise of Las Cases, he added, "that what he said was very true, together with other things which he would learn by and by. Besides," he proceeded, "you are to distinguish the deeds of a sovereign, who acts collectively, as different from those of an individual, who is restrained by no consideration that prevents him from following his own sentiments. Policy often permits, nay orders, a prince to do that which would be unpardonable in an individual." Of this denial and this apology, we shall only say, that the first seems very apocryphal, and the second would justify any crime which Machiavel or Achitophel could invent or recommend. Murat is the person whom the favourers of Napoleon are desirous to load with the violence committed on the Pope. But if Murat had dared to take so much upon himself, would it not have been as king of Naples? and by what warrant could he have transferred the Pontiff from place to place in the north of Italy, and even in France itself, the Emperor's dominions, and not his own? Besides, if Napoleon was, as has been stated, surprised, shocked, and incensed at the captivity of the Pope, why did he not instantly restore him to his liberty, with suitable apologies, and indemnification? His not doing so plainly shows, that if Murat and Radet had not express orders for what they did, they at least knew well it would be agreeable to the Emperor when done, and his acquiescence in their violence is a sufficient proof that they argued justly. – S.

"The Emperor knew nothing of the event until it had occurred; and then it was too late to disown it. He approved of what had been done, established the Pope at Savona, and afterwards united Rome to the French empire, thereby annulling the donation made of it by Charlemagne. This annexation was regretted by all, because every one desired peace." – Savary, tom. ii., part ii., p. 142

14

"In the eyes of Europe, Pius VII. was considered as an illustrious and affecting victim of greedy ambition. A prisoner at Savona, he was despoiled of all his external honours, and shut out from all communication with the cardinals, as well as deprived of all means of issuing bulls and assembling a council. What food for the petite église, for the turbulence of some priests, and for the hatred of some devotees! I immediately saw all these leavens would reproduce the secret associations we had with so much difficulty suppressed. In fact, Napoleon, by undoing all that he had hitherto done to calm and conciliate the minds of the people, disposed them in the end to withdraw themselves from his power, and even to ally themselves to his enemies, as soon as they had the courage to show themselves in force." – Fouché, tom. i., p. 335.

15

The assassin of Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, in 1628.

16

The political fanatic of Jena, who assassinated Kotzebue at Manheim, in 1819.

17

"In the midst of the Emperor's occupations at Vienna, he was not unmindful of the memory of the Chevalier Bayard. The chapel of the village of Martinière, in which that hero had been christened, was repaired at great expense by his orders. He also directed that the heart of the chevalier should be removed to the said chapel with due ceremony; and an inscription, dictated by the Emperor himself, recording the praises of the knight 'without fear and without reproach,' was placed on the leaden box containing his heart." – Savary, tom. ii., part ii., p. 97.

18

Las Cases, tom. ii., p. 12; Savary, tom. ii., part ii., p. 151; Rapp, p. 141.

19

"The wretched young man was taken to Vienna, brought before a council of war, and executed on the 27th. He had taken no sustenance since the 24th, because, as he said, he had sufficient strength to walk to the place of execution. His last words were – 'Liberty forever! Germany for ever! Death to the tyrant!' I delivered the report to Napoleon, who desired me to keep the knife that had been found upon the criminal. It is still in my possession." – Rapp, p. 147.

20

Las Cases, tom. ii., p. 104.

21

For a copy of the treaty, see Annual Register, vol. li., p. 791.

22

Annual Register, vol. li., p. 790.

23

The verses are well known, —

24

"'A son by Josephine would have completed my happiness. It would have put an end to her jealousy, by which I was continually harassed. She despaired of having a child, and she in consequence looked forward with dread to the future.'" – Napoleon, Las Cases, tom. ii., p. 298.

25

Fouché, tom. i., p. 324.

26

"Never did I see Napoleon a prey to deeper and more concentrated grief; never did I see Josephine in more agonizing affliction. They appeared to find in it a mournful presentiment of a futurity without happiness and without hope." – Fouché, tom. i., p. 324.

27

"It would ill have become me to have kept within my own breast the suggestions of my foresight. In a confidential memoir, which I read to Napoleon himself, I represented to him the necessity of dissolving his marriage; of immediately forming, as Emperor, a new alliance more suitable and more happy; and of giving an heir to the throne on which Providence had placed him. Without declaring any thing positive, Napoleon let me perceive, that, in a political point of view, the dissolution of his marriage was already determined in his mind." – Fouché, tom. i., p. 326.

28

Fouché, tom. i., p. 328.

29

Mémoires de Fouché, tom. i., p. 348.

30

"By the permission of our dear and august consort, I ought to declare, that not perceiving any hope of having children, which may fulfil the wants of his policy and the interests of France, I am pleased to give him the greatest proof of attachment and devotion which has ever been given on earth. I possess all from his bounty; it was his hand which crowned me; and from the height of this throne I have received nothing but proofs of affection and love from the French people. I think I prove myself grateful in consenting to the dissolution of a marriage which heretofore was an obstacle to the welfare of France, which deprived it of the happiness of being one day governed by the descendant of a great man, evidently raised up by Providence, to efface the evils of a terrible revolution, and to re-establish the altar, the throne, and social order. But the dissolution of my marriage will in no degree change the sentiments of my heart; the Emperor will ever have in me his best friend. I know how much this act, demanded by policy, and by interest so great, has chilled his heart; but both of us exult in the sacrifice which we make for the good of the country." —Moniteur, Dec. 17, 1809; Annual Register, vol. li., p. 808.

31

"In quitting the court, Josephine drew the hearts of all its votaries after her: she was endeared to all by a kindness of disposition which was without a parallel. She never did the smallest injury to any one in the days of her power: her very enemies found in her a protectress: not a day of her life but what she asked a favour for some person, oftentimes unknown to her, but whom she found to be deserving of her protection. Regardless of self, her whole time was engaged in attending to the wants of others." – Savary, tom. ii., part ii., p. 177.

32

Maria Louisa, the eldest daughter of the Emperor of Austria and Maria Theresa of Naples, was born the 12th December, 1791. Her stature was sufficiently majestic, her complexion fresh and blooming, her eyes blue and animated, her hair light, and her hand and foot so beautiful, that they might have served as models for the sculptor.

33

Fouché, tom. i., p. 350.

34

"She had always been given to understand that Berthier, who had married her by proxy at Vienna, in person and age exactly resembled the Emperor: she, however, signified that she observed a very pleasing difference between them." – Las Cases, tom. i., p. 312.